Abstract

Despite the widespread use of highly effective chemoimmunotherapy (CIT), fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains a challenging clinical problem associated with poor overall survival (OS). The traditional definition, which includes those patients with no response or relapse within 6 months of fludarabine, is evolving with the recognition that even patients with longer remissions of up to several years after CIT have poor subsequent treatment response and survival. Approved therapeutic options for these patients remain limited, and the goal of therapy for physically fit patients is often to achieve adequate cytoreduction to proceed to allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT). Fortunately, several novel targeted therapeutics in clinical trials hold promise of significant benefit for this patient population. This review discusses the activity of available and novel therapeutics in fludarabine-refractory or fludarabine-resistant CLL as well as recently updated data on alloSCT in CLL.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) remains an incurable disease, with all patients who require therapy destined to relapse. The relapsed CLL patient population is extremely heterogeneous, ranging from patients who may have had a prolonged first remission to a single agent to those whose disease did not respond to multiagent chemoimmunotherapy (CIT). The prognosis and management of these patients differs significantly based on the nature of the first-line therapy and the quality and duration of remission to that therapy, as well as on other prognostic factors that include cytogenetic abnormalities, in particular 17p and 11q deletions and IGHV mutational status. This review focuses on the fludarabine-refractory population, traditionally defined as CLL that fails to respond or relapses within 6 months of fludarabine therapy,1 and the subgroup that, in addition to those with 17p deletion, continues to present the most pressing clinical problem. Not surprisingly, 17p deletion, which is associated with treatment resistance and very short overall survival (OS),2,3 is significantly enriched in the fludarabine-refractory subpopulation, present up to 50% of the time.4

Frequency of fludarabine-refractory or fludarabine-resistant disease

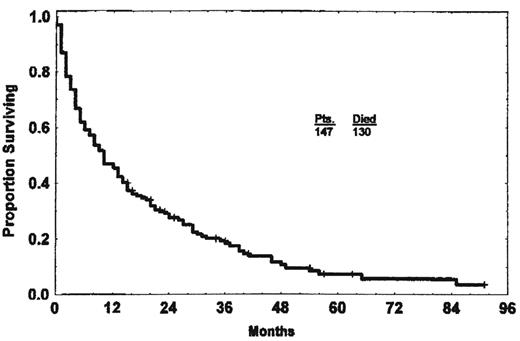

In the era of first-line therapy with single-agent fludarabine, 20%-37% of patients at initial treatment would fit the standard definition of fludarabine refractory.5,6 In an early study of 147 such patients, only 22% responded to their first salvage therapy, and the median OS was 10 months (Figure 1).1 The best response rate of 37% was seen in patients whose salvage therapy included purine analogs with alkylators.1 Since then, as initial CLL therapy has evolved to include these purine analog-alkylator combinations and then, most recently, the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab, the likelihood of refractory disease by the traditional definition has decreased, now 14.5% with FC (fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide) or 7.6% with FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab) in the German CLL Study Group CLL8 trial.3,7 However, in addition to this refractory subgroup, after these more intensive therapies, an additional group of patients still relapse with very short progression-free survival (PFS): 5.6% at 6-12 months after FC/FCR and 14.3% at 12-24 months.7 OS was correspondingly short for all of these patients: 21.9 months for those with PFS < 6 months, 21.2 months for PFS 6- < 12 months, and 47.3 months for PFS 12- < 24 months, compared with median OS not reached for those with PFS > 24 months.7 The subgroup progressing between 6 and 12 months after FC/FCR had a prognosis comparable to the truly refractory group in this study, whereas even those progressing at 12-24 months had apparently reduced OS. Therefore, even with FC or FCR, approximately one-third of patients had significant treatment resistance that was correlated with poor OS; this category included 39% of patients after FC and 23% of patients after FCR. Not surprisingly, these patients were enriched for 17p deletion, which was present in 34% of the refractory group.7

Median OS of fludarabine-refractory CLL is 10 months. (Reprinted with permission from Keating et al.1 )

