Abstract

A 55-year-old man presented with splenomegaly (10 cm below left costal margin) and leucocytosis (145 × 109/L). Differential showed neutrophilia with increased basophils (2%), eosinophils (1.5%), and left shift including myeloblasts (3%). A diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase was established after marrow cytogenetics demonstrated the Philadelphia chromosome. Molecular studies showed a BCR-ABL1 qPCR result of 65% on the International Scale. Imatinib therapy at 400 mg daily was initiated due to patient preference, with achievement of complete hematological response after 4 weeks of therapy. BCR-ABL1 at 1 and 3 months after starting therapy was 37% and 13%, respectively (all reported on International Scale). Is this considered an adequate molecular response?

Learning Objective

To be aware of the importance of early response monitoring for CML-CP patients treated with TKI therapy and implications for long-term outcomes.

Discussion

With tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the majority of chronic phase myeloid leukemia (CML) patients enjoy excellent overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival.1 Many achieve significant reduction in disease burden quantified by rapid and deep qPCR responses. Although treatment-free remission is currently only possible for highly selected patients within clinical trial confines, in the future this may become the treatment goal for patients with good-risk disease.2 However, some patients still progress to accelerated phase or blast crisis. A strategy to promptly identify patients truly requiring additional therapy is among the top priorities for CML research.

Recent reports have suggested that long-term outcomes with TKI therapy can be predicted based on very early responses (at 3 or 6 months), identifying patients with a heightened risk of progression. Either cytogenetic response or molecular response assessed via qPCR, may be used. In this chapter, we examine the prognostic significance of achieving an early molecular response (EMR), as defined by BCR-ABL1 ≤10% at 3 months, a milestone recommended by both the European Leukemia Net (ELN)3 and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)4 . All BCR-ABL1 values quoted herein are interpreted on the International Scale (IS).

A literature search was done using PubMed, limited to articles in English, excluding case reports and reviews. We limited our search to articles published after 2006, when standardization of BCR-ABL1 results on the IS became applicable.5,6 A search using the following terms: (“BCR-ABL” or “BCR-ABL1”) and (“3 months” or “3 month”) and (“chronic myeloid leukemia” or “CML”) yielded 80 articles. A separate search with (“early molecular response” or “early response” or “early responses” or “early molecular responses”) and (“chronic myeloid leukemia” or “CML”) yielded a further 22 articles. After reviewing the abstracts, 16 articles7-22 were included for this analysis. Five additional references were included from bibliographies.23-27

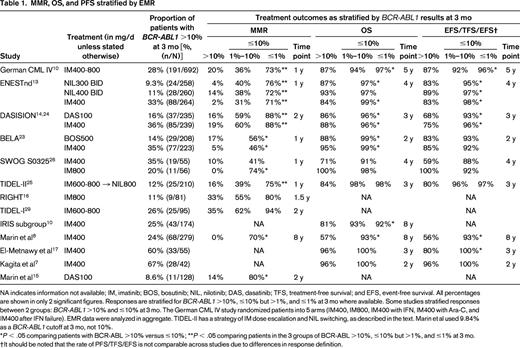

Table 1 summarizes 12 studies that reported the rate of EMR and associated survival outcomes. The correlation between EMR and major molecular response (MMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤0.1%) at 12 months is included where available. Five other studies12,18,19,21,27 were examined, which reported results in formats not easily incorporated into the table and are therefore not listed.

MMR, OS, and PFS stratified by EMR

NA indicates information not available; IM, imatinib; BOS, bosutinib; NIL, nilotinib; DAS, dasatinib; TFS, treatment-free survival; and EFS, event-free survival. All percentages are shown in only 2 significant figures. Responses are stratified for BCR-ABL1 >10%, ≤10% but >1%, and ≤1% at 3 mo where available. Some studies stratified responses between 2 groups: BCR-ABL1 >10% and ≤10% at 3 mo. The German CML IV study randomized patients into 5 arms (IM400, IM800, IM400 with IFN, IM400 with Ara-C, and IM400 after IFN failure). EMR data were analyzed in aggregate. TIDEL-II has a strategy of IM dose escalation and NIL switching, as described in the text. Marin et al used 9.84% as a BCR-ABL1 cutoff at 3 mo, not 10%.

*P < .05 comparing patients with BCR-ABL >10% versus ≤10%; **P < .05 comparing patients in the 3 groups of BCR-ABL >10%, ≤10% but >1%, and ≤1% at 3 mo.

†It should be noted that the rate of PFS/TFS/EFS is not comparable across studies due to differences in response definition.

