Abstract

In the past 50 years, the lifespan of an individual affected with severe hemophilia A has increased from a mere 20 years to near that of the general unaffected population. These advances are the result of and parallel advances in the development and manufacture of replacement therapies. We are now poised to witness further technologic leaps with the development of longer-lasting replacement therapies, some of which are likely to be approved for market shortly. Prophylactic therapy is currently the standard of care for young children with severe hemophilia A, yet requires frequent infusion to achieve optimal results. Longer-lasting products will transform our ability to deliver prophylaxis, especially in very young children. Longer-lasting replacement therapies will require changes to our current treatment plans including those for acute bleeding, prophylaxis, surgical interventions, and even perhaps immunotolerance induction. Ongoing observation will be required to determine the full clinical impact of this new class of products.

Background

Before the advent of efficient replacement therapy, the life expectancy of a child with severe hemophilia A was approximately 20 years.1,2 Currently, the life expectancy of this population is near that of the general unaffected population2,3 —a major achievement unparalleled in other chronic genetic conditions. The first recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) concentrates were approved in the United States in 1992.4 rFVIII concentrates have improved the product supply, decreased to near zero viral bloodborne infections, and allowed the development of prophylactic treatment regimens. Now, 21 years later, a new class of rFVIII concentrates are emerging that will allow us to challenge our current treatment regimens and paradigms of care. Sequelae of hemophilia include musculoskeletal complications, development of inhibitory antibodies, and transmission of viral bloodborne infections.5,6 Uncontrolled or unrecognized major bleeding events may have severe consequences, including local functional deficits, hemorrhagic shock, neurocognitive defects, and death.7,8 These significant events may be minimized by the use of prophylactic treatment regimens.9

Prophylactic treatment regimens achieve a less severe deficiency based upon nadir FVIIII levels accomplished with regularly scheduled infusions. Treatment regimens to achieve optimal bleed suppression and prevention vary individually; some patients tolerate nadir levels ≤1%, whereas others require higher nadir levels to achieve the desired therapeutic outcome.10,11 Current standard prophylactic regimens commonly use infusion therapy administered 3 times weekly, whereas other regimens require every other day administration; regimens are individually modified to achieve optimal bleed suppression yet tailored to the patient's age and individual and family needs.

Chief among the associated issues with current regimens is the need for adequate venous access and patient/family compliance. These issues are magnified in the very young pediatric population, in whom central venous access devices (CVADs) have been used to overcome technical difficulties. Although CVADs make prophylaxis feasible in young children, they are associated with complications, most notably mechanical failure including fracture, dehiscence of the skin over the reservoir, infection, and thrombosis. Once placed and used, families may have difficulty with CVAD removal and transition to peripheral venous access.12

Adherence to demanding therapeutic regimens that include frequent morning infusion to achieve adequate hemostatic coverage during periods of highest activity make these regimens less effective and compromise their cost-benefit ratio.13 In addition, significant healthcare provider efforts are required to ensure adequate comprehension of the rationale for and requirements of the therapeutic plan, follow-up to detect compliance barriers, and development of agreed-upon solutions to overcome identified issues.

As children progress into adolescence, adherence is often further compromised.14 Decreased frequency of required infusion and the achievement of higher trough levels could affect this age group's ability to fully use and adhere to therapeutic regimens and achieve improved outcomes. In addition, the use of prophylactic regimens have therapeutic advantages even in adults with prior musculoskeletal sequelae including decreased numbers of acute hemorrhagic episodes, slowed progression of joint disease in previously affected areas, prevention of joint disease in previously unaffected areas, and improved quality of life and productivity.15,16 The use of prophylaxis in adults with severe hemophilia A is inconsistent and not standardized. The advent of longer-acting products may increase the likelihood that affected adults choose this therapeutic option and enjoy improved outcomes.

