Abstract

Economic evaluation in health care is increasingly used to assist policy makers in their difficult task of allocating limited resources. The high cost of care, including that for clotting factor concentrates, makes hemophilia a potential target for cost-cutting efforts by health care payers. Although the appropriate management of hemophilia is key to minimizing and preventing long-term morbidity, comparative effectiveness studies regarding the relative benefit of different treatment options are lacking. Cost-of-illness (COI) analysis, which includes direct and indirect costs from a societal perspective, can provide information to be used in cost-effectiveness and other economic analyses. Quality-of-life assessment provides another methodology with which to measure outcomes and benefits of appropriate disease management. Health care reform has implications for individuals with hemophilia and their families through changes in payment, insurance coverage expansion, and health care delivery system changes that reward quality and stimulate cooperative, team-based care. Providers will benefit from the expansion of insurance coverage and some financial benefits in rural areas, and from the expansion of coverage for preventive services. Accountable care organizations will potentially change the way providers are paid and financial incentives under reform will reward high quality of care.

Introduction

Economic evaluation in health care is increasingly used to assist policy makers in their difficult task of allocating limited resources. Although hemophilia is a rare condition affecting a small portion of the population, the costs are disproportionately high and therefore are of increasing economic interest to payers of health care. The high cost of clotting factor concentrates and the even higher cost of treatment of inhibitors makes hemophilia a potential target for cost-cutting efforts by health care payers. Also contributing to this economic interest is that hemophilia is a condition that can be associated with significant morbidity and lifelong treatment. That is, repeated hemorrhaging into joints, particularly in patients with severe hemophilia, can lead to the development of chronic joint disease.1 These individuals may suffer from joint pain, loss of range of motion, and crippling musculoskeletal deformity and disability, all of which impair their quality of life and have implications for employment, productivity, and other psychosocial aspects.2–4

The appropriate management of hemophilia is key to minimizing and preventing long-term issues that can contribute to higher costs. However, long-term comparative effectiveness data regarding the relative benefit of different treatment options to guide therapeutic decision making are lacking. Until recently, there were no studies that assessed the entire cost of care for individuals with hemophilia in the United States. The US Federal Government recently passed health reform legislation with several provisions to transform the way health care is delivered and how health care services are paid, promote value, and reward high quality of care. This article describes, in economic terms, the cost of hemophilia and how it is determined by measuring direct, indirect, and total cost; a summary of the cost of hemophilia is derived from a review of the recent literature and other published reports and abstracts. Limitations of the current cost-of-illness (COI) literature are explained, and the methodology used to measure quality of life and how it is used as a tool in economic evaluation and outcome assessment in hemophilia are discussed. Finally, some of the issues in health care reform and how these may affect consumers and providers in the care of individuals with hemophilia in the future are presented.

Measuring COI

COI studies measure the economic burden of a specific disease by quantifying the total opportunity cost of all goods and services consumed or foregone in the course of the illness and treatment. (Opportunity cost is the value of opportunity forgone. It is strictly the best opportunity forgone as a result of engaging resources in an activity. It recognizes there can be a cost without the exchange of money.) COI analysis assists policy makers and health economists in understanding the burden of illness to individuals and society. In the strictest sense of the term, because no outcome measures are included, COI is distinguished from other economic evaluation, which measures both costs and consequences.5 However, as a cost-analysis method, COI studies provide a framework for cost estimation in cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses.

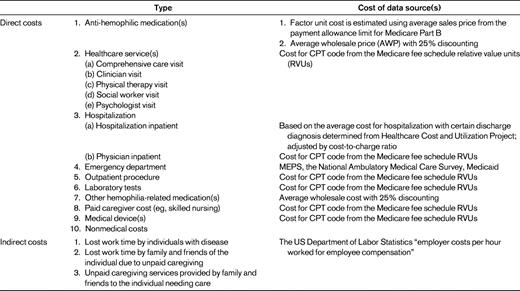

COI measurement is traditionally divided into 2 categories: direct and indirect costs. In addition, COI studies can be undertaken from several different perspectives, each of which affect the type of costs included in the calculation. From a societal perspective, all types of costs, both direct and indirect, should be included. If COI studies are from the health care system, hospital, or third-party-payer perspective, only those direct costs associated with a particular perspective are considered. Table 1 lists all components that should be included in a COI analysis of hemophilia from a societal perspective.

Direct costs

In economic evaluations, direct costs of a disease generally refer to those costs generated by expenditures for medical care and the treatment of the illness and complications. These costs are often thought of as those involving monetary transactions. Direct costs encompass all types of resource use, including hospital inpatient, physician inpatient, physician outpatient, emergency department outpatient, nursing home care, hospice care, rehabilitation care, diagnostic tests, prescription and nonprescription drugs, and medical supplies. Some researchers also include direct nonmedical costs, monetary costs that are not directly related to medical treatment: for example, transportation to and from the clinic and nonmedical home care such as babysitter services.

