Abstract

The increased survival of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) into adulthood is associated with an increased incidence of multiorgan dysfunction and a progressive systemic and pulmonary vasculopathy. The high prevalence of an elevated tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity and its association with an increased risk of death in adult patients is well established. However, there has been controversy regarding the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension (PH) and its association with mortality in SCD. Multiple recently published reports demonstrate that PH as diagnosed by right heart catheterization is common in adult SCD patients, with a prevalence of 6%–11%. Furthermore, PH is associated with an increased risk of death in SCD patients. In this chapter, we provide evidence for the high prevalence of PH in SCD and its association with mortality and make recommendations for its evaluation and management. Finally, we provide the rationale for screening for this life-threatening complication in adult patients with SCD.

Learning Objectives

To recognize the high prevalence of PH in adult patients with SCD

To recognize the association of PH with increased mortality in adult patients

To be able to describe the evaluation of PH in SCD and the available treatment options

Introduction

Sickle cell anemia is one of the most common monogenic disorders in the world, affecting an estimated 1%–4% of newborns in sub-Saharan Africa1 and ∼1 in 600 African Americans in the United States.2 It is an autosomal-recessive Mendelian disease that is caused by a single point mutation in the beta globin gene.3 This mutation results in the substitution of a glutamic acid residue with valine at position 6. Sickle cell disease (SCD) is characterized by recurrent episodes of vasoocclusion, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and chronic hemolysis. The survival of children with SCD in the United States has improved over the last several decades,4,5 a likely consequence of the implementation of newborn screening, use of prophylactic penicillin, and effective vaccinations against Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae.6-8 Furthermore, advances in RBC transfusion medicine, iron chelation therapy, and transcranial Doppler screening to prevent potentially devastating strokes9,10 may also play a role. However, the increased survival of patients into adulthood is associated with an increased incidence of multiorgan dysfunction and a progressive systemic and pulmonary vasculopathy.11,12 Comprehensive reviews of cardiac and pulmonary complications of SCD have been published,13,14 and guidelines for the diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of pulmonary hypertension (PH) in SCD have recently been released.15

With the concerns that have been raised regarding the prevalence and clinical implications of PH in SCD,16,17 we have asked several clinically important questions and make recommendations for the diagnosis and management of PH in these patients. In addition, we provide the rationale for screening for PH in patients with SCD.

What is the prevalence of PH in SCD?

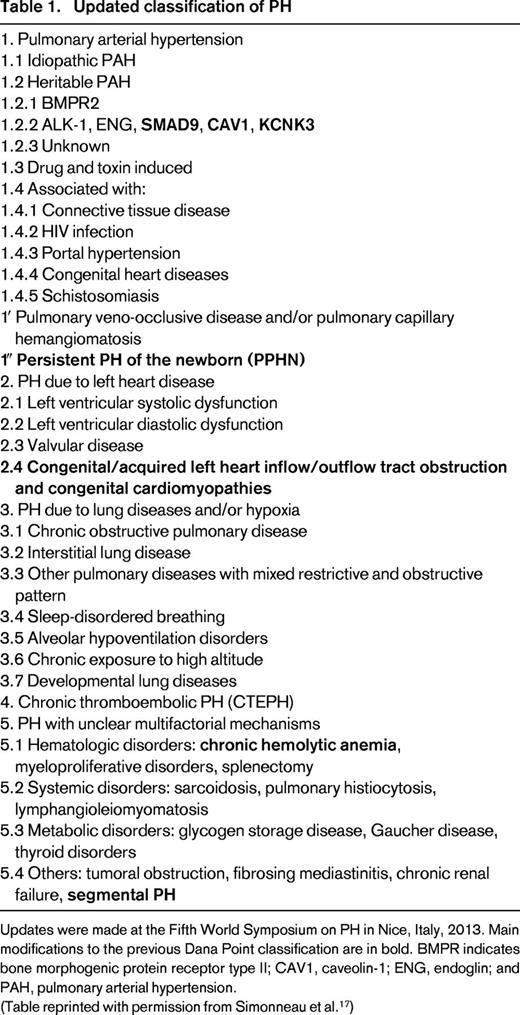

PH is an increasingly recognized vasculopathic complication of SCD.18-21 It is defined as a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mmHg by right heart catheterization (RHC).22 Recently updated classifications of PH have placed PH associated with SCD and other chronic hemolytic anemias within group 5 based upon the significantly different pathological findings and hemodynamic characteristics among patients and an unclear response to pulmonary arterial hypertension-specific therapies17 (Table 1). Three relatively large studies demonstrate that PH confirmed by RHC is common in SCD, with a prevalence of 6%–11%.19-21,23 It has been suggested that the reported prevalence of 6% in the French cohort may have been an underestimate due to the exclusion of 9% of patients with severe renal insufficiency, severe liver disease, and chronic restrictive lung disease.24