The development of inhibitory alloantibodies (inhibitors) occurs in ∼ 25% to 30% of severe hemophilia A patients and in 3% to 13% of those with moderate or mild disease.17,18 Inhibitors neutralize infused FVIII and therefore greatly affect the ability of the patient to achieve hemostasis. The use of bypassing agents is required for the treatment of bleeding episodes, and the effective use of prophylaxis is greatly diminished in this segment of the population. Much attention has been aimed at improved algorithms to predict inhibitor development and the development of regimens to modify the individual's immune response.19 Patients with inhibitors are fragile and require considerable management expertise. The use of bypassing agents and/or immunotolerance regimens is exceedingly costly. Products with decreased immunogenicity coupled with improved predictive methods would therefore be desirable if they are able to affect inhibitor development.

Therefore, despite major therapeutic advances in the treatment of hemophilia A, opportunities clearly remain to optimize and transform therapy.

Background of long-acting FVIII proteins

A variety of methodologies have been applied to achieve longer-lasting FVIII products. Initial attempts to combine FVIII with pegylated liposomes did not yield a prolonged half-life (T½).20 Specific FVIII modifications to either increase its activity21 or decrease proteolytic degradation22,23 have been attempted, although these specific constructs were not effective in preclinical models and thus did not enter the clinical setting. The greatest success to date has been achieved with either site-specific or controlled covalent attachment to polyethylene glycol (PEG) or the production of fusion proteins with either a monomeric Fc fragment of immunoglobulin G1 or albumin. PEG protects FVIII against proteolytic degradation, whereas fusion technology uses alternative recycling pathways to diminish the impact of natural proteolytic mechanisms for FVIII clearance. These 2 general approaches will be described in greater detail below.

Technology of long-acting FVIII proteins

PEGylation may improve pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics, and immunological profiles and is a well-established technology that has current approved therapeutics in variety of disease states.24 The use of PEG creates a hydrophilic cloud around FVIII and inhibits its proteolytic degradation while allowing its normal function of binding to VWF and participation in coagulation once activated. FVIII clearance is partly attributed to specific binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP1), a hepatic clearance receptor with broad specificity. FVIII T½ can be prolonged in mice when LRP1 is blocked.25 PEG interferes with binding to LRP1 and is likely important in the prolongation of FVIII T½.

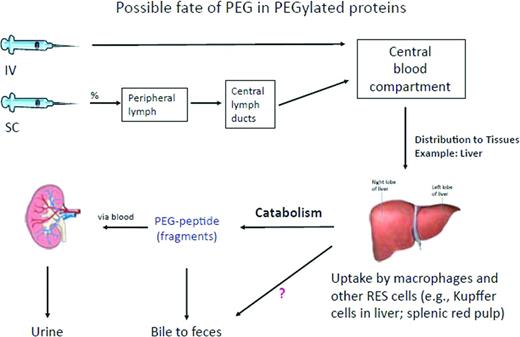

The rate of clearance of PEG FVIII is related to PEG size, with smaller molecules more rapidly cleared.24 Clinical trials with these agents appear to retain desired FVIII properties including binding to VWF while not raising specific clinical concerns. The clearance of PEG, once injected, especially on a regular basis as required for prophylaxis in hemophilia A, has generated discussion and analysis.25 The physiologic site for PEG clearance (eg, renal or liver) is largely dependent on its size (Figure 1). To date, significant PEG-associated adverse events in preclinical studies or clinical trials include a rare occurrence of hypersensitivity reactions. Long-term potential PEG-associated clinical effects, when regularly injected IV, also may relate to the PEG size, PEG number bound to each molecule, and overall yearly calculated PEG load. Ongoing clinical trials with a wider patient base and long-term follow-up are required; however, analyses from currently licensed products using PEG indicate a reasonable safety margin given current yearly PEG exposure estimates.24 There is some evidence that PEG conjugation may affect antigen presentation of FVIII, resulting in deceased antigenicity; the translation of this observation to impact of inhibitor development would be significant but awaits further clinical trials. For a discussion on this topic, please refer to the chapter by Kaufman and Powell in this publication entitled “Molecular Approaches for Improved Clotting Factors for Hemophilia.”26

