Abstract

Integrative medicine (IM) has become a major challenge for doctors and nurses, as well as psychologists and many other disciplines involved in the endeavor to help patients to better tolerate the burden of toxic therapies and give patients tools so they can actively participate in their “salutogenesis.” IM encompasses psycho-oncology, acupuncture, and physical and mental exercises to restore vital capacities lost due to toxic therapies; furthermore, it aims to replenish nutritional and metabolic deficits during and after cancer treatment. IM gains an ever increasing importance in the face of the rapidly growing number of cancer survivors demanding more than just evidence-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. IM has to prove its value and justification by filling the gap between unproven methods of alternative medicine, still used by many cancer patients, and academic conventional medicine, which often does not satisfy the emotional and spiritual needs of cancer patients.

There are, in fact, two things: science and opinion. The former begets knowledge, the latter ignorance.

This sentence was written by Hippocrates more than 2000 years ago in a time when evidence-based medicine was not en vogue but responsible doctors had already claimed that science had to prove whether a medicine would work or was an artefact and possibly toxic. Science at this time consisted not of molecular medicine or prospective randomized clinical trials but was represented by the experienced reality of medicinal procedures that should not harm but benefit the wellbeing of the patient.1

The term “CAM” (Complementary and Alternative Medicine) is generally used as a generic name for “unconventional methods,” distinct from “conventional methods” that characterize the classical type of academic medicine as taught at academic institutions and Universities and practiced in most clinics and in private doctors offices. According to Ernst and Resch,2 the term CAM encompasses “any diagnosis, treatment or prevention that complements mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, by satisfying a demand not by orthodoxy or by diversifying the conceptual framework of medicine.”

If we want to achieve an objective opinion about CAM as it is practiced in the USA and Europe today, we have to try to get as close to the scientific proof of effectiveness and safety as we do for all other so called “mainstream” medicinal procedures. When we do that, we have to realize that there is an astonishing discrepancy between the acceptance and widespread use of alternative and/or complementary methods by cancer patients and the lack of knowledge and/or reluctance of hematologists/oncologists to test or even apply these in cancer care. The reasons are plentiful; the main obstacle seems to be that many alternative ingredients or procedures are based more on opinions than on science and reflect more faith than facts.1

There is, however, mounting evidence for a substantial impact of complementary procedures and some phytotherapies as supportive, auxiliary adjuncts to improve the quality of life of cancer patients and sometimes even increase tumor response.3 Therefore, it is important to separate the objectively helpful complementary entities from the often dangerous and nearly always expensive alternative and unproven remedies and procedures!

More and more the term CAM has become an amalgam of unproven alternative methods and useful supportive measures used by many doctors to strengthen and reconstitute the self-healing capacity of cancer patients who are weakened by chemo-radiotherapy. Therefore, most academic institutions now tend to use the term “Integrative Medicine” (IM) to describe activities complementing modern strategies of academic medicine.

An important aspect of IM in parts of Europe, especially in Germany, is the philosophy of giving incentives and practical help to the patient to detect, realize and mobilize his/her own individual resources of self-defense and resistance to the adverse effects of anticancer therapy. Gerd Nagel, a German oncologist, has created a continually growing movement among oncologists and cancer patients in Germany and Switzerland called “Patients’ Competence”4 that aims to find the “doctor in the patient,” as Paracelsus defined it centuries ago. The patient subjectively wants to understand his/her illness, seek ways of self-healing-power—“salutogenesis” —in the opposite. The physician is interested in the “pathogenesis” of the disease, objectifies the disease process and the host response, and often does not meet the psychological and spiritual demands of the patient. Paracelsus visualized a better understanding between patient and doctor, when both recognize a complementary reality of experiencing the disease, when the treating doctor speaks to the “doctor in the patient.”