Direct costs can be easily obtained by surveys and database analysis. Three approaches are often used: the “top-down” approach, the “bottom-up” approach, and the econometric approach. The top-down approach uses aggregated data to calculate the attributable risk of health services use for a disease group, which is then multiplied by the total health care expenditures to estimate the health care costs for that disease group.6 A disadvantage of this method is that it may lead to biased estimates when there are comorbidity and other confounding variables (eg, age or gender).7 The bottom-up approach estimates costs by calculating the average cost of treatment and multiplying it by the prevalence of the disease at the national or regional level.6 The average cost of treatment is estimated by multiplying unit costs of service by the total number of health care encounters for each type of health care service. This bottom-up approach combines unit cost data with utilization data and is useful for less common illnesses. The growing availability of large administrative claims databases and electronic medical databases offers opportunities to study COI using econometric modeling to predict the incremental cost difference between persons with disease and those without disease. However, given the rareness of hemophilia, the “bottom-up” approach is still the most commonly used method in COI studies of hemophilia. Table 1 lists examples of direct costs associated with measurement of the cost of hemophilia.

Indirect costs

Indirect economic costs represent productivity loss due to morbidity and mortality in which no monetary transaction is involved. Indirect costs are nearly always considered in COI studies when the perspective is societal. Indirect costs are of 3 types: (1) lost work time by individuals with disease, (2) lost work time by family and friends of the individual due to unpaid caregiving, and (3) unpaid caregiving services provided by family and friends to the individual needing care.8 Lost work time may be short- or long-term absenteeism, disability, or premature death. Some illnesses, such as depression or multiple sclerosis, may not lead to absenteeism but may cause diminished productivity. The loss of work product due to lowered productivity is also a COI, but this is rarely considered in the analysis because it requires detailed data and measurement of productivity losses.

Three approaches are used to estimate indirect costs: the human capital method, the willingness-to-pay (WTP) method, and the friction cost method. The human capital approach is measured as the foregone wage or salary income of a patient or caregiver as a result of illness.9,10 Wage rates and employment rates are used to calculate the indirect cost, so this approach is easy to implement. However, some groups maybe undervalued if their basic wage is lower (eg, women, the young, and the elderly). The monetary value of indirect cost can also be estimated by the WTP approach.9,11 Individuals are surveyed to determine the amount of money they are willing to pay to reduce the probability of illness or death. But the WTP value may not fully capture the costs of disease and has many intangible costs that are difficult to measure in monetary value, such as pain or suffering. And an individual's WTP is strongly related to his/her ability to pay and risk tolerance. WTP is also more expensive and difficult to implement because it requires survey of impacted individuals. The friction cost method estimates the costs associated with the replacement of a sick worker when hiring and training a new employee.12 This method can more accurately estimate the actual loss of productivity, because the losses are often eliminated after replacement of the former employee. However, it is rarely used because it requires a lot of additional information that is not easily attainable.

Cost of care in hemophilia

Many previous studies of the cost of hemophilia have been conducted in Europe. Although it has been estimated that health care for hemophilia requires approximately 2-3 times the health resources available for the average inhabitant in developed countries, an examination of health care utilization indicates that 20-30 times these resources are actually used.13 For example, in Germany, a country with roughly 6000-8000 hemophiliacs, the average annual cost per individual with hemophilia varies from €40 000 to €120 000 per year.14 The per capita health expenditure in Germany is ∼ €250015 in the general population (in 2007 Euros). The relative proportion of health spending for hemophilia care compared with overall health spending is even higher in developing countries.13

Clotting factor costs account for 45%-93% of the total health care cost for hemophilia depending on severity and treatment regimen.16–18 In a retrospective study by Globe et al, the annual medical cost of hemophilia care was estimated to be $139 102 per person in 1995 US dollars.16 Clotting factor consumption accounted for an average of 72% of total costs, ranging from 45% for mild hemophilia to 83% for severe hemophilia. Higher health care costs were found to be significantly associated with severe hemophilia, arthropathy, a history of inhibitor to factor VIII, and infusion of factor VIII concentrate through a port versus intravenous infusion. In terms of a treatment strategy, clotting factor consumption in prophylaxis has been reported to be 2- to 3-fold higher than that in on-demand treatment.16 More recently, Manco-Johnson et al conducted a randomized controlled trial to compare the clinical outcomes of episodic versus prophylactic factor replacement treatment.19 These researchers found that children at the age of 6 annually received 6000 IU of factor VIII/kg body weight in the prophylaxis group, compared with 2500 IU/kg in the episodic group. Given an average cost of recombinant factor VIII of $1 per unit, the cost of prophylaxis for a child weighing 50 kg could reach $300 000 per year. The number is even higher in individuals with inhibitors treated with immune tolerance therapy.20–22

