Abstract

Reduction of atrial fibrillation–associated stroke risk has become the leading indication for warfarin use. Optimal management of warfarin can only be achieved with a relatively complex infrastructure. Alternative anticoagulant agents have been developed, and 3 have demonstrated effectiveness, safety, and adherence that are comparable or superior to warfarin in the clinical trial setting. None of the novel agents requires routine laboratory testing to demonstrate effective anticoagulation. Whereas these new agents present potential advantages, such as fixed dosing and dramatically reduced intracranial hemorrhaging, they are also subject to caveats that ought to be considered in the context of an “ideal” anticoagulant. If used casually, they have the potential to worsen rather than improve health care outcomes. There is little question that the management burden of the novel agents will be less than with warfarin. However, with a hemorrhagic risk that was similar to warfarin in these trials, there will likely remain a significant need for both baseline education and some level of focused interval follow-up to assess for bleeding risk and adherence considerations. These novel agents offer a definite advance in the available management options for thromboembolic disease, but until we understand the requirements for safe and effective use in the routine clinical setting, we will not be able to establish the extent to which they should replace warfarin.

Background

Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin have been the mainstay of oral anticoagulant therapy since the 1940s. The effectiveness of warfarin in the reduction of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF)–associated stroke in the late 1980s led to a dramatic increase in the use of warfarin. It has been projected that between 2010 and 2040, the number of adults with atrial fibrillation (AF) in the United States will double.1 In 2009, more than 2 million US patients were initiated on warfarin therapy for all of its indications, resulting in more than 30 million prescriptions per year.2–3

The underlying challenge in treating thromboembolic disease states is the inherent tension between hemostasis and thrombosis. The benefits of reduced thromboembolism come at a cost of increased bleeding. This challenge is compounded with warfarin due to the difficulty in achieving and maintaining the desired level of anticoagulant intensity in individual patients due to a wide intra- and interpatient variations in dose requirement.

Warfarin management has evolved dramatically. Laboratory testing has become more standardized with the adoption of the international normalized ratio (INR) and improvements in thromboplastin reagents. Flexibility in testing has been obtained with the development of point-of-care INR testing devices and the potential for patient self-testing and self-management. Systematic approaches to management, such as anticoagulation clinics and computerized management and tracking systems, have been well documented to improve clinical outcomes. In addition, the outcomes with warfarin in the clinical trial setting have continued to improve.4 However, the reality is that many patients do not have access to specialized anticoagulation clinics and therefore warfarin therapy remains underused and frequently suboptimally managed.5

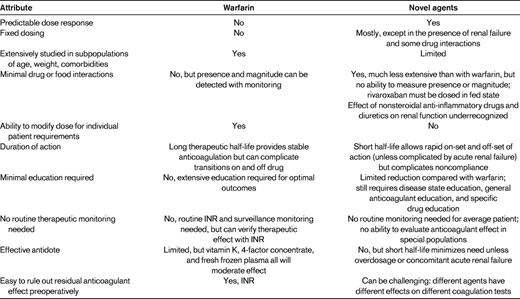

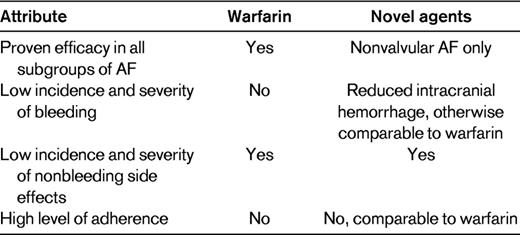

The well-known challenges of warfarin therapy have given rise to multiple proposals as to what the characteristics of the ideal anticoagulant should be.6–8 When attempting to determine the extent to which the novel agents should replace warfarin, there are 3 primary characteristics to be considered. The first is efficacy. The purpose of anticoagulant therapy in NVAF is the reduction of stroke risk. Unless the novel agents are at least as effective as warfarin, there will be less incentive to use them. Safety is the second major consideration, specifically, whether the level of efficacy is worth the cost in bleeding and if other safety concerns may arise. Long-term adherence is the third primary characteristic. Even if a novel therapy is highly effective and relatively safe, if patients are unable or unwilling to continue to take the drug for an extended time, its ability to reduce the stroke burden will be compromised. These primary characteristics of an ideal anticoagulant for reduction of stroke in AF are summarized in Table 1 and are discussed separately in the sections below. Other characteristics of an ideal agent that contribute to or are considered secondary to these 3 primary characteristics are summarized in Table 2. In this review, the development of alternatives to chronic warfarin therapy and how well these alternatives compare with warfarin relative to the characteristics of an ideal anticoagulant and in the transition from a clinical trial to a clinical practice setting are discussed.