Updated classification of PH

Updates were made at the Fifth World Symposium on PH in Nice, Italy, 2013. Main modifications to the previous Dana Point classification are in bold. BMPR indicates bone morphogenic protein receptor type II; CAV1, caveolin-1; ENG, endoglin; and PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

(Table reprinted with permission from Simonneau et al.17 )

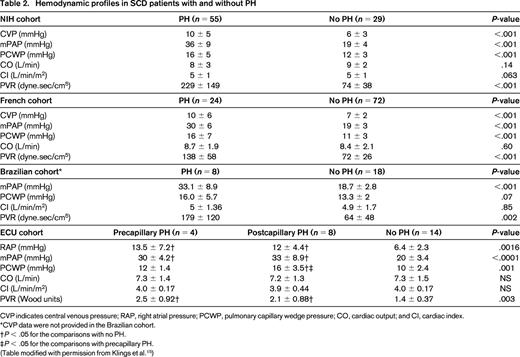

Patients with SCD have a spectrum of hemodynamic findings by RHC (Table 2). Approximately 40% will have features of precapillary PH, defined similarly to other types of group 1 PH: mPAP of ≥25 mmHg with a mean pulmonary artery occlusion (pulmonary capillary wedge) pressure (PAOP) or left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) ≤15 mmHg, and an increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). The PVR is not as high in SCD-related PH compared with other types of group 1 PH because patients with SCD have an increase in cardiac output and a reduction in their blood viscosity due to anemia, resulting in a lower baseline PVR than that observed in nonanemic patients.24 A PVR higher than 2 Wood units or 160 dynes.sec/cm5 is 2 SDs above the mean for SCD patients and is considered to be abnormally high. It has been reported that the PAOP may not accurately reflect the LVEDP obtained during left heart catheterization (LHC) in SCD.23 In this prospective study of 26 SCD patients who underwent simultaneous RHC and LHC, 4 of 8 patients with normal PAOP had elevated LVEDP.23 Although performing simultaneous LHC and RHC may be advantageous in SCD and other patient populations at risk for left ventricular dysfunction, this exposes patients to an additional dye load (RHC does not require contrast) and is not presently the standard of care for evaluation of PH. Postcapillary PH, present to some degree in 50%–60% of SCD patients, is defined as a mPAP ≥25 mmHg and PAOP or LVEDP >15 mmHg. Patients with PH of SCD may have hemodynamics consistent with precapillary PH, postcapillary PH, or features of both.

Hemodynamic profiles in SCD patients with and without PH

CVP indicates central venous pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; CO, cardiac output; and CI, cardiac index.

*CVP data were not provided in the Brazilian cohort.

†P < .05 for the comparisons with no PH.

‡P < .05 for the comparisons with precapillary PH.

(Table modified with permission from Klings et al.15 )

How should patients suspected to have PH be evaluated?

