Abstract

Physician-patient communication encompasses the verbal and nonverbal interactions that form the basis for the doctor-patient relationship. A growing body of research and guidelines development acknowledges that physicians do not have to be born with excellent communication skills, but rather can learn them as they practice the other aspects of medicine. Improvement in physician-patient communication can result in better patient care and help patients adapt to illness and treatment. In addition, knowledge of communication strategies may decrease stress on physicians because delivering bad news, dealing with patients’ emotions, and sharing decision making, particularly around issues of informed consent or when medical information is extremely complex, have been recognized by physicians as communication challenges. This paper will provide an overview of research aimed at improving patient outcome through better physician-patient communication and discuss guidelines and practical suggestions immediately applicable to clinical practice.

I. Recommendations for Breaking Bad News

Anthony L. Back, MD*

University of Washington, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, 1660 S. Columbian Way, Seattle, WA 98108

Many hematologists communicate bad news nearly as often as they aspirate bone marrow. Yet most physicians have had little formal training in communication. A variety of descriptive and interventional studies show that better communication can be described and learned, and that better communication can improve patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. Much of this research has been done in oncology and general medical settings but is clearly relevant to patients with malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases.

How Do Patients and Physicians Experience the Delivery of Bad News?

A useful definition of bad news is that it “results in a cognitive, behavioral, or emotional deficit in the person receiving the news that persists for some time after the news is received.”1 Thus the determination of what news is bad reflects a subjective judgment in the mind of the receiver. Although the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia is clearly devastating, being diagnosed with a hypercoagulable state, hemophilia, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura may be equally earth-shattering to a previously well person.

Patients’ descriptions about their illness experiences are replete with stories of conversations gone wrongand rightand patients repeatedly reflect on the importance of the way these conversations are heldthe setting, the use of words, the nature of the physician’s emotional connection with the patientas being critical to and highly influential on their subsequent adaptation to illness and treatment. Obviously, when the news is good, or the outcomes optimistic, communication specifics may fade more into the background. However, in “high stakes” conversations, such as those that take place around disclosure of bad news, attention to these nuances of communication may help optimize patient adjustment and the partnership that is essential between physician and patient (and family).

Patients report a variety of emotional reactions to hearing bad news. In a study of patients diagnosed with cancer, the most frequent responses were shock (54%), fright (46%), acceptance (40%), sadness (24%), and “not worried” (15%).2 Patient confusion can be an important contributor to the distress commonly seen following a bad news discussion, and the biggest source of patient misunderstanding is technical language. For example, in a study of 100 women who were diagnosed with breast cancer, there was substantial misunderstanding of prognostic and survival information, with 73% not understanding the term “median” survival when it was used by their physician.3 Furthermore, there was no agreement on the numerical equivalent of a “good” chance of survival.

Physicians are not always good at detecting patient distress during bad news encounters, which may negatively affect patient experience. In an intensive qualitative study of 5 oncologists, only 1 of the 5 was able to reliably assess patient distress resulting from bad news. In this study, physician ability to accurately assess anxiety or depression related to a bad news consultation was no better than chance.4 These findings contrasted with the study physicians’ self-assessment of their own performance: they rated their own performance favorably and were highly satisfied with it.5 These data suggest that self-perception of communication skills may be inaccurate, and physicians should pay special attention to external observers of their communication who can be counted on for high-quality feedback.

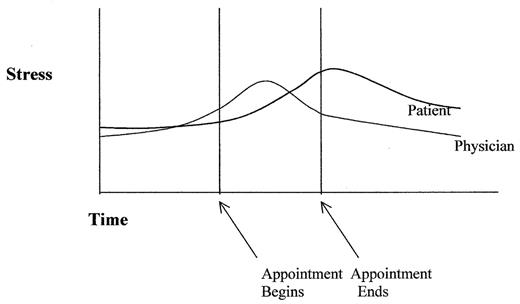

Many physicians experience intense emotions of their own when they communicate bad news to a patient. Ptacek and Eberhardt proposed a model of the stress associated with bad news that relates the physician’s experience to that of the patient (Figure 1 ).1 This model describes the physician’s anticipatory stress before delivering bad news and suggests that physician stress peaks during the clinical encounter, whereas the patient’s stress peaks some time afterward. This stress model can help physicians anticipate the challenges involved in communicating bad news, and some aspects of it have been empirically verified. In a large survey of oncologists, 20% reported anxiety and strong emotions when they had to tell a patients that their condition would lead to death.6 In a more detailed study of 73 physicians, 42% indicated that, despite the fact that the stress often peaks during the encounter, the stress from a bad news encounter can last for hours—even up to 3 or more days afterwards.7 Stress from bad news encounters may interfere with a physician’s ability to address the patient’s needs and may contribute to burnout. Acknowledging this stress and taking active steps to cope—which may be as simple as taking a breather between intense patient encounters—can enhance physician effectiveness in difficult situations and allow the physician to focus on making the experience easier for the patient.

How Competent Are Physicians at Communicating Bad News?

When asked to rate overall physician performance, patients are generally positive but also report that their needs are not always met and their preferences not always heeded during bad news discussions. Among 148 patients with breast cancer or melanoma, about 60% reported “excellent” or “good” satisfaction with how bad news was delivered, although 22% also reported that their doctors seemed nervous or uncomfortable.2 Gaps between what patients want to know and how physicians perform are evident when patients are asked whether physicians discussed the implications of the bad news. In one study of cancer disclosure experiences, only 14% of patients felt that diagnostic disclosure was the most important aspect of a bad news discussion; many patients felt that prognosis (52% of patients) and treatment (18% of patients) were more important. In the patients with breast cancer or melanoma, 57% wanted to discuss life expectancy, although only 27% of physicians actually did this.2 Most of these patients (63%) wanted to discuss the effects of cancer on other aspects of life, yet only 35% reported having these discussions. In another study, patients reported rarely receiving prognostic information.8

Qualitative studies characterize how physician competence in delivering bad news can fall short. In a qualitative study of 79 patients with chronic and terminal illnesses along with 68 family members and health care workers, two issues in physician communication related to bad news had central importance: willingness to talk about dying and ability to give bad news sensitively.9 Poor delivery of bad news stemmed from being too blunt, discussing bad news at a time and place not appropriate for a serious conversation, and giving the sense that there was no hope. Patients also discussed the need for physicians to maintain a balance between sensitivity and honesty in discussing prognosis.10

Studies examining the quality of physician competence in discussing do-not-resuscitate orders and prognosis, issues that may follow bad news, characterize other shortcomings. In an audiotape study of physicians discussing do-not-resuscitate orders with hospitalized patients, physicians spent 75% of the time talking, and missed opportunities to allow patients to discuss their personal values and goals.11 In a study of doctors’ communication of prognosis, physicians reported that even if patients with cancer requested survival estimates, they would provide a frank estimate only 37% of the time and would provide no estimate, a conscious overestimate, or a conscious underestimate most of the time (63%).8 Taken together, these studies suggest that physician competence at communicating bad news is suboptimal.

How Should Physicians Communicate Bad News?