Definitions

Integrative Medicine

Integrative Medicine constitutes methods, practices and ingredients used as supplements or complements to conventional, so-called academic medicine. These include psycho-oncology, physical exercise, massage, acupuncture, music or painting therapy, Qi-gong or Tai-Qi, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) methods, teas, minerals or other nutrition additives. Most of these methods have been evaluated for their efficacy and benefit for the patient; many are still under clinical investigation. Providers of these methods do not claim curative effects but rather additive beneficial psychological strengthening or physical or biological restoration.

Alternative Medicines

Alternative Medicines are unconventional methods used instead of conventional medicine as curative, palliative or supportive treatments. Most of these methods, practices or ingredients are considered unproven or of questionable efficacy and toxicity. Proponents often reject scientifically based testing or proclaim their own, sometimes obscure principles of attesting benefits for the patients. Most of these remedies are extremely costly and used over long periods of time. In Germany-Austria-Switzerland, 40% to 80% of cancer patients use alternative medicine besides or (less frequently) instead of conventional anticancer therapy.5 Doctors often are not informed about these “side medications.” Most procedures or drugs are not paid for by the insurance companies, and patients spend a great deal of money on practitioners who are arguably “quack doctors.”

There is, however, in Germany and Switzerland a historically based strong and sometimes nearly fanatical alternative medicine movement whose proponents do not acceptor even actively fight—mainstream academic medicine and often tend to distract patients from curative treatments, denying their benefits or exaggerating their toxic side effects. Operational interaction and intellectual discourse with these alternative groups is difficult, if not nearly impossible, since they do not accept or apply the commonly used scientific methods of testing and proving clinical efficacy and toxicity, nor are they interested in the investigation of the basic principles of biochemical or molecular interactions. They have their own system of communication within their circles, use their own specific nomenclature, rules of clinical assessment, interpretation of results, and statistical evaluation and publish exclusively in their own publication media outside the general scientific community.

Unfortunately, around 50% to 60% of cancer patients in Europe seem to use remedies of these alternative “healing prophets,” often without the knowledge of the treating oncologist, and sometimes interrupting or even secretly replacing the ordered medicine.5

Europe and CAM

CAM was the general term for alternative and integrative medicine in Europe and is still used in official political agendas. The scientific community tends to use the term “Integrative Medicine” for the complementary part of the CAM. We must acknowledge the following facts in Europe:

an increasing use of CAM in cancer patients

lack of objective and authoritative information on CAM

an astonishing lack of knowledge about CAM among oncologists

missing data about efficacy and safety of CAM

a growing need for an open and constructive dialogue

an urgent need for objective and independent information on CAM

a need to gain critical appraisal of medical evidence for CAM

In May 1997, the European Parliament in Strassbourg adopted a resolution on the status of non-conventional medicine in Europe by stating, “. . . nevertheless, the assembly believes that a common European approach to non-conventional medicine based on the principle of patients’ freedom of choice in health care should not be ruled out.” The resolution called the Commission of the European Union to:

Launch a process of recognizing non-conventional medicine.

Carry out a thorough study into the safety, effectiveness, area of application and the complementary or alternative nature of all non-conventional medicines with a view to their eventual legal recognition.

Draw up a comparative study of the various national legal models to which non-conventional medical practitioners are subject.

In formulating European legislation . . . make a clear distinction between non-conventional medicines that are “complementary” in nature and those that are “alternative” medicines in the sense that they replace conventional methods.

From 2002 through 2005 the European Commission, within the 5th framework of the “Quality of life and management of living resources” program, supported an initiative under the heading of a “Concerted Action for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Assessment in the Cancer Field” (www.cam.cancer.org).6

The objectives were to:

Create an European authoritative network around CAM in cancer with experts in CAM research.

Perform medical literature reviews.

Develop patient support and information.

Estimate scientific evidence by literature reviews and information for CAM in cancer.

Produce and disseminate suitable evidence based information for the patient-doctor dialogue.