Median OS of fludarabine-refractory CLL is 10 months. (Reprinted with permission from Keating et al.1 )

These results underscore that even patients who have up to 24-month remissions after purine analog combination therapy are at high risk for poor outcomes and may be appropriately considered for novel or more intensive therapy.8 This observation is further supported by data from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, which reported on 112 patients relapsing after front-line FCR therapy.9 Although the overall response rate (ORR) in this group was 57% to a variety of salvage FCR, rituximab, or alemtuzumab-based regimens, the median OS was only 33 months, and the 5-year OS was 40%. Those patients who relapsed < 36 months after first-line FCR had only a 12-month OS, compared with 44 months for later relapses.9 The data are increasingly indicating that those patients with < 3-year remissions to CIT should not be treated again with the same regimen and should potentially be thought of as more analogous to the true refractory group, to a degree likely dependent on the length of their prior remission. In this review, those patients who do not meet the official definition of refractory because they had an initial response to purine analog–based CIT but then progressed 6-24 months later will be considered CIT resistant. All such relapsed patients should be screened for 17p deletion and, when it is found, these patients should be considered as similar to the true refractory subgroup regardless of the length of their prior remission.8 In addition, Richter's transformation should always be considered in the evaluation of these patients and when clinical suspicion warrants, a biopsy should be obtained, because a finding of transformation would significantly alter the therapeutic approach.

Approach to the CIT-refractory CLL patient

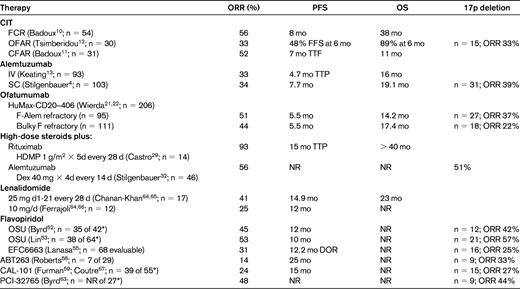

The efficacy of different chemotherapy regimens in truly refractory patients can sometimes be difficult to ascertain from the published literature, because studies often include primarily lower-risk and heterogeneous relapsed patients and do not report the outcomes of the refractory patients separately. Furthermore, single-center studies often obtain promising results that prove difficult to reproduce in a multicenter setting. Many of the currently published studies of CIT regimens in relapsed disease include patients refractory to single-agent fludarabine, rather than to multiagent CIT, likely a higher-risk subgroup. However, a recent report of 284 relapsed patients treated with FCR that did consider refractory patients separately found that those who were fludarabine refractory had a complete remission (CR)/nodular partial remission (nPR) rate of only 8% (ORR 56%), compared with 46% for other patients previously exposed to fludarabine and alkylators.10 In multivariable analysis, fludarabine-refractory disease was a significant predictor of short PFS and OS, along with 17p deletion and complex karyotype, among others,10 leading the investigators to conclude that FCR is most appropriate for fludarabine-sensitive patients with up to 3 prior regimens and without 17p abnormalities. Other regimens with described activity in fludarabine-refractory CLL include CFAR (FCR plus alemtuzumab) and OFAR (oxaliplatin, fludarabine, cytarabine, rituximab), but results are not clearly better than FCR in this group (Table 1).11,12 Therefore, although further therapy with CIT may be a reasonable treatment option for a relapsed CLL population without high-risk features, it is of limited benefit in this high-risk subgroup and is not a preferred option.

Available therapies for fludarabine-refractory CLL

Unless otherwise specified, data provided are specific to the fludarabine-refractory patients; the number of fludarabine-refractory patients in each study is listed in the left column.

*Number of fludarabine-refractory patients of the total reported to date; data are for entire relapsed/refractory study population.

SC indicates subcutaneous; NR, not reported; FFS, failure-free survival; TTF, time to treatment failure; TTP, time to progression; DOR, duration of remission.

Treatment options for CIT-refractory CLL

Given that conventional CIT is not a good option in these patients, alternatives include other approved or available therapies with better activity, stem cell transplantation (SCT), or novel investigational agents (Table 1). For patients who are candidates for SCT, the goal is often to achieve adequate cytoreduction followed by consolidation with reduced intensity allogeneic SCT (alloSCT).

Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) is a humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody (mAb) with significant activity in fludarabine-refractory, alkylator-exposed CLL, the indication for which it was initially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The pivotal registration trial administered alemtuzumab 30 mg IV 3 times per week for up to 12 weeks in 93 patients.13 The ORR was 33% (CR 2%, PR 31%) and the median time to progression was 4.7 months overall and 9.5 months for responders. The median OS was 16 months in the entire study population, but improved to 32 months for responders.13 Major side effects included infusion reactions associated with IV administration and infections. The German CLL Study Group CLL2H trial repeated this study design but administered alemtuzumab subcutaneously, and found comparable results, with an ORR of 34% (CR 4%), a median PFS of 7.7 months, and a median OS of 19.1 months.4 Subcutaneous administration had fewer infusion-related side effects and was more convenient. The CLL2H trial also confirmed prior reports that alemtuzumab induces similar responses and outcomes in patients with and without 17p deletion.4,14 The 8 patients who were able to proceed to alloSCT had the best outcomes in this study, with a 2-year OS of 88%, compared with 27% with other salvage therapies.4

The activity of alemtuzumab in clearing blood and bone marrow (BM) disease is profound, but its effectiveness in lymph nodes > 5 cm is limited. In the pivotal registration trial, the subgroup of patients with at least one node > 5 cm had only a 12% ORR.13 A subsequent study in which heavily pretreated CLL patients continued alemtuzumab until maximum response found that patients with any lymphadenopathy had significantly decreased response and OS compared with those without.15 The outcomes in patients without lymphadenopathy in this study were remarkable: 87% ORR, 72% CR, and 39% negative for minimal residual disease (MRD).15 Long-term follow-up found that the patients with MRD-negative remissions had 66% OS at 72 months and 72% did not require any further therapy.16 This study showed no difference in response between fludarabine-sensitive and fludarabine-refractory patients, and the 8 fludarabine-refractory patients who achieved MRD-negative remission had a median OS of 87 months.16 Other studies have also suggested that longer therapy with alemtuzumab until best response (up to 18-24 weeks if given subcutaneously) may be associated with greater BM disease clearance.17,18 These results suggest that alemtuzumab can be a profoundly effective therapy for even very refractory patients, if they have the correct pattern of disease, namely primarily blood and BM, and the less lymphadenopathy the better. Unfortunately, many fludarabine-refractory patients have significant lymph node disease and their benefit from alemtuzumab is therefore limited.

In an effort to overcome this limitation, combination therapies have been investigated, adding rituximab, fludarabine, FC, or FCR to alemtuzumab. Although reported response rates look encouraging, PFS is generally limited in the setting of fludarabine-refractory disease, and it is unclear that any of these combinations meaningfully overcome the limitations of alemtuzumab in treating lymph node disease. Furthermore, CIT combined with alemtuzumab is potentially quite toxic; a large multicenter randomized trial was terminated early because FC with alemtuzumab led to 6 early treatment-related deaths among 82 previously untreated patients. In that study, the FC-alemtuzumab combination appeared to be similar or less effective than FCR.19

CLL that is refractory to both fludarabine and alemtuzumab (FA refractory) or that is associated with bulky lymphadenopathy > 5 cm, thus making alemtuzumab a poor therapeutic option (bulky fludarabine refractory [BFR]), is associated with a very poor prognosis. The M. D Anderson Cancer Center has reported on clinical outcomes in 99 such patients treated with a wide variety of regimens; the ORR was 23% with no CRs, and the median OS was 9 months: 8 months in the FA group and 14 months in the BFR group.20

Ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a human mAb targeting an epitope composed of both the small and large loops on CD20, distinct from the epitope bound by rituximab. Ofatumumab mediates more potent complement-directed cytotoxicity than rituximab, even at low CD20 expression like that seen in CLL. The results of a planned interim analysis of a large multicenter trial of single-agent ofatumumab in FA-refractory or BFR CLL led to the accelerated approval of ofatumumab for the FA-refractory patient population in the United States.21 In this analysis of 138 patients, the ORRs were 58% and 47% in the FA and BFR populations, with corresponding PFS of 5.7 and 5.9 months and OS of 13.7 and 15.4 months, respectively.21 The final analysis of 206 patients enrolled on this study was presented at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) 2010 annual meeting, with similar results: ORR 51% and 44% in the FA and BFR groups, PFS of 5.5 months in both, and OS of 14.2 and 17.4 months, respectively.22 17p deletion patients with bulky lymphadenopathy responded poorly, however, with an ORR of 22% compared with 49% in BFR patients without 17p deletion, suggesting limited activity in this subgroup. Overall, these results suggest that ofatumumab can achieve a modicum of disease control with symptomatic improvement in a subset of patients,21 but its impact on survival is limited.

Lenalidomide

In a pooled analysis of the 2 initial studies that described the activity of single-agent lenalidomide in CLL, 29 patients who were fludarabine refractory were identified.23 The ORR was 34.5% (10 of 29) with CRs noted in 2 (6.8%) patients. Median PFS was 12-14.9 months depending on the study. Although lenalidomide has been reported to have a 38% ORR in del 17p and 11q patients, this response rate was mostly dependent on the 11q patients, with only one response seen in 17p patients.24 Furthermore, administration of lenalidomide to this patient population can be challenging, requiring initiation at a very low dose and slow escalation to avoid potentially life-threatening tumor flare reactions.25,26 Significant myelosuppression is also often dose limiting; in the final report of the CLL-001 study presented at ASH 2010, 73% of relapsed/refractory patients were unable to escalate lenalidomide above 5 mg/d, and the ORR was 12%.27 These results suggest some efficacy of lenalidomide in this patient population, but poor tolerability in many patients and, again, no long-term control of the disease.23

High-dose glucocorticoid regimens

Glucocorticoids can kill lymphocytes by a p53-independent mechanism and have been studied in CLL, in which they can effectively reduce lymph node disease without severe myelosuppression and appear to be effective regardless of 17p deletion. High-dose methylprednisolone with rituximab has been reported to induce objective responses in 78%-93% of relapsed refractory CLL patients, with 14%-36% CRs.28–30 However the PFS is still short, 7-12 months, and the toxicity high, with a 14% 1-month treatment-related mortality reported in one study,28 and 36% patients developing invasive fungal infections in a second study.30 The activity of this regimen in clearing BM disease is poorly defined, but nodal responses can be significant and can allow patients whose disease burden would have otherwise been prohibitive to qualify for alloSCT.

Given the effectiveness of alemtuzumab in BM disease and glucocorticoids in lymph node disease, the combination has been considered for fludarabine-refractory and/or 17p-deletion CLL patients. An initial published report of 5 patients with 17p deletion or p53 defects treated with high-dose methylprednisolone-alemtuzumab noted 3 CRs, 1 nPR, and 1 PR with this regimen.31 All had significant infectious toxicity, including serious bacterial infections, invasive fungal infection, and CMV pneumonitis. Two of the 5 died at relatively short follow-up, and the others were undergoing MRD monitoring with plans for early intervention upon increasing detectable disease. The United Kingdom CLL206 trial is exploring this regimen in a larger cohort of 17p patients. The German-Austrian-French CLL2O trial is exploring 12 weeks of subcutaneous alemtuzumab with high-dose oral dexamethasone in fludarabine-refractory or 17p CLL, followed either by alloSCT or maintenance alemtuzumab.32 Very early results of the induction phase of the latter study were reported at the ASH meeting in December 2010, and suggested that in 46 fludarabine-refractory patients, the ORR was 56% with 4% CRs, with a median follow-up of 11 months. However, detailed follow-up and toxicity data have not yet been reported.