Most patients in the U.S. want to have straightforward, honest discussions with their physicians (and cultural patterns of disclosure are changing throughout the world).12 Patients also want their physicians to be sensitive in these conversations, and they value hope.10 Some patients, however, want basic rather than detailed information.13 In addition, patients and physicians identify a variety of barriers to discussing bad news, and individuals differ on the barriers’ relative importance.14 Thus an approach to communicating bad news that encourages physicians to respond to the needs of individual patients may be more successful than a standardized script, although no comparative evaluations of bad news protocols have been reported.

Several recommendations on communicating bad news were endorsed by a multidisciplinary panel of experts and also rated as “essential” or “desirable” by more than 70% of 100 patients with cancer.15 Many of these recommendations (summarized in Table 1 ) can be found in published protocols for communicating bad news.16– 18

There is no single best way to discuss different aspects of prognosis because patients differ in how they want to hear the news. For instance, among women treated for breast cancer, there was no consensus on whether they preferred a positively framed message (e.g., 43% preferred discussing “chance of cure”) or negatively framed message (e.g., 33% preferred discussing “chance of relapse”).3 Physicians need to inquire whether their communication is satisfying patient needs (“Did that all make sense to you? Is there something else you would like to know about?”) and be ready to reframe information. Because many patients place importance on maintaining hope, it can be helpful to inquire directly (“Many patients tell me that it’s important for them to maintain hope. I wonder if you could say what kinds of things you are hoping for?”).

Recall aids can assist physicians in giving bad news. Audiotapes of the physician-patient consultation have been shown to improve recall of important information and to reduce anxiety in some patients.19 These audiotapes are typically listened to 4 to 6 times after the visit, often by family members or friends who were not present. Similarly, written summaries have also been shown to improve recall of important information, but patients tend to prefer audiotapes.19

It is always difficult to give bad news by phone. Often this situation can be avoided by making arrangements with patients in advance (“If this bone marrow biopsy shows something serious, how should we handle discussing that information? Can we book an appointment now?”). Occasionally, though, the only way to discuss an unexpected finding is by phone, such as when the blood smear reveals blasts after the patient has left the clinic. In these instances, some additional guidelines are helpful:

After you mention that there is important news to be discussed, many patients will want to know the news: acknowledge the difficulty of having the conversation by phone (“I should say that I always find it awkward to have this discussion by phone. I’d rather have a chance to sit down and clearly explain everything to you.”).

Establish that the patient is physically able to have a serious conversation (“Are you in a place where you can talk about this? You’re not driving, are you?”).

Try to minimize the specific details given over the phone (“There are some irregularities in your blood test that we need to discuss. There are several treatment options, but I think it best if you come in so we can discuss this in person.”).

Encourage the patient to bring a support person (“It would be a good idea for you to bring someone with you who can also listen to the discussion and help consider treatment options.”).

Finally, after giving the news, because information from nonverbal cues is not available, make a special effort to ask about how the patient is reacting (“Can you say what your reaction is to all this?”).

Does Competence in Delivering Bad News Make a Difference to Patients?

Physician competence in delivering bad news influences patient anxiety, depression, hope, decision making, and adjustment to illness. In a study of 100 patients with breast cancer surveyed 6 months after surgery, adjustment to illness correlated with physician behavior during the cancer diagnostic interview as well as with a history of psychiatric problems and premorbid life stressors.20 Interestingly, this study indicates that the physician’s caring attitude was more important than the information given during the clinical encounter. In another study, patients who perceived that provision of information was handled poorly during an initial cancer consultation were twice as likely to be depressed or anxious than patients who were satisfied.21 Patients who have concerns that have not been addressed are also more likely to be depressed.22

Bad news discussions also influence patient hope. In a descriptive study, 75% of patients on a hematology-oncology inpatient unit reported that physicians contributed to their hope and that giving information in a sensitive way increased hope. However, because of concern about damaging hope, both patients and physicians may collude to avoid talking about difficult information.23 Similarly, in a study of patients with advanced AIDS, physicians reported that fear of destroying a patient’s hope is one of the most common and important barriers to discussing end-of-life care.14 When physicians want to support patient hopes, and the hopes are realistic, most patients find it very affirming to know that their physicians share their hopes (“I am really hoping that this treatment gets rid of your leukemia.”). When the hopes are not realistic, physicians can still acknowledge patient hopes by using wish statements (“I wish there were another treatment we could use for this kind of relapsed leukemia, but I don’t know of anything of proven value.”). However, it is important to make certain that the patient’s concerns are clearly understood before going on to offer hope, as premature reassurance can block patient expression of fears and concerns.

The link between the delivery of bad news and patients’ subsequent treatment decisions is not entirely clear. However, in a study of seriously ill hospitalized cancer patients, those who unrealistically overestimated their survival were more likely to choose life-prolonging therapy and more likely to die in the hospital after attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation or mechanical ventilation.24 This study emphasizes the effect of inaccurate patient understanding and suggests that improved communication about bad news may influence patients’ choices about life-sustaining treatments.

How Do Cultural Differences Influence Communication About Bad News?

Patients of different ethnic backgrounds vary in their preferences about how to hear about bad news such as a cancer diagnosis. In a study involving European, African, Mexican, and Korean Americans, Blackhall and colleagues demonstrated wide variation in willingness to discuss a diagnosis of metastatic cancer openly.25 However, many of these families address the issue indirectly by focusing on practical logistics.26 Patients from cultures different from those of the physicians may have worse experiences with the delivery of bad news. In one study, nonwhite patients with advanced AIDS rated the quality of patient-physician communication about end-of-life care lower than did white patients with advanced AIDS.27 It may be particularly important for physicians to openly address cross-cultural differences in patients’ preferences about the delivery of bad news.

Some cultures believe that even articulating bad news may be associated with adverse consequences. In a qualitative study of Navajos, Carrese and Rhodes describe how the Navajo concept of hozho (“harmony”) influences communication. Patients and providers should think and speak in a positive way and avoid thinking or speaking in a negative way, which could constitute a dangerous violation of values.28 This view may be more widespread than many realize. In a study of patients with advanced AIDS, Curtis and colleagues showed that African Americans with AIDS were more likely than white patients with AIDS to believe that discussing death could bring death closer.14 These findings indicate that physicians must be alert for situations in which their cultural beliefs and values may differ from their patients’.

Can Communication Skills Be Taught?

Although physicians often assume that communication skills are something that one is born with, a variety of intervention studies show that these skills are indeed teachable. Fallowfield et al reported on an intervention in the United Kingdom that was rigorously evaluated, with videotapes of patient-physician encounters made at each physician’s office before and after a 3-day small group workshop. The resulting videotapes, which were rated by trained coders, show that physicians improved their expressions of empathy, had appropriate responses to patients’ cues, and used fewer leading questions.29 It is worth noting that physicians in this trial were not selected by communication competence—they represented a wide range of competence—and that the persistence of negative communication behaviors in these senior physicians at baseline indicates that communication difficulties are not resolved by time and experience alone. The model of teaching used in this trial has not been widely disseminated in the United States but is a current focus for an ongoing US trial involving fellows.30

Conclusion

Communicating bad news is a fundamental physician skill. Physicians should be aware that their own sense of what constitutes a good encounter may differ from that of many patients, especially when cultural backgrounds differ. These conversations, when handled well, can help patients feel informed and hopeful and physicians feel affirmed in their commitment to care for patients.

