Abstract

Despite many recent advances in the treatment of multiple myeloma, the course of the disease is characterized by a repeating pattern of periods of remission and relapse as patients cycle through the available treatment options. Evidence is mounting that long-term maintenance therapy may help suppress residual disease after definitive therapy, prolonging remission and delaying relapse. For patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), lenalidomide maintenance therapy has been shown to improve progression-free survival (PFS); however, it is still unclear whether this translates into extended overall survival (OS). For patients ineligible for ASCT, continuous therapy with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone was shown to improve PFS and OS (interim analysis) compared with a standard, fixed-duration regimen of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide in a large phase 3 trial. Other trials have also investigated thalidomide and bortezomib maintenance for ASCT patients, and both agents have been evaluated as continuous therapy for those who are ASCT ineligible. However, some important questions regarding the optimal regimen and duration of therapy must be answered by prospective clinical trials before maintenance therapy, and continuous therapy should be considered routine practice. This article reviews the available data on the use of maintenance or continuous therapy strategies and highlights ongoing trials that will help to further define the role of these strategies in the management of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Learning Objectives

To understand the current role of maintenance therapy in the treatment of multiple myeloma in the era of novel agents

To review the data supporting the use of consolidation and maintenance therapy after autologous stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma

To describe the available evidence on the use of continuous therapy strategies for transplant-ineligible patients

To highlight unanswered questions regarding the use of maintenance therapy and continuous therapy and ongoing trials that may provide insights on the future of these treatment strategies in the management of patients with multiple myeloma

For most patients with multiple myeloma, the course of the disease is characterized by a series of remissions, followed by relapses.1-3 Relapse is attributed primarily to minimal residual disease (MRD) that persists after definitive therapy.1,4-6 This has led to interest in the use of novel therapies, including immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) and proteasome inhibitors, as consolidation and/or maintenance therapy after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) or as continuous therapy regimens for older, transplant-ineligible patients. Data from clinical trials indicate that this paradigm shift from fixed-duration therapy to continuous therapy may help suppress MRD and improve disease control.7-11 Although continuous therapy is increasingly used in the United States, routine use of this approach in daily practice remains controversial, particularly in the European Union. This article provides a brief review of the available data on novel agent-based maintenance or continuous therapy strategies for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Definition and aim of consolidation and maintenance therapy

The goal of using a short-term consolidation therapy after high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT is to improve disease control by deepening the response. Consolidation therapy consists of efficient combinations of agents, applied for a limited period of time (usually 2-4 cycles). Unlike consolidation therapy, maintenance therapy is less intensive and administered long term; biologically, the goal of maintenance therapy is to suppress any MRD with the clinical objectives of prolonging response duration, progression-free survival (PFS), and ultimately overall survival (OS) while minimizing toxicity. The terms consolidation and maintenance are mainly used in the post-ASCT setting. In transplant-ineligible patients, the term continuous therapy is usually preferred. Trials evaluating maintenance or continuous therapy often include the endpoint progression-free survival 2 (PFS2), which is defined as the time from randomization to second, objective disease progression or death from any cause, to ensure that the addition of maintenance therapy has no negative effect on the efficacy of next-line therapy.

Transplant-eligible patients

Maintenance therapy

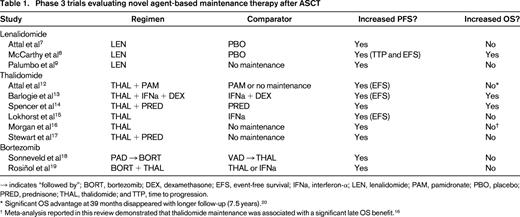

Numerous trials have evaluated the efficacy and safety of thalidomide, lenalidomide, and bortezomib as maintenance therapy after ASCT (Table 1).7-9,12-20 Thalidomide maintenance has been evaluated in 6 randomized trials12-15,17 and a meta-analysis,16 all of which showed a significant improvement in PFS with maintenance therapy. Two of these trials13,14 and the meta-analysis16 showed an improvement in OS. However, thalidomide is associated with cumulative toxicity, particularly peripheral neuropathy, which hinders long-term use.21 Reports of a negative effect of thalidomide maintenance on patient quality of life17 and survival outcomes in patients with high-risk cytogenetics16 have further reduced enthusiasm for using thalidomide in the maintenance setting.

Phase 3 trials evaluating novel agent-based maintenance therapy after ASCT

→ indicates “followed by”; BORT, bortezomib; DEX, dexamethasone; EFS, event-free survival; IFNa, interferon-α; LEN, lenalidomide; PAM, pamidronate; PBO, placebo; PRED, prednisone; THAL, thalidomide; and TTP, time to progression.

