Abstract

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a potentially fatal complication after anti-B-cell therapy. It can develop not only in patients seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), but also in those with resolved HBV infection who are seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) and/or antibodies against HBsAg (anti-HBs). The risk of HBV reactivation depends on the balance between replication of the virus and the immune response of the host. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody—rituximab in combination with steroid-containing chemotherapy (R-CHOP: rituximab + cyclophosphamide + hydroxydaunorubicin + vincristine + prednisone/prednisolone)—is an important risk factor for HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients. More obviously, HBsAg-positive patients are considered to be at very high risk for HBV reactivation and, in the rituximab era, 59%–80% of these patients develop HBV reactivation after R-CHOP-like chemotherapy. Patients with resolved HBV infection should also be considered at high risk of HBV reactivation, the incidence of which is reported to be 9%–24% in such lymphoma patients. All patients should be screened to identify risk groups for HBV reactivation before initiating anti-B-cell therapy by measuring serum HBV markers including HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs. To prevent the development of hepatitis due to HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for HBsAg-positive patients and/or patients in whom HBV DNA is detectable at baseline, whereas regular monitoring of HBV DNA-guided preemptive antiviral therapy is a reasonable and useful approach for patients with resolved HBV infection.

Learning Objectives

To become familiar with the risk of HBV reactivation in patients who receive anti-B-cell therapy

To manage such high-risk patients successfully using antiviral prophylaxis or by HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy

Introduction

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a potentially fatal complication after immunosuppressive therapy. HBV reactivation has been found, not only in patients seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg),1-3 but also in those with resolved HBV infection who are seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) and/or antibodies against HBsAg (anti-HBs).1,4-9

Rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy has been identified recently as an important risk factor for HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection.5,6 Rituximab is a chimeric mouse-human monoclonal antibody that targets the CD20 molecule. Approximately 70%–80% of malignant lymphomas are of B-cell origin and >90% of B-cell lymphomas express CD20 on the cell surface. The introduction of rituximab has markedly improved outcomes in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas.10 R-CHOP (rituximab + cyclophosphamide + hydroxydaunorubicin + vincristine + prednisone/prednisolone) is the most widely used for these types of lymphoma. Moreover, the usefulness of rituximab has also been demonstrated in patients with certain refractory autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis,11 granulomatosis with polyangitis,12 and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.13

The great success of rituximab is being followed by the development of new monoclonal antibodies to CD20. Ofatumumab is a human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that has been shown to be effective in refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia.14 Obinutuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody, which has been demonstrated to improve outcomes in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with coexisting conditions.15

More recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has presented new boxed warning information regarding the risk of HBV reactivation in patients who receive rituximab or ofatumumab.9 To decrease the risk of HBV reactivation, the safety announcement recommends screening all patients for HBV infection before starting treatment with these anti-B-cell antibodies and monitoring patients with prior HBV infection in consultation with hepatitis experts after immunosuppressive therapy.

In this review, we summarize the current evidence regarding HBV reactivation in patients with hematological malignancies after immunosuppressive therapy, including anti-B-cell therapy, and propose a strategy for managing HBV reactivation, especially in patients with resolved HBV infection.

Pathophysiology of HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy

In most immunocompetent hosts, HBV infection manifests as acute hepatitis. The host immune response targets the infected hepatocytes, after which serum HBV DNA and HBsAg levels gradually decrease to below the detection limit over several months or years. Most cases of acute hepatitis B completely resolve in adult patients, who become seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs. However, HBV replication may chronically persist in the liver,16 even in patients with anti-HBs, for several years after acute hepatitis B. Because HBV covalently closed circular DNA remains present in hepatocytes and provides a stable template for replication of HBV, viral reactivation has been reported after immunosuppressive therapy even in patients with resolved HBV infection. All individuals with a history of exposure to HBV should therefore be considered at risk of HBV reactivation. Under immunosuppressive conditions, HBV is more likely to replicate rapidly and to infect many hepatocytes. Subsequently, the recovered immunocompetent cells can attack the HBV-infected hepatocytes, resulting in the recurrence of hepatitis B.

Clinical manifestations of HBV reactivation range from asymptomatic, self-limiting to fulminant hepatitis, which can be fatal in some patients despite best supportive care. It is difficult to predict individual patient outcome after HBV reactivation.

How does anti-B-cell therapy increase the risk of HBV reactivation? Immune control of HBV infection is considered to be maintained mainly by HBV-specific cytotoxic T cells,16 and the role of B cells has not yet been clearly elucidated. Therefore, the mechanism of HBV reactivation associated with anti-B-cell therapy is not fully understood.