Primary characteristics of an ideal anticoagulant for reducing stroke risk in atrial fibrillation

Development of warfarin alternatives

The original attempts to find alternatives to warfarin focused on antiplatelet agents, including combination therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel as in the Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W) trial.9 However, warfarin was consistently shown to be far superior to both aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for stroke prevention in AF.

Ximelagatran (trade name Exanta; Astra Zeneca) was the first of the new generation of oral direct thrombin inhibitors. Ximelagatran was administered in fixed doses without routine coagulation monitoring. In the Stroke Prevention with the Oral Direct Thrombin Inhibitor Ximelagatran Compared with Warfarin in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation (SPORTIF) series of trials, ximelagatran was evaluated against dose-adjusted warfarin and demonstrated comparable safety and efficacy when used for AF-associated stroke reduction.10,11 The potential for liver toxicity prevented its clinical approval.12

Once the potential for fixed-dose unmonitored therapy was demonstrated, the development of additional agents intensified. Dabigatran (trade name Pradaxa; Boehringer Ingelheim), another oral antithrombin, was evaluated in the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial.13 This was a noninferiority trial of dose-adjusted warfarin versus fixed doses of either 110 mg or 150 mg twice daily of dabigatran. The primary efficacy end point was stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic) or systemic embolism. Warfarin in RE-LY was well managed, with a 64% time in the therapeutic range. Dabigatran 150 mg demonstrated superiority in efficacy, with a 35% reduction in stroke compared with warfarin and significant reductions in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Despite the remarkable improvement in efficacy with dabigatran 150 mg, the overall risk of major bleeding remained similar to warfarin, life-threatening bleeding was reduced, and there was a dramatic reduction in intracranial bleeding; however, gastrointestinal tract bleeding was increased with the 150 mg dose. Dabigatran 110 mg demonstrated noninferiority to warfarin for stroke reduction, but demonstrated significantly less risk of major or life-threatening bleeding and a remarkable 69% reduction in the risk of intracranial bleeding. The 150 mg dose was approved in the United States for the reduction of AF-associated stroke in the fall of 2010.

Rivaroxaban (trade name Xarelto; Bayer) is another alternative anticoagulant that inhibits factor Xa directly rather than targeting thrombin. Rivaroxaban was compared with warfarin in the Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET-AF) trial and demonstrated noninferiority with a fixed dose of 20 mg once a day (15 mg once a day in impaired renal function) and no requirement for routine anticoagulation monitoring.14 As with dabigatran, the major bleeding rates were comparable to warfarin, but there was again a significant reduction in intracranial bleeding. Rivaroxaban was approved in early 2012 for the reduction of AF-associated stroke.

A third agent, apixaban (trade name Eliquis; jointly marketed by Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb), another direct-acting anti–factor Xa agent, was evaluated with a fixed dose of 5 mg twice a day (2.5 mg twice a day in impaired renal function) versus dose-adjusted warfarin in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial and demonstrated reductions in stroke, major bleeding, and mortality.15 In the Apixaban Versus Acetylsalicylic Acid to Prevent Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Who Have Failed or Are Unsuitable for Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment (AVERROES) trial, apixaban was also evaluated against aspirin in warfarin-ineligible patients with AF and demonstrated superiority in stroke reduction.16 Apixaban is currently under review with the US Food and Drug Administration.

Warfarin versus novel agents: insights from clinical trials

Efficacy

All 3 novel agents have demonstrated comparable or improved efficacy relative to warfarin when used in fixed doses without routine coagulation monitoring. All of the new agents do require a dose reduction when used in the presence of significant renal impairment. However, the magnitude of incremental improvement relative to warfarin is relatively modest compared with the magnitude of improvement that warfarin provides relative to placebo.