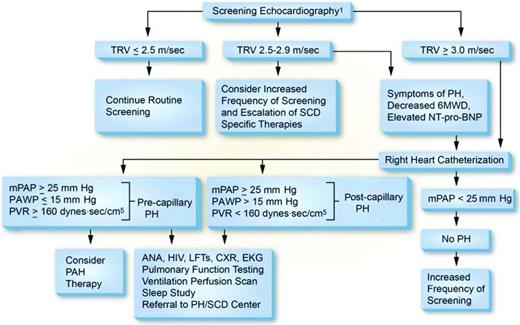

The evaluation of SCD patients suspected to have PH should be similar to that in non-SCD patients. The first part of this evaluation should be a detailed history and physical examination focused on cardiopulmonary signs and symptoms. Most patients with PH will present with progressive exertional dyspnea, particularly with stair climbing and walking up an incline. This may be accompanied by exertional chest pain, light-headedness, or, more ominously, syncope, as well as signs reflective of right-sided heart failure. SCD patients may present a diagnostic conundrum because early symptoms of PH in these patients are nonspecific and may not differ from those experienced by SCD patients without PH.25 Dyspnea is a fairly nonspecific finding in patients with SCD, observed in up to 50% of HbSS and 40% of HbSC adults,26 and often occurs without coexistent PH. However, a history of progressive dyspnea on exertion or limitations of exercise capacity should raise concern for the presence of PH, particularly when observed in conjunction with exertional hypoxemia. Physical findings concerning for PH include exertional hypoxemia, an elevated jugular venous pulse, an accentuated second heart sound (or a fixed splitting of S2), a tricuspid regurgitation murmur, an S3 or S4, a left parasternal lift, a pulsatile liver, hepatomegaly, and peripheral edema. The first test to evaluate patients for PH is a transthoracic echocardiogram. Using the maximum velocity of the regurgitant jet across the tricuspid valve [tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV)], the modified Bernoulli equation can be used to estimate the pulmonary artery systolic pressure as follows: PASP = 4 × (TRV2 + estimated right atrial pressure).27 Although much focus has been placed on using a TRV ≥2.5 m/sec to predict PH and mortality risk in these patients, there are other helpful findings from this study. Echocardiograms can provide an assessment of systolic and diastolic function of the left ventricle, as well as left atrial size, which can be more sensitive for diastolic dysfunction in these patients. Dilation or hypertrophy of the right ventricle and/or enlargement of the right atrium or inferior vena cava can reflect elevated right-sided pressures and, irrespective of the TRV, should raise concern for PH. Abnormal echocardiography should trigger a referral to a cardiologist or pulmonologist with expertise in the management of PH. Regardless of the echocardiographic findings, a RHC is required for the diagnosis of PH. Ancillary tests in this workup include routine laboratory tests such as complete blood counts, electrolytes, renal and liver function tests, and an assessment of hemolysis. Patients should be evaluated for coexistent HIV disease, sarcoidosis, and connective tissue disease (with tests such as antinuclear antibodies) because these conditions could increase their PH risk. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) levels assess right ventricular strain, and levels >160 pg/mL are an independent risk factor for mortality in SCD.28,29 Pulmonary function testing and evaluations for thromboembolic disease (preferably ventilation/perfusion scanning) and sleep-disordered breathing (polysomnography) are recommended in all patients to look for important disease modifiers (Figure 1).

Proposed algorithm for evaluation of PH related to SCD. Echocardiography should be performed while patients are clinically stable. Patients with an mPAP between 20 and 25 mmHg need further study because they may be at increased mortality risk. PAH therapy is to be considered on the basis of a weak recommendation and very low-quality evidence. 6MWD indicates 6-minute walk distance; ANA, antinuclear antibody; CXR, chest X-ray; EKG, electrocardiogram; LFTs, liver function tests; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure. (Reprinted with permission from Klings et al.15 )

Proposed algorithm for evaluation of PH related to SCD. Echocardiography should be performed while patients are clinically stable. Patients with an mPAP between 20 and 25 mmHg need further study because they may be at increased mortality risk. PAH therapy is to be considered on the basis of a weak recommendation and very low-quality evidence. 6MWD indicates 6-minute walk distance; ANA, antinuclear antibody; CXR, chest X-ray; EKG, electrocardiogram; LFTs, liver function tests; PAWP, pulmonary artery wedge pressure. (Reprinted with permission from Klings et al.15 )

Is PH associated with increased mortality in SCD?

