Abstract

For the last 20 years, high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) for multiple myeloma has been considered a standard frontline treatment for younger patients with adequate organ function. With the introduction of novel agents, specifically thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide, the role of ASCT has changed in several ways. First, novel agents have been incorporated successfully as induction regimens, increasing the response rate before ASCT, and are now being used as part of both consolidation and maintenance with the goal of extending progression-free and overall survival. These approaches have shown considerable promise with significant improvements in outcome. Furthermore, the efficacy of novel therapeutics has also led to the investigation of these agents upfront without the immediate application of ASCT, and compelling preliminary results have been reported. Next-generation novel agents and the use of monoclonal antibodies have raised the possibility of not only successful salvage strategies to facilitate delayed transplantation for younger patients, but also the prospect of an nontransplantation approach achieving the same outcome. Moreover, this could be achieved without incurring acute toxicity or long-term complications that are inherent to high-dose alkylation, and melphalan exposure in particular. At present, the role of ASCT has therefore become an area of debate: should it be used upfront in all eligible patients, or should it be used as a salvage treatment at the time of progression for patients achieving a high quality of response with initial therapy? There is a clear need to derive a consensus that is useful for clinicians considering both protocol-directed and non-protocol-directed options for their patients. Participation in ongoing prospective randomized trials is considered vital. While preliminary randomized data from studies in Europe favor early ASCT with novel agents, differences in both agents and the combinations used, as well as limited information on overall survival and benefit for specific patient subsets, suggest that one size does not fit all. Specifically, the optimal approach to treatment of younger patients eligible for ASCT remains a key area for further research. A rigid approach to its use outside of a clinical study is difficult to justify and participation in prospective studies should be a priority.

Learning Objective

To understand that research into the timing and role of ASCT is essential because the impact of both first-generation and second-generation novel agents, as well as other immunotherapeutic strategies including monoclonal antibodies, continue to improve patient outcome in MM

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is neoplastic proliferation of monoclonal plasma cells that is typically restricted to the BM, with common clinical features including renal dysfunction, anemia, hypercalcemia, and involvement of cortical bone, usually manifest as lytic lesions.1 Recent advances in our understanding of disease biology have established the extraordinarily diverse clonal heterogeneity of this otherwise incurable hematologic malignancy, not only between patients but also within patients in whom clonal evolution appears to occur during the course of their disease.2,3 The critical nature of the tumor microenvironment in our understanding of disease biology and the complex genetics that underpin its pathogenesis have helped to better characterize the complexity of the illness.1-4 Over the same time period, treatment options have expanded dramatically and the therapies available to patients are now both numerous and more effective with the use of biologically derived novel agents.1 During the 1990s, autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) emerged as a standard of care in younger, transplantation-eligible patients by virtue of improved response rate and progression-free survival (PFS), with the feasibility of administering high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell support then being well established.1

In the era of novel therapies, the treatment landscape and prognosis have changed, with the median survival improving to between 7 and10 years and multiple treatment options becoming available to patients across all age groups.1,6 This has led clinicians to suggest that MM can be managed without high-dose therapy as a requirement in all eligible cases and that it can still be converted into a chronic illness in selected patients without the attendant toxicity and long-term risks of ASCT (such as secondary leukemia). Moreover, risk-adapted strategies tailored to biological parameters guiding treatment decisions in daily practice have become more commonly applied.4 Therefore, the view that high-dose therapy with ASCT should be used in all younger patients as the standard of care is now increasingly challenged, particularly in the United States, where studies in fact suggest that only a small proportion of newly diagnosed MM patients undergo ASCT as part of their upfront therapy for MM.5 Specifically, opting to keep ASCT in reserve in selected patients and to use ASCT as a salvage approach for patients preferring not to pursue high-dose therapy as part of their initial treatment is common.7,8 At present, it is appropriate to collect stem cells initially after successful induction and store these for younger patients who do not wish to proceed immediately to ASCT, recognizing that this is an important mainstay for future treatment.7,8 This does constitute an important resource question, and this may explain in part why this approach has been less popular in Europe.9 Overall, substantial questions remain as to who is best served by ASCT and when the modality can be best applied, and this is a key focus of ongoing randomized trials.8-10