* Significant OS advantage at 39 months disappeared with longer follow-up (7.5 years).20

† Meta-analysis reported in this review demonstrated that thalidomide maintenance was associated with a significant late OS benefit.16

In 2 phase 3 trials,7,8 lenalidomide maintenance therapy, given at a dose of 10-15 mg daily (with possible dose reduction to 5 mg daily) until disease progression, significantly prolonged median PFS by almost 2 years compared with placebo. In the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) study,8 the majority of patients (74%) had received a thalidomide- or lenalidomide-containing induction regimen versus no patients in the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) study.7 The PFS benefit translated into an OS benefit in the CALGB study8 but not in the IFM study.7 These studies had several differences that may explain the conflicting OS results. For example, in the IFM study, all patients received lenalidomide consolidation before receiving maintenance therapy with either lenalidomide or placebo.7 Also, more patients in the lenalidomide group had high-risk cytogenetic features than those in the placebo group. These factors may help to explain, in part, the different OS outcomes in the two studies. In both studies, maintenance therapy with lenalidomide was generally well tolerated, but the incidence of hematologic adverse events did increase. An increased incidence of second primary malignancy (SPM) was noted in patients receiving lenalidomide maintenance in both studies, a risk that some have linked to concomitant or sequential use of lenalidomide and melphalan.22 Additional evidence of the positive effect of lenalidomide maintenance after ASCT can be derived from the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto RV-MM-PI-209 study,9 in which patients treated with ASCT or the combination of melphalan, prednisone, and lenalidomide (MPR) were randomized to lenalidomide maintenance or no maintenance therapy. Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide was associated with a significant improvement in median PFS (41.9 versus 21.6 months), although 3-year OS rates were similar in both groups (88.0% versus 79.2%, respectively).

Bortezomib-based maintenance therapy has been assessed in 2 randomized trials.18,19 In one trial, patients were randomized to induction therapy with bortezomib, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (PAD) or vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD); after ASCT, patients assigned to PAD received bortezomib maintenance every 2 weeks for 2 years, and patients assigned to VAD received thalidomide maintenance daily for 2 years.18 In a landmark analysis starting 12 months after randomization for patients who underwent ASCT and remained progression free, PFS and OS favored patients treated with PAD and bortezomib maintenance over those treated with VAD and thalidomide maintenance. However, the trial was not designed specifically to investigate maintenance, and it was not possible to separate the induction versus maintenance benefits of bortezomib. The safety profile of bortezomib was acceptable, although only 47% of patients were able to complete the planned 2 years of bortezomib maintenance therapy (compared with 27% of patients in the study who completed 2 years of thalidomide maintenance).18 In a second randomized trial, the combination of bortezomib and thalidomide (VT; one cycle of bortezomib given every 3 months with daily thalidomide) significantly prolonged PFS, but not OS, compared with thalidomide alone, and one-third of patients treated with VT required dose reductions.19 These 2 trials suggest that bortezomib represents a feasible maintenance strategy. However, it should be noted that both trials used intravenous bortezomib, which is associated with a less favorable toxicity profile than subcutaneous bortezomib, especially with regard to neurological toxicity. Therefore, the clinical outcome of patients may be improved with subcutaneous bortezomib by reducing the incidence of peripheral neuropathy and treatment discontinuation.

Consolidation therapy

In addition to long-term maintenance therapy, short-term consolidation therapy has been evaluated after ASCT. The purpose of this approach is to improve disease control by deepening post-ASCT response. Various regimens have been assessed, including the following: (1) 2 cycles of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD)23-25 ; (2) 2 cycles of lenalidomide7 ; (3) 6 weeks of weekly bortezomib26 ; and (4) 2 cycles of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD).27 In the latter phase 2 study,27 VRD consolidation was found to be promising in terms of response and PFS, with 50% of patients achieving a complete response and 58% being MRD negative after consolidation; estimated 3-year PFS was 77%. Data from comparative trials also support the ability of novel agent-based consolidation regimens to deepen post-ASCT response and improve PFS (Table 2).25,26 In one phase 3 study, patients randomized to VTD or thalidomide and dexamethasone (TD) as induction therapy before double ASCT received 2 cycles of the same regimen as consolidation therapy after ASCT.25 Rates of complete response or near-complete response were similar in both groups after ASCT but increased significantly in the VTD group after consolidation compared with the TD group (73.1% versus 60.9%). This translated into a PFS benefit: the 3-year PFS rate from the start of consolidation was significantly higher with VTD than TD (60% versus 48%).

