Abstract

Mrs G is a 54-year-old woman with a diagnosis of chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia dating back 8 years. She had a low-risk Sokal score at diagnosis and was started on imatinib mesylate at 400 mg orally daily within one month of her diagnosis. Her 3-month evaluation revealed a molecular response measured by quantitative RT-PCR of 1.2% by the International Scale. Within 6 months of therapy, she achieved a complete cytogenetic response, and by 18 months, her BCR-ABL1 transcript levels were undetectable using a quantitative RT-PCR assay with a sensitivity of ≥ 4.5 logs. She has maintained this deep level of response for the past 6.5 years. Despite her excellent response to therapy, she continues to complain of fatigue, intermittent nausea, and weight gain. She is asking to discontinue imatinib mesylate and is not interested in second-line therapy. Is this a safe and reasonable option for this patient?

Introduction

Since the approval of imatinib mesylate (IM), the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) has changed dramatically.1 Durable cytogenetic and molecular responses are observed with IM therapy, and dasatinib and nilotinib have demonstrated earlier and deeper responses compared with IM when used in the frontline setting.2-5 One of the most frequently asked questions for patients with durable complete molecular responses (CMRs) is whether they can safely discontinue treatment without relapse of their disease. Before reviewing this issue, it should be noted that various definitions of CMR have been used in clinical trials. Recently, more precise definitions of International Scale deep molecular responses (MRs) are being used in place of the term “CMR.” These definitions include MR4 (BCR-ABL1 ≤ 0.01%), MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%), and MR5 (BCR-ABL1 ≤ 0.001%).6,7 A negative assay should have an assay sensitivity of at least 4.5 or 5 logs as interpreted by the copies of control gene present. With the high cost of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy and the diminished quality of life noted over time in a significant proportion of patients with CML, the idea of a holiday from therapy or eliminating the need for lifelong therapy is appealing to many.8-11 The question then becomes, is it safe?

Methods

To address this question, we searched for data regarding discontinuation of TKIs in CML patients by performing a PubMed search using the MeSH terms “Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive” AND “imatinib” OR “dasatinib” OR “nilotinib,” which was followed by a second search using the above phrase AND “discontinuation.” When applying limits of studies published in the last 10 years in the English language, this resulted in 80 references and these were then limited to only clinical trials,12-16 case series, and case reports.17-22 Lastly, all abstracts submitted to the 2011 and 2012 ASH annual meeting with the term “CML” were reviewed and resulted in one abstract from 2011 and 2 from 2012 describing relevant clinical trials or case series/reports.23-26 Three seemingly relevant ASH abstracts were eliminated because either an updated abstract was available27,28 or a more in-depth manuscript had been published with the data from the abstract.29 One abstract from the 2012 (no. 0189) and one from the 2013 (no. 4401) European Hematology Association meetings were also found.30,31 All additional publications and abstracts addressing the topic of TKI discontinuation in CML directly were reviewed.32-38

Results

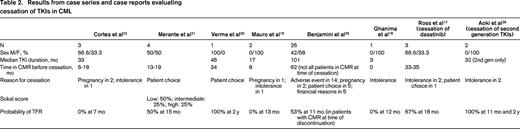

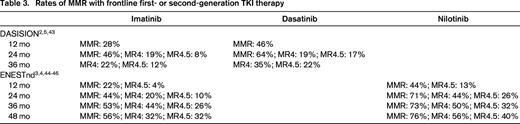

Seven prospective trials and 2 retrospective trials analyzing TKI discontinuation in CML are summarized in Table 1. Because definitions of CMR, molecular relapse, and thresholds to resume TKI treatment varied, these variables are also summarized. The eligibility criteria for patients to enroll on the prospective discontinuation trials were strict, with a persistent CMR for a minimum of 2 years being required in 6 of these studies. It should be noted that the probability of treatment-free remission (TFR) appears higher in trials that did not intervene before loss of MMR occurred.23,24,30 One trial evaluated patients after cessation of second-generation TKIs and demonstrated similar outcomes. Six case series and 2 case reports are described in Table 2. The case series report higher rates of relapse after discontinuation compared with the prospective studies. Many of these studies included a subset of patients treated with IFN-α before beginning IM. We also chose to include 2 studies reporting very low rates of molecular relapse.23,24 These studies used a higher threshold of molecular relapse before reinitiating therapy (loss of MMR), and one-third to one-half of these patients received prior autologous transplantation. Nonetheless, the results of these trials and studies are consistent, and demonstrate that in a select group of patients, ∼ 40% to 50% may remain off therapy for an extended period.