Removal of PEG in PEGylated proteins administered either IV or subcutaneously. The PEGylated protein is likely removed through the mechanisms specific to the protein, assuming that this takes place in the liver. After degradation of the likely more labile protein part, the PEG molecule remains mostly intact because PEG metabolism is limited. PEG molecules may be excreted mainly by the kidney, but to some extent also through bile.24 Reprinted with permission from Ivens et al.24 Copyright 2012, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Removal of PEG in PEGylated proteins administered either IV or subcutaneously. The PEGylated protein is likely removed through the mechanisms specific to the protein, assuming that this takes place in the liver. After degradation of the likely more labile protein part, the PEG molecule remains mostly intact because PEG metabolism is limited. PEG molecules may be excreted mainly by the kidney, but to some extent also through bile.24 Reprinted with permission from Ivens et al.24 Copyright 2012, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

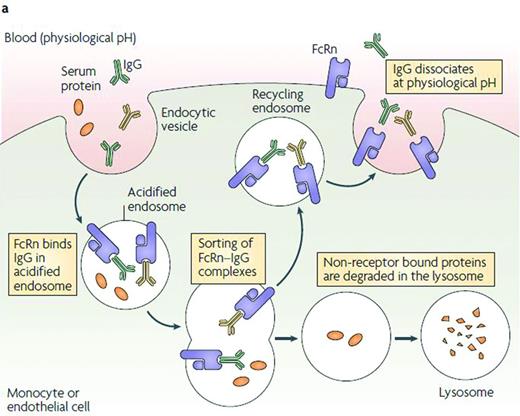

Fusion proteins to either albumin via a linker27 or to a monomeric Fc fragment of immunoglobulin G128 take advantage of natural pathways to prolong FVIII T½; specifically the neonatal Fc-receptor, which results in pH-dependent recycling within endosomes to the plasma membrane, prolonging its T½29 (Figure 2). Although fusion via a linker to albumin for rFIX is under clinical study, the FVIII albumin fusion construct was not pursued.

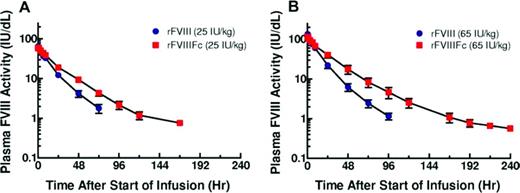

Group mean plasma FVIII activity PK profiles for low- and high-dose cohorts.34 Reprinted with permission from Powell et al.34 Copyright 2012, American Society of Hematology.

Preclinical and clinical studies of long-acting FVIII proteins

Three different rFVIII PEG conjugates are currently in clinical development: B-domain deleted rFVIII (PEG-BDD-rFVIII; BAY 94-9027) has completed phase 1 (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01184820); phase 3 studies are ongoing for PEGylated full-length rFVIII (BAX 855; www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01736475) and glyco-PEGylated rFVIII (N8-GP; www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01480180). These products differ in the length of the FVIII molecule, the cell line in which they are produced, the strategy to combine with PEG, and the size of the PEG used (Table 1).

Long-acting rFVIII clotting factors

*Extrapolated T½ from Advate data.

†Hybrid cell line of HEK293 and a human B-cell line.

N8-GP is a rFVIII with site-directed glycoPEGylation that prolongs T½ while preserving hemostatic activity.35 The rFVIII (N8) is synthesized in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line and has a truncated B-domain of 21 amino acids with demonstrated PK properties similar to those of other current therapies.36 The terminal sialic acid on an O-glycan structure in the truncated B-domain is replaced by a conjugated sialic acid containing a branched 40-kDa PEG that results in a protein with a single PEG attached to the B-domain. Upon thrombin activation, the B dolman is cleaved with the attached PEG, leaving activated FVIII.

The safety and PK of N8-GP was evaluated in patients and compared with their previously used rFVIII product. This dose escalation study (25, 50, or 75 IU/kg/dose) included 26 previously treated patients (PTPs) with severe FVIII. N8-GP was well tolerated at all doses; no patients developed an inhibitor or binding antibodies to rFVIII or N8-GP. The PK of N8-GP was dose linear with a mean terminal T½ of 19 hours (range, 11.6-27.3 hours), representing a 1.6-fold increase over prior products. Clearance was reduced by 30% and the volumes of distributions were similar compared with the patients' comparator products. This product is currently in phase 3 clinical trials.