Treatment options for CIT-refractory CLL: AlloSCT

With the possible exception of alemtuzumab in disease limited to the blood and BM, the regimens described above achieve at best transient disease control in this fludarabine-refractory patient population. Therefore, the primary hope of achieving long-term disease control in these patients is through SCT for those patients who are eligible. Autologous SCT does not appear to have curative potential,33,34 so most attention, particularly in the relapsed setting, has focused on alloSCT. Early studies using myeloablative conditioning regimens have demonstrated long-term disease-free survival in 30%-40% of patients, but at the cost of high treatment-related mortality, often 30%-40% even in relatively young patients.35–37 Most recent work has therefore focused on reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) approaches to alloSCT, in which nonrelapse mortality at 3-5 year follow-up is approximately 15%-30%.38,39

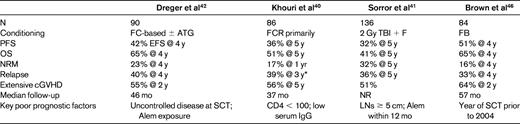

Recent updates of the RIC SCT data from Seattle and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center have both reported 32%-36% 5-year PFS and 41%-51% 5-year OS, respectively, in patient populations who were overwhelmingly fludarabine refractory and heavily pretreated (Table 2).39–41 The recently reported German CLL3X trial enrolled 100 heavily pretreated patients, approximately half of whom were fludarabine refractory, 24% with active refractory disease at time of SCT, and 90 of whom underwent alloSCT.42 The 4-year EFS was 42% and OS 65%. Relapse incidence was 40% at 4 years, which is similar to other studies.40–41 However, those evaluable patients who were alive and without detectable MRD at 1 year after SCT had a 4-year EFS of 89%, with all but 2 remaining MRD negative.42

Recently updated outcomes of RIC alloSCT

ATG indicates antithymocyte globulin; TBI, total body irradiation; FB, fludarabine busulfan; NR, not reported; Alem, alemtuzumab; LN, lymph node.

*Includes some planned immunomanipulation.

These findings suggest that the subset of patients able to attain MRD-negative remission after SCT benefit greatly. A recent retrospective analysis looked at survival among SCT-appropriate CLL patients who actually underwent SCT versus those who didn't due to lack of donor or refusal, and found that the median OS was longer in the SCT group at 113 months compared with 85 months for controls, calculated from the time of diagnosis.43 However, even with SCT, relapse remains a significant problem. Key prognostic factors for relapse after RIC SCT include uncontrolled and/or unresponsive disease at SCT, bulky lymphadenopathy (≥ 5 cm), and alemtuzumab exposure either before SCT or used for T-cell depletion during conditioning.41,42,44 It is encouraging that fludarabine-refractory disease and disease with adverse cytogenetics are generally not predictors of poor outcome, suggesting that SCT can overcome these adverse prognostic features if adequate disease control is achieved before SCT. Given the limitations of the available therapies discussed above and the high relapse rate after SCT, the best way to mitigate these risk factors may still be to use SCT earlier in the disease course, when better cytoreduction can often be obtained.

Alternative SCT strategies should also be considered. A retrospective paired European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) study compared RIC HSCT patients with matched patients receiving myeloablative conditioning and found that, as expected, nonrelapse mortality was reduced in the RIC HSCT patients, but this benefit was offset by an increased relapse rate, such that EFS and OS were equivalent in the 2 groups.45 At the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we have recently looked at the outcomes of our CLL SCT patients between 1998 and 2008 based on conditioning intensity, specifically myeloablative or RIC (Table 2).46 A significant improvement in OS was noted since 2004, which was found only in the RIC group. In the myeloablative group even in the recent 2004-2008 period, nonrelapse mortality remained very high at 47% at 4 years, whereas for RIC in that same period, nonrelapse mortality was only 10% at 4 years. Relapse was not significantly increased in the RIC group (20% vs 8% in myeloablative, P = .17). Because of these findings, OS was significantly better for RIC in the 2004-2008 period, 83% versus 45% at 4 years (P = .001), with a favorable PFS of 69% at 4 years.46 These results suggest that RIC remains the procedure of choice, and that outcomes may continue to improve.