II. Communicating with Angry, Anxious, or Depressed Patients

Susan D. Block, MD*

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115

The diagnosis and treatment of cancer is associated with psychosocial distress, vulnerability, and elevated rates of psychological morbidity.1 Life-threatening hematologic disorders and cancers bring with them concerns about the future, uncertainty, questions of meaning and purpose, fears of burdening or being separated from loved ones, and concerns about loss of control. Patients and their families are thrust into new and often frightening and uncomfortable experiences and into relationships with new care providers. Patients are challenged to cope with losses of function and security, changes in body image, and the myriad discomforts that come with diagnostic procedures and treatments. Strong emotional responses are to be expected even when the procedures and treatments are carried out sensitively and skillfully, and indeed failure to observe emotion can be a warning sign that the situation has overwhelmed the coping abilities of the patient.

Yet strong patient emotions can also interfere with physician-patient communication. Patients and their families forge relationships with their physicians through their experiences with and reactions to the physician’s communication style and behaviors. The tasks of clinical communicationinformation sharing, relationship building, and shared decision makingare inevitably stressful and challenging for both patient and physician. Indeed, oncologists who deal with solid tumors regularly report that repeated exposure to fatal illness is one of the most troublesome aspects of the practice of oncology.2 Thus, physicians, too, bring their emotions to clinical communication about serious illness. Physicians’ past personal experiences and the closeness and length of their relationship with the patient, as well as personal attitudes and values, shape their communication behaviors and emotional responses. For example, the longer the physician has known a patient, the less accurate that physician is likely to be in assessing the patient’s prognosis.3 The physician’s understanding of the spectrum of normal and pathological responses to the stress of disclosure of difficult news or information will allow him or her to serve as a “therapeutic agent”—a healing, understanding presence—for the patient, regardless of what medical treatments are offered.4

Communication Challenges as Relationship Problems

This section will review normal and pathological emotional responses to hematologic diseases and suggest techniques to improve physician-patient communication no matter the circumstances. Although it is tempting to view these situations as the patient’s problem (e.g., “The patient is depressed, angry, or anxious.”), communication difficulties in the physician-patient relationship are always relationship problems. Clinicians find these patients challenging because of the feelings they evoke, feelings of helplessness, frustration, confusion, anger, uncertainty, failure, or sadness. The clinician’s capacity to recognize these feelings and to use them as data about the patient enables relationship problems to be turned into clinical successes. Thus, it is essential for the clinician to develop skills to identify problematic responses in the patient and in him- or herself so that difficult situations can be deescalated, rather than inadvertently amplified. Beyond this clinical goal, the physician who can become engaged, rather than enraged or frustrated, by these clinical challenges can learn to enjoy and grow from developing strong and sustaining relationships with a wide variety of patients. Even when psychosocial or mental health providers are involved in the patient’s care, optimal communication between the hematologist and the patient provides the best environment for compassionate and effective medical care.

Types of Communication Challenges

Normal adjustment to life-threatening illness

Clinicians caring for patients with life-threatening illness inevitably encounter distressing emotional responses, such as depression, anger, sadness, and fear, in patients and family members in response to bad news and fears about the future. Usually, however, the responses are temporary and part of the emotional work that is necessary for the patient to come to terms with a new situation. Strong emotions often evoke feelings of helplessness and fear in the clinician. In response to these feelings, physicians may feel that they need to “fix” the emotion or reassure the patient. Often, listening quietly, encouraging the patient to share any worries (“Tell me more about what you are most afraid of with this transplant.”), and expressing empathy and concern (“I am so sorry that your illness has reached a point where we have to begin thinking about hospice care. . . .”) help the patient reestablish emotional equilibrium. The physician’s ability to listen and respond compassionately is a major determinant of patient satisfaction and influences the patient’s subsequent adjustment to the illness.5,6 However, the process of adjusting to distressing news may take days to weeks. During this time, patients are preoccupied with life-and-death issues and with concerns about the meaning of their lives.7 In this phase of adaptation, the physician can be helpful by listening to the patient’s concerns, exploring how the patient has coped with difficult times in the past, reminding the patient of past coping strengths, and reassuring the patient that the situation will feel more manageable as the patient lives with the new situation: “I know that you are feeling very overwhelmed and terrified about what this means. I also can tell you that the feelings you are having now will evolve to a point that you will find them manageable and where the inner resources I know you have will allow you to feel much better than you do now.” During this time of flux, it can be difficult to distinguish pathological depression and anxiety from the normal intense emotional responses that patients experience. In addition, under extreme stress, elements of the patient’s personality (e.g., controlling, highly emotional, guarded, dependent, chronically depressed, prone to feeling entitled to things) may become more pronounced.8 Although there are no hard and fast rules, prolonged and unusually intense distress are usually markers for psychological disturbance. Psychosocial support and exploration, through support groups for interested patients and through contact with psychosocial clinicians, can facilitate patients’ adaptation to their illness.

Depression

Depression can present in a variety of different ways. The patient may appear withdrawn, angry, anxious, irritable, sad, or hopeless. Some patients may readily verbalize that they are feeling sad or downhearted; others, no matter how depressed, will never directly acknowledge it or may call it something else (e.g., nervousness). Depressed patients often see or hear only the negative side of a discussion, seem lost in their efforts to cope, and mention anything from specific disappointments (e.g., “This chemotherapy isn’t working.”) to global hopelessness (e.g., “Nothing could ever work against my leukemia.”).

Patients may be concerned that being labeled as “depressed” will make the hematologist take their physical problems less seriously, or that the doctor will not work as hard to treat their disease. Recent studies suggest that oncologists are frequently inaccurate in diagnosing depression, accurately classifying only 20 of 159 patients with moderate to severe depression, and rating 78 of these patients as having no depression. Overt symptoms of depression (e.g., crying, irritability, sadness) led physicians to be more accurate in their diagnoses; subtle symptoms (e.g., inability to feel pleasure, poor concentration) were less often recognized as being symptoms of depression.9

Other useful clues to the diagnosis of depression are the clinician’s experience of boredom and aversion, or a sense of failure. The physician may feel that nothing he or she does is right, that the patient is “not trying hard enough,” or that efforts to help are not appreciated. All of these responses are potential indicators of depression in the patient. Some clinicians may be reluctant to delve into the patient’s distress because of concerns about aggravating the patient’s misery or about being unable to handle it appropriately. In response to sadness, it may be tempting to “focus on the positive”: encouraging the patient that “it isn’t that bad,” providing false reassurance, ignoring cues to psychological concerns, changing the focus of the discussion, or succumbing to the temptation to provide false hope. These approaches, borne from an attempt to be “kind” to the patient by avoiding difficult issues, run the risk of communicating to the patient that the clinician cannot tolerate listening to the patient’s distress or providing the patient with erroneous information about prognosis.10

Communicating with patients who are depressed poses numerous challenges. Patients are often withdrawn and difficult to connect with, requiring the physician to reach out actively to forge a relationship. Exploring the patient’s feelings (e.g., “Are you feeling sad or downhearted? Could you tell me more about what kind of thoughts and concerns you are having?”) can often engage the patient in looking at his or her feelings and sharing them with the clinician. Asking more about what is causing the feelings is also usually helpful (e.g., “What is leading you to feel so much more discouraged today?” “What do you think might be causing that pain?”). Often patients need encouragement to share these concerns because of fear that they are burdening or distracting the physician. When a patient is reluctant to share more, it can be helpful to recognize the emotion and create an opening for later discussion: “I can see that you are very upset, but I also get the sense that you would prefer to just go ahead and get your treatment today, rather than talking more about it. Maybe after the treatment is behind you, you’ll feel more able to share these concerns with me.” The goal of such conversations should not be to “stop the crying” or “make things better.” Rather, allowing the patient to speak about feelings and concerns and to feel the physician’s presence and interest usually ameliorates sadness and depression.