Safety

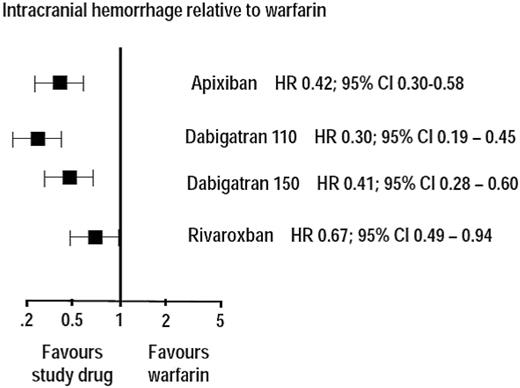

One of the biggest concerns with warfarin has been the frequency and severity of bleeding complications, and it had been hoped that an “ideal” anticoagulant would have a low incidence of bleeding complications. However, with the novel agents, even though intracranial bleeding is dramatically reduced (Figure 1), only dabigatran and apixaban have demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in major bleeding. Although by no means insignificant, the ability of the novel agents to reduce bleeding complications relative to warfarin is relatively limited compared with the increase in bleeding caused by all current anticoagulants. Fortunately, neither warfarin nor the novel agents appear to have a major incidence of severe nonhemorrhagic side effects.

Relative risk reduction in intracranial hemorrhage with novel anticoagulants relative to warfarin.

Relative risk reduction in intracranial hemorrhage with novel anticoagulants relative to warfarin.

Adherence

The third primary characteristic is adherence to therapy for a prolonged period of time. The terminology related to this issue is evolving, but adherence relates both to the ability to take a medication as prescribed (eg, twice a day) on a regular basis and the ability to stay on that regimen for the desired period of time.17 Nonadherence, particularly in clinical trials, is multifactorial and relates to the tolerability of the drug itself, adverse events, complexity of the treatment regimen or study protocol, and level of symptom relief provided by the treatment.18 The impact of nonadherence on cardiovascular outcomes in particular and the need for approaches to improve adherence are receiving increased recognition.19,20

It has been well recognized that long-term adherence to warfarin can be a challenge and that a significant proportion of patients stop therapy within the first couple of years. However, even in the setting of clinical trials, long-term adherence to the novel agents also appeared to be a challenge. In the 2.5 years of the RE-LY trial, there were more patients who discontinued dabigatran (21%) than warfarin (16%), but the excess discontinuance was limited to the first 3 months of exposure and may be related to dyspepsia. In the ROCKET-AF trial, more than 20% of the patients in each arm discontinued therapy. In the ARISTOTLE trial, more than 25% of patients in each arm discontinued therapy.

Several additional characteristics differentiate the new agents from warfarin. These agents have a much more rapid onset and offset of action, there are no significant food-drug interactions, and drug-drug interactions are dramatically reduced relative to warfarin, resulting in a potentially more favorable benefit-risk profile overall.

Disconnect between clinical trials and clinical practice

We always learn more about new agents as they are used more widely, so we must remain cautious and observant as we gain more experience with any new agents. This is particularly true with anticoagulants, in which the potential to cause significant harm is greater than with many other classes of drugs. Clinical practice is very different from the clinical trial setting, with several significant caveats that may make it difficult to realize the potential advantages of these agents. Several of these considerations are general and are relevant to all of the new agents and to all patients, whereas others are individual patient considerations.

General considerations

Can similar efficacy be achieved without similar education?

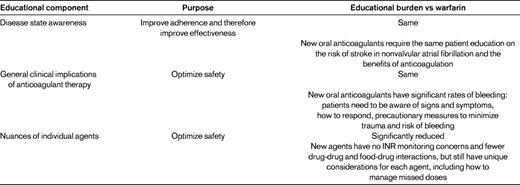

The results obtained in the clinical trials were obtained within a defined infrastructure that provided significant baseline education. To be enrolled in any of these studies, the patients received education relating to baseline disease state, education on the general clinical implications of anticoagulant therapy, and education on the nuances of the specific anticoagulant being studied. These educational components, their purpose, and the related educational burden for these new agents relative to warfarin are summarized in Table 3. In the randomized trials, all of the patients received the same amount of education. But how much education will be provided to patients prescribed these agents in clinical practice if they are not followed in an anticoagulation clinic?