Multiple studies show that a TRV of ≥2.5 m/s obtained on Doppler echocardiography is associated with an increased risk of death in adult patients with SCD.11,30,31 In these studies, Doppler echocardiography was performed while patients were in their noncrisis, “steady states.” However, because TRV by itself is not diagnostic of PH, some have questioned whether PH is associated with an increased risk of death in SCD.16 A retrospective study by Castro et al of patients with RHC-confirmed PH reported average systolic, diastolic, and mean pulmonary artery pressures of 54.3, 25.2, and 36.0 mmHg, respectively, in 20 PH patients, compared with values of 30.3, 11.7, and 17.8 mmHg, respectively, in 14 SCD patients without PH.18 Each increase of 10 mmHg in mPAP was associated with a 1.7-fold increase in the rate (hazard ratio) of death (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.7; P = .028). More recent prospective and registry studies confirm the association of RHC-confirmed PH with increased mortality in SCD.19-21 In a prospective multicenter study of 398 SCD patients conducted in France, there was an association between PH and risk of death (12.5% in PH group vs 0.3% in the patients with TRV <2.5 m/s; P = .002).19 When patients with RHC-confirmed PH were compared against those patients with TRV ≥2.5 m/s but without PH on RHC, a nonsignificant trend to a higher mortality rate was observed among patients in the PH group (12.5% vs 1.4%; P = .048). These associations with increased mortality were observed despite the exclusion of patients with severe renal insufficiency, severe liver disease, and chronic restrictive lung disease. A prospective study of 80 SCD patients conducted in Brazil also reported a worse survival in patients with RHC-confirmed PH (P = .0005).20 Finally, in a registry study of 533 patients conducted at the National Institutes of Health, the high risk of death even with moderate elevations of mPAP (median mPAP of 36 mmHg) has been confirmed.21 With a median follow-up of 4.4 years, the mortality rate was significantly higher in the PH group (20 deaths of 56 patients, 36%) than the SCD group, with normal Doppler-echocardiographic estimates of PASP (50 deaths of 477 patients, 13%, P < .0001). In multivariate analysis, measures of pulmonary vascular disease, including pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, pulse pressure, mPAP, transpulmonary gradient, and pulmonary vascular resistance, were associated with risk of death.

How should patients with SCD-associated PH be treated?

In view of the increased mortality associated with PH in SCD, effective treatments are needed. Treatments should preferably be provided by clinicians with expertise in both PH and SCD. In those patients with findings consistent with precapillary PH, treatment with pulmonary arterial hypertension-specific therapies (prostacyclin agonists or endothelin receptor antagonists) should be considered.15 No large randomized, placebo-controlled trials of pulmonary arterial hypertension-specific therapies in SCD have been completed to date. Two parallel placebo-controlled clinical trials of bosentan, a dual endothelin (ET) receptor antagonist, as treatment for precapillary PH (ASSET-1) or postcapillary PH (ASSET-2) were stopped early after the randomization of 14 subjects in ASSET-1 and 12 subjects in ASSET-2 due to the withdrawal of sponsor support.32 Although underpowered to assess efficacy end points, there was no evidence of an increase in adverse events in subjects receiving the study treatment. In a case series of 14 SCD patients (HbSS, n = 12, HbSC, n = 2) with precapillary PH, treatment with either bosentan or ambrisentan (a selective ETA receptor antagonist) resulted in reduced NT-pro-BNP levels suggestive of decreased right ventricular strain, reduced TRVs and improved 6-minute walk distances suggesting improved PH.13 A small, open-label study of sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, in SCD patients with TRV ≥2.5 m/s showed significant improvements in TRV and NT-pro-BNP, as well as increases in 6-minute walk distances.34 All of the study patients underwent intensification of their SCD treatment with hydroxyurea or RBC exchange transfusion before starting treatment with sildenafil. Despite these promising results, a multicenter clinical trial of sildenafil in patients with a TRV ≥2.7 m/s was stopped early due to an increase in significant adverse events, particularly hospitalizations for pain episodes in patients taking sildenafil, leaving the study underpowered to answer the question of efficacy.35 However, because RHC was only obtained in a minority of patients, it is uncertain how many of these patients truly had PH, a severe limitation of this study.

Patients with right-sided heart failure and volume overload are often managed with diuretics and care is required to avoid excessive diuresis, which may not only decrease preload, but may also increase the risk of dehydration in SCD patients. In patients admitted with acute painful episodes, intravenous fluids should also be used judiciously to avoid volume overload.

Aggressive management of SCD has been recommended in patients with PH.15 With the limited treatment options available for these patients, this recommendation is reasonable because of the known association of PH with increased mortality in adult patients.18-21 In addition, pulmonary artery pressures are known to increase during acute painful episodes and acute chest syndrome,36,37 increasing the risk of acute right-sided congestive heart failure and death in those with underlying PH. The risk of death has been reported to be related to the degree of elevation of TRV,37 suggesting that vasoocclusive events need to be prevented in these patients. Although there are conflicting reports of the benefits of hydroxyurea use in patients with an elevated TRV in SCD,11,30,31,38,39 a case series of 5 adult patients with homozygous SCD reported an improvement in TRV after hydroxyurea treatment at the maximum tolerated doses for an average of 14 months.40 There are no studies of hydroxyurea use in SCD patients with RHC-confirmed PH. However, by decreasing hemolysis and the frequency of painful episodes, acute chest syndrome, and mortality associated with sickle cell anemia,41-44 hydroxyurea may be beneficial. Chronic RBC transfusion is effective in decreasing the complications of SCD9,45-47 and may also be beneficial in the treatment of PH. However, there are no peer-reviewed data in this setting and the complications of RBC transfusion therapy should be weighed carefully against any possible benefits of this treatment modality. Although there are no published studies in SCD patients with PH, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been reported to produce a reduction of echocardiographic estimates of pulmonary artery pressure.48

Finally, patients should be evaluated and treated for any coexistent conditions such as thromboembolic disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and hypoxemia, which may worsen the course of their PH.13

Should patients with SCD be screened for PH?