Strategies for comprehensive assessment and treatment of depressive disorders in patients with life-threatening illnesses are beyond the scope of this article but are well described in numerous publications.11– 14 In general, psychotherapy and medication, offered in combination, are the mainstays of treatment. All patients with suicidal ideation and/or major depression should be referred to a psychiatrist. When access to a psychiatrist is problematic or a patient refuses referral, psychosocial treatment for depression can be carried out by a social worker or psychologist and the hematologist may elect to prescribe first-line antidepressant therapy (usually with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI]). However, the patient should be referred to a psychiatrist if first-line antidepressant treatment is not effective. In addition, the hematologist should refer to a psychiatrist if the patient seems to be getting more depressed or if barriers to disclosure of concerns exist in spite of the physician’s efforts to address them.

Anger

Many patients react with anger to difficult news in the setting of life-threatening illness. Anger in this circumstance is often a response to loss or to threat and serves the purpose of helping the patient to mobilize inner resources to fight the illness. Many factors may contribute to feelings of anger: delays in diagnosis, depression, family conflict, untreated pain, disappointment and hurt in key relationships, feelings of being abandoned by God, frustration at being out of control, difficulties dealing with uncertainty, disappointed hopes, multiple losses, and feelings of being trapped. Although these may be the roots of anger, it may be expressed indirectly. For example, anger at the physician for a delay in diagnosis may mask a patient’s anger at him- or herself for a delay in having the test done in the first place. The stresses of illness and the many frustrations, indignities, and inconveniences of receiving medical care can also incite patients’ anger.

Some patients may express their anger very directly and openly, while others may respond with tight, constricted, and highly controlled efforts to dampen or contain their angry feelings. Anger may seem irrational in its target or out of proportion in its amplitude. Because anger is usually an unpleasant emotion to be around, it can be difficult for the physician to assess the reasonableness of the patient’s emotional response. Even when anger is “appropriate” and “reasonable,” most individuals find it disturbing. This emotional response, in turn, makes it difficult to respond therapeutically and can lead clinicians to inappropriately personalize the patient’s emotional distress and to respond defensively or withdraw. Especially when one is the object of anger, it can be difficult to hear the patient out and to avoid arguing back and making excuses.

When the patient’s anger is appropriate, nonjudgmental listening and acknowledging and validating the patient’s feelings can be therapeutic. Often, if a physician reminds him- or herself that he or she is not responsible and that hearing the patient’s feelings will be helpful, the clinician can listen undefensively to the patient’s expressions of anger. Encouraging the patient to talk about his or her feelings and their sources allows anger to be put into proportion and provides the patient with a connection that also acts as a salve for difficult feelings. As perspective is regained and the patient feels the clinician’s concern and caring, it is not uncommon for other issues, particularly those related to feelings of loss, to come to the surface. When the patient feels heard and understood (e.g., “I can see that you are incredibly frustrated that the IV infiltrated again. I am so sorry that you have to deal with this discomfort and misery.”), anger dissipates. On the other hand, when the clinician responds defensively (e.g., “Look, we are all doing our best. If you had gotten here on time, we wouldn’t have had to rush so much to get the IV in.”), anger usually escalates. When anger seems irrational, it is sometimes helpful for the clinician to reflect honestly about the apparent misdirection or amplification of distress (e.g., “I haven’t ever seen you respond quite this strongly to a delay in the clinic. Do you have any thoughts about what might be different for you today?”). This form of gentle confrontation, particularly when communicated with warmth and appropriate humor, can help the patient regain control and perspective.

In some cases, despite the efforts to listen to and support the patient’s expression of emotion, anger persists. Often, this is a clue that other sources of distress are present. Is the patient depressed or using alcohol or drugs? Are there other sources of distress (pain, spiritual crisis, family dysfunction) that are troubling the patient and are difficult for the patient to discuss? Is the patient someone who characteristically responds to problems with anger? Are there unexpressed problems in the physician-patient relationship (e.g., distrust, feelings of being devalued or not listened to)? Systematic assessment of these domains through direct questioning (e.g., “Do you think that you are depressed?” “Do you notice a connection between your pain and your irritability and anger?” “Is there something that I might be doing as your physician that is getting in the way of our communicating well with each other?”) can often lead to the identification of therapeutic strategies. In rare cases, a patient’s anger may continue to escalate in spite of these efforts. In these circumstances, setting limits on the anger is essential to protect the patient from behaving badly, the physician and other staff from the potential for harm, and the physician-patient relationship from the possibility of rupture. Setting gentle but firm limits, with a commitment to hearing the patient’s concerns at a time when the anger is better controlled, is appropriate (e.g., “I can see that you are becoming more and more angry and that it is hard for us to have a real discussion about why you are so upset. I’d like to understand more about what is going on with you, but I think I could do a better job if you could get your anger under better control. Why don’t you take some time to see if you can get a better grip on the anger, and if you can, we can come back and talk some more about what is going on.”)

Patients who are habitually angry or who show irrational anger that could indicate a psychotic disorder or organic impairment should be referred for psychiatric evaluation. A psychiatric consultation is also indicated when a patient’s anger is frightening clinical staff or appears to be escalating in response to compassionate efforts to explore the patient’s concerns.

Anxiety

Anxiety is a universal response to the uncertainties of life-threatening illness and the threat of death. Anxiety signifies a threat to the person’s well-being and wholeness. Low levels of anxiety (enough to mobilize, not so much that the patient is overwhelmed) energize the patient and spur adaptation and coping with the threat.

Fear about symptoms or the disease, unfamiliar experiences and caretakers, pain, separation from loved ones, and medications (e.g., corticosteroids) can all contribute to anxiety in patients with serious or life-threatening illnesses. Commonly used anti-emetics (metoclopramide, prochlorperazine) can also cause a very distressing motor restlessness. Anxiety symptoms may be an indicator that a major depression or substance abuse disorder is present. Patients with anxiety often tolerate medical treatments poorly or experience amplified responses to medications. Anxiety and fear lead some patients to withhold important information (e.g., about new symptoms) because of fear of what might be uncovered. Finally, anxiety reduces pain thresholds and leads to intensified physical distress.

Patients may demonstrate anxiety in physical symptoms such as sweating, tachycardia, and insomnia as well as in psychological distress. Anxious patients often cannot take in information they have been offered and ask the same questions over and over again. They may overreact to symptoms or treatments, or behave unexpressively and stoically. Their behavior may seem inconsistent and impulsive. They may seek detailed information or not ask reasonable questions. They may be suspicious of the physician’s recommendations or not ask questions because of high levels of fear or regression.