Risk of HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy

The risk of HBV reactivation depends on the balance between replication of the virus and the immune response of the host. In patients who receive immunosuppressive therapy, including anti-B-cell therapy, the risk of HBV reactivation varies according to the HBV infection status at baseline, but also with the intensity of immunosuppression.

Important viral factors for HBV reactivation have been reported to be high HBV DNA levels and serum HBV markers such as HBeAg, HBsAg, and anti-HBc.3,6,17,18 Occult HBV infection, which is defined as seronegativity for HBsAg, but with detectable of HBV DNA in the blood or liver, may be one of the important risk factors.5 Genotypes and gene mutations of HBV, which are associated with the enhancement of HBV replication and fulminant hepatitis, have also been reported to be associated with outcome in patients with HBV reactivation.19,20

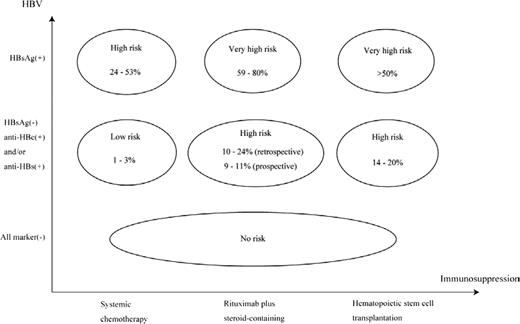

Conversely, steroid-containing chemotherapy has been reported to be an important host risk factor associated with HBV reactivation, partly because of glucocorticoid stimulation of a glucocorticoid-responsive element in the HBV genome leading to up-regulation of HBV gene expression. Actually, in the pre-rituximab era, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that steroid-containing chemotherapy increased the incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients; the relative risk of steroid-containing versus steroid-free was 1.9 (95% confidence interval = 1.1-3.4).21 The rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy has recently been demonstrated to be a risk factor for HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients,5,6 HBV reactivation is a well-known complication after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) because of the long-term use of immunosuppressive drugs and the gradual immune reconstitution after HSCT.22,23 Additional host risk factors for HBV reactivation have been reported as male sex,6 diagnosis of lymphoma,3 absence of anti-HBs at baseline,6,24 and decrease of anti-HBs titers after immunosuppressive therapy.25 The risk classification for HBV reactivation according to serum HBV markers and the intensity of immunosuppressive therapy can be determined based on the current evidence (Figure 1).7

Risk classification of HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy. The vertical axis shows the HBV infectious status at baseline according to serum HBV markers before immunosuppressive therapy. The horizontal axis shows the intensity of immunosuppression after immunosuppressive therapy. The incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients who received systemic chemotherapy, rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy, or HSCT has been reported to be 24%–53%, 59%–80%, and >50%, respectively. In patients with resolved HBV infection (anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive in HBsAg-negative patients), the incidence of HBV reactivation has been reported to be 1%–3% after systemic chemotherapy, 10%–24% (by retrospective study) and 9%–11% (by prospective study) after rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy, and 14%–20% after HSCT. HBsAg-negative patients seronegative for anti-HBc and anti-HBs (all marker-seronegative at baseline) are considered to be at no risk for HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy. This figure is modified and cited from Kusumoto et al7 with permission from The Japanese Society of Hematology.

Risk classification of HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy. The vertical axis shows the HBV infectious status at baseline according to serum HBV markers before immunosuppressive therapy. The horizontal axis shows the intensity of immunosuppression after immunosuppressive therapy. The incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients who received systemic chemotherapy, rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy, or HSCT has been reported to be 24%–53%, 59%–80%, and >50%, respectively. In patients with resolved HBV infection (anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive in HBsAg-negative patients), the incidence of HBV reactivation has been reported to be 1%–3% after systemic chemotherapy, 10%–24% (by retrospective study) and 9%–11% (by prospective study) after rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy, and 14%–20% after HSCT. HBsAg-negative patients seronegative for anti-HBc and anti-HBs (all marker-seronegative at baseline) are considered to be at no risk for HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy. This figure is modified and cited from Kusumoto et al7 with permission from The Japanese Society of Hematology.

HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients after anti-B-cell therapy

HBV reactivation often occurs in HBsAg-positive patients after immunosuppressive therapy even if steroid alone is given. In the pre-rituximab era, HBsAg-positive patients were considered to be at high risk for HBV reactivation and it was reported that 24%–53% of these patients developed HBV reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy. Yeo et al reported that HBV reactivation was observed in 47 of 193 (24%) lymphoma patients seropositive for HBsAg who received systemic chemotherapy.3 Lok et al reported that 13 of 27 (48%) HBsAg-positive patients developed HBV reactivation after lymphoma treatment.1 Lau et al conducted a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of antiviral prophylaxis in 30 HBsAg-positive patients with malignant lymphoma after systemic chemotherapy.2 No reactivation occurred in patients who received antiviral prophylaxis, but 8 of 15 (53%) patients without prophylaxis had HBV reactivation. In the rituximab era, there is limited evidence regarding the risk of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients after anti-B-cell therapy because it has been widely recognized that antiviral prophylaxis is necessary to prevent HBV-related hepatitis for such high-risk patients. Pei et al reported that 8 of 10 (80%) HBsAg-positive patients developed HBV reactivation in a retrospective analysis.26 More recently, Kim et al conducted a multinational retrospective study to evaluate the incidence of HBV reactivation and its risk factors and found that 13 of 22 (59%) HBsAg-positive patients had HBV reactivation without antiviral prophylaxis.24

HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients (with resolved HBV infection) after anti-B-cell therapy

In the pre-rituximab era, the risk of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-negative patients with lymphoma after systemic chemotherapy was considered to be low. Lok et al reported that only 2 of 72 (3%) HBsAg-negative patients developed HBV reactivation compared with far more HBsAg-positive patients (13 of 27, 48%).1 However, it is likely that the introduction of rituximab has increased the risk of HBV reactivation, which has often been reported especially in HBsAg-negative patients who received rituximab-containing chemotherapy. Dervite et al first reported that fatal HBV reactivation occurred in HBsAg-negative but anti-HBs-positive patients who received R-CHOP in 2001.4 In 2006, Hui et al conducted a retrospective study of 244 HBsAg-negative lymphoma patients receiving systemic chemotherapy, 8 of whom (3%) developed hepatitis due to HBV reactivation. All 8 of these patients were seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs.5 Multivariate analysis showed that rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapy was an independent risk factor for HBV reactivation compared with other combined chemotherapy (6 of 49,12%, vs 2 of 195, 1%, respectively). In 2009, Yeo et al also reported that 5 of 80 (6%) HBsAg-negative patients who were diagnosed as having diffuse large B-cell lymphoma developed HBV reactivation after R-CHOP or CHOP-like regimens.6 All 5 of these patients were anti-HBc-positive and received R-CHOP, meaning that 5 of 21 (24%) patients seropositive for anti-HBc had HBV reactivation after R-CHOP. In 2013, Kim et al also showed that 16 of 153 (10%) HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive patients developed HBV reactivation after R-CHOP in a multinational retrospective analysis.24

Summary of the characteristics and outcome of 211 Japanese patients developing serious hepatitis B after rituximab-containing chemotherapy

According to the data collected by the Zenyaku Kogyo Company and the Chugai Pharmaceutical Company of Japan between September 2001 and August 2013, 211 Japanese patients developed serious hepatitis B after rituximab-containing chemotherapy. These data included clinical information that were collected retrospectively from medical practices, spontaneous reports to the company, reports at academic meetings, and results from several investigational studies and clinical trials.

The HBsAg status before rituximab-containing chemotherapy was available in 175 patients: 66 (38%) were HBsAg-positive and 109 (62%) were HBsAg-negative. Of the latter, the anti-HBc status before initiating rituximab-containing chemotherapy was known in only 33 (30%). Of these, 32 (97%) were anti-HBc-positive and the remaining one was anti-HBc-negative, whereas 8, 13, and 12 were anti-HBs-positive, anti-HBs-negative, and with unknown anti-HBs status, respectively.

Of the 109 HBsAg-negative patients, 88 (81%) received rituximab + steroid-containing chemotherapies such as R-CHOP, 7 received a steroid-free regimen, 5 received HSCT, 1 received renal transplantation, 4 received rituximab alone, and 4 were not available for regimen information. Antiviral prophylaxis was administered in 21 of 66 HBsAg-positive and 2 of 109 HBsAg-negative patients. Of the HBsAg-negative patients, the incidence of fulminant hepatitis (32 of 109, 29%) and mortality (51 of 109, 47%) was higher in the HBsAg-positive patients (14 of 66, 21%, and 20 of 66, 30%, respectively). Median time to onset of hepatitis B from the last administration of either rituximab or other chemotherapy regimen in HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients was 5.5 and 9.1 weeks, respectively. Most of the HBsAg-negative patients developed hepatitis within 1 year after completion of chemotherapy, but 2 developed hepatitis >1 year after chemotherapy.

