Abstract

Palliative care is a multidisciplinary approach to symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in treatment decision-making for patients with serious illness and their families. It emphasizes well-being at any point along the disease trajectory, regardless of prognosis. The term “palliative care” is often incorrectly used as a synonym for end-of-life care, or “hospice care”. However, palliative care does not require a terminal diagnosis or proximity to death, a misconception that we will address in this article. Multiple randomized clinical trials demonstrate the many benefits of early integration of palliative care for patients with cancer, including reductions in symptom burden, improvements in quality-of-life, mood, and overall survival, as well as improved caregiver outcomes. Thus, early concurrent palliative care integrated with cancer-directed care has emerged as a standard-of-care practice for patients with cancer. However, patients with hematologic malignancies rarely utilize palliative care services, despite their many unmet palliative care needs, and are much less likely to use palliative care compared to patients with solid tumors. In this article, we will define “palliative care” and address some common misconceptions regarding its role as part of high-quality care for patients with cancer. We will then review the evidence supporting the integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer care, discuss perceived barriers to palliative care in hematologic malignancies, and suggest opportunities and triggers for earlier and more frequent palliative care referral in this population.

Learning Objectives

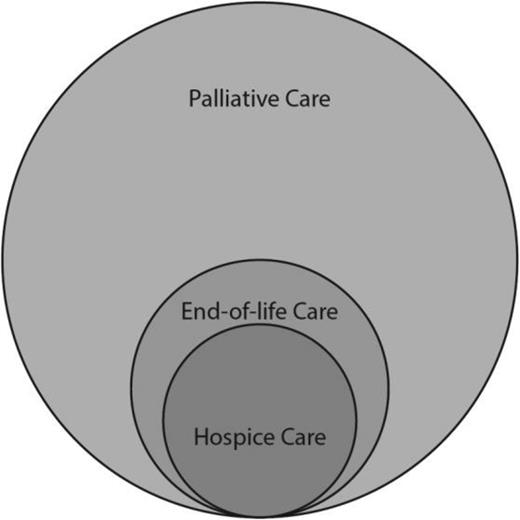

Describe the differences between “palliative care,” “hospice care,” and “end-of-life care”

List the major benefits of early palliative care as reported in the major randomized trials done to date

Recognize specific scenarios and indications that warrant specialist palliative care consultation for patients with hematologic malignancies

Palliative care is specialized medical care for people facing a serious illness,1 like a hematologic malignancy. The term “palliative care” is sometimes incorrectly used as a synonym for end-of-life care, or “hospice care”; however, palliative care requires neither a terminal diagnosis nor proximity to death; a misconception that we will address in the first section of this article. Rather, a growing body of evidence highlights that patients with cancer derive many benefits from palliative care including reductions in symptom burden,2 improvements in quality-of-life and mood,3,4 improved survival,4,5 as well as improved caregiver outcomes6 ; this is true even for those receiving active cancer treatment. However, patients with hematologic malignancies are much less likely to access palliative care services than patients with solid tumors,7,8 despite growing evidence of many unmet palliative care needs in this population.9 This discrepancy suggests a need for more education about palliative care in the hematology community, and more efforts to adapt palliative care services to better meet the needs of patients with hematologic malignancies.8,10 This article will present a contemporary definition of “palliative care”, review the evidence supporting the integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer care, discuss perceived barriers to palliative care in hematologic malignancies, and suggest opportunities and triggers for earlier and more frequent palliative care referral in this population.

What is “palliative care”?

The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) defines “palliative care” as follows:

“Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses. It focuses on providing patients with relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve quality-of-life for the patient and the family.”1

Palliative care is a multidisciplinary approach to symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in treatment decision-making for patients with serious illness and their families. It emphasizes the well-being of patients and families at any point along their disease trajectory, regardless of their illness state. “Palliative care” therefore does not refer to a particular place or a specific stage of illness, but rather it describes a philosophy of care. This type of care can be provided across a variety of settings, by different types of clinicians and professionals. This philosophy is embodied in the second portion of the CAPC definition of palliative care, which states the following:

“Palliative care is provided by a specially-trained team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work together with a patient's other doctors to provide an extra layer of support. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided along with curative treatment.”1

Similarly, the World Health Organization defines palliative care as follows:

“…an approach that improves the quality-of-life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”11