In addition to direct health care costs, studies have also shown considerable indirect costs related to hemophilia.18 These indirect costs include individuals' and caregivers' lost productivity, caregivers' unpaid time costs, and hemophilic individuals' disability.23 Comparing prophylaxis versus episodic treatment in an 11-year retrospective panel data analysis, Carlsson et al found that the cost of productivity loss in prophylaxis was less than half of that in episodic treatment.24 However, the lower non-factor-related indirect costs did not offset the higher cost of clotting factor for prophylaxis versus episodic treatment. This is because factor concentrate accounted for 77% of the total costs for on-demand treatment and 94% for those on prophylaxis. In this example, the annual total cost (both direct and indirect) for a typical 30-year-old patient with severe hemophilia was €51 832 for episodic treatment and €146 118 for prophylaxis (values are for Euros in the year 2000).23 In the United States, final evaluation of the Hemophilia Utilization Group Study (HUGS) of the direct and indirect costs of hemophilia A is in process, but preliminary data show similar trends to those found in European studies.25,26

HRQoL

Traditional outcome measures of hemophilia care are confined to clinical outcomes, such as number of joint bleeds, arthropathy-associated pain, and loss of range of motion, or utilization outcomes such as office visits, emergency room visits, or hospitalizations. More recently, there is an emerging interest in evaluating health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as an outcome of care for individuals with hemophilia that can inform disease management and policy decision making. HRQoL can be evaluated by interview or by a psychometrically constructed questionnaire. As with any chronic disease, 2 basic HRQoL measures are available: generic instruments and disease-specific instruments.

Generic instruments, which assess HRQoL regardless of disease state, allow comparisons among treatment alternatives and across diseases. The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36),27 the 12-item short form (SF-12),28 and the EuroQol (EQ-5D)29 are the most frequently used generic instruments used for the measurement of HRQoL in hemophilia. Many studies have shown that joint bleeds, arthropathy, chronic pain, and comorbidities have a strong influence on the impairment of HRQoL.30–32 The Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL)33 has been a tool used to study quality of life in children < 18 years of age, including children with hemophilia.26

Although generic instruments provide a common metric with which to compare general HRQoL across diseases, they may not capture the symptoms or impairment related to a specific disease and may not be sensitive enough to detect the differences between various treatment groups or changes over time. For this reason, disease-specific instruments that focus on the specific concerns of individuals with hemophilia have been developed. These instruments include Hemofilia-QoL34 and Hemolatin-QoL35 for adults and Haemo-QoL36 and the Canadian Hemophilia Outcomes-Kids Life Assessment Tool (CHO-KLAT) for children.37

Health care reform and implications for individuals with hemophilia and for health care providers

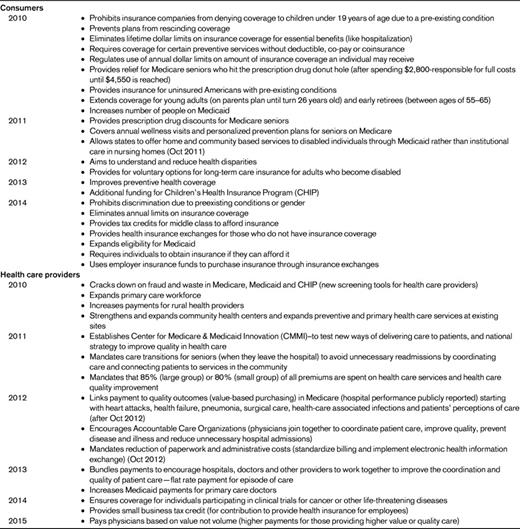

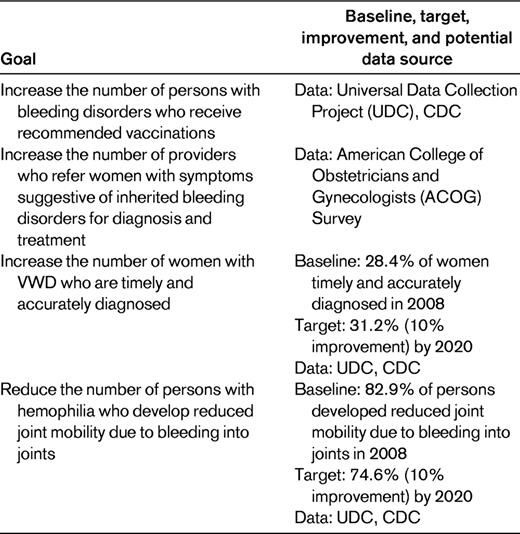

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act, which proposes to increase access to affordable care for all Americans, was signed by President Obama.38 Among the provisions, which will be rolled out based on the timeline noted in Table 2, there are impacts on both consumers of health care and their providers. In addition, Healthy People (HP) 2020, a comprehensive document of national health-related goals and objectives, specifies several national objectives under the topic “Blood Disorders and Blood Safety” that will be targets of efforts to improve the quality of care for individuals with hemophilia (Table 3).39 Under health care reform, initiatives are expanding that require providers in health care delivery systems to become more coordinated through Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) or at a minimum through utilization of electronic records. It is possible that the hemophilia-specific HP 2020 measures of quality may contribute to the standards by which overall health care quality is determined and tied to payments “bundled” to groups of providers and hospitals in the future.

