Key Points

An HBP we identified interferes with hepcidin-mediated ferroportin internalization and cellular iron accumulation.

In an animal model of chronic kidney disease, administration of HBP improved iron and hematological parameters.

Visual Abstract

Iron plays a vital role in hematopoiesis and cellular metabolism as an essential constituent of hemoglobin, myoglobin, and several other proteins. Systemic iron homeostasis is regulated by hepcidin, a peptide hormone. Hepcidin binds to the cellular iron exporter ferroportin to induce its internalization and degradation, thereby reducing iron release from the iron-storage tissues to control serum iron levels. In chronic inflammatory conditions, excessive hepcidin expression is commonly observed. Excess hepcidin inappropriately promotes ferroportin degradation to reduce serum iron level and restricts iron availability for hemoglobin production. This contributes to the anemia of chronic diseases including chronic kidney disease. Therefore, inhibition of excess hepcidin activity can be a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of anemia of chronic diseases. Here we identified a hepcidin-binding peptide (HBP) that functions as a hepcidin inhibitor by a phage display selection. We demonstrated that HBP inhibits the hepcidin-ferroportin interaction to neutralize excess hepcidin, resulting in increased release of iron from cellular storage in both in vitro and in vivo systems. Furthermore, HBP ameliorated anemia of chronic kidney disease by neutralizing excess hepcidin in an animal model. Thus, we present HBP as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of anemia of chronic kidney disease.

Introduction

Iron is an essential nutrient for oxygen delivery, enzyme activity, and cellular metabolism in the mammalian body. Intracellular and circulating iron levels are maintained by the 25–amino acid hormone. Hepcidin is synthesized in hepatocytes and secreted into the bloodstream, where it regulates the levels of the iron exporter ferroportin at the surface of iron-recycling macrophages, duodenal enterocytes, and iron-storing hepatocytes. Binding of hepcidin to ferroportin induces ferroportin internalization and lysosomal degradation. This activity sequesters iron in storage sites and serves as a mechanism to control dietary iron absorption.1,2

Excessive hepcidin expression is commonly observed in chronic inflammatory conditions.3,4 Excess hepcidin aberrantly promotes ferroportin degradation and iron sequestration in tissue macrophages, leading to hypoferremia. Chronic hypoferremia restricts iron availability for hematopoiesis2 and can contribute to the pathogenesis of anemia of chronic diseases.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is prevalent worldwide and emerges after renal impairment. CKD leads to several complications, many of them serious.5 A major CKD manifestation, altered iron homeostasis, results in anemia of CKD (A-CKD). This condition increases morbidity and mortality in patients.6 Mechanisms underlying A-CKD pathogenesis include excess expression of hepcidin, and it is induced by kidney failure.7 Serum hepcidin levels increase in patients with CKD due to inflammation8 as well as decreased renal clearance.9 In this study, we focused on the important role of excess hepcidin expression in A-CKD development. In patients with CKD, the increased levels of hepcidin promote ferroportin degradation and limit iron availability for hematopoiesis, resulting in A-CKD.10 We demonstrate that a hepcidin-binding peptide (HBP) inhibits hepcidin activity and has therapeutic effects on A-CKD in a mouse model.

Methods

Materials

The Ph.D-12 Phage Display Peptide Library kit was purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Antibodies used in this study are listed in supplemental Table 1. Human hepcidin-25 was purchased from the Peptide Institute, Inc (Osaka, Japan). Biotinylated hepcidin-25 and hepcidin-20 were purchased from Bachem AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits used in this study are listed in supplemental Table 2. The Metallo Assay Iron Assay kit LS was purchased from MG Metallogenics Co Ltd (Ohita, Japan). The ABTS [2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] substrate was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Polyethyleneglycol (PEG)–succinimidyl glutarate (N-hydroxysuccinimide-glutaryl PEG; 40 kilodalton) was purchased from NOF Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Capricorn Scientific GmbH (Westport, MA). Other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted.

Cells

HEK293 and COS-1 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. HepG2, a human hepatoblastoma-derived cell line, was provided by the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank. All cells were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Animals

C57/Bl6J male mice (7-week-old) were obtained from Clea Japan, Inc (Tokyo, Japan). Animals had free access to food and water and were housed according to the institutional and government guidelines in the animal facility of Oyokyo Kidney Research Institute, with a 12-hour light-dark cycles and at an average temperature of 22°C. The mouse chow contains iron (290 ppm). All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal research committee of Oyokyo Kidney Research Institute. Normal chow diet was purchased from Clea Japan, Inc.