These definitions are contrary to the medical vernacular, wherein the term “palliative care” is often used specifically (and incorrectly) to describe late-stage, terminal care, such as that provided by “hospice” agencies. More accurately, the term “palliative care” encompasses much more than just end-of-life or hospice care, as illustrated in Figure 1. Although hospice care is one type of palliative care, and is indeed also the most common type of end-of-life care provided in the United States, this figure demonstrates that not all palliative care is hospice care. Instead, palliative care is an essential component of serious illness care, much farther upstream from the terminal phase. Therefore, palliative care should be viewed as a necessary component of care for patients with cancer from the time of diagnosis. This notion was popularized in the “inverted triangles model” of palliative care, as shown in Figure 2. Herein, palliative care begins at diagnosis, and increases in “dosage” or focus as needed throughout the continuum of illness. This idea is also embodied in the American Society of Clinical Oncology's Provisional Clinical Opinion statement as published in 2012, which states that all patients with metastatic cancer, or with refractory symptoms, should have access to concurrent palliative care services as part of their comprehensive cancer care.12 Similarly, the American College of Surgeons' Commission on Cancer now requires the availability of palliative care services as a condition of their accreditation of comprehensive cancer centers.13 The hematologic malignancies world is arguably several steps behind in achieving this level of integration.

The workforce

With increasing evidence of its many benefits, the palliative care workforce continues to grow. In 2000, less than one-quarter of US hospitals with 50 or more beds had a palliative care team; in 2012 >60% of similarly-sized hospitals had a team, and this number is forecasted to reach 80% in 2015.14 To date, 85% of large (>300 bed) hospitals have a palliative care team.15 With the expansion of the palliative care workforce, there has also been an increase in its legitimacy. In 2006, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized “hospice and palliative medicine” as an official medical subspecialty. Since 2013, the board has required a formal 1 year fellowship as a condition of board eligibility. One can enter the field from a number of different primary specialties under the ABMS or the American Osteopathic Association, including internal medicine, family practice, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, neurology, and family practice, among others. Today there are >6500 board-certified palliative medicine physicians and >100 accredited fellowship programs in the US. Similarly, there are >18 000 certified nonphysician palliative care professionals in the US, per the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association.

With mounting evidence demonstrating the many benefits of integrated palliative care for patients with serious illness, the demand for palliative care services has also increased dramatically.16 Despite the rapid growth in the palliative care services, data suggest that the current palliative care workforce would need to be at least tripled to meet this growing demand.17 Given the expanding role that palliative care is playing in the care of patients with serious illness, there is a need to further increase the palliative care workforce to meet those demands.

What do palliative care clinicians do?

Trained palliative care specialists receive explicit, advanced education in a number of areas that are highly useful in the care of patients with serious illness. Core competencies of fellowship training programs include symptom and quality-of-life assessment, complex symptom management, communication skills, spiritual assessment, family-centered care, and high-quality end-of-life care (including but not limited to “hospice care”). The value of adding these expert domains to the care of patients with advanced cancer has been demonstrated in a number of robust clinical trials, which are described in greater detail in the next section.

In one prominent example, a randomized controlled trial of early palliative care among patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer,4 palliative care specialists spent their time focusing on 3 primary things: (1) managing symptoms, (2) engaging patients in emotional work to facilitate coping, accepting, and planning; and (3) serving as a bridge between the oncologist and the patient, helping to interpret the oncologist for the patient, and the patient for the oncologist.18 Analysis of other data from this study confirms that palliative care visits have distinct features from oncology clinic visits, and that the roles of each clinician are complementary in the care of patients with advanced cancer.19 Evidence also suggests that patients say very different things to their oncologist than they say to their palliative care clinician.18-20 Furthermore, oncologists who already have experience collaborating with palliative care specialists tend to describe how helpful it is to have another expert available for managing complex cases or very time-consuming psychosocial issues.21 Moreover, oncology trainees do not receive adequate training in many of these areas, such as complex pain management skills, lending further support to the notion that palliative care clinicians are uniquely-trained, and possess additional expertise in these areas beyond that which a typical hematologist/oncologist provides.22

What is the evidence base behind palliative care?