Phase 3 trials evaluating novel agent-based consolidation therapy after ASCT

BORT indicates bortezomib.

Another consolidation approach that should be mentioned is the use of a second ASCT. In a recent retrospective study, double ASCT was found to be more beneficial than single ASCT for patients with poor prognosis, namely, those with high-risk cytogenetics and those who achieved less than complete response after induction therapy.28 The ongoing U.S. Stem Cell Transplant in Myeloma Incorporating Novel Agents (StAMINA) trial [Bone Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) 0702; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01109004] will be of key importance in defining the role of post-ASCT consolidation. In this trial, whose results are eagerly awaited, patients have been allocated randomly to no consolidation, VRD consolidation given for 4 cycles, or a second ASCT.

However, the influence of consolidation therapy on OS has not been established definitively and will be difficult to assess because of its short duration in the treatment program. Another unanswered question is whether consolidation therapy is more effective than a long induction therapy, for example, if 4 cycles of induction followed by ASCT and 2 cycles of the same regimen given as consolidation are better than 6 cycles of induction followed by ASCT and no consolidation. This would support the fact that the same chemotherapy may have a different efficacy before and after ASCT. If this is true, it would strongly support the use of consolidation therapy as part of routine clinical practice.

Future directions

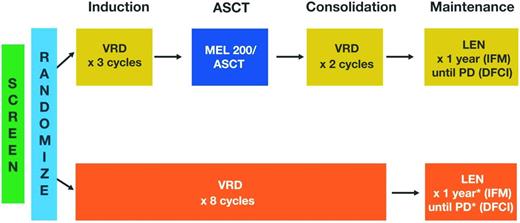

The available data on maintenance therapy after ASCT is promising, but one key issue remains unanswered: the optimal duration of therapy.21 Our understanding of the biology of multiple myeloma and MRD suggests that continuous therapy until clinical progression may be warranted,5,6 but this must be weighed against the safety risks, inconvenience, and costs of long-term therapy. Current trials are evaluating various durations of maintenance therapy, ranging from 1 to 3 years or until the time of progression. For example, in the StAMINA trial (BMT CTN 0702; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01109004), which is investigating the role of ASCT in consolidation therapy, all patients will receive lenalidomide maintenance therapy for 3 years. In an ongoing, phase 3, randomized trial conducted jointly by the IFM and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), lenalidomide maintenance will be given for 1 year by the IFM group (clinicaltrialsregister.eu: EudraCT 2009-016871-32) and until disease progression by the DFCI group (DFCI 10-106; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01208662; Figure 1). Ongoing trials are also attempting to improve the efficacy of lenalidomide maintenance by combining it with other novel therapies, such as the proteasome inhibitors carfilzomib (FORTE; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02203643) or ixazomib (GEM2014MAIN; clinicaltrialsregister.eu: EudraCT 2014-000554-10). Maintenance therapy using monoclonal antibodies, such as daratumumab [IFM and Hemato-Oncologie voor Volwassenen Nederland (HOVON) MMY-3006 (IFM-sponsored study); ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02541383] will also be investigated in upcoming trials (Figure 2). In the future, because of the availability of several agents, personalized maintenance based on risk assessment may also be investigated in terms of content (single agent versus combined maintenance) and duration (short versus long maintenance). In a recent report, VRD maintenance for up to 3 years (followed by single-agent lenalidomide maintenance thereafter) has shown promising results in terms of PFS (median of 32 months) and OS (>90% at 3 years) in patients with high-risk cytogenetics.29

Study design of ongoing phase 3 IFM/DFCI trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01208662). LEN indicates lenalidomide; and MEL 200, 200 mg/m2 melphalan. *MEL 200/ASCT given at relapse.

Study design of ongoing phase 3 IFM/DFCI trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01208662). LEN indicates lenalidomide; and MEL 200, 200 mg/m2 melphalan. *MEL 200/ASCT given at relapse.

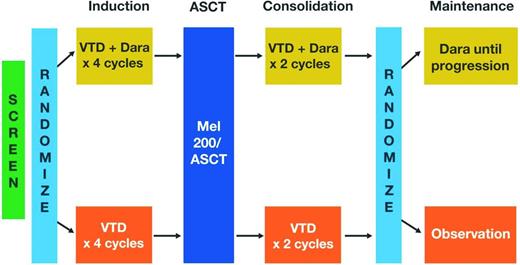

Study design of ongoing phase 3 IFM/HOVON MMY-3006 trial. Dara indicates daratumumab; and MEL 200, 200 mg/m2 melphalan.