Educational components for patients receiving anticoagulation for AF stroke risk reduction and the educational burden for novel anticoagulants relative to warfarin

Garcia et al published a consensus statement relating to the optimization of warfarin therapy and included content topics for education.21 Eighteen important aspects of anticoagulation education were delineated and, at most, only 5 of these were specifically related to warfarin. The other 13 were relevant to any patient receiving chronic oral anticoagulant therapy.

We have no data from the trials to provide insight as to the minimum education content that should be provided to patients receiving novel anticoagulants. However, there are significant data derived from actual clinical settings that identify how much time physicians spend in discussing prescribed medications with patients.22 In most primary care settings, the average time for a patient visit is between 15 and 20 minutes. The actual amount of communication time between physician and patient is an average of 3.5 minutes. In an evaluation of primary care and specialty providers and cardiologists, when new medications were prescribed, a mean of 49 seconds was allocated to discussion of the new medication, including purpose, directions, and side effects!23 A similar study found that physicians fulfilled a mean of 3.1 of 5 expected elements of communication when initiating new prescriptions.24

Particularly in an arena of preventive medicine, such as AF-associated stroke reduction, patients do not feel better nor do they experience relief from symptoms just because they are taking an anticoagulant. There is minimal incentive to take their medications unless there is a full understanding of the underlying disease state and the benefit and risk implications of the therapy. The component of education most relevant to maintaining efficacy is that related to disease-state awareness: educating patients to understand the relationship between AF and stroke and the relationship between effective anticoagulation and stroke risk reduction and the expected duration of anticoagulation. Disease-state awareness education is independent of the anticoagulation agent to be considered, so the burden of this educational component will be similar for the new agents to what has been done for warfarin. If adequate disease-state awareness education is not available to a patient, there is reason to be concerned that compliance, and therefore efficacy, will be compromised. As stated by Dr C. Everett Koop, former US Surgeon General, “Drugs don't work in patients who don't take them.”25

Can similar safety be achieved without similar education and follow-up?

The education provided in the clinical trials not only had the potential to contribute to effectiveness, it also provided the opportunity to enhance safety through an awareness of the signs and symptoms of bleeding and what to do if they occur, precautionary measures to minimize the risk of trauma or bleeding, and the importance of notifying other health care providers that they are taking an anticoagulant.

A further contribution to safety was provided by the anticoagulant-focused and structured follow-up regimen that was present in the clinical trials. All of the patients in the trials received ongoing anticoagulant-focused interval follow-up that provided the opportunity for reinforcement of anticoagulation education (such as the warning signs of bleeding) and compliance education and reinforcement and surveillance for interacting medications.

An evaluation of adverse drug events requiring emergency hospitalizations in older adults demonstrated that warfarin was responsible for more than one-third of the admissions (more than any other medication) and for more than twice the frequency of admissions related to insulin therapy, making it the second highest contributor to hospital admissions from adverse drug effects. The novel anticoagulants all retain significant potential to cause major bleeding, so the need for education on general anticoagulation considerations will remain similar to warfarin. However, the need for agent-specific education will be significantly reduced relative to warfarin because there will not be any need for education on dietary modifications or INR monitoring issues and the education related to drug-drug interactions will also be reduced. If adequate education on general anticoagulation considerations is not available to a patient and no anticoagulation-focused follow-up is available, there is the potential for hemorrhagic complications to exceed what was seen in the trials.

Can adherence be achieved without education and follow-up?

Discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy was a challenge in all of the trials and remained comparable between warfarin and the novel agents despite the education and systematic follow-up provided in the trial setting. There is reason to be concerned that in the clinical practice setting, in the absence of any significant education and in the absence of any follow-up focused on anticoagulant considerations, nonadherence will be a much more significant concern than it was in the trials. Nonadherence has been demonstrated to be a significant challenge in the Medicare population, in which 27% of patients who skipped doses or stopped medications failed to report this to their physicians. Remarkably, 39% of patients who discontinued medications because of excessive costs also failed to share this information with their health providers. An early assessment of dabigatran use by a large pharmacy provider highlights these concerns, showing a 17% nonadherence rate by the end of the first 4 months of treatment.26

How to manage drug-drug interactions.