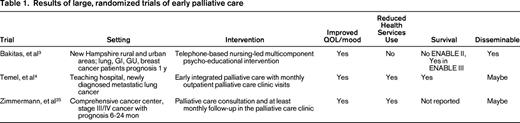

Three well-designed randomized controlled trials have clearly established the feasibility and benefits of integrating early palliative care concurrently with standard oncology care (Table 1). In Project ENABLE II, 322 patients with a diagnosis of gastrointestinal, lung, genitourinary, or breast cancer with a prognosis of ∼1 year were randomized within 8-12 weeks of their diagnosis to a palliative care intervention versus usual oncology care.3 The intervention was a multicomponent, psycho-educational, palliative care-focused intervention delivered in a manualized, telephone-based format by palliative care advanced practice nurse practitioners to a rural patient population in New Hampshire. Recipients reported significantly higher quality-of-life scores and had less depression, along with a trend toward lower symptom intensity compared to those receiving usual care. Of note, there were no differences in hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, emergency department visits, or hospice utilization between the 2 study arms.

In a study by Temel et al, 150 patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer were randomized to early integrated palliative care versus standard oncology care, within 8 weeks of diagnosis.4 Recipients visited outpatient palliative care clinics within 3 weeks of enrollment, with at least monthly follow-up thereafter. The palliative care visits were not scripted or manualized but followed general palliative care guidelines as per the national consensus project for quality palliative care.4,23 Patients randomized to the palliative care intervention had significant improvements in their quality-of-life, mood, and prognostic understanding.4,24 Additionally, patients receiving early palliative care were less likely to use chemotherapy at the end-of-life, more likely to use hospice services, and actually also lived longer.

In a randomized controlled study of 461 Canadian patients with stage III/IV solid tumors with a poor prognosis of 6-24 months, medical oncology clinics were cluster-randomized to early palliative care versus usual oncology care.25 Similar to the prior study by Temel et al, the intervention included a palliative care consultation within 1 month of study enrollment with at least monthly follow-up visits. The intervention included routine, structured assessments of symptoms and psychosocial needs, and discussion about home care needs. Patients randomized to the intervention reported better quality-of-life, higher satisfaction with care, and lower symptom burden at 4 months. Moreover, patients receiving early palliative care received more inpatient palliative care consultations and palliative care unit admissions, as well as referrals to palliative home nursing.

Together, these studies show that early palliative care improves patients' quality-of-life, mood, symptom burden, and other key aspects of cancer care including prognostic awareness, satisfaction with care, and quality of end-of-life care. Additionally, in a recent randomized controlled trial of early versus delayed palliative care (ENABLE III) for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer, family caregivers receiving the early palliative care intervention reported less depression and stress burden, highlighting the importance of palliative care in addressing the needs of families struggling with cancer.6 These studies also depict the efficacy of diverse palliative care delivery models, including telephone-based interventions, which may permit for easier dissemination of palliative care services for many patients with cancer, even those receiving their care in rural settings without direct access to specialty palliative care clinics.

The impact of early palliative care on patients' end-of-life care preferences and health services utilization is not consistent among these studies. In two studies, early palliative care clearly impacted health care utilization at the end of life,4,25 whereas in Project ENABLE, no such differences were noted. This may be due to the “intensity” of the palliative care intervention. The two studies with a measurable impact on health services utilization at the end of life entailed in-person palliative care clinic visits, whereas Project ENABLE focused on telephone-based palliative care psycho-educational interventions. More “intensive” palliative care models might be necessary to impact patients' decisions about medical care, which can ultimately alter health services utilization at the end of life.

Early palliative care may also improve survival. This was first reported by Temel et al in their early palliative care study for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer.4 Patients randomized to early palliative care had a median survival of 11.6 months versus 8.9 months (P = .02). In the ENABLE III study, patients randomized to early versus delayed palliative care also had a significant improvement in their survival.5 These findings strongly countered the misconceptions and fears that many oncologists held regarding palliative care leading to hopelessness and early death, or inappropriate reductions in use of effective palliative chemotherapies. Although the mechanism by which palliative care improves survival is not fully clear, improvement in patients' quality-of-life and mood may account for the observed survival benefit. Previous data have shown that lower quality-of-life and depressed mood are associated with shorter survival among patients with cancer.26-29 Additionally, the early integration of palliative care with standard oncology care may facilitate optimal and appropriate care at the end-of-life, leading to overall clinical stability and prolonged survival.

Amid this growing evidence of the numerous benefits of palliative care for patients with cancer, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) released its provisional clinical opinion in 2012 recommending concurrent palliative care from the time of diagnosis for all patients with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden.12 However, as of yet, there is no formal recommendation about palliative care involvement in hematologic malignancies. Notably, studies examining the integration of early palliative care for patients with hematologic malignancies are lacking. Although many experts in palliative care and outcomes research would argue that the current evidence base can and should be extrapolated to patients with hematologic malignancies, studies exploring integrated care models in patients with hematologic malignancies are also needed to further corroborate the findings seen in solid tumor settings, and to better define and describe unique needs in this diverse population.