Screening for HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy

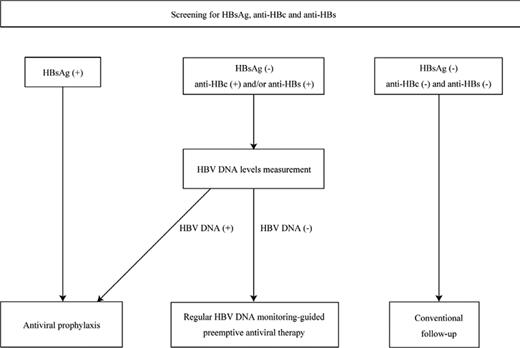

HBV infection should be screened in all patients before initiating anti-B-cell therapy regardless of the presence of hepatitis, type of disease, and combined chemotherapy. To identify the 3 following risk groups for HBV reactivation, serum HBV markers including HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs should be measured before initiating immunosuppressive therapy (Figure 2).7,27,28 If an individual is seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs, then baseline HBV DNA levels should be measured in addition to the serum markers. The 3 risk groups are as follows.

Flowchart illustrating the strategy for preventing hepatitis due to HBV reactivation. All patients are screened before starting anti-B-cell therapy by measuring serum HBV markers including HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs to identify groups at risk of HBV reactivation. If an individual is seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs, baseline HBV DNA levels are measured in addition to the serum markers. To prevent hepatitis due to HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for HBsAg-positive patients and/or patients in whom HBV DNA is detectable at baseline, whereas regular monitoring of HBV DNA-guided preemptive antiviral therapy is a reasonable approach for patients with resolved HBV infection who are seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs. This figure is modified and cited from Kusumoto et al7 with permission from The Japanese Society of Hematology.

Flowchart illustrating the strategy for preventing hepatitis due to HBV reactivation. All patients are screened before starting anti-B-cell therapy by measuring serum HBV markers including HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs to identify groups at risk of HBV reactivation. If an individual is seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs, baseline HBV DNA levels are measured in addition to the serum markers. To prevent hepatitis due to HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for HBsAg-positive patients and/or patients in whom HBV DNA is detectable at baseline, whereas regular monitoring of HBV DNA-guided preemptive antiviral therapy is a reasonable approach for patients with resolved HBV infection who are seronegative for HBsAg but seropositive for anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs. This figure is modified and cited from Kusumoto et al7 with permission from The Japanese Society of Hematology.

Group 1 are HBsAg-positive patients. If an individual is seropositive for HBsAg, the additional following tests are recommended: HBV DNA levels, HBeAg, and anti-HBe.7,28 Group 2 are HBsAg-negative but with HBV DNA detectable. These patients are considered to have occult HBV infection and may be at high risk for HBV reactivation similar to HBsAg-positive patients.7,28,29 Because an individual with occult HBV infection is usually anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive, this risk group can be identified by additionally measuring HBV DNA levels if either HBV markers is seropositive. Group 3 are HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive and HBV DNA is not detectable. HBsAg-negative patients who are anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive without detectable HBV DNA are considered to have resolved their HBV infection. However, an individual who is seropositive only for anti-HBs with a history of vaccination against hepatitis B should be excluded from the risk group for HBV reactivation.28 Because HBV reactivation has also been reported in patients seropositive only for anti-HBs who were treated with anti-B-cell therapy,5 such patients require careful attention and should not be excluded from the risk group for HBV reactivation, especially in countries that have adopted universal vaccination against hepatitis B.

The identification of these risk groups for HBV reactivation is strongly recommended before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, because this may decrease titers of serum HBV antibodies and make it difficult to evaluate the risk of HBV reactivation.28 It is also recommended to use high-sensitivity testing kits when HBV-related markers are measured.28

Management of HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy

Initiating antiviral treatment after the occurrence of overt hepatitis is insufficient to control HBV reactivation. Yeo et al conducted a prospective study showing that 5 (16%) patients died and 22 (69%) required modification of the planned chemotherapy schedule among 32 patients who received lamivudine as an antiviral drug for hepatitis due to HBV reactivation.3 Umemura et al reported that the incidence of fulminant hepatitis and mortality in patients with HBV reactivation was higher than in acute hepatitis B in a retrospective analysis.19 Therefore, it is necessary to identify these high-risk groups before initiating immunosuppressive therapy and to start antiviral treatment immediately before hepatitis onset after HBV reactivation.