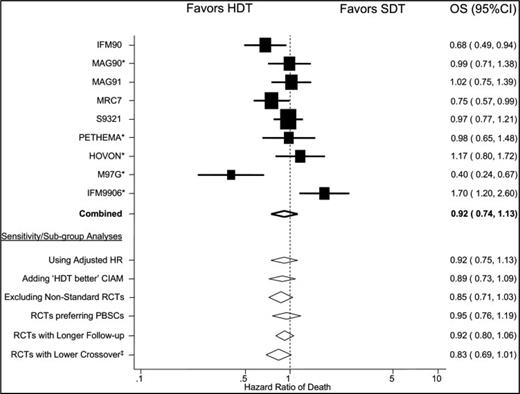

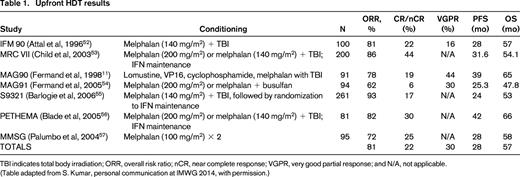

ASCT before the advent of novel agents

ASCT supporting high-dose chemotherapy (typically using melphalan, first in combination with total body radiation and then as a single agent) was established as a standard of care by a series of randomized trials conducted in the 1990s.9,10 These demonstrated PFS and overall response advantages to transplantation compared with controls but, interestingly, the overall survival (OS) benefit was less clear (Table 1). Indeed, a study by Fermand et al with conventional treatment (ie, before the era of novel therapies) showed PFS and quality of life advantage, but not survival benefit, when they compared early with late ASCT in newly diagnosed MM patients.11 An important meta-analysis conducted by Koreth et al is particularly informative in this context.12 Although the PFS benefit was apparent, the OS benefit was only marginal.12 Very interestingly, particular subgroups in whom the benefit of early versus late ASCT could be demonstrated were in favor of those studies in which late ASCT was not performed in a substantial proportion of the participants. This suggests that the feasibility of successful salvage followed by delayed ASCT is a key metric for equipoise in assessing any benefit (Figure 1). Before the use of novel therapies, effective salvage options after initial treatment failure were both fewer and less effective than now, implying that this change in the treatment landscape may be of particular importance going forward.

Upfront HDT results

TBI indicates total body irradiation; ORR, overall risk ratio; nCR, near complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; and N/A, not applicable.

(Table adapted from S. Kumar, personal communication at IMWG 2014, with permission.)

OS: meta-analysis. (Figure reprinted with permission from Koreth et al.12 )

Changing role of ASCT with the incorporation of novel agents

The incorporation of novel agents into ASCT has seen the improvement of induction regimens with the integration of proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory drug (IMiD)–based therapy and the successful development of combination therapies as induction, consolidation, and maintenance. Randomized trials have shown clinical benefit to this approach in several different settings.13,14 What is particularly important is that the use of proteasome inhibition has been shown to be critical in improving response, PFS, and OS benefit as an induction strategy in a series of meta-analyses.15 Therefore, the integration of novel therapies into the treatment paradigm of ASCT in MM appears to have improved outcome substantially.16

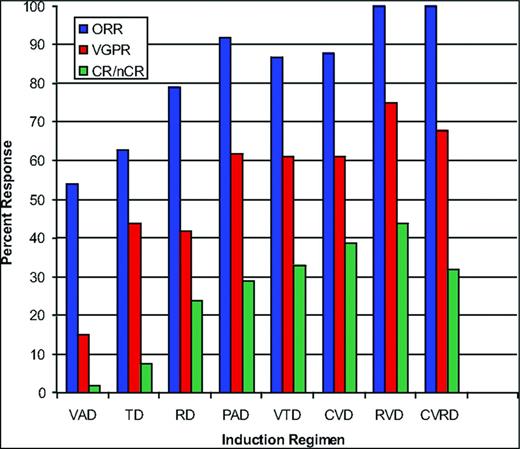

Best induction regimens in the novel agent era with the integration of consolidation and maintenance