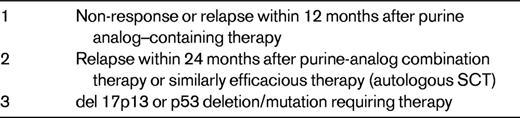

Given the accumulating data showing favorable outcomes for high-risk CLL patients undergoing SCT, several years ago, the EBMT proposed criteria for selecting poor-risk CLL patients for alloSCT (Table 3). These include no response or early (< 12-month) relapse after purine analogs, relapse within 24 months after purine analog–based combination CITs or autologous SCT, or 17p deletion or p53 abnormalities.47 Recent data suggest that p53 mutation confers a poor prognosis similar to 17p deletion, justifying its inclusion in the criteria.48,49 As described above, the data support these criteria, particularly as SCT becomes safer over time. Nonetheless, as yet there are no controlled comparative trials of SCT and standard therapy in CLL, and without such data the precise impact of alloSCT on disease course cannot be definitively determined. The German CLL Study Group has an ongoing prospective trial designed to validate the above criteria, with biological randomization in the 2 highest-risk groups and statistical randomization between SCT and conventional therapy in the lower-risk group (relapse < 24 months after CIT).50 These results will be eagerly anticipated.

Treatment options for CIT-refractory CLL: novel therapies

Recently, several highly active targeted drugs have been shown to have significant activity in relapsed or refractory CLL, including fludarabine-refractory CLL. Although not yet approved, some of these drugs appear to have the potential to control even refractory CLL for an extended period of time (Table 1). If this potential is realized, these therapies may become a viable alternative to SCT, and selecting the timing of SCT may become even more complicated than it already is.

Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors: flavopiridol

Flavopiridol is a pan-inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, including CDK9, that potently induces apoptosis in primary human CLL cells.51 Despite remarkable preclinical activity, initial clinical studies of flavopiridol failed to demonstrate activity due to high levels of protein binding resulting in insufficient free drug concentrations. A pharmacokinetically derived dosing schedule was developed in which the drug was administered as a 30-minute IV bolus followed by a 4-hour continuous infusion.52 Encouraging efficacy was seen initially in a phase 1 trial, which was then confirmed in a phase 2 trial.52,53 In the combined data, 116 CLL patients with a median of 4 prior regimens were treated, 70% of whom were fludarabine refractory. The ORR was 47%, with a median PFS of 12 months, and 9 patients were able to proceed to RIC SCT who otherwise would not have.52–54 However, these results did come at a high cost: life-threatening tumor lysis syndrome was the dose-limiting toxicity in the phase 1 study and required very careful management, including immediately available hemodialysis.52 An international multicenter phase 2 study has recently completed accrual in fludarabine-refractory patients and an initial interim analysis was reported at ASH in 2010.55 Of 113 patients in the intent-to-treat population, 68 were evaluable after at least 2 cycles of therapy, with an ORR of 31% by National Cancer Institute 1996 (NCI-96) criteria and a duration of response of 12.2 months. Toxicity was significant, with grade 3 or greater toxicities including 19% tumor lysis syndrome, 32% infection, and 17% diarrhea.55 Originally planned as a registration trial, this study is no longer accepted as such by the FDA, and as a result, clinical development of flavopiridol by Sanofi-Aventis has been suspended and the future of the drug is unclear. Other related CDK inhibitors are also showing promise in clinical trials, in particular SCH727965, which appears to have a similar response rate but somewhat less toxicity, still causing tumor lysis but less diarrhea and fatigue.56