Currently, there are 2 options to preventing hepatitis due to HBV reactivation: (1) antiviral prophylaxis, in which an antiviral drug is given before initiating immunosuppressive therapy, and (2) regular HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy, in which an antiviral drug is given if HBV DNA in the blood becomes detectable by regular monitoring.

Strategy to prevent HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients

For HBsAg-positive patients (Risk Group 1) undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, antiviral prophylaxis is essential (Figure 2), as recommended by some guidelines.28,30,31 Antiviral prophylaxis should also be given to patients who are HBsAg-negative but who have detectable HBV DNA (Risk Group 2), who are potentially at a higher risk for HBV reactivation (Figure 2).7,28,29 The incidence of HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients receiving rituximab-containing chemotherapy without antiviral prophylaxis has been reported to be 59%–80%.24,26 These patients are considered to constitute a very-high-risk group for HBV reactivation (Figure 1). Of the HBsAg-positive patients, most HBV reactivation occurs during and after chemotherapy, but patients with high HBV DNA levels at baseline potentially suffer HBV reactivation at an early stage of chemotherapy.7 Therefore, antiviral prophylaxis is necessary to prevent hepatitis due to HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients and/or patients in whom HBV DNA is detectable at baseline and should be started as soon as possible to reduce HBV DNA levels before immunosuppressive therapy.

Which drug is recommended in an antiviral prophylaxis setting to prevent HBV reactivation? Lamivudine is a first-generation nucleoside analog that can suppress HBV replication and improve hepatitis B. Some prospective studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of lamivudine for preventing HBV reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients who received immunosuppressive therapy.3,32 However, it was reported that there is a high incidence of acquired viral resistance to lamivudine, resulting in breakthrough hepatitis, especially in patients who received long-term antiviral prophylaxis with this drug. Lamivudine resistance was reported as 24% at 1 year and >50% at 5 years in patients with chronic hepatitis B.33

Entecavir and tenofovir are new-generation nucleoside analogs that have greater potential to suppress HBV replication and to which there is a lower incidence of viral resistance mutation.34,35 Entecavir resistance has been reported to be more likely to occur in patients with chronic hepatitis B who had prior lamivudine resistance compared with patients with previously untreated chronic hepatitis B.36 There has been no prospective study directly comparing entecavir with lamivudine for antiviral prophylaxis after immunosuppressive therapy. Kim et al recently reported that no HBV reactivation was observed in 31 HBsAg-positive patients who received entecavir, whereas 30 of 96 (31%) who received lamivudine developed HBV reactivation after R-CHOP-like regimens.24 Although the current evidence regarding prevention of HBV reactivation is insufficient for a definitive recommendation, it would seem that entecavir or tenofovir is better option as a first-line antiviral drug in view of the higher efficacy and less development of resistance.28

How long should we continue antiviral prophylaxis after anti-B-cell therapy? There is no consensus regarding the optimal duration of antiviral prophylaxis for HBsAg-positive patients. To establish when to discontinue the antiviral prophylaxis safely, we propose the following criteria as being essential: (1) planned immunosuppressive therapy completed, (2) undetectable HBV DNA levels by real-time PCR assay, and (3) both conditions 1 and 2 maintained at least for 1 year. More importantly, regular monitoring of HBV DNA for at least 6 months after discontinuation of antiviral prophylaxis is desirable to prevent HBV reactivation because reemergence of HBV was observed within 6 months after withdrawal of antiviral prophylaxis according to data collected by the Zenyaku Kogyo Company and the Chugai Pharmaceutical Company.

Strategy to prevent HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection (anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive in HBsAg-negative patients, Risk Group 3)

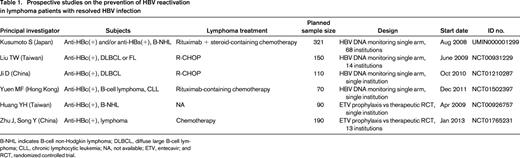

Although there is no consensus on a strategy to prevent HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection, regular HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy is a reasonable approach for such patients.7,28,37 Recently completed and ongoing prospective studies for preventing HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection are listed in Table 1. There are 2 study designs: preemptive antiviral therapy and antiviral prophylaxis.