High levels of anxiety tend to amplify the patient’s usual style of coping or personality. Acute stress and anxiety are often a sign that the patient’s psychological defenses are being stretched to their maximum and that the patient is in danger of being overwhelmed by strong feelings. Denial of the illness is an example of an extreme form of anxiety in which the patient is indicating that the reality of the illness is unbearable. The denial serves as a psychological defense, protecting the patient, at least temporarily, from the pain and suffering associated with reality. It is a desperate defense, and one that usually should be supported, rather than challenged, unless the denial is interfering with necessary adaptations and decisions (e.g., a young, single mother who needs to make custody decisions for her child but is unable to do so because of her insistence that she does not really have refractory leukemia). Intense denial is often a marker for depression,15 and its management is best carried out in collaboration with a mental health clinician.

The physician meeting with an anxious patient may become uncharacteristically anxious and uncomfortable. Fidgeting, hedging, and feelings of agitation and tension in the physician are indicators that the patient may be experiencing pathological levels of anxiety. Similarly, the physician’s feeling that the patient might really not be as sick as he or she looks can also be an indicator of the patient’s denial and its impact on the clinician.

The clinician confronted with an anxious patient must first differentiate the extent to which the anxiety represents an acute or subacute response to illness, a true anxiety disorder, or a depression. Anxiety disorders are extremely common: 1-year prevalence rates for anxiety disorders in adults are 16% or more.16 “Normal” anxiety in response to serious illness generally responds well to exploration of fears and concerns, to empathic listening, and to helping the patient evaluate options and develop coping strategies. To differentiate usual anxiety from an anxiety disorder, the clinician might ask the patient: “Are you someone who tends to be nervous or on edge a lot of the time, even before your illness?” “Have you been feeling a high degree of tension and anxiety most of the time lately?” An affirmative answer to these questions suggests that the patient may have an anxiety disorder and is likely to benefit from medication in addition to psychological intervention.

The primary psychological intervention for patients with anxiety is to explore concerns and fears: “When you think about your illness, what are you most afraid of?” “What are you concerned about in hearing that we need to change treatments for your leukemia?” Although the tendency in response to expressions of concern is to immediately reassure the patient (e.g., “No, this doesn’t mean that you are dying, because we have other good treatments for your disease.”), it is usually also helpful to explore the worry further: “I hear that you are afraid that this means you are dying. When you think of that possibility, what things do you worry most about?” Patients generally feel a sense of relief in sharing these concerns and a greater closeness with their physician, which itself further reduces anxiety. In general, patients who are extremely anxious have difficulty processing information and evaluating possible coping strategies. Providing the patient with an opportunity to share concerns and fears often allows him or her to attend better to information from the physician and to jointly develop effective coping responses. For some patients, relaxation exercises (slow deep breathing, muscle relaxation, visualization of a safe and secure place) can help reduce anxiety to a more tolerable level. Cognitive reframing can also be useful: “I know it feels like this chemotherapy is killing your blood cells, but it might be more helpful to imagine it as creating space for healthy cells to thrive.”

Anxiolytic medications are useful for the short-term management of acute anxiety, or for the long-term management of chronic anxiety disorders. Patients whose anxiety does not respond to exploration and/or short-term treatment with anxiolytics and whose functioning is significantly impaired by their anxiety (e.g., patients manifesting denial that is interfering with necessary adaptation) should be referred to a psychiatrist for further evaluation and treatment. Further evaluation for panic disorder, depression, and substance abuse as well as cognitive and psychotic disorders is essential in these circumstances.

Personality disorders and pre-existing psychiatric illness

When the usual strategies for dealing with individuals who pose communication challenges do not work, the clinician should consider the possibility that the patient has a personality disorder or other major psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar illness). These patients characteristically evoke high levels of distress and dissatisfaction in those who deal with them. They may interact in unpleasant ways, behaving manipulatively, demandingly, impulsively, angrily, or disruptively. These individuals have been described as “hateful” patients, reflecting their ability to create ill-feeling in their caregivers.17 Each clinician responds differently to different kinds of patients, depending on the circumstances. For example, an anxious patient with a new diagnosis and detailed and repeated questions about pages of information that he or she has tracked down on the Internet might be particularly troublesome to a clinician who prefers a high degree of control of the clinical encounter. A patient who berates staff and questions their competency while asking for special favors will irk almost every clinician, but the intensity of the clinician’s response and his or her ability to set appropriate limits on the patient’s behavior will be influenced by past experiences with similar persons.

Patients with personality disorders and psychiatric illness require complex treatment strategies. Even the best strategies are frequently ineffective. Often, goals of treatment are constrained by the patient’s psychopathology, and clinicians need to accept limitations on their ability to provide optimal medical treatment. All clinicians managing such patients are helped by having a team, including a mental health clinician, with whom to share the challenges and frustrations of caring for such patients, as well as a safe setting in which to reflect on the personal emotional responses evoked by the patient.

Conclusions

Communication about life-threatening illness is fraught with intense emotions for both patient and physician. An approach to communication difficulties that views challenging communication scenarios as problems in the physician-patient relationship has the potential to strengthen the clinician’s capacity to address the patient’s emotional distress and to respond therapeutically to a wide variety of common clinical challenges.

Summary Points:

Strong emotional responses are normal in the setting of life-threatening illness.

Understanding the spectrum of responses to serious illness allows the physician to support the patient and make appropriate referrals for psychosocial support.

All communication problems are relationship problems. When communication is difficult, the physician should reflect on his/her possible contributions to the difficulties.

Talking about fears, worries, and the impact of the illness on the patient’s life is virtually always therapeutic.

Persistent, unremitting anxiety or depression may represent psychiatric illness; such patients should be referred to a psychosocial clinician for counseling and medication should be considered.

Patients who are angry are usually helped by undefensive listening, which communicates caring, concern, and understanding.

Denial is an extreme response to anxiety and should be considered as a risk factor for depression.

When usual strategies of helping patients deal with emotions (listening, exploration of concerns) don’t work, the clinician should consider the possibility of unrecognized substance abuse or personality disorder. A team approach is often helpful in dealing with such patients.

III. Putting Shared Decision Making into Practice

Stephanie J. Lee, MD, MPH*

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St., Boston, MA 02115

Initial visits to hematologists and oncologists are rarely happy events. Usually there is a serious actual or potential health problem whose diagnosis and management entails additional diagnostic tests, therapeutic procedures, new medications (including chemotherapy), and ongoing monitoring. Many testing and treatment decisions need to be made before a patient and physician have gotten a chance to really know each other and develop a close relationship. In these circumstances, good communication is especially critical to ensure that patients receive the optimal treatment for their particular situations.

It is helpful to divide medical decisions conceptually into two broad categories: problem solving (where there is one right answer, e.g., exchange transfusion for a seriously ill patient with sickle cell disease and acute chest syndrome) and decision making (selecting the best option for this particular patient, e.g., whether a young patient with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia should take imatinib [Gleevec] or undergo early allogeneic transplantation).1 Although many clinical situations blur these categories, the former presumes that the evidence in support of an action is so overwhelming that almost all physicians and patients would agree, while the latter acknowledges either medical uncertainty about the correct option or the necessity of incorporating patients’ values and life priorities to determine the best option.

For problem solving, most patients prefer that physicians go ahead and make decisions, as long as the risks and benefits of the treatment are clearly explained to the patient. Decision making, on the other hand, ideally involves patients early in the process to be sure that decisions reflect both the patient’s values and the physician’s medical knowledge. The most balanced model, “shared decision making,” is a collaborative process in which a patient and a physician consider together both the patient’s values and the advantages of different treatment options, to arrive at treatment decisions. The following section will describe the shared decision-making process, contrasting it with alternative models of treatment choice, and provide a framework for successful implementation of shared decision making.