The most common method to attach PEG is via an attachment to lysine residues or N-terminal amines present in the native protein. Attachment through these mechanisms may lead to inhibition of normal protein function via interference with normal target receptors and binding interactions. Controlled PEG site binding is critical to maintain function and produces a homogeneous, consistent product. Site-specific PEGylation can be accomplished through site-specific mutagenesis that introduces cysteine mutations on the surface of BDD-FVIII. BAY94-9027 was engineered with surface-exposed cysteines to which PEG was conjugated with retention of full in vitro activity and VWF binding. Improved PK was demonstrated in mice and rabbits. PK studies in VWF knock-out mice revealed the larger rFVIII PEG molecule may substitute for VWF to protect the protein from in vivo clearance. The PEGylated rFVIII exhibited prolonged efficacy consistent with improved PK and demonstrated effectiveness in acute bleeding in hemophilic mice.25 A phase 1 study in humans using this agent was recently completed and revealed that it was well tolerated, efficacious, and without serious adverse events. Phase 2/3 studies are ongoing.24 An 8-week prospective, multicenter, open-label nonrandomized phase 1 study in PTPs with severe hemophilia A without inhibitors administered 2 cohorts of 7 patients either 25 IU/kg/dose twice weekly or 60 IU/kg/dose once weekly of BAY 94-9027. The product demonstrated improved PK parameters, with a T½ of ∼ 19 hours compared with the comparator non-Pegylated product, and was well tolerated without immunogenicity.30

BAX 855 is a 20 kDa PEGylated full-length rFVIII. The conjugation process yields 2 moles PEG per FVIII molecule with 60% of PEG chains localized to the B-domain. The PEGylation process is based upon reaction of an activated PEG reagent with accessible amino groups on FVIII and optimized so that mainly the ε-amino groups of lysine residues are targeted and modified. This process does not compromise specific activity and is controlled for production consistency. BAX 855 is reported to retain all physiologic properties of FVIII except binding to the LRP clearance receptor.

Preclinical testing was performed in standard animal models, including FVIII-deficient dogs, knock-out mice, and macaques, and revealed normal activity and prolonged T½ compared with unmodified rFVIII.31

Using Fc fusion technology, rFVIIIFc was developed by fusing a single B-domain–deleted rFVIII, to the dimeric Fc region of IgG1 without intervening linker sequences.28,37,38 rFVIIIFc is produced from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells via recombinant DNA technology. HEK cells ensure fully human, posttranslational modifications,39-42 including glycosylation, with theoretical functional relevance compared with nonhuman mammalian expression systems such as CHO cells, which insert nonhuman glycosylations. Glycosylation modulates yield, bioactivity, solubility, stability against proteolysis, immunogenicity, and clearance rate from circulation.43 Because CHO cells produce glycans at the N-terminal position that differ from human glycans, there is the potential for an increased risk of immunogenicity in humans.43 The biochemical and functional characterization of rFVIIIFc compared with existing FVIII products demonstrated that rFVIIIFc maintains normal interactions with proteins necessary for activity, and with prolonged in vivo activity resulting from fusion with Fc.37 The posttranslational modifications of rFVIIIFc were similar to other rFVIII molecules.37 The binding of rFVIIIFc to VWF was comparable to that of other rFVIII molecules.37 rFVIIIFc specific activity showed that the function of the FVIII moiety of rFVIIIFc was not compromised as a result of the Fc fusion.37

That the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is responsible for the prolonged T½ of rFVIIIFc was also confirmed; the T½ of rFVIIIFc was approximately 2-fold higher than that of rFVIII in hemophilia A mice, hemophilia A dogs, normal mice, and transgenic mice expressing human FcRn. In contrast, the T½ of rFVIIIFc was comparable to rFVIII in FcRn knock-out mice, confirming that the interaction between FcRn and the Fc fragment is responsible for conferring protection of the Fc fusion protein from degradation.38