BCL-2 inhibitors: ABT-263

ABT-263 is a small-molecule BH3 mimetic that potently inhibits BCL-2, BCL-xL, and BCL-w and is able to induce apoptosis in primary CLL cells in vitro with a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of 4.5nM.57 In dog models and in the phase 1 clinical trial when the drug was given on a 2 week on, 1 week off schedule,58 thrombocytopenia due to peripheral destruction of platelets was observed, likely due to specific inhibition of BCL-xL in platelets. This effect peaked at 3-5 days after drug initiation, showed partial recovery while the drug was continued, and resolved when the drug was stopped. However, the same pattern occurred repeatedly at each reinitiation of drug. Because of the recurrence pattern, the dosing schedule was changed to a 1-week low-dose 100 mg lead-in, followed by continuous dosing at 250 mg daily, which mitigated but did not prevent the thrombocytopenia. The phase 1 trial was recently completed, with half of the 29 patients treated on the punctuated schedule and half on the latter continuous schedule.58 The patient population had a median of 4.5 prior therapies and 31% were fludarabine refractory; 90% showed at least a 50% decrease in absolute lymphocyte count, and the ORR was 31%, all PRs. The median treatment duration was 7 months, with median PFS and time to progression of 25 months, so many patients were able to derive prolonged benefit from ABT-263. Furthermore, the PFS was similar in fludarabine-refractory and fludarabine-sensitive patients, suggesting activity in this high-risk patient subgroup. Thrombocytopenia remained the primary significant toxicity and may ultimately limit the use of ABT-263 in heavily pretreated fludarabine-refractory CLL patients. Combination studies have been initiated and ABT-199, a related drug that is a specific inhibitor of BCL-2 only, and therefore unlikely to cause similar thrombocytopenia, will soon begin clinical trials.

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors: CAL-101

CAL-101 is a specific inhibitor of the delta isoform of PI3K. The delta isoform has expression restricted to hematopoietic lineages, and the knockout mouse has a phenotype primarily affecting B-cell function. CAL-101 has been studied in a large phase 1 study in hematologic malignancies, which enrolled 192 patients and closed to enrollment in early 2011. Fifty-five patients with CLL were enrolled in this study59 ; 71% were refractory to their most recent prior regimen, 82% had bulky lymphadenopathy, and the median number of prior therapies was 5. Dosing was continuous and oral in arbitrary 28-day cycles. Early in the study, an interesting phenomenon was observed: patients showed rapid symptomatic improvement concomitant with marked lymph node shrinkage, but their lymphocyte counts often rose initially. This rising lymphocytosis would generally stabilize in the first 2 cycles and then decline in a subset of patients. This constellation of findings, namely symptomatic improvement, nodal shrinkage, and rising lymphocyte count, suggested that CAL-101 was inducing redistribution of CLL cells from lymph nodes or BM into the peripheral blood, a phenomenon that had been noted previously with a SYK inhibitor60 and the mTOR inhibitor everolimus.61 For the purposes of the study, a decision was therefore made to consider discordant response, namely lymph node shrinkage with increased lymphocyte count, as stable disease. Ultimately, all CLL patients in that study showed lymph node shrinkage, with > 80% showing at least 50% reduction. Initially, 58% of patients showed a > 50% increase in their absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), although many of these ALCs subsequently declined. The ORR by International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (IWCLL) 2008 criteria was therefore 24% and was similar in the refractory patients and the 17p patients.59 Because of the observed pattern of response, however, the response rate does not fully capture the clinical benefit: the median number of cycles was 9, and the median PFS 15 cycles. Twenty-one patients have completed the planned 12 cycles and were continued on therapy in an extension study, with preliminary results suggesting that those patients have remained on therapy for a median of 17 months ranging up to 24 months (A Yu, personal communication). CAL-101 has generally been well tolerated, with a 24% incidence of grade 3 or greater pneumonia and a 18% incidence of grade 3 or greater neutropenia, both of which are common in this heavily pretreated CLL population. An asymptomatic grade 3 or greater transaminitis can occur at weeks 4-8 of therapy and was seen in 5% of CLL patients; most patients were able to continue drug at a lower dose. CAL-101 has been clinically beneficial and well-tolerated in refractory high-risk CLL patients for up to 2 years of therapy, raising the possibility that it could be continued for long-term maintenance therapy. The dose selected for phase 2 studies is 150 mg twice a day,59 and combination studies have been initiated.