Different Models of Treatment Choice

Table 2 shows the commonly recognized models of medical decision making. Very few patients today desire the extreme ends of the spectrum (models A and E), where either the physician or the patient is solely responsible for the decision. This situation contrasts with the paternalistic model that was prevalent in medicine up until the 1960s. A 1961 study showed that 90% of physicians preferred not to reveal a cancer diagnosis to a patient, effectively negating the patient’s ability to participate in health care decisions.2 Several influences in American medicine have conspired to shift attention to models of decision making that involve patients more directly. These influences include awareness of informed consent issues, attention to patient autonomy and consumer rights, increasing number and complexity of therapeutic options, and decline in the perception of physicians as all-knowing. Model E, the consumerism model reflects the extreme end of this spectrum, where patients make treatment decisions by themselves and the physician is really providing a service rather than being involved in selecting the treatment.

Two less extreme categories (models B and D) both involve some form of input by physician and patient into the final treatment decision, although one party assumes the majority of the responsibility. In the physician-as-agent model, the physician bears responsibility for making the treatment decision, but only after applying criteria specific to the patient, that is, trying to put him- or herself in the place of the patient, ideally by using personal knowledge of the patient’s values. In the informed decision-making model, physicians provide patients with the medical information necessary to make the decision, but patients process the information and decide on a particular treatment themselves.

In contrast, shared decision making (model C) seeks to educate patients about potential outcomes of treatment options and to engage them fully in deciding which choice is best. Physicians provide medical information germane to the decision, but patients weigh the possible risks and benefits of treatment. It is important to note that shared decision making does not preclude a strong treatment recommendation from the physician based on medical information. It simply acknowledges the collaborative and interactive nature of decision making and the value of patient input regarding whether benefits are worth risks.

Putting Shared Decision Making into Practice

Studies suggest that collaborative decision making does not have to take more time than a standard visit3–,5 and is associated with greater patient loyalty and satisfaction.6 Several authors have published suggestions for putting shared decision making into practice. A synthesis of these recommendations is presented below.7– 10

Establish a conducive atmosphere. Along with allotting the time and creating an environment to encourage shared decision making, clinicians need to project a sense of being interested in patient input.

Elicit patient preferences for information and decision making. Direct inquiry may be the best approach: “Are you the type of person who wants to know everything about your disease, good and bad? Or do you want me to interpret and screen information for you?” Also, “People vary in how much they want to take control of their medical care. Are you the type of person who prefers to make your own decisions, or do you feel more comfortable just following my recommendations? I will support you either way.”

Identify the choice to be made. Patients need to understand the treatment decision at hand: “We need to decide whether to start chemotherapy now or wait until you have more symptoms.” Or, “Now that you’ve completed 6 months of the blood thinning medication, we have to decide if we should continue this or stop, given that you do have a predisposition to forming more blood clots.”

Discuss the patient’s values, concerns, and expectations. Open-ended questions often elicit the most revealing information: “What worries you the most about this diagnosis?” A discussion of the patient’s goals and risk attitudes can begin with, “In dealing with your disease, are you the kind of person who puts a lot of weight on the risks and long-term complications of treatments or are you someone who thinks more in terms of doing whatever is necessary to try to get rid of this disease even if it brings a lot of risks and complications?”

Discuss medical information and confirm understanding. Physicians are always teaching patients about their diseases and treatment options, but most evidence suggests that patients understand and retain little of it. Techniques and pitfalls are discussed below. Whatever the method of information transfer, it is important to ask the patient what he or she has understood: “What is your understanding about your disease and treatment options?”

Share personal recommendations with patients. Shared decision making does not preclude clear recommendations based on your understanding of the evidence. Most patients want to know what you recommend as a physician, and what you would do if you were in their place. However, you should reveal any personal biases. It is also important to encourage patients to seek second opinions and reassure patients that you will not be offended if they decide to ignore treatment recommendations.

Make or negotiate a decision in partnership with the patient. Offer the patient the chance to make a decision: “So, are you leaning toward treatment now or when you get symptoms?” Reluctance to make a decision or lack of enthusiasm for a physician’s recommendation may signal other unaddressed concerns or issues. Direct inquiry (“You seem reluctant to commit to a treatment approach. Please tell me what your concerns are.”) and time may help to reveal these concerns or issues. If the decision is not urgent, allowing patients to think about the options and return for further discussion a little later may be beneficial.

Affirm the patient’s treatment preference and agree on an action plan. Once a decision is made, this should be acknowledged along with the major reasons for the decision: “So, you’ve decided to hold off on chemotherapy for now because you’d like to be sure you feel well for your daughter’s wedding. If your medical condition changes, we’ll readdress the decision.”

Providing Medical Information to Patients

Most patients say they want all available information about their disease and treatment options. Interest in medical information is associated with younger age and higher educational level, often expressed as a need to understand and take action against the disease. Older patients may prefer less information because they do not feel qualified to make medical decisions, they want to worry as little as possible, and they think it is the doctor’s job to advise them.11 However, even patients who are interested in specific information, such as prognosis, may not ask questions.12 Physicians should not assume that patients will automatically verbalize their questions in response to “Do you have any questions?” nor that failure to verbalize reflects lack of interest in answers. Although physicians may be concerned that too much information, particularly discouraging news, causes psycho-emotional distress, a study that audiotaped 335 first-time oncology consultations did not find increased anxiety if patients were given more information about treatment and prognosis.10

Physicians provide medical information to their patients all the time. Yet studies suggest that patients absorb and understand very little of it.13 Siminoff et al audiotaped 100 consultations with women deciding about adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Although 82% of the consultations ended with a treatment choice, the women had a very poor understanding of the treatment risks, benefits, and side effects.14 A brief overview of educational techniques is presented below:

Avoid medical jargon. Technical medical terms and abbreviations are like a foreign language to many patients. Use simple words already in their vocabularies.

Use numbers when they are available. Studies show that people interpret adverbs such as frequent, rare, common, and likely very differently.15 However, physicians should be aware that, in general, people’s numeracy is poor, and many people do not have an intuitive grasp of percentages and fractions.16

Write down key pieces of information. Graphs or other visual aids may help understanding and recall.

Realize that the same information can be interpreted differently depending on how it is presented. Providing prognostic information in the positive (chance of successful treatment) instead of the negative (chance of treatment failure) reflects more favorably on the option.

Be aware that other cognitive biases can affect choices.17–,21 For example, people associate acts of commission (active choices) with future regret. If a medical team recommends that aggressive supportive measures are stopped when recovery is extremely unlikely rather than asking families to state this choice, the burden of decision making can be eased because families are placed in a position of acquiescence rather than initiation.22 Psychologists have identified other cognitive biases, including too many alternatives (people eliminate options for the wrong reasons) and nonlinearity of probabilities (people overestimate the likelihood of low probabilities and place a high value on certain outcomes).

Assess understanding and attention frequently. If a patient is already overwhelmed or anxious, then further information is unlikely to be absorbed.