Study design of ongoing phase 3 IFM/HOVON MMY-3006 trial. Dara indicates daratumumab; and MEL 200, 200 mg/m2 melphalan.

Current studies continue to assess various consolidation strategies. The aforementioned StAMINA trial (BMT CTN 0702; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01109004) is a key study that may provide additional insights on the benefits of second ASCT or conventional consolidation. The European intergroup trial (EMN-02; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01208766) also includes a randomization to consolidation therapy with 2 cycles of VRD or no consolidation. The IFM/HOVON (MMY-3006) study will evaluate the addition of the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab to VTD induction and consolidation (Figure 2). Also of note, second-/third-generation proteasome inhibitors, IMiDs, and monoclonal antibodies may allow longer consolidation strategies than the current 2 cycles.

Summary: transplant-eligible patients

Despite some of the weaknesses in the existing data mentioned above, the available evidence generally supports the use of consolidation therapy and some type of maintenance therapy after ASCT. It is important to note that, as far as routine clinical practice is concerned, these approaches have been implemented differently across countries. Maintenance therapy is a rapidly evolving topic, and additional studies will be needed to define optimal regimens and their durations.

Transplant-ineligible patients

Continuous therapy

For elderly patients and younger patients who are not eligible for ASCT, standard treatment typically consists of melphalan and prednisone plus either bortezomib (VMP) or thalidomide (MPT) given for a fixed number of cycles.30,31 However, these regimens are used infrequently in the United States, where low-dose melphalan is often not considered a valuable treatment option. Recent studies have shown that continuous therapy may provide greater benefit than fixed-duration therapy (Table 3).10,11,32-38 In the large phase 3 Frontline Investigation of Revlimid and Dexamethasone versus Standard Thalidomide (FIRST) trial,11 continuous treatment with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone (Rd; given until disease progression) was compared with a standard, fixed-duration regimen of MPT or Rd given for a fixed number of cycles (Rd18). The study enrolled 1623 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; the median age was 73 years, ∼40% had International Staging System stage III disease, and 147 patients (9%) had severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) not requiring dialysis, making this study population representative of a real-life population. Continuous Rd reduced the risk of progression or death by 28% compared with MPT and was associated with longer PFS2, better OS at interim analysis, higher response rates, greater duration of response, and longer time to next antimyeloma therapy. Compared with MPT, continuous Rd was associated with a moderate increase in infections but less myelosuppression, neuropathy, and SPMs. Compared with fixed-duration treatment (Rd18), continuous Rd also reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 30% and significantly improved duration of response and time to next antimyeloma therapy. However, continuous Rd demonstrated only a marginal benefit compared with Rd18 in terms of PFS2 and OS (at interim analysis).

Phase 3 trials evaluating novel agent-based continuous therapy for transplant-ineligible patients

→ indicates “followed by”; mPR, low-dose MPR; R, lenalidomide; and T, thalidomide.

The positive results of the FIRST trial not only establishes a new standard of care (Rd) for transplant-ineligible patients but also represents a dual paradigm shift away from alkylator-based regimens given for a fixed duration to an alkylator-free regimen that is given continuously. Clinically, this change reflects a broader shift toward a chronic, long-term approach to disease management for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients.

Data from other studies also support continuous therapy approaches in this setting. In the MM-015 trial, MPR followed by lenalidomide maintenance (MPR-R) was compared with MPR alone and melphalan and prednisone (MP) alone.10 The MPR-R regimen was associated with a median PFS of 31 months, which was significantly higher than that achieved with MPR or MP (14 and 13 months, respectively). The time from randomization to start of third-line therapy (a surrogate for PFS2) was longer with MPR-R (39.7 months) compared with MPR (27.8 months) and was significantly longer with MPR-R compared with MP (28.5 months). This suggests the following: (1) continuous therapy provides a durable progression-free interval even when accounting for second-line therapy; and (2) long-term treatment with lenalidomide does not affect the efficacy of subsequent therapy.32 Notably, the greatest benefit in terms of PFS was observed in patients aged 65-75 years; older patients were more likely to require dose modification or discontinuation attributable to adverse events. Overall, the incidence of SPM was 7% with MPR-R or MPR compared with 3% with MP.10 The PFS curves from both the FIRST11 and MM-01510 trials showed that continuous treatment with lenalidomide significantly delayed myeloma relapse. However, continuous Rd was a safer and better tolerated regimen than MPR-R, especially for older patients.