Who should provide palliative care?

Clinicians who treat patients with cancer provide a great deal of palliative care independent of palliative care specialists. Indeed, most of the palliative care provided to cancer patients is this type, what some have called “primary palliative care”, or “generalist palliative care.” 16 This may include supportive care interventions like anti-emetics along with chemotherapy, management of cancer-related pain, or discussions about prognosis and prognostic understanding. Notably, involving palliative care specialists in the care of patients with hematologic malignancies should not, and is not meant to, replace the primary palliative care that is already being provided by the hematologist-oncologists. In fact, there are not enough palliative care specialists in practice to see every patient with cancer,17 nor is it reasonable to think that they should.16 Instead, we suggest that palliative care specialists are most instrumental in the care of patients with high symptom burden and complex symptom management needs, or in challenging situations with significant prognostic uncertainty and a relatively poor prognosis. In these circumstances, palliative care specialists can: (1) provide additional expertise to facilitate optimal symptom management and effective communication; (2) facilitate more effective coping, accepting, and planning for patients dealing with a lot of prognostic uncertainty; and (3) serve as a communication bridge between the hematologist-oncologist and the patient, especially in situations when the patient does not fully discuss their fears and concerns with the oncology team.

What are the palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies?

Patients with hematologic malignancies experience a physical and psychological symptom burden that is comparable to or exceeding that of patients with advanced solid tumors including pain, mucositis, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, constipation, and diarrhea.8,30,31 In a cross-sectional study of 180 patients with hematologic malignancies, patients had a considerable physical and psychological symptom burden, with an overall mean of 8.8 symptoms.9 The mean symptom burden was significantly greater in those on treatment, those with poorer performance status, inpatients, and those with more advanced disease. In another retrospective study comparing the symptom burden of patients with hematologic malignancies to those with advanced solid tumors, the median number of symptoms and overall symptom severity was similar between groups.30

Other studies have shown a significant decline in quality-of-life, increase in depressive symptoms, and a high symptom burden in patients with hematologic malignancies during their hospitalization for stem cell transplantation.32 Given the intense therapy that many patients with hematologic malignancies receive, a complex symptom profile ensues. Research is needed to explore whether palliative care specialists can help manage these symptoms and reduce the short and long-term physical and psychological sequelae of high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation.32

In addition to the physical and psychological symptom burden, data suggest that many patients with hematologic malignancies may not be receiving high quality end-life care.33,34 They are often hospitalized during the last month of life and frequently die in the hospital. Moreover, they more often die in the intensive care unit and/or receive chemotherapy during the last month of life.33,34 Despite their significant needs, patients with hematologic malignancies rarely utilize palliative care services compared to patients with solid tumors.7,34

Who needs palliative care?

As discussed previously, a growing body of literature suggests that patients with hematologic malignancies have unmet palliative care needs.7,9,35-37 However, many hematologist-oncologists who treat hematologic malignancies do not have experience partnering with palliative care clinicians in the care of their patients, or may harbor mistrust or misconceptions about palliative care.38 In the absence of clinical trials data demonstrating the value of defined interventions for particular hematologic malignancies, there are a number of scenarios that should prompt clinicians to consider involving a palliative care specialist. These are highlighted in Table 2. It is important to note that these scenarios are recommended based on the outcome improvements with palliative care in solid tumor patients. Future work should focus on evaluating the specific needs of patients with hematologic malignancies and examine the role of targeted palliative care interventions to address these needs.

Overcoming objections: addressing common concerns about palliative care in hematologic malignancies

In this section we will highlight common objections to palliative care in patients with hematologic malignancies and suggest ways to overcome them, with an eye toward increasing palliative care integration into comprehensive care of this vulnerable population.