PK of rFVIIIFc

In the first-in-human phase 1/2a study (wwwClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01027377), 16 PTPs with severe hemophilia A (< 1% FVIII activity) received a single dose of either 25 or 65 IU/kg rFVIII followed by an equal dose of rFVIIIFc.34 rFVIIIFc showed an ∼ 1.5- to 1.7-fold increase in mean T½ (18.8 hours for both 25 and 65 IU/kg rFVIIIFc vs 12.2 hours for 25 IU/kg rFVIII and 11.0 hours for 65 IU/kg rFVIII; P < .001 for both comparisons).34 rFVIIIFc showed a 30% to 35% reduction in clearance compared with rFVIII. rFVIII and rFVIIIFc had comparable dose-dependent peak plasma concentrations and recoveries (Figure 3).

FcRn recycling pathway.29 IgG and Fc fusion proteins are taken up from circulation into cells by nonspecific pinocytosis and/or endocytosis mechanisms.49 As the endosomes become acidic, the Fc domain of IgG or Fc fusion proteins binds to FcRn. Once the endosome fuses back at the cell surface, Fc dissociates from FcRn at neutral pH and IgG and Fc fusion proteins are released back into the circulation.49 In contrast, circulating proteins that do not interact with FcRn are trafficked to endosomal and lysosomal degradation pathways.29,50 Ultimately, Fc degrades naturally and does not accumulate in the body.51 Despite its name, the expression of human FcRn is stable throughout life.52 Reprinted with permission from Roopenian and Akilesh.29 Copyright 2007, Nature Publishing Group.

FcRn recycling pathway.29 IgG and Fc fusion proteins are taken up from circulation into cells by nonspecific pinocytosis and/or endocytosis mechanisms.49 As the endosomes become acidic, the Fc domain of IgG or Fc fusion proteins binds to FcRn. Once the endosome fuses back at the cell surface, Fc dissociates from FcRn at neutral pH and IgG and Fc fusion proteins are released back into the circulation.49 In contrast, circulating proteins that do not interact with FcRn are trafficked to endosomal and lysosomal degradation pathways.29,50 Ultimately, Fc degrades naturally and does not accumulate in the body.51 Despite its name, the expression of human FcRn is stable throughout life.52 Reprinted with permission from Roopenian and Akilesh.29 Copyright 2007, Nature Publishing Group.

Interestingly, individual VWF levels correlated well with both rFVIIIFc clearance (R2 = 0.5492, P = .0016) and T½ (R2 = 0.6403, P = .0003). An important observation is that Fc fusion technology does not prolong the T½ of rFVIIIFc and rFIXFc to the same extent, one potential explanation being the association of rFVIIIFc with VWF. Unlike FIX, ∼ 98% of FVIII circulates in complex with VWF.44 The approximate 18-hour T½ of VWF45 is thought to limit the degree to which the T½ of rFVIII products can be extended,25,34,38 which is consistent with the observed T½ of rFVIIIFc in the phase 1/2a study and the reported T½ with PEG-modified FVIII products in trial (Table 1).

Clinical safety of rFVIIIFc

In the phase 1/2a study in 16 PTPs, rFVIIIFc was well tolerated at both 25 and 65 IU/kg.34 No drug-related serious adverse events were observed. No serious bleeding episodes were observed and, importantly, no inhibitors, non-neutralizing antibodies, or allergic reactions were reported.

Clinical development of rFVIIIFc

Pivotal phase 3 study

A-LONG, an open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study designed to evaluate the safety, PK, and efficacy of rFVIIIFc in PTPs with severe hemophilia A (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01181128), was recently completed. A-LONG enrolled patients ≥ 12 years of age into 3 study arms: (1) individualized prophylaxis (3- to 5-day intervals), (2) weekly prophylaxis, and (3) episodic (on-demand) treatment. Patients from each treatment arm were eligible to enter a surgery subgroup. The primary safety end point was the development of inhibitors and the primary efficacy end point for A-LONG was the annualized bleeding rate. PK of rFVIIIFc versus rFVIII (Advate), number of injections required for bleed control, and perioperative hemostasis were evaluated.