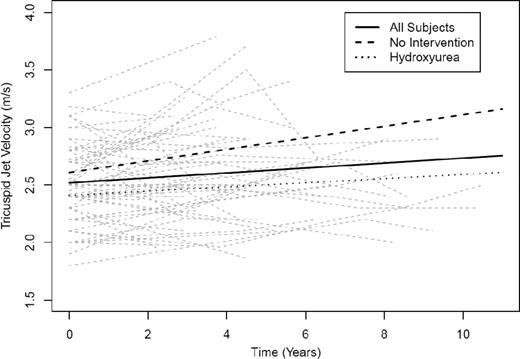

Screening is defined as the presumptive identification of an unrecognized disease or defect by the application of tests, examinations, or other procedures that can be applied rapidly.49 Screening for PH in patients with SCD remains controversial.16,50 To be appropriate for screening, a disease must be serious and have severe consequences, must be progressive so that early treatment is more effective than later treatment, must have a preclinical phase that can be identified by a screening test, and must have a preclinical phase that is fairly long and prevalent in the target population.49 There is abundant evidence that echocardiography-derived TRV ≥2.5 m/s, as well as PH confirmed on RHC, are associated with an increased risk of death in adult patients with SCD,11,18-21,30,31 confirming the serious nature of these pulmonary vasculopathies. The consequences of increased TRV and PH are much less certain in children with SCD. There is no reported association of elevated TRV with increased mortality in children,51-55 possibly due to the overall low mortality rate in children with SCD.56 However, an elevated baseline TRV has been shown to be associated with an ∼4-fold increase in the odds of a 10% or greater decline in 6-minute walk distance after 22 months of follow-up (95% confidence interval, 1.3-14.5; P = .015).55 There are limited data on whether PH is progressive in SCD. However, a single-center prospective study of 55 adult patients followed for a median of 4.5 years (range, 1.0-10.5) reported an increase in TRV in 31 patients, whereas 24 patients showed no increase in TRV.57 A linear mixed-effects model indicated an overall rate of increase in the TRV of 0.02 m/s per year (P =.023; Figure 2). Despite the overall slow rate of increase in the TRV, 6 of 31 patients with an increase in TRV died, compared with 1 of 24 patients with no increase in the TRV, although the difference did not achieve statistical significance (P = .09, log-rank test). Elevated TRV obtained on Doppler echocardiography is common in patients with SCD,11,31,33,38,52 and mild TRV elevations appear to represent the preclinical phase of PH.

Change in TRV over time in all subjects. Shown are subjects with no intervention (—) and subjects on hydroxyurea (….). At baseline, all patients have an estimated TRV of 2.5 m/s, with an estimated rate of increase of 0.02 m/s per year. (Reprinted with permission from Desai et al.57 )

Change in TRV over time in all subjects. Shown are subjects with no intervention (—) and subjects on hydroxyurea (….). At baseline, all patients have an estimated TRV of 2.5 m/s, with an estimated rate of increase of 0.02 m/s per year. (Reprinted with permission from Desai et al.57 )