“Patients will think I'm giving up” or “Patients don't like the word ‘palliative’”

This concern is rooted in a dated view of palliative care as something only appropriate for patients who are dying or who have no remaining treatment options. A recent public opinion poll demonstrates that most lay Americans have actually never heard the word “palliative”, and that they do not know what it means.39 Therefore, it is unreasonable to assume that patients will have negative perceptions of palliative care. This poll also showed that once people learn more about palliative care they become very interested in receiving it for themselves or a loved one. Perhaps hematologist-oncologists are more worried about the word “palliative” than we really should be. With appropriate introduction and education regarding palliative care, we can overcome this obstacle. Modern palliative care, as described above, can be provided upstream alongside curative cancer-directed therapy. As such, palliative care is a highly useful adjunct to the care already being provided by the hematologist-oncologist, and need not be an “either/or” proposition. Palliative care can help patients with cancer live better while receiving active treatment and it may allow them to better tolerate effective therapies. We should no longer feel forced to make decisions between chemotherapy and palliative care, as patients often benefit from both, and should be able to receive them simultaneously.

“I don't want to take away hope”

Hematologist-oncologists who care for patients with cancer often feel it is their responsibility to maintain patients' hope.40 As a corollary, it is often assumed that talking about a poor prognosis or end-of-life issues will squelch patients' spirits and dash their hopes. However, when patients are asked about their preferences, they overwhelmingly say that they want open, honest disclosure of prognosis, even when the news is bad.41,42 Furthermore, patients and families generally object to the notion that their doctor might keep information from them.43 Patients receiving palliative care are also able to transition their hopes from a complete focus on cure to hoping for other important goals, such as good symptom control, prolonging life while preserving quality-of-life, and spending quality time with their loved ones. Such “transitions of hope” may lead to more effective coping and acceptance especially when the hope for cure is no longer possible. Therefore, the desire to “preserve hope” does not preclude honest discussions about prognosis or goals of care, nor is it incompatible with palliative care referral. In fact, studies suggest that early palliative care can indeed facilitate a more accurate understanding of prognosis, which does not lead to more anxiety or depression.4,24

“I've had negative experiences with palliative care; they just want to make my patients DNR”

In interviews with hematologists-oncologists assessing barriers to palliative care referral, some reported negative experiences with palliative care.38 For example, a few hematologists-oncologists thought that palliative care clinicians have provided inaccurate prognostic information to their patients, or have pushed for a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order when it was not felt to be appropriate by the treating hematologist-oncologist. This is regrettable, and inappropriate; palliative care specialists should not have an agenda, rather they should seek to improve the quality-of-life and care for patients and families while respecting patients' and families' values and preferences. Moreover, palliative care specialists should collaborate closely with the treating hematologist-oncologist. Although hematologist-oncologists must understand that palliative care is not just a synonym for end-of-life care, our palliative care colleagues must also come to a better understanding of the challenges faced by patients with hematologic malignancies, particularly the degree of prognostic uncertainty associated with these diagnoses, and their different illness trajectories. This will develop with time, experience, and honest communication. In recent years, many solid tumor oncologists have come to trust and work collaboratively with palliative care specialists, despite facing similar negative experiences just a few years earlier. Hematologist-oncologists caring for patients with hematologic malignancies should also be capable of building similar collaborations with palliative care specialists. As we increasingly work together, palliative care specialists will come to better understand the unique challenges posed by hematologic malignancies, and help us to further improve the quality-of-life and care for this population.

“I do my own palliative care”

Cancer specialists serve most of the primary palliative care needs for patients with cancer. Furthermore, hematologist-oncologists are used to caring for patients independently; in other words, the multidisciplinary clinic that is typical of breast cancer care is not the norm in hematologic malignancies care, which is often provided by a lone hematologist-oncologist without much need for surgical or radiation oncologists. This level of independence and autonomy also leads to a strong feeling of ownership and a desire to meet all the needs of one's patients. On the other hand, solid tumor oncologists who work closely with palliative care specialists often describe how helpful it is to have additional support in managing the most complex and/or time-consuming issues facing their patients.21,38 Additionally, patients may engage in different conversations with different clinicians, focusing on cancer with the cancer specialist, and other issues like pain or psychosocial distress with the palliative care specialist.18-20 We also lack data to suggest that providers of primary palliative care can meet the higher-level specialty palliative care needs. Indeed, evidence suggests that oncology trainees lack competence at core specialty palliative care tasks, like doing basic opioid conversions.22 As more hematologic malignancy patients are seen by palliative care specialists, we will come to recognize that collaboration can improve the quality-of-life and care for patients with hematologic malignancies, via our complementary skill sets.