The dosing regimens investigated in A-LONG, once published, will provide valuable information on the impact that rFVIIIFc may have on current hemophilia care. Although the individualized prophylaxis arm enabled patients to extend their dosing interval, data from the weekly prophylaxis arm will provide insight into how this fixed regimen may potentially provide a more appealing option for individuals who currently receive episodic treatment. A weekly regimen could lead to a change in attitude in such individuals and guide them toward individualized prophylaxis and its associated benefits.

Ongoing rFVIIIFc studies

Because many hemophilia patients are children, further study in the pediatric population is important. The Kids A-LONG study (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01458106) is currently recruiting ∼ 50 children < 12 years of age who have severe hemophilia A and have had at least 50 documented prior exposures to FVIII. The study is designed to evaluate the prophylactic use of rFVIIIFc for the control and prevention of bleeding in previously treated children. The frequency of inhibitor development is the primary outcome measure and annualized bleeding rate and response to treatment for bleeding episodes are secondary outcome measures. PK parameters are particularly important to assess in the pediatric population because they may differ relative to patient age or body weight. Indeed, rFVIII clearance has been shown to decline and T½ to increase with age46 and it has been suggested, based on PK studies, that the dose required to maintain a desired trough level during prophylaxis may therefore require adjustment every 2 years or when significant weight gain occurs.47

Patients who complete the A-LONG and Kids A-LONG studies have the option to continue treatment in the extension study, ASPIRE (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01454739). ASPIRE is evaluating the long-term safety and efficacy of rFVIIIFc and has 2 treatment regimen options: prophylaxis and episodic treatment.

Conclusions

Many practical hurdles are associated with current therapeutic regimens for treating hemophilia. The relatively short T½ of available coagulation factor products necessitate frequent infusions, with recurrent venipuncture often leading to CVAD use in young children, which in turn is associated with a risk for thrombosis, infection, and mechanical failures. Current regimens aim to maintain trough levels at or above 1% between doses. Nonetheless, optimal treatment regimens for hemophilia have yet to be defined; some patients bleed despite having a trough level above 1%, whereas others having undetectable trough levels do not experience breakthrough bleeding. Peak levels have been demonstrated to be important in the development of breakthrough bleeding and require further evaluation.48

The advent of long-acting products represents an important advance in the management of hemophilia, with the potential to change current care paradigms. Long-lasting products could provide the opportunity for prolonged protection from bleeding and bleed resolution with fewer injections. Institution of early prophylaxis with once weekly infusion through peripheral venipuncture may be feasible in very young children. The need for CVADs and their associated risks could decrease. Less burdensome regimens using long-acting products offer the potential for enhanced protection with increased adherence and, therefore, improved long-term outcomes. Patients on episodic treatment may be encouraged to transition to a prophylaxis regimen to improve joint outcomes and ultimately quality of life. Long-acting coagulation factors provide an opportunity to target higher trough levels and improved individualized treatment, resulting in increased protection from bleeding episodes. It is currently accepted that higher trough levels may be needed for some patients or in specific circumstances (eg, for participation in sports and activities). However, our current paradigm for target trough levels in prophylaxis regimens approximating 1% may be reconsidered and challenged with the advent of longer-lasting replacement therapies. Ease of measurement of these newer agents with currently available standardized assays will allow our current treatment protocols to change over time without significant difficulty. Long-acting factors have the potential to substantially improve acute management of bleeds, markedly simplify prophylactic regimens, and provide an opportunity for improved individualized treatment for hemophilia A. How these products will affect the current cost of therapy is as yet unknown.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Natalie Duncan for her excellent assistance.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Amy D. Shapiro, MD, Medical Director, Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, 8402 Harcourt Rd, Suite 500, Indianapolis, IN 46260; Phone: 317-871-0000; Fax: 317-871-0010; e-mail: ashapiro@ihtc.org.