Results from prospective and retrospective trials evaluating cessation of TKIs in CML

IS indicates International Score; and Q-PCR, quantitative PCR.

*Previous stem cell transplantation was allowed in some patients.

†Assay sensitivity was not reported.

‡Second-generation TKIs, dasatinib and nilotinib after IM intolerance or suboptimal response to IM.

§This trial included 23 patients who had previously undergone an allogeneic stem cell transplant, 3 patients received second-generation TKIs for IM intolerance.

‖Some of these patients were included in the analysis of the Korean KIDS study as well.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that discontinuation of first- and second-generation TKIs may lead to a prolonged treatment-free period in nearly half of all patients despite differences in the definition of CMR, molecular relapse, and indications to restart therapy (Table 1).14-16,23,24,30,32,34,37-39 Comparing patients in Table 1 (clinical trials) and Table 2 (case series), it is apparent that durable stable CMR before discontinuation is important to limit molecular relapse. Multivariate analyses have identified factors associated with molecular relapse and with prolonged TFR. High risk Sokal score is a significant independent risk factor for relapse after cessation of TKIs. Factors associated with longer TFR include prior IFN therapy before TKI therapy, longer duration of CMR before discontinuation, and longer duration of IM use before discontinuation (> 60 months).12,13,15,39,40 In addition, achievement of an early deep molecular response at 3 months is associated with durable deep molecular response.40-42

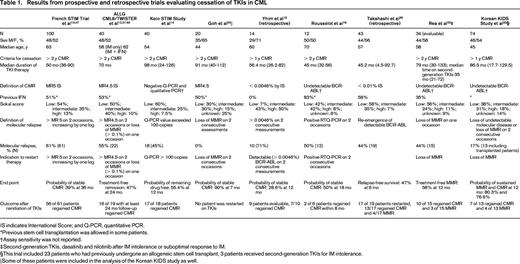

It is unknown at this time if second-generation TKIs result in an increased probability of TFR. However, the 2 case series in Table 2 and the study by Rea et al in Table 1 report results that appear superior to IM-treated patients.17,26 Table 3, where the percentages of patients who achieved specific molecular responses on IM, nilotinib, and dasatinib on either the ENESTnd or DASISION trial are listed, highlights the increasing relevance of the question of whether TKI therapy can be stopped.2-5,43-46 With 48 months of follow-up, ∼ 40% of patients on second-generation TKIs achieve MR4.5.44 As may be expected, achievement of MR4.5 occurs later with IM therapy, but 23% of patients treated with IM on ENESTnd achieved these deep molecular responses at 4 years and the numbers of patients achieving these responses will likely continue to increase over time.44 In many cases, these responses appear to be durable.

Our review suggests that for patients with durable deep molecular responses, stopping TKI therapy is reasonably safe. At this time, based on current predictions of deep molecular responses on first-and second-generation TKIs, ∼ 10% to 20% of patients may maintain a long-term remission off therapy.2,4,12 As outlined in Table 1, 50% to 60% of patients who stopped TKI therapy experienced molecular relapse and most were restarted on the same or an alternative TKI. Currently, none of these patients has progressed to advanced-phase CML and many (although not all) patients who reinitiated therapy regained their previous molecular response.12,13,15,35,39,47 Notably, when molecular relapse occurred, in most cases it occurred within the first 6 months off therapy.12,23,33 To date, it is unclear why TKI therapy can be stopped if hematopoietic stem cells are inherently resistant to TKIs. Supporting the idea of quiescent residual CML stem cells, DNA-PCR for BCR-ABL was performed for 26 patients in the CML8 study at the time of treatment discontinuation. Thirteen of these patients have maintained long TFRs despite having a positive DNA-PCR result.12,36 Nonetheless, some caution may be warranted because it remains possible that off therapy years later, a leukemic stem cell with genetic features of more advanced and resistant CML could emerge in some patients. This possibility is supported by the fact that very late lapses do occur rarely after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.48

Therefore, in summary, although Mrs G. did not have a deep molecular response at 3 months, her subsequent course suggests that she has an ∼ 50% chance of a prolonged TFR off IM. Nevertheless, given the uncertainties discussed above, we recommend continuing TKIs over discontinuing them outside the context of a clinical trial (grade 2C).

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Kendra Sweet, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, 12902 Magnolia Dr, Tampa, FL 33612; Phone: 813-745-4294; Fax: 813-745-3875; e-mail: Kendra.Sweet@Moffitt.org.