Best induction regimens in the novel agent era appear to be those that contain at least 3 drugs or more and, in this context, the combination of proteasome inhibition and immunomodulation has been vital17 (Figure 2). The preclinical synergy demonstrated by this platform has been clinically validated in several settings, first with VTD (bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone), then RVD (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone), and CRD (carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone), and, most recently, with RID (ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone). The latter is the first all oral regimen in which the highly consistent and remarkable efficacy of this combinatorial induction strategy has been demonstrated.14,17-21

Combinations in the upfront treatment of MM. (Research originally published in Stewart et al.7 )

Combinations in the upfront treatment of MM. (Research originally published in Stewart et al.7 )

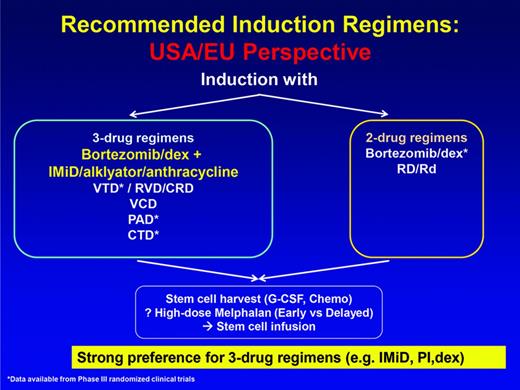

At this point, therefore, 3-drug regimens in which proteasome inhibition and an IMiD are combined are considered the current best standard induction for ASCT-eligible patients (Figure 3). The addition of conventional agents to this platform has been associated with improvements in response rates, but no convincing improvement in clinical benefit either in the context of cross-trial comparisons or randomized phase 2 trials.22

Recommended induction regimens: US/EU perspective. (Figure modified with permission from Ludwig et al.51 )

Recommended induction regimens: US/EU perspective. (Figure modified with permission from Ludwig et al.51 )

Several studies have shown improvements in outcome using consolidation regimens with either proteasome inhibition alone or in combination with IMiDs to further enhance clinical benefit.23,24 Importantly, the use of maintenance, particularly until progression, has now demonstrated both PFS and OS benefit in 2 of 3 major randomized phase 3 studies post ASCT.25-28

From these encouraging data has emerged a critical question regarding the role of ASCT as a required component of the therapeutic paradigm. The depth, quality, and durability of response seen from these 3 drug platforms, as well as the integration of consolidation and maintenance strategies with or without ASCT, has become an area of active research. Given both the acute and also the well-recognized long-term toxicities of ASCT, which include the important but relatively uncommon complication of secondary leukemia, the role of ASCT needs to be reevaluated given the success of novel agent combination approaches, and not only as part of initial therapy but also as part of salvage.

Recent randomized data using IMiD-based therapy alone has shown significant PFS and a trend for OS benefit with ASCT but critically these studies have not included proteasome inhibition.27,28 Furthermore, although some aspects of the studies are compelling (not least that maintenance until progression appears to be important in both the non-ASCT and ASCT arms), these trials were limited in size for phase 3 studies incorporating 2 randomizations (specifically early vs late ASCT, as well as maintenance vs control).27,28 Therefore, the trials may be relatively underpowered in terms of their ability to distinguish subsets of patients who may or may not benefit from early versus late ASCT.