Understanding Patients’ Values and Priorities

Understanding a patient’s values and priorities regarding the potential risks and benefits of therapies is also critical to shared decision making. Potential problems with physician-led decision making occur if physician and patient values are different. Many studies suggest that patients are more willing to accept toxicity if there is potential benefit than physicians and nurses are, particularly if patients have dependent children at home.23

Acknowledgment that patients are the experts when it comes to what is important to them may encourage participation in decision making: “I am glad to give you my personal recommendation based on my experience with other patients, but I’m not you. Only you can tell me whether this choice seems right for you, or if another path better matches your values and life goals.”

Techniques to Encourage Shared Decision Making

Specific methods to enhance patient participation in shared decision making are outlined below. Most studies have shown these to be nonintrusive, feasible, and effective in increasing patient knowledge and the likelihood that treatment choice matches patient values. Some focus on helping patients clarify their values; others seek to improve information retention or understanding. Still others try to facilitate patients’ participation in shared decision making with their physicians. Most are designed to engage the patient in thinking about the decision outside of the clinical encounter, so that time with the physician can be used as effectively as possible.

Decision aids help to focus the decision at hand and formalize incorporation of a patient’s attitudes with medical information. For example, decision aids often try to integrate information viewed as material to treatment choice: available treatment options, types and probabilities of outcomes, and quality-of-life considerations. Aids may also include examples of other people making decisions, exercises to help clarify values, and guidance in decision making.24,25

Information aids aim to improve understanding and retention of key pieces of medical information pertinent to the treatment decision. These may be general aids (e.g., brochures, videos), personalized aids (e.g., individualized pamphlets, interactive computer-based programs), or records of medical interactions with the patient (e.g., audiotapes of the consultation, summary letters) but the focus is on providing information rather than helping patients think through decisions.26– 29

Participation stimulants may help engage patients in their care. These include question prompt sheets (a list of suggested topics to discuss with the doctor) and written or personal encouragement to ask questions.30– 32

What If Patients Do Not Want to Participate in Decision Making?

Although all patients should be offered the chance to and encouraged to participate in shared decision making, many studies suggest that active participation is not uniformly desired, and this preference too should be respected. Desire for participation may vary depending on the particular medical decision and whether the disease process is viewed as acute or chronic.33 Older patients and those of particular cultures may prefer less control over decision making. Interest in medical information and desire for participation in decision making are surprisingly unrelated.34,35 Strull et al studied 210 patients with hypertension and compared patients’ preferences for information and decision-making autonomy with physicians’ estimates of those preferences. Results showed that physicians overestimated interest in decision making and underestimated interest in information. Qualitative information gleaned from interviews suggested that patients wished to rely on their physicians to make initial decisions about treatment but wanted to play an active role only later, after they had experience with the medications.36

As patients get more ill or the diagnoses grow more serious, less involvement in decision making is favored, although patients still want information and the power to reject physician recommendations.37 There are many reasons why patients or families may prefer to just follow a recommendation despite a physician’s most skillful and inviting approach to include them in decision making. Acutely ill patients have limited physical and emotional resources to successfully weigh the risks and benefits of choices and also less desire to do so when the stakes are higher.38 Fears of regret may be paralyzing: Degner and Sloan note that, “Being freed of responsibility for making treatment decisions can produce an immense sense of relief, with treatment failures becoming the responsibility of the practitioner rather than the patient.”37 The preference to cede decision-making responsibility should be respected. Degner et al studied 1012 women with early-stage breast cancer and found that 15% reported that they had been pushed to have more involvement in decision making than they wanted.39 (The distribution of decision-making preferences for 999 women is shown in Table 2.) Sutherland et al asked 52 oncology patients about their actual and desired roles in decision making; 63% felt that physicians should have the primary responsibility for decision making.34 Dr. Ingelfinger noted in his editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine:

If you agree that the physician’s primary function is to make the patient feel better, a certain amount of authoritarianism, paternalism, and domination are the essence of the physician’s effectiveness. . . . [A] physician who merely spreads an array of vendibles in front of the patient and then says, ‘go ahead and choose, it’s your life,’ is guilty of shirking his duty, if not of malpractice. . . . [H]e must take responsibility, not shift it onto the shoulders of the patient. The patient may then refuse the recommendation, which is perfectly acceptable, but the physician who would not use his training and experience to recommend the specific action to a patientor in some cases frankly admit ‘I don’t know’does not warrant the somewhat tarnished but still distinguished title of doctor.40

What If Patients Make the “Wrong” Decision?

What if patients and families make choices that seem “wrong”? What about the family that wants everything possible done, even when the medical team feels that recovery is impossible? Or the patient who will not take corticosteroids under any circumstances because of fear of facial swelling, leading to the need for more toxic medications? The important thing to remember is that these choices likely reflect more than medical considerations. They incorporate values outside of what the physician considers wise, but they still have meaning to the patient and family. Rather than attack the decision and values itself, a physician can try to work within those values to reach a different decision. Dr. Gawande, a surgeon, writes:

Even when patients do want to make their own decisions, there are times when the compassionate thing to do is to press, hard: to steer them to accept an operation or treatment that they fear, or forgo one that they’d pinned their hopes on.41

Summary

Collaborative decision making combines the expertise of physicians and patients to help them select the best treatment option among several reasonable approaches. Excellent physician-patient communication is essential for effective shared decision making. Physicians offer medical information, statistics, research results, and experience taking care of similar patients. Patients bring their own unique circumstances, values, and life priorities. Ongoing confirmation that the treatment choice remains the best one as circumstances change allows further opportunities for collaboration. Although patients may in fact not want to be the primary decision makers, a sense that physicians value their input is always welcome.

IV. What Patients Hear When Doctors Talk: Understanding the Patient’s Perspective

Susan K. Stewart*

BMT Infonet, 2900 Skokie Valley Road, Suite B, Highland Park, IL 60035 BMT InfoNet has received educational grants from Fujisawa, PDL, Supergen, Genescreen, Orphan Medical, and Baxter Oncology.

When patients are diagnosed with a hematological disorder, particularly one that is life threatening, the mechanisms they normally use to process information and cope with stress are often inadequate. Gripped by fear, anger, and/or depression, patients are often unable to fully comprehend important information that is transmitted to them by medical professionals and put it into proper perspective. Assessing each patient’s coping style, delivering information in a manner consistent with that style, and repeatedly evaluating whether the patient has understood the message being delivered enhance the likelihood that the patient will be fully informed about the diagnosis and treatment options. There is no “one-size-fits-all” method for delivering disturbing news or making medical decisions. However, all patients share a desire for respect, candor, and compassion from health care providers.

How Patients Cope with Disturbing News

Patients diagnosed with a life-threatening hematological disorder feel a tremendous loss of control. Not only has a disease taken control of their body, but they are incapable of resolving the problem on their own. Instead, they must rely on medical professionals, who may be complete strangers, to recommend and carry out various treatment options. This loss of control breeds anger, fear, and/or depression that can interfere with their ability to process important medical information.

Patients react to this loss of control in different ways. Some choose to reassert control over their lives by learning as much as they possibly can about their disease and treatment options. These patients surf the Internet, network with other patients, seek second opinions, and ask probing questions. They do not want information in increments; they want to know all the possibilities so that there are no surprises down the road. They want their physicians to respect them as important, active partners in their care, and they are suspicious of doctors who “sugar-coat” or “talk down” to them as if they were incapable of understanding or learning medical concepts.