Identification of peptide amino acid sequence that binds hepcidin

To identify a peptide binding to hepcidin, the Ph.D-12 phage library (1 × 1011 plaque-forming units) was incubated 2 hours with the hepcidin-immobilized plate in Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane]–buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20. After the plate was washed, phage binders were eluted and amplified in cultures of Escherichia coli ER2738 (New England Biolabs). After 4 rounds of panning, we obtained a phage pool enriched in phage clones that bind hepcidin. We then selected 64 clones and sequenced those clones to deduce amino acid sequences of phage-displayed peptides. We evaluated the affinity of individual phage clones for hepcidin by phage ELISA. Among the phage clones, the phage exhibiting the highest affinity for hepcidin was selected, and the amino acid sequence of that peptide was determined. A phage with undetectable affinity for hepcidin was also selected from the phage pool as a control phage. The sequence of the control phage was used as a control peptide for the HBP. The detailed procedures to identify the HBP are described in supplemental Methods.

Peptide synthesis

Peptide harboring the hepcidin-binding sequence was chemically synthesized by Scrum Inc (Tokyo, Japan) using Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography purification. The N-terminal residue of the HBP was acetylated, and the C-terminal residue was amidated. The PEG-conjugated peptide binding hepcidin was designated HBP. A peptide with undetectable affinity for hepcidin was also synthesized as a control for HBP and conjugated with PEG. The PEG-conjugated peptides were used for all ex vivo experiments.

Peptide affinity determination

We performed biolayer interferometry on an ForteBio Octet K2 instrument (Dallas, TX). Briefly, biotinylated hepcidin was loaded on streptavidin biosensors (ForteBio), and the biosensors were dipped into solutions containing HBP for 300 seconds, followed by dissociation for 120 seconds. The data were analyzed using ForteBio Data Analysis 11.1 (ForteBio). Results were then fitted into a 1:1 binding model, and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values were calculated.

Analysis of ferroportin internalization and degradation

Human ferroportin complementary DNA (cDNA) was provided by the Riken BioResource Center through the National BioResource Project of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Agency for Medical Research and Development, Japan. To assess the effects of HBP on ferroportin internalization by hepcidin, COS-1 cells transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein-fusion ferroportin cDNA (EGFP::FPN) were incubated either with media alone, hepcidin (0.5μM), hepcidin plus HBP (5μM), or hepcidin plus control peptide (5μM). Cells were examined by fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX-71), and the number of internalized punctate vesicles containing FPN-EGFP was counted. To assess the effects of HBP on ferroportin degradation, HEK293 cells transfected with FPN-EGFP were incubated with either with media alone, hepcidin (0.5μM), hepcidin plus HBP (5μM), or hepcidin plus control peptide for 3 hours at 37°C. Cells were then pelleted and lysed. Total lysates were then subjected to western blotting (supplemental Methods). Blots were imaged with an ATTO Chemiluminescence Imaging System EZ-Capture II (Tokyo, Japan), using the ECL PLUS detection system (GE Healthcare), and quantified using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Analysis of cellular iron export

HepG2 cells were pretreated with 40μM ferric ammonium citrate for 16 hours and then incubated either with media alone, hepcidin (0.5μM), hepcidin plus HBP (5μM), or hepcidin plus control peptide (5μM) for 3 hours and lysed in buffer A (supplemental Methods). To prepare ferroportin-expressing COS-1 cells, cells were transfected with FPN-EGFP and then sorted by fluorescence-activated sorting (BD FACSAria II). Ferroportin-expressing COS-1 cells were subjected to the previously described experiment without pretreatment with ferric ammonium citrate. Ferritin content in the cell lysates was determined using ELISA kit for human ferritin (Abnova).

Analysis of HBP effects on serum iron levels in an animal model

Mice received a single intraperitoneal injection (100 μL) of either diluent only, hepcidin (90 nmol/kg body weight), hepcidin plus HBP (900 nmol/kg body weight), or hepcidin plus control peptide (900 nmol/kg body weight). Four hours later, blood was collected from the facial vein, and serum iron levels were determined using a Metallo Assay Iron Assay kit.