There is no question that the potential for drug-drug interactions is significantly reduced with all of the new agents. However, such interactions have not been eliminated. Whereas it is true that warfarin has an extremely large and unpredictable list of drug-drug interactions, the management is fairly straightforward: measure the INR and adjust the dose as needed. Unfortunately, with the novel agents, there is no current testing or monitoring modality that is able to detect either the presence or the magnitude of a drug interaction. It is disingenuous to believe that the majority of prescribing physicians will actually memorize a list of the potential interacting agents. It is true that there are relatively few agents that are absolutely contraindicated, but for those that are known to be used with caution, it is very difficult to know how to interpret the implications of their use. Are 2 weak inhibitors the equivalent of a strong inhibitor or does it take 3? In addition, many physicians might not readily realize that any agent that affects renal function can cause problems with any of the new agents. For example, diuretics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents are capable in some elderly patients of causing clinically significant changes in renal function.

Understanding nuances of individual drugs.

Each of the new agents has individual nuances that need to be communicated to the patient and understood by their health-care provider. Examples include the humidity sensitivity of dabigatran capsules and the potential for dyspepsia with this drug. All 3 of the new agents have unique drug-drug interaction profiles.

Novel agents are rarely fully understood.

All of these new agents were evaluated in very large trials with thousands of enrolled subjects. However, we have seen multiple examples of new therapeutic agents that have done well in trials, been approved for clinical use, and then, based on real-world experience, have either been withdrawn from the market (eg, rofecoxib, trade name Vioxx, Merck, and troglitazone, trade name Rezulin, Daiichi-Sankyo) or significantly restricted (eg, rosiglitazone, trade name Avandia; GlaxoSmithKline). It is realistic to assume that there will be many prescribers who will want to wait to see what the clinical experience reveals before initiating use.

Patient-specific considerations

Compliance and adherence.

If a patient is already on warfarin and has erratic control of anticoagulation due to variable compliance, there is a significant chance that they will be just as noncompliant with a novel agent. The novel agents have a much more rapid offset of action than warfarin, so brief episodic noncompliance may be more significant than with the occasional missed dose of warfarin. There are some patients for whom the routine warfarin-monitoring visits are as much for compliance enhancement as for actual INR value testing.

Comorbidities.

Patients with significant or fluctuating renal dysfunction may be better off with warfarin. This may include patients with significant heart failure, who may be at increased risk of renal dysfunction due to fluctuating control of their heart failure, and variations in diuretic dosing. Patients with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding may not be good candidates for dabigatran or rivaroxaban. None of the novel agents are yet approved for the treatment of patients with mechanical heart valves, and treatment of acute venous thromboembolic disease is evolving but is not yet approved in the United States. Therefore, for the foreseeable future, patients with other thromboembolic conditions in addition to AF will continue to be best managed with warfarin.

Cost.

Most of the companies offer some degree of financial hardship assistance, but for a significant number of patients, the out-of-pocket costs may simply be prohibitive.27

Summary and conclusions

The novel anticoagulants provide a significant advance in our ability to prevent and treat thromboembolic conditions such as stroke risk reduction in NVAF. They provide additional options to optimize anticoagulant therapy for individual patients. Patient education requirements will be less stringent than with warfarin, but will still be needed in the 3 areas of disease-state awareness, general clinical implications of anticoagulant therapy, and the nuances of the particular anticoagulant prescribed. Anticoagulant-focused interval follow-up will be less burdensome than with warfarin, but will still be needed. If these drugs are used in a casual “prescribe and forget” manner, the resulting clinical outcomes will be less favorable than what was seen in the clinical trials and may well be significantly worse compared with reasonably well-managed warfarin. Until more is known of the education requirements and the intensity of surveillance and monitoring to optimally use these new anticoagulants in real-world clinical settings, warfarin will continue to have a significant role in the anticoagulation armamentarium.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from Sanofi, Mobius, and Roche Diagnostics; has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Roche Diagnostics, and Alere Medical; has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche Diagnostics, St Jude Medical, and Alere Medical; and has been affiliated with the speakers' bureaus for Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche Diagnostics, and St Jude Medical. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Alan Jacobson, MD, Director, Anticoagulation Services, VA Loma Linda Healthcare System, 11201 Benton St, Loma Linda, CA 92357; Phone: 909-825-7084; e-mail: alan.jacobson@va.gov.