Although their desire for candid, thorough information may convey the impression that they are coping well with their diagnosis, the reverse is often true. Some focus their energies on information gathering and analysis in an unconscious effort to avoid dealing with the powerful emotions they feel as a result of their diagnosis.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the patients who are so paralyzed by fear that they avoid learning any more than necessary about their diagnosis and treatment options. These patients are overwhelmed by too much information and sometimes hear only part of an explanation or key in on particularly disturbing words or phrases. They may be happy to rely on a physician to make treatment decisions, or enlist a spouse or friend to learn about their disease and treatment.

How can a physician assess how much information to share with patients at any given time? “Ask,” say patients who have been diagnosed with hematological disorders:

It’s really important for the doctor to start where the patient is. They can do that by asking some questions. Does the patient want lots of information? Is she interested in statistics? Does she want a list of treatment options or a single recommendation? No one model of communication works for every patient.

What Format Works Best?

Verbal communication is the method used most often to convey information to patients about their diagnosis and treatment options. However, verbal communication alone is often ineffective.

Patients need to be ready to hear and process verbal information when a physician delivers it. This is often not the case. The patient may be too overwhelmed emotionally to process more than a fraction of the information that is being delivered, unfamiliar with medical terms used by the physician, or unprepared for the topics being discussed. Although encouraging patients to ask questions is helpful, patients may find the second and third explanation as confusing as the first and be embarrassed to ask for further clarification.

Supplementing verbal explanations with written materials affords patients an opportunity to read and reflect on important information when they are ready to do so, not when the physician is ready to deliver it. Physicians need not develop patient education literature on their own. A number of organizations offer excellent educational flyers, booklets, and videos to patients with hematological disorders and have websites patients can consult for information. Making these resources available to patients and family members can enhance their understanding of their disease and provide information that will help them formulate intelligent questions.

Encouraging patients to tape-record or videotape important discussions can improve their understanding of verbal information. Sometimes patients key in on a word or phrase, take it out of context, and completely misunderstand the message being delivered. Having an audio or video backup of the discussion enables them to double-check their understanding and clarify the message. It also enables them to transmit this information correctly to loved ones.

Whether the format is verbal, print, or audiovisual, the message must be delivered to patients in lay language. Common medical terms such as remission, prognosis, relapse, renal, and CBC may be unfamiliar to some patients. Most publications for the general public are written at a sixth-grade level. When communicating with emotionally distraught patients, clinicians must simplify and/or demystify explanations.

Double-Check the Patient’s Understanding

It is the rare patient who absorbs all the critical information in one sitting. As patients progress through treatment, it is important to repeat explanations and double-check their understanding. Information delivered several days or weeks earlier may not be retained at the time a key procedure takes place.

Open-ended questions such as “Do you have any questions?” may not be sufficient to test a patient’s understanding. Patients may be too tired, confused, or embarrassed to formulate a reasonable-sounding question. Acknowledging that the volume of information you are giving patients can be overwhelming and encouraging them to jot down questions in between visits can give patients an opportunity to have their concerns addressed at the next visit. Communicating this suggestion respectfully is important.

Encouraging patients to ask questions consists of more than telling them that it is all right to do so. Creating an atmosphere where patients feel comfortable communicating their questions and concerns is essential.

For example, the doctor who comes into a patient’s hospital room and sits down while discussing issues with a patient is more likely to convey the sense that questions are welcome, than the doctor who rushes in, communicates what is on his or her agenda, and heads for the door while finishing a final sentence. It is also important to ascertain whether the patient is comfortable asking questions in the presence of others. Some may not want to alarm loved ones but nonetheless have questions or concerns.

No Stupid Questions

“There are no stupid questions” is a powerful message to communicate to patients and their loved ones. Communicating that message requires more than words, however. Helping the patient understand that fears and frustrations are normal, expected, and probably felt by most people in the same circumstances can help ease anxiety and open the door for honest communication about a variety of topics.

Some patients may glean information from sources other than the physician and have questions about topics that seem unimportant to a physician. They may be considering alternative medicine or different diets, or have some misinformation about potential treatment options. Some may have questions about treatment options with which the physician is unfamiliar.

It is important that all of the patient’s questions be addressed honestly and respectfully. Patients need to be told when a physician does not know the answer to a question. Patients have more faith in a physician who admits to not knowing the answer to a question and promises to investigate it, than in a physician who dismisses the question out of hand or ridicules the question. One stem cell transplant survivor noted:

I think the best thing our docs did for us was answer our questions and be sensitive to the amount of info we were asking for. Not everyone wants lots of info. We did, and when we didn’t get it, we felt like they were deliberately hiding things from us. Our docs treated us like we were intelligent, but didn’t make fun of us when we were really dumb!

Put Risks into Perspective

Part of the reason patients become overwhelmed with disturbing medical news is that they are seldom equipped to put the information into proper perspective. Everything a physician says about the disease, prognosis, and treatment options sounds terrible. Without some physician guidance, patients may leave a discussion believing the risk of developing a relatively rare complication of the disease or treatment is as great as the risk of developing a more common complication.

When discussing potential side effects of treatment, it helps to group risks into categories. For example, side effects might be grouped into three categories: those that always occur, those that often occur, and those that seldom occur. Doing so can help a patient to temper his or her anxiety about side effects that are unlikely to occur.

Discussing Pain

Many patients fear pain as much as death. When discussing a disturbing diagnosis or treatment option, it is important to emphasize the steps that will be taken to keep the patient comfortable and pain-free.

The words “pain” and “hurt” mean different things to different people. When discussing potential sources of pain, it is important to use more precise language. Words such as “stinging,” “dull ache,” “pressure,” and “jabbing pain” convey a much better sense of what patients can expect and will ease anxiety when these sensations are experienced. If the terms “pain” or “hurt” are used, the patient may imagine a much more uncomfortable experience than is actually the case, which increases emotional distress.

Many “painful” medical procedures are, in fact, painful for only a portion of the time. When discussing procedures, such as a bone marrow aspirate, with patients, it helps to break the procedure and associated pain into components. Although a bone marrow aspirate is an uncomfortable procedure, the truly painful part lasts only a few minutes. Most patients believe they can endure 2 minutes of pain more easily than 20 minutes of pain, and this can help relieve their anxiety.

Although physicians take pain management for granted, patients do not. Thus, when they hear about potential complications of a disease or treatment, they may envision themselves in great pain. Emphasizing that medications are available to prevent and control pain and encouraging patients to report pain early, before it becomes intense, can relieve patients of this worry. Explaining to patients that pain control is an important part of treatment will encourage them to ask for medication when needed. For example, patients who are gripped by pain may be less able to perform tasks that are important for recovery, such as exercise and eating.

Acknowledging the Psychological Implications of Diagnosis and Treatment Options Is Imperative

It is not intuitively obvious to all patients that the extraordinary stress caused by a life-threatening diagnosis may require extraordinary interventions to help them cope emotionally. This is particularly true of people who have never before needed psychiatric help or counseling. Thus, when they are overwhelmed by powerful anger or depression, the idea of seeking professional help may not occur to them. Instead, they may conclude that they are not coping as well as most people in a similar situation, which fuels their anger or depression.