Interestingly, other recent retrospective studies of both IMiD and proteasome inhibitor–based combinations in the setting of early or late ASCT suggest no benefit to early ASCT on outcome—or at least no difference.17,29,30 Given the striking efficacy of RVD [with overall response rates of 100% and near complete or complete remission (CR) rates of 52% seen in phase 2 populations] and the remarkable results of CRD, with 63% near CR or better reported, randomized studies incorporating both proteasome inhibition and prolonged maintenance are obviously key.18,31

Impact of second-generation novel agents and monoclonal antibodies and advances in immunotherapy

As the success of first-generation novel agents and their integration into the standard therapeutic paradigm for the treatment of MM has now become well established, critical next steps have been the evolution of second-generation novel agents and the advent of monoclonal antibodies, with the latter in particular revolutionizing the field. Unprecedented qualities of response and preliminary results suggesting an ability to overdrive mutational genetics with responses that are durable are being seen with CD38-targeting antibodies used in combination and as monotherapy, as well as with elotuzumab, which targets SLAMF7 (previously known as CS1).32-35 Results in combination have been especially promising with elotuzumab in terms of PFS benefit, and early data with daratumumab and then SAR650984 have been considered worthy of breakthrough status.32-35 In addition, next-generation novel agents include highly potent second-generation proteasome inhibitors such as carfilzomib and ixazomib, as well as others in earlier phase drug development, including marizomib and oprozomib.36 Moreover, the remarkable impact of the third-generation IMiD pomalidomide has also shown the ability to overdrive thalidomide, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and carfilzomib failure, both when these agents have been used alone and when they have been used in combination.37 Other small-molecule inhibitors are in development, with some currently under consideration for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (such as the pan-deacetylase inhibitor panabinostat) based upon strong evidence of efficacy, which is further expanding the therapeutic armamentarium, with other agents such as ricolinostat in the same class showing promise.38-40 Therefore, potent salvage regimens now exist and/or are in development for patients in whom frontline initial therapy followed by consolidation and maintenance but without early ASCT have exhausted benefit. These offer reliable rates and durations of response that make the ability to then move to a delayed ASCT more feasible. In addition, by bringing these highly active agents earlier into the treatment of MM, the utility of ASCT for all patients, versus subsets of patients, becomes an increasingly prescient question and also raises the important challenge of whether these approaches will in fact be better in patients relapsing without prior ASCT, versus not. Finally, recent advances in immunotherapy, and in particular the emergence of checkpoint inhibitors, vaccines, and cellular therapies, bring forward the opportunity for a whole new paradigm of treatment in which the reset of a patient's immunological repertoire could be achieved without high-dose alkylation and ASCT.41,42

Advances in disease biology and risk-adapted treatment

In parallel to the advances in therapeutics in MM, the dissection of the complex genomics and proteomics of the disease has substantially affected our understanding of its molecular biology, further improving our ability to estimate prognosis and assess risk. This is moving beyond the original staging systems of Durie-Salmon and the International Staging System, as well as cytogenetics and FISH.43 Moreover, risk-adapted strategies tailored to biological parameters guiding treatment decisions in daily practice have become more commonly applied, fundamentally challenging the prerequisite that ASCT should be considered as a broadly uniform treatment approach.4,43 Gene expression profiling and other forms of array technology continue to advance.4 In addition, imaging techniques and the ability to define minimal residual disease and to confirm stringent complete response continue to evolve.44-46 In aggregate, such correlative approaches to patient management should further enhance and refine the capacity to tailor therapy and so further reduce tumor burden and optimally target biology to improve patient outcome.

Future role of ASCT and the imperative of continued research and participation in randomized trials