Doppler echocardiography is a noninvasive screening test for PH. Recent studies have evaluated the validity and predictive value of echocardiographic estimates of PASP with those obtained during RHC.19,23,58 In a retrospective study of 25 SCD patients with TRV ≥2.5 m/s who underwent RHC, the sensitivity and specificity of a TRV of 2.51 m/s were 77.8% and 18.8%, respectively.58 When TRV cutoffs of 2.8 m/s and 2.88 m/s were used, the sensitivity and specificity for both cutoff values were 67% and 81%, respectively. Using a TRV of at least 2.5 m/s as a cutoff value for the selection of patients for RHC, the positive predictive value (PPV) of echocardiography for the detection of PH in a multicenter cohort was 25% (24 of 96 patients).19 However, this low PPV was likely influenced by the exclusion of 9% of the population (patients with severe kidney disease, liver disease, and restrictive lung disease) at high risk for PH. When a TRV cutoff value of at least 2.9 m/s was used for the selection of patients for RHC, the PPV of echocardiography was increased from 25% to 64%, although the false-negative rate with this higher cutoff value was at least 42%. An exploratory analysis using a combination of TRV between 2.5 and 2.8 m/s, NT-pro-BNP level of at least 164.5 pg/mL, and 6-minute walk distance of <333 m resulted in an even higher PPV of 62%. Finally, using a TRV of at least 2.5 m/s as a cutoff value for the selection of patients for RHC, a smaller study reported a PPV of 46% (12 of 26 patients).23 Although NT-pro-BNP levels of at least 160 pg/mL have been shown to be associated with increased mortality in SCD,28,29 the utility of assessing NT-pro-BNP alone as a screening tool for PH has not been studied in SCD and this test should not be used in isolation.

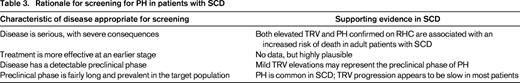

Despite the limited data on treatment of PH in SCD, screening appears to be appropriate because of the prevalence of this condition, its serious nature, the likelihood of progression, and the ability to identify a preclinical phase (Table 3).

Conclusion and future directions

Although there are multiple studies evaluating Doppler echocardiography in SCD, studies of RHC-confirmed PH are limited. Based on the currently available evidence, we conclude the following: PH is common in SCD and is associated with an increased risk of death in adult patients. The prevalence of PH in children with SCD is uncertain. Patients suspected to have PH based on the results of Doppler echocardiography or other evaluation should always have the diagnosis confirmed by a RHC, with evaluation of hemodynamic parameters. Although data on treatment of PH in SCD are limited, we recommend optimization of SCD therapy. In patients with precapillary PH based on RHC, pulmonary arterial hypertension-specific therapies, including endothelin-receptor antagonists and prostacyclin agonists, should be considered. In patients with precapillary PH, we recommend against phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy as frontline treatment because of the increased incidence of painful episodes. Other coexistent clinical conditions that may worsen the course of PH should be treated as required.

Despite the limited available treatment options, we recommend routine screening of adult patients with Doppler echocardiography, perhaps in combination with NT-pro-BNP measurements and assessment of 6-minute walk distances. The frequency of screening remains undefined. Although the recently published clinical practice guidelines suggested obtaining an echocardiogram every 1-3 years,15 patients with TRV values <2.5 m/s may not need to be screened more frequently than every 5 years. Patients with TRV values between 2.5 and 2.9 m/s should be screened more frequently. Patients with TRV values ≥3.0 m/s should have an RHC to confirm the presence of PH. Patients with cardiopulmonary symptoms should undergo a complete evaluation for PH.

Although some of these recommendations are likely to be controversial, we believe that they represent the current state of the literature. Given the high prevalence of pulmonary vasculopathic complications in SCD, additional studies are required to answer several important questions. More studies are required to define the best screening tools for PH and the optimum frequency of screening in SCD. Ultimately, the clinically important question is whether screening with Doppler echocardiography, possibly in combination with other tools, decreases mortality from PH. Finally, continued research is required to define the optimum treatment for these patients.

Acknowledgments

K.I.A. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01 HL111659 and U01 HL117659 and an award from the North Carolina State Sickle Cell Program. E.S.K. is supported by NIH grants R21 HL107993-01, R01AT006358, and CDRN-1306-04608.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: K.I.A. is on the board of directors or an advisory committee for Adventrx Pharmaceuticals, HemaQuest Pharmaceuticals, Sangart, and Selexys Pharmaceuticals; has received research funding from HemaQuest Pharmaceuticals and Selexys Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Pfizer and Celgene; and has received honoraria from Pfizer, Adventrx Pharmaceuticals, HemaQuest Pharmaceuticals, and Selexys Pharmaceuticals. E.S.K. has consulted for Pfizer. Off-label drug use: Prostacyclins and endothelin receptor antagonists as treatment for PH in SCD.

Correspondence

Kenneth I. Ataga, MBBS, Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Physicians' Office Bldg., 3rd Floor, CB# 7305, 170 Manning Dr., Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7305; Phone: (919)843-7708; Fax: (919)966-6735; e-mail: kataga@med.unc.edu.