Approaches using thalidomide as continuous therapy have been evaluated33,34 ; efficacy appears generally comparable with that of lenalidomide, but lenalidomide is better tolerated than thalidomide over the long term and is, therefore, preferred. In the phase 3 HOVON-87 trial,33 MPT followed by thalidomide maintenance (MPT-T) was compared with MPR-R. Median PFS and OS were comparable in both treatment groups, but grade 3 peripheral neuropathy was reported in 15% of patients during thalidomide maintenance compared with 1% with MPR-R. Similarly, in a study coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG-E1A06) that compared MPT-T with MPR-R,34 there was no significant difference in terms of PFS and OS between the treatment groups, but MPR-R was associated with significantly less toxicity and better quality-of-life scores at 12 months compared with MPT-T.

Bortezomib-based continuous therapy is also feasible. In a phase 3 trial, the combination of VMP plus thalidomide followed by maintenance therapy with bortezomib and thalidomide for 2 years (VMPT-VT) was compared with standard VMP (9 cycles) with no maintenance. VMPT-VT compared with standard VMP with no maintenance, respectively, significantly improved the complete response rate (38% versus 24%), PFS (35 versus 25 months), time to next therapy (47 versus 28 months), and OS (5-year OS, 61% versus 51%).35,36 In the GEM2005MAS65 trial,37,38 patients treated with VMP or bortezomib, thalidomide, and prednisone (VTP) induction therapy for 6 cycles were randomized to maintenance therapy with one conventional cycle of bortezomib every 3 months, plus either prednisone (VP) or thalidomide (VT); maintenance therapy was given for a maximum of 3 years. The complete response rate increased from 24% after induction up to 42% (39% for VP versus 46% for VT). The median PFS was long at 35 months but with no significant difference between the two groups (32 months with VP versus 39 months with VT); the 5-year OS rate was also not statistically different (50% versus 69%, respectively).

Last, a recent nonrandomized study including few transplant-ineligible patients has investigated the carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone regimen (8 cycles for induction followed by lenalidomide maintenance for 2 years) and shown promising preliminary results, especially in terms of achievement of MRD negativity.39

Future directions

Several ongoing phase 3 studies are comparing Rd therapy with the combination of Rd and another novel agent given continuously. These agents include elotuzumab (ELOQUENT-1 trial; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01335399), ixazomib (TOURMALINE-MM2 trial; clinicaltrialsregister.eu: EudraCT 2013-000326-54), and daratumumab (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02252172). Last, a National Cancer Institute–sponsored phase 3 trial will help determine whether the addition of bortezomib to the initial cycles of continuous therapy with Rd improves PFS (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00644228).

Summary: transplant-ineligible patients

Based on the available data, continuous therapy using novel agents appears to be beneficial for transplant-ineligible patients, at least in terms of PFS.21 The demonstrated efficacy and tolerability of the Rd regimen makes it a treatment onto which novel therapies may be added in an attempt to provide even greater disease control; several ongoing trials are currently evaluating novel Rd-based regimens.21

Summary

Increasing evidence supports the use of continuous therapy to delay relapse and, in some studies, to increase survival40 in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. This aligns with our increasing understanding of MRD and may improve the conventional pattern of repeated remissions and relapses by suppressing MRD and prolonging PFS.1,4-6 For transplant-eligible patients, consolidation will likely be an option in the future, although additional studies should help establish its role in the therapeutic strategy. Data from randomized trials support the use of maintenance after ASCT, and ongoing studies will provide more insights into the optimal regimen, schedule, and duration of maintenance therapy in this setting. The question of whether longitudinal monitoring of MRD status during the treatment course may help predict long-term outcome and inform duration of maintenance also deserves to be evaluated; recent39 and ongoing studies compared multicolor flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing as a metric for MRD. For transplant-ineligible patients, continuous therapy until disease progression with the alkylator-free Rd regimen represents a major paradigm change that will likely influence the standard approach to patient management. Future studies evaluating the addition of proteasome inhibitors and other novel therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies to the Rd backbone, may lead to additional improvements in outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support for this work was provided by Excerpta Medica (Keisha Peters), sponsored by Celgene Corporation.

Correspondence

Prof Thierry Facon, Hôpital Claude Huriez, Rue Michel Polonovski, CHRU Lille, F-59000 Lille, France; Phone: 33-3-20-44-57-12; e-mail: thierry.facon@chru-lille.fr.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is on the Board of Directors or an advisory committee for Celgene Corporation, Janssen, Millennium, Amgen, BMS, Novartis, and Pierre Fabre and has been affiliated with the Speakers Bureau for Celgene Corporation and Janssen.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: Lenalidomide.