“Another clinician will just be disruptive”

It is not unusual for some patients with hematologic malignancies to live for a decade after their diagnosis, such as patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), multiple myeloma, and certain types of indolent lymphomas. One of the joys of hematologic malignancies practice is getting to know and follow patients longitudinally. As discussed, a strong sense of ownership may develop, which may bias hematologist-oncologists against involving a palliative care specialist in their patients' care.38 Experiences integrating palliative care into solid tumor care, however, have demonstrated that these concerns are largely unfounded.18 With the integrated oncology and palliative care approach, patients maintain strong relationships with their oncologists and do not perceive their care as being fragmented. Solid tumor oncologists often perceive a strong partnership with the palliative care specialist assisting them with complex symptom management, or psychosocial distress, for example.21 Rather than taking over a patient's care, palliative care specialists simply add an extra layer of support to the care already being provided by the primary oncology clinician. This practice respects and maintains the richness of the longitudinal relationship with the patient.

“There are not enough palliative care clinicians to care for all patients with hematologic malignancies”

Not all patients with hematologic malignancies require the involvement of specialist palliative care clinicians in their care. Similar to solid tumor oncology, many hematologist-oncologists already provide a great deal of “primary palliative care” to their patients with hematologic malignancies. In fact, primary palliative care is a critical component of oncology care. However, there are patients with more complex needs such as higher physical and psychological symptom burden, or difficult psychosocial circumstances, who may benefit from specialist palliative care services. Additional work is needed across all of oncology to augment primary palliative care skills, and to better define the population who will benefit the most from additional specialist input.

“The benefits of palliative care have only been seen in patients with solid tumors and therefore the data does not apply to my patients with hematologic malignancies”

Although there is a need for additional research to better define the palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies, it would be imprudent to brush off the many benefits of integrated palliative care as seen in multiple randomized studies. Given the comparable physical and psychological symptom burden in patients with hematologic malignancies and advanced solid tumors, it is very likely that patients with hematologic malignancies will significantly benefit from palliative care involvement.8,31 Arguably, given the intensity of many therapies given to patients with hematologic malignancies, and their unpredictable illness trajectory, these patients may actually benefit more from palliative care involvement than patients with solid tumors.31

Areas for future research

There are many reasons to think that palliative care will facilitate improved quality-of-life among patients with hematologic malignancies. However, there remains relatively little research defining the unique palliative care needs of this diverse population.10,44 Palliative care intervention studies in patients with hematologic malignancies are also lacking. Robust studies utilizing validated measures to assess patient reported outcomes, prognostic awareness, survival, and health services utilization are needed across the various diseases and throughout the illness trajectory. Studies must also recognize and address the specialized needs and trajectories of patients with hematologic malignancies during active cancer therapy as well as at the end of life45 compared to patients with solid tumors. We must develop targeted palliative care interventions based on the specialized needs of the diverse populations of patients with hematologic malignancies. For example, older patients with acute myeloid leukemia and multiple comorbidities are a highly vulnerable population with a poor prognosis, who may benefit greatly from early integration of palliative care to optimize symptom control and address end-of-life care needs.34 The needs of these patients are very different than those with hematologic malignancies who are undergoing stem cell transplantation, who may also benefit from palliative care involvement primarily to manage complex physical and psychological symptoms even when the goal is to cure.32 Last, we must also study and explore models for providing end-of-life care for patients with hematologic malignancies that can overcome typical limitations of hospice care in the US, which fails to recognize the palliative benefits of supportive transfusions and palliative chemotherapies, as these are often not provided as part of hospice care because of reimbursement limitations.31,46

Conclusion

Palliative care is now recommended as a standard part of comprehensive cancer care, yet most patients with a hematologic malignancy do not access palliative care specialists or services. Palliative care is not end-of-life care or hospice, but rather is a multidisciplinary approach to symptom management, psychosocial support, and assistance in treatment decision-making for patients with serious illness and their families. It emphasizes well-being at any point along the disease trajectory, regardless of prognosis. Currently, many patients with hematologic malignancies have significant palliative needs, and there are many unanswered questions on how to effectively integrate specialist palliative care into the care of our patients to meet those needs. Future work should focus on explicitly identifying the unique palliative care needs of the diverse hematologic malignancy population, and to develop and test models of integrated palliative and oncology care therein.

Correspondence

Thomas LeBlanc, Division of Hematologic Malignancies and Cellular Therapy, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Box 2715, DUMC, Durham, NC 27710; Phone: 919-668-1002; Fax: 919-668-1091; e-mail: thomas.leblanc@duke.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.