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors: PCI-32765

PCI-32765 is an irreversible covalent inhibitor of BTK, a B-cell receptor associated tyrosine kinase that is required for B-cell development and function. Initial results of this drug specifically in CLL were reported at ASH 2010, in which patients were treated on a 28 days on/7 days off schedule as well as a continuous dosing schedule.62 The phase 1a study enrolled 16 CLL patients with a median of 3 prior therapies, and reported data with a median follow-up of 8.3 months; very early data on 38 patients from the phase 1b/2 study were also included, with a median follow-up of 1.8 months. Interestingly, the same pattern of response was observed as with CAL-101, with a lymph node response of > 50% in 87% of 39 patients, accompanied by an increase in the ALC. The response rate at 2 months follow-up was therefore 25%, with an additional 53% nodal responses with lymphocytosis, whereas at the 8-month follow-up, the response rate had improved to 70%, with 15% nodal responses with lymphocytosis.62 These results suggest that over time as the lymphocyte count declined, patients were increasingly reaching PR. More mature results of the phase 1b/2 study were reported at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2011 annual meeting.63 Patients were enrolled in 2 cohorts: previously untreated over 65 years of age, or relapsed/refractory with at least 2 prior therapies. Thirty-nine patients of the 78 enrolled were evaluable for response. Relapsed/refractory patients had a median of 3 prior therapies. Nodal response was seen in 89% of patients with lymphadenopathy, with an increase in ALC in 75%. At a median follow-up of 4 months, the ORR was 44% (39% PRs, 5% CRs) and 4 of 12 patients with deletion 17p had responded, suggesting activity in this subgroup. Toxicity has been generally minimal and primarily gastrointestinal, with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, and fatigue. Myelosuppression has not been seen. Therefore, similar to CAL-101, PCI-32765 is a very promising novel therapy with excellent disease activity and minimal toxicity to date.

Conclusions

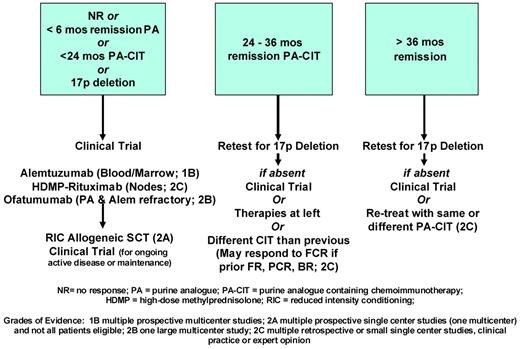

CLL that is resistant or refractory to fludarabine or purine analog CIT remains a major clinical problem with few standard therapeutic options (Figure 2). The choice of therapy depends primarily on the duration of prior response and the presence of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities. For the highest-risk patients, including those with true refractory disease and/or 17p deletion, the goal of therapy is to induce remission and to proceed to RIC alloSCT for those patients who are candidates. Fortunately, for those patients who are not candidates for SCT or whose disease does not respond adequately, novel targeted therapies currently in clinical trials appear to have substantial activity with little myelosuppression, even in this highest-risk patient population, and are well tolerated for potentially long durations of therapy. These drugs may soon lead to significant improvements in our standard therapeutic options for refractory CLL/SLL. Nonetheless, RIC alloSCT currently remains the only curative option, and as SCT outcomes continue to improve, must be strongly considered whenever feasible.

Schematic of management of relapsed CLL based on duration of remission and cytogenetics. The highest-risk group is at the left, and all patients with 17p deletion are in this group regardless of prior remission duration. The middle group is intermediate and the right group is at lowest risk.

Schematic of management of relapsed CLL based on duration of remission and cytogenetics. The highest-risk group is at the left, and all patients with 17p deletion are in this group regardless of prior remission duration. The middle group is intermediate and the right group is at lowest risk.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the patients who participate in our research studies as well as the clinical and research staff who make them possible. I am grateful to John Byrd, MD, for critical review of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.B. has served as a consultant for Calistoga Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacyclics, and Celgene and has received research funding from Celgene, and Genzyme. Off-label drug use: Off-label use of lenalidomide is discussed herein.

Correspondence

Jennifer R. Brown, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Director, CLL Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Mayer 226, Boston, MA 02215; Phone: (617) 632-4564; Fax: (617) 582-7909; e-mail: jbrown2@partners.org.