A consortium of eight Cancer Expert Groups from different European countries worked together to create a website (www.cam.cancer.org) with information for health professionals about CAM and tools for online collaboration for project partners. The consortium initiated systemic reviews as Cochrane Guidelines and installed CAM summaries on specific questions and remedies in use all over Europe. Some examples of the reviews are CAM summaries on acupuncture for nausea and pain; Breuss cancer cure; cannabinoids; galavit; green tea for cancer prevention; laetrile; mistletoe; and massage.

The Present European Situation

The funding for research on CAM was active from 2002 to 2005 in the 5th European Framework for Research. In 2009, however, there was no allocation for research on CAM in the 8th European Framework for Research budget. The short funding period of 2002 through 2005 and the work of the consortium had little effect on the distribution of information, and there was hardly any increase of knowledge on CAM efficacy and safety in the general population. There is still a remarkable discrepancy between the strong inclination of cancer patients to use alternative remedies and methods and the astonishing ignorance and lack of knowledge, as well as interest, of hematologists and oncologists in gaining more insight on CAM, or even in uncovering the reasons why patients tend to use the “green” remedies of Hildegard von Bingen or are inclined to test and taste the offerings of traditional Chinese or Indian medicine.

As in the USA, hematologists/oncologists in Europe are educated to question or at least be cautious with diagnostic or therapeutic strategies or procedures that are not evidence based or fail to offer a plausible explanation of why they should work. With a progression-free survival rate of 97% in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma in localized stages, it is now pivotal to de-escalate therapy, find the treatment with the least acute and long-term toxicity, and consider complementary methods to reconstitute the health status of the patients as soon as possible to the status before the diagnosis. With the balance shifting from the focus on patients undergoing cancer treatment to the increasing cohort of cancer survivors, IM becomes a major challenge for hematologists/oncologists and doctors to become more sensitive to and interested in the psychosomatic and spiritual needs of patients, as well as their hopes for self-attained “salutogenesis.”

Examples for Basic Research Initiatives in Integrative Medicine

For centuries in Europe and in Asia, herbal medicine was within the domain of traditional medical practice for most diseases. Today, Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology are investigating traditional folk medicines around the world for new sources of medicinal plant extracts or herbs that might be effective against viral infections and as anticancer agents.7 There is increasing activity in renowned research centers such as the German Cancer Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg to investigate natural products and ingredients of the traditional Asian medicines, eg, from China or Vietnam.8 Thomas Efferth, a scientist from the DKFZ in Heidelberg describes his work as follows:

“Natural products provide a rich source for developing novel drugs with anti-leukemia activities. The Natural Products Branch of the National Cancer Institute (USA) has collected and tested over 100,000 natural extracts of plants and invertebrates.9 The vast experience of traditional medicines (eg, Traditional Chinese Medicine, or TCM) may facilitate the identification of novel active substances. This approach has been successful. Camptothecin from Camptotheca acuminata represents only one outstanding example for such compounds derived from TCM.10 Considering the severe limitations of current cancer chemotherapy, it would be desirable to have novel drugs which are active against otherwise resistant tumor cells.” He continues:

“In 1996, we started a research program on the molecular pharmacology and pharmacogenomics of the natural products derived from TCM.11 This project became fruitful for the identification and characterization of compounds with anti-tumor and anti-viral activities. Apart from artemisinin and its prominent semi-synthetic derivative artesunate which are both approved drugs,12,13 we have analyzed cellular and molecular mechanisms of several other chemically characterized natural products derived from TCM, eg, arsenic trioxide, ascaridol, berberine, cantharidin, cephalotaxine, curcumin, homoharringtonine, luteolin, isoscopoletin, scopoletin and others.”14

Other examples of applied European IM research are investigations into molecular targets; tumor-angiogenesis inhibition with the green-tea constituent epi-gallo-cat-echin; research on free-radical-catch-chain using vitamins C and E and gluthatione; and, mostly in Germany and Switzerland, laboratory experiments with proteolytic enzymes and mistletoe.3,15 These proteolytic enzymes have a number of putative actions including anti-inflammatory; growth inhibition; inhibition of metastatic spreading; modulation of cell-adhesion molecules; and inhibition of platelet aggregation. Translational research of these agents is still in an early stage, and most data are yet unpublished.