Prospective studies on the prevention of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection

B-NHL indicates B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; NA, not available; ETV, entecavir; and RCT, randomized controlled trial.

What is the rationale for preemptive antiviral therapy? Hui et al reported that the median time from the elevation of serum HBV DNA to hepatitis onset was 18.5 weeks (range, 12–28) in a retrospective analysis,5 suggesting that increased HBV DNA levels were observable at least 3 months before clinical hepatitis in patients with resolved HBV infection. We hypothesized that monthly HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy can prevent hepatitis due to HBV reactivation7 and conducted a multicenter prospective study in Japan (Study UMIN000001299, Table 1).

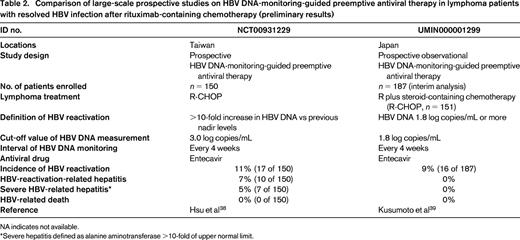

A comparison of large-scale prospective studies on HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection after rituximab-containing chemotherapy is shown in Table 2. These studies demonstrated that monthly monitoring of HBV DNA could prevent HBV-related death.38,39 However, in the Taiwanese study, 10 of 150 (7%) HBV-resolved patients who received R-CHOP developed hepatitis due to HBV reactivation and 7 of 150 (5%) developed severe hepatitis defined as alanine aminotransferase >10-fold the upper normal limit. Patients with HBV reactivation were more likely to have a poorer prognosis.38 The interim analysis of the Japanese study showed that serial monthly monitoring of HBV DNA is effective for preventing hepatitis due to HBV reactivation, with no hepatitis occurring in B-cell lymphoma patients with highly replicative HBV clones such as precore mutants.39

Comparison of large-scale prospective studies on HBV DNA-monitoring-guided preemptive antiviral therapy in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection after rituximab-containing chemotherapy (preliminary results)

NA indicates not available.

*Severe hepatitis defined as alanine aminotransferase >10-fold of upper normal limit.

Although the different results of these 2 studies may have been related to the definition of HBV reactivation and the cutoff values of HBV DNA measurement (Table 2), the Taiwanese study might indicate that a more sensitive assay of HBV DNA is required to prevent hepatitis on such the setting of preemptive antiviral therapy. These 2 studies also showed that most HBV reactivation was observed within 1 year after completion of rituximab-containing chemotherapy, which again suggests that the monitoring of HBV DNA should be continued for at least 1 year after the completion of anti-B-cell therapy. Conversely, although antiviral prophylaxis is an alternative approach to preventing HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection,40 there are some concerns, such as emergence of drug resistance and cost-effectiveness, that also need to be addressed.41

Conclusions

All patients should be screened before starting anti-B-cell therapy by measuring serum HBV markers including HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HBs to identify groups at risk of HBV reactivation. To prevent hepatitis due to HBV reactivation after anti-B-cell therapy, antiviral prophylaxis is recommended for HBsAg-positive patients and/or patients in whom HBV DNA is detectable at baseline, whereas regular monitoring of HBV DNA-guided preemptive antiviral therapy is a reasonable approach for patients with resolved HBV infection.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support was partly provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (Grant-in-Aid H24-kanen-004-MM). This study was also supported in part by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (Grant 26-S-4). We thank Dr. Yasuhito Tanaka (Department of Virology and Liver Unit, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Nagoya), Dr. Masashi Mizokami (The Research Center for Hepatitis and Immunology, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Ichikawa), and Dr. Ryuzo Ueda (Department of Tumor Immunology, Aichi Medical University School of Medicine, Aichi) for their enlightening advice on this review article; all of the investigators participating in the Japanese prospective nationwide observational study of HBV DNA monitoring and preemptive antiviral therapy for HBV reactivation in patients with B-cell lymphoma after rituximab containing chemotherapy; and the Zenyaku Kogyo Company and Chugai Pharmaceutical Company for providing clinical data on 211 patients developing serious hepatitis B after rituximab-containing chemotherapy.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: K.T. has received research funding from Zenyaku Kogyo and Chugai Pharmaceutical. S.K. has received research funding and honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Zenyaku Kogyo, and Abbott. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Kensei Tobinai, MD, PhD, Department of Hematology, National Cancer Center Hospital, 5-1-1 Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan. Phone: +81-3-3542-2511; Fax: +81-3-3542-3815; e-mail: ktobinai@ncc.go.jp.