EMR achievement is associated with superior overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in 15 of the 16 studies examined. EMR is also associated with increased probability of achieving MMR and deep molecular responses, such as MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1 ≤0.0032%, 4.5 log reduction). For example, the probability of MR4.5 achievement in the ENESTnd study (300 mg BID arm) was 50% by 3 years in patients with BCR-ABL1 ≤1% at 3 months versus only 4% in patients with EMR failure.13 The same pattern is seen in patients treated with other TKIs and in other cohorts.8,12,21,28

The number of patients failing to achieve EMR varies across studies and is highest when imatinib 400 mg daily is used as frontline therapy. In contrast to standard dose, patients starting imatinib frontline at higher doses (600-800 mg daily) have improved EMR achievement rates (TIDEL-I/II,25,29 RIGHT,16 and SWOG S032526 ). Patients receiving second-generation TKIs upfront in the ENESTnd,13 DASISION,14 and BELA23 studies also have a high probability of achieving EMR.

Clinical risk scores are of value in predicting patients at higher risk of EMR failure. In the nilotinib 300 mg BID arm of the ENESTnd study, 14% versus 7% of high versus low Sokal risk patients failed to achieve EMR. This difference is even more marked in the imatinib arm: 56% versus 21% of high versus low Sokal risk patients failed to achieve EMR.13 In the German CML IV study, 43% of high EUTOS score patients failed to achieve EMR compared with 26% of low EUTOS score patients.10

Not all patients with EMR failure fare poorly, and scrutiny of baseline and 6-month BCR-ABL1 values may further segregate patients into discrete risk groups. In an Ontario cohort, patients who failed to achieve EMR at 3 months but had subsequent reductions in BCR-ABL1 to ≤10% at 6 months had OS and PFS that approached patients who achieved EMR. In contrast, patients who had BCR-ABL1 ≥10% at both 3 and 6 months were at particularly high risk of disease transformation.30 Kinetics of the individualized molecular response may also yield additional information. For example, the Adelaide group evaluated BCR-ABL1 values over a patient's first 3 months of imatinib treatment and calculated the period of time needed for BCR-ABL1 to be reduced by 50%. Patients failing to achieve EMR but with a “halving time” of <76 days have a lower risk of treatment failure compared with patients with 50% reduction at >76 days.11 The German CML IV study group arrived at a similar conclusion by examining the prognostic significance associated with an individual's velocity of BCR-ABL1 decline.9

The current NCCN guidelines recommend changing TKIs (or increasing imatinib dose to 800 mg for those who started at 400 mg frontline) for patients failing to achieve BCR-ABL1 ≤10% IS at 3 months.4 However, evidence demonstrating benefit of such intervention is scant. The LASOR study found that switching patients with no cytogenetic response at 3 months to nilotinib resulted in a higher MMR rate at 12 months compared with continuation of imatinib.31 TIDEL-II examined this question in a single-arm, phase 2 study (N = 210). Patients with EMR failure (25 of 210) either received dose-escalated imatinib 800 mg daily or were switched to nilotinib 400 mg BID, resulting in an MMR rate at 12 months of 16%.25 The CA 180-399 study is currently open and randomizes patients who fail to achieve EMR on imatinib 400 mg daily to either continuing imatinib or switching to dasatinib. Results from this study are expected shortly (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier #NCT01593254).

Our review does not explicitly address the prognostic significance of the molecular response at 6 months or that of early cytogenetic response. In brief, there is a good concordance between prognostic significance of the BCR-ABL1 value at 3 and 6 months, as patients with BCR-ABL1 ≥10% IS at 6 months also experience inferior OS and PFS.8,10,13,14,19,30 Further evidence of the benefit in switching therapy based on molecular response at 3 months (very early switch) versus 6 months (early switch) or whether it is detrimental to delay interventions until correlative 3- and 6-month data are available are expected in forthcoming trials. Early cytogenetic responses (Philadelphia chromosome-positive metaphases ≤35% by 3 months and 0% by 6 months) are similarly associated with superior OS and PFS and parallel the molecular response data.10,14,19 In addition, EMR achievement is associated with improved long-term outcome in second-line treatment with either nilotinib or dasatinib after imatinib failure.32,33

Recommendations

Our patient had a high Sokal risk score and consequently had a higher risk of failing to achieve EMR. Such patients should be treated with second-generation TKIs upfront (GRADE 2A).34 All patients should have molecular monitoring when available, especially at baseline and at 3 months (GRADE 1A). For patients with BCR-ABL1 >10% IS at 3 months, therapeutic interventions including TKI switch should be considered (GRADE 2C). Our patient switched therapy from imatinib to nilotinib at 3 months and had BCR-ABL1 values of 2.8% and 0.52% at 9 and 12 months, respectively. He went on to achieve MMR at 24 months.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: D.T.Y. has received scholarship funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the A.R. Clarkson Foundation and has consulted for, served on the board of directors or an advisory committee for, or has received research funding and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis. M.J.M. has consulted for Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Pfizer. Off-label drug use: none disclosed.

Correspondence

Michael J. Mauro, MD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, Box 489, New York, NY 10065; Phone: (212)639-3107; Fax: (212)772-8550; e-mail: maurom@mskcc.org.