Clinical studies with mistletoe, mainly performed in clinics following the theories of Rudolf Steiner, the creator of anthroposophy, a specific branch of alternative medicine in Germany and Switzerland, lacked scientific accuracy and results generally were inconclusive for many years. In recent years, however, CAM researchers have become acquainted with common good clinical practice (GCP) standards used in other academic randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and there is now mounting evidence for a trend of benefit for mistletoe extracts Iscador and Helixor as additives to conventional anticancer therapy with respect to quality of life, better tolerance for chemo-radiotherapy, and in some studies even a marginal improvement of survival.3,15

Why Do Patients Use Alternative Medicine?

Globally around 50 billion Euros are spent every year for alternative procedures and remedies. The question arises: why do patients want to use alternatives or additives to their generally accepted conventional medicine? The answers are not easy and plentiful: Healthy people want to prevent illnesses, especially cancer, and want to stay young and healthy. Some cancer patients expect a higher cure rate, want to relieve side effects of anticancer therapy, want to have control over their lives, want to take an active role in their “salutogenesis,” and want to get better, feel better and live better.

Lighthouse actions for Integrative Oncology: “HausLebensWert“ in Cologne/Germany

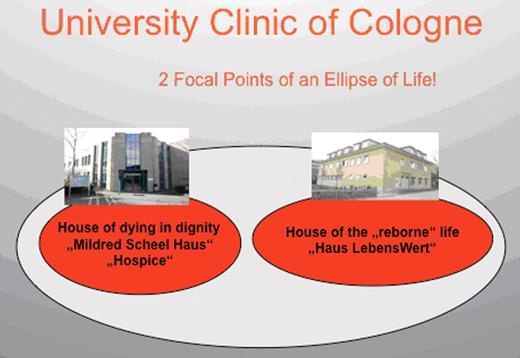

Through its Quality of Life Studies, the German Hodgkin Study Group became more aware of the dichotomy between the perceptions of cancer patients experiencing their fates existentially, and the more objective academic view of the doctors towards the patient as a subject in a randomized clinical trial. We realized that the unfulfilled needs of patients occur during the times when providers were focused on the fight against the tumor cells, looking at the quantity of life while neglecting the qualitative dimension of the suffering human being. In 1999, when we had already treated nearly 12,000 young patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, we started to collect money to build a house for integrative oncology. This lead to the development of the “Haus LebensWert” (the House for a Life Worth Living) (Figure 1 ).

The University Clinic of Cologne already had a hospice for palliative care where cancer patients could die in dignity and peace. The hospice and HausLebensWert together now represent two focal points of an ellipse of life: the hospice for patients dying in peace and the HausLebensWert, the house for the reborn life. The driving forces behind the idea were patient advocacy; the urgent need for psycho-oncology support for cancer patients; and the realization that there was little information for health providers and patients about IM. These forces were combined with an increasing demand around the campus to build a local facility for Integrative Oncology. Patients collected 2.3 million Deutsche Mark in 6 months and built HausLebensWert. The mission statement is “‘Haus LebensWert’ and the ‘Foundation LebensWert’ are dedicated to help cancer patients to get better, to feel better and to live better during and after cancer therapy by offering and incorporating complementary medicine as an integrative part of the cancer patient’s career.”