Health care reform timeline and implications for consumers and health care providers38

Healthy People 2020 Objectives: blood disorders and blood safety related to hemophilia39

Health care reform: individuals with hemophilia and their families

For individuals with hemophilia and their families, there are several changes under health care reform that will affect insurance coverage and availability. Because hemophilia is a rare but costly disease, one barrier to accessing health care for individuals with hemophilia is the extent of insurance coverage and the difficulty of finding adequate insurance coverage for adults and for adolescents as they turn 19 to obtain adequate insurance coverage. New data from HUGS-Va examining this issue in individuals with hemophilia A found that 14% of the population studied reported barriers to obtaining hemophilia care. Those reporting barriers to care also more often had no insurance or insurance coverage for < 12 months of the year, were low income, and had difficulty finding insurance.40 In this population, 10% lacked insurance coverage at all or had < 12 months of coverage in a year and 27% had difficulty finding insurance.41 Additionally, in this same study, 24% of children were on Medicaid and 26% on another state program that stops coverage after 18 years of age. Sixty-nine percent of children had private commercial insurance through their parents, coverage that is also limited by age. All of these individuals will benefit by the health care reform changes begun in 2010 or those that will become effective later (Table 2).

In addition to insurance reform, there are several other health reform changes that may benefit individuals with hemophilia. Elimination of lifetime “caps” or dollar limits on coverage for essential benefits, relief for Medicare seniors who hit the prescription “donut hole,” insurance for the uninsured with preexisting conditions, and expansion of eligibility for Medicaid all have the potential to be beneficial to those with hemophilia.

Health care reform: providers of health care

Most of the health care reform issues affecting providers of care to individuals with hemophilia fall into 2 broad categories: (1) changes in payment and insurance coverage expansion for individuals with hemophilia and (2) health care delivery system or organization changes that reward quality and stimulate cooperative, team-based care.

Individuals whose insurance coverage was dropped or limited before reform will now have insurance payment coverage and providers will not have to bill consumers or families individually or provide uncompensated care. Individuals without insurance who previously could not see a doctor will now be covered. This could mean that providers may have an increased caseload. Under reform, there are increased financial benefits for providers located in rural areas, more coverage for preventive care, and stimulation through increased payments for use of primary care providers, some of which may be appropriate in the care of an individual with hemophilia.

A major consideration in health care reform is how to optimally provide care across a continuum of different institutional settings with teamwork and efficiency that promotes the highest quality of care. In 2012, health care reform encourages the implementation of ACOs defined as “a local entity and a related set of providers (at least primary care, specialists and hospitals) that can be held accountable for cost and quality of care delivered to a defined subset of Medicare beneficiaries or other defined populations.”42 Physicians providing care to individuals with hemophilia will need to continue to be involved in hemophilia treatment centers (already similar to ACOs) and perhaps to expand their network to provide care for enrollees in other health care organizations or systems through cooperative agreements. It will benefit all providers of care if there is good management, continuity, cooperation, efficiency, and teamwork in care provision, and organizations must have the capability of measuring the quality of care and value provided by their organizations to maximize payments based on value.

Conclusion

In summary, although physicians are trained to measure outcomes based on clinical measures such as the success of treatment or laboratory value changes, future practice may require the expansion of measures based on economic and humanistic (HRQoL) outcomes. At the same time, health care reform is theorized to increase consumer access or eliminate barriers to care while rewarding providers who are efficient and provide high-quality care. Successful future practitioners under health care reform will need to carefully balance these competing pressures.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.A.J. has received research funding from Bayer, Baxter, Novo Nordisk, CSL Behring, Pfizer (formerly Wyeth), CHOC at Home, Grifols, and Region IX hemophilia treatment centers. Z-Y Zhou has received funding from Baxter Healthcare. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Kathleen A. Johnson, PharmD, MPH, PhD, Titus Family Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Economics & Policy, Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, USC School of Pharmacy, 1985 Zonal Ave, PSC 100, Los Angeles, CA 90033; Phone: (323) 442-1393; Fax: (323) 442-1395; e-mail: kjohnson@usc.edu.