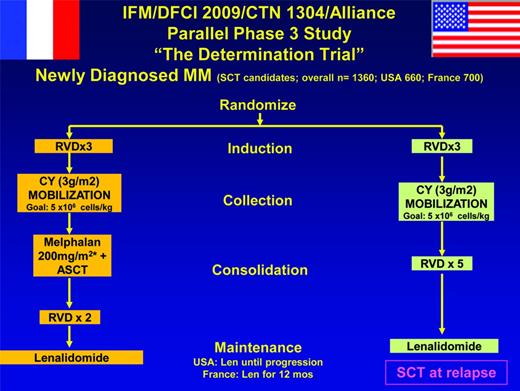

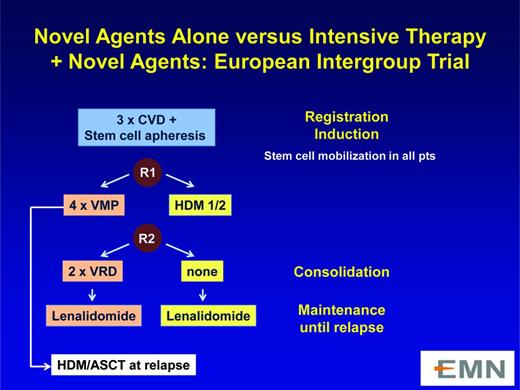

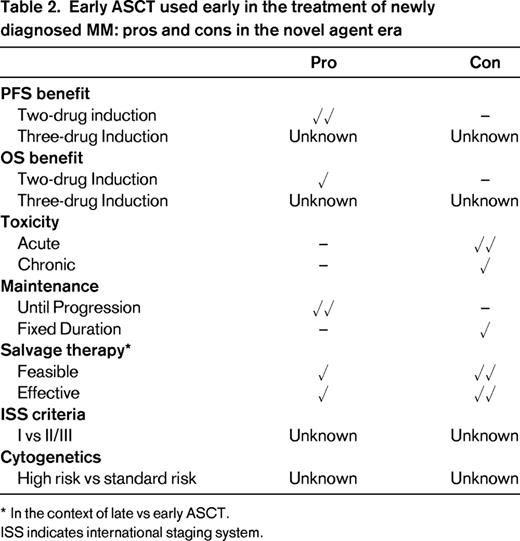

Research into the timing and role of ASCT is essential because the impact of both first-generation and second-generation novel agents and other immunotherapeutic strategies (including monoclonal antibodies and cellular therapies) continue to improve patient outcome in MM and promise more durable clinical benefit.47,48 Excitingly, treatments targeting mutational drivers (vs plasma cell biology alone) are yielding long-term stability. Moreover, the ability to better classify disease at the molecular level and so prognosticate more informatively and to better define minimal residual disease are complementing these advances.4,43-46 Therefore, the optimal approach to the treatment of younger patients eligible for ASCT remains a key area for further research (Figures 4, 5).49 A rigid approach to its use outside of clinical studies is difficult to justify.50 Although the importance of response to initial therapy, the ability to collect and store stem cells (so allowing flexibility in timing), and the benefits of continuous therapy are now increasingly apparent, participation in randomized prospective trials has to be the priority as the treatment paradigm continues to evolve, and important unanswered questions remain (Table 2).

“The Determination Trial.” This trial is described at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01208662.

“The Determination Trial.” This trial is described at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01208662.

Novel agents alone versus intensive therapy plus novel agents: aEuropean Intergroup trial. This trial is described at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01208766.

Novel agents alone versus intensive therapy plus novel agents: aEuropean Intergroup trial. This trial is described at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01208766.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the R.J. Corman Multiple Myeloma Research Fund. The authors gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contribution of Michelle Maglio in the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: P.G.R. serves on advisory committees for Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Johnson & Johnson, Millennium, and Genmab. J.P.L. has received research funding from Onyx, Novartis, Millennium, and Celgene. N.C.M. is a consultant for Celgene, Onyx, Janssen, Sanofi-Avantis, and Oncopep and has equity ownership of and patents/royalties with Oncopep. K.C.A. is a consultant for Celgene, Onyx, Millennium, Gilead, Sanofi-Adventis, and BMS and is a founder and has equity ownership of Oncopep and Acetylon.

Correspondence

Paul G. Richardson, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, MA 02215; Phone: (617)632-2104; Fax: (617)632-6624; e-mail: paul_richardson@dfci.harvard.edu.