The institution offers services free of charge to adult patients and their families; it informs, educates and supports patients in coping with life both during the cancer treatment phase and afterwards; and gives suitable information about IM. Available complementary therapies and interventions include psycho-oncology; art-painting-sculpture therapy; gymnastics; physical exercise; music therapy; voice training; Feldenkrais training; Nordic walking; dance therapy; massage and aroma massage; Tai-Qi; Qi-gong and acupuncture. The foundation now has more than 900 members. The staff is paid by the foundation and consists of 11 fulltime, 10 part time and 25 volunteers. The financial support is exclusively from philanthropic donations; no funding comes from the University or social or health insurance companies.

The services have been well received and well used. With about 650 to 700 visits or patient activities per month, HausLebensWert is open for all University clinics treating cancer patients, inpatients as well as outpatients. In addition, private practitioners send cancer patients for the services of integrative oncology at HausLebensWert.

Integrative Medicine: Why Do We Need It?

Academic medicine and modern health care institutions in general may seem anonymous and inhuman, often neglecting the emotional needs of the individual patient. Medical students are focused on evidence-based medicine and trained to measure or calibrate the patient’s disease based on scan results and gene expression profiling. Young doctors strive to get the best possible starting position, either to earn as much money as possible or to achieve the highest impact to earn reputations as famous scientists. On the other side, the cancer scenario is characterized by the growing number of cancer survivors who need psychological and often somatic help to regain a normal life.

IM could be the balance point where cure is complemented by care and ambition mitigated by empathy. IM may become the membrane between the academic world, or macrocosmos, in which the doctor has to function, and the very intimate, often fragile microcosmos of the patient who wants more than just an academically correct diagnosis and state-of-the-art therapy. The patient may also want solace for his soul and acceptance and help for his fears and tears. IM may not offer glory for the doctor, but it may achieve deep satisfaction for the patient. Acupuncture, aroma-therapy, massage, physical or psychological restoration, music therapy and all the attributes that TCM or the other IM instrumentarium can offer, comfort the patient and make him feel that the aggressive anticancer therapy will not destroy his individual gestalt.

To some in our profession, IM may not be the shining stage for health victories or the place to demonstrate a glorious appearance in the community. But in my experience it is the ground where doctor and patient meet as two mountain climbers in a rough region of the rocky mountain path of life! If we want convincing evidence for justification of IM, we have to strive for more visibility in integrated oncology in Europe and the USA. We also should aim for the goals and fulfill the following tasks as much as possible:

Improve information, education and cooperation for IM.

Start IM curricula for students in medical schools.

Initiate CME-IM courses for hemato-oncologists, nurses, and family doctors.

Create academic chairs for IM at universities.

Build multidisciplinary teams for cure, palliation, psycho-social and spiritual support.

Encourage dialogue between conventional medicine and IM doctors.

Improve the clinician’s communication skills.

Develop better tools to measure quality of life, both physical and spiritual.

Acknowledge the patient’s need for spiritual support and facilitate services.

Establish clinical reports that contain modules to document use of IM.

Stimulate open and fact-based discussions on IM between doctors and patients.

For more than 30 years I have been involved in basic, translational and clinical research to find, characterize and defeat the Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells in the laboratory. With the foundation and the 30-year leadership of the Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG), I became a bridge person between science and the clinic. We were able to culture and characterize the tumor cells in vitro, and with the BEACOPP principle we were able to eliminate more than 90% of the tumors in the 15,000 Hodgkin patients we treated in the GHSG. But as a bridgeperson between science and the clinic, I did not realize up until very late in my career that there is another bridge that oncologists have to cross. This bridge has two pillars: one is the objective pillar, the principles of evidence-based medicine. The other is the pillar of the subjective, psychological and spiritual reality of our patients that for a long time went short of being realized in our oncology practice. Integrative oncology means seeing with two eyes: one focusing on the maximal molecular kill of the tumor cells, and the other focused on the suffering face of a human being demanding the most empathy we as doctors can offer.

“Haus LebensWert”: the house of a life worth living for cancer survivors.

Disclosures Conflict-of-interest: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

References

Author notes

Emeritus, First Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cologne, Germany