In vivo analysis of HBP effects on A-CKD

The protocol used to induce A-CKD and analyze HBP effects on A-CKD in a mouse model is shown in Figure 5A. To induce A-CKD, we administered 100 mg/kg body weight of adenine sulfate (AdS) intraperitoneally into mice every other day for 3 weeks by following a previous report with some modifications.11 In a control group, we administered water (solvent for AdS) intraperitoneally into mice. On day 7, mice were randomly divided into HBP-administered group (HBP group) or vehicle-administered group (vehicle group) and treated with HBP or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) for the remaining 2 weeks. The total hepcidin amount was estimated to range from 10 to 15 nmol/kg body weight based on the ELISA data of plasma hepcidin levels in CKD mice (400-600 ng/mL). In the HBP group, 150 nmol/kg body weight of HBP (10 times molar quantity of hepcidin) was injected intraperitoneally into mice once a day every other day. On day 21, blood was collected and used for hematological and biochemical analyses. Red blood cell (RBC) counts, hemoglobin (Hb) levels, and hematocrit were determined by flow cytometry (Fuji Vet Systems, Tokyo, Japan). Plasma iron levels were determined using a Metallo Assay Iron Assay kit. Plasma levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and inorganic phosphorous (IP) were determined by enzymatic methods (Oriental Yeast Co Ltd). Plasma levels of mouse ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and hepcidin were determined using ELISA kits.

Histological analysis of kidney

After blood collection, the kidneys were harvested and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 hours. The paraffin-embedded kidney samples were cut into 7-μm sections. The sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome to assess collagen matrix accumulation. To quantify fibrosis areas, 3 stained areas (magnification ×100) were randomly selected, and CellSens standard software (Olympus) was used to assess the ratio of positively stained areas (blue) to the total area (excluding glomerular, small vena cava, and blood vessels), yielding a value representing the percentage of fibrosis area.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the mouse livers or kidneys using QIAzol (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). mRNA expression was quantified using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Rox (Roche, Pleasanton, CA). The primers used in this study are listed in supplemental Table 3.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise noted. Statistically significant differences were assessed by analysis of variance followed by Tukey multiple comparisons or by independent Student t test for comparisons between 2 groups. A P value <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

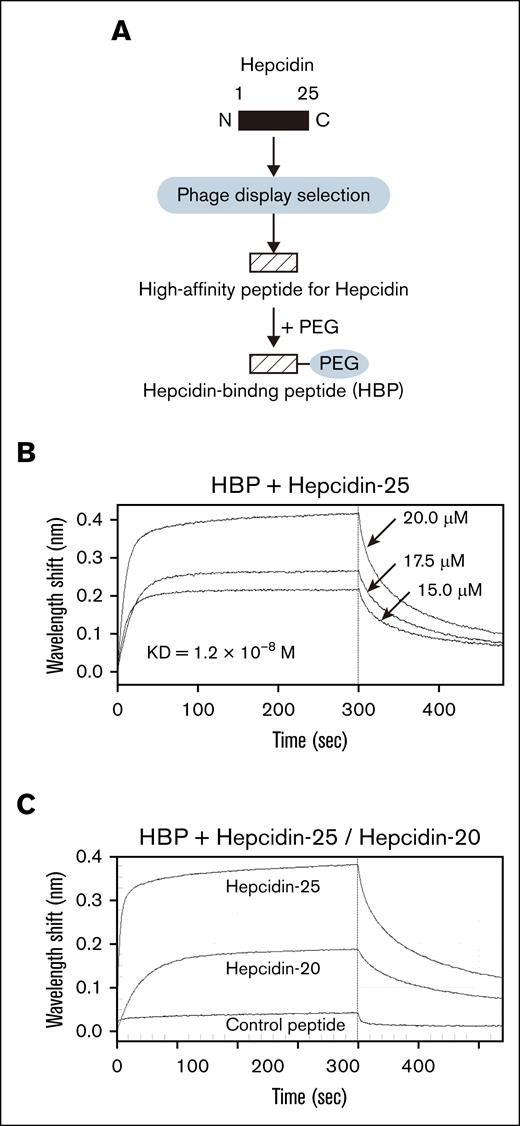

Identification and synthesis of HBP

We isolated the phage clone with the highest affinity for hepcidin after 4 rounds of panning and then synthesized a peptide containing that hepcidin-binding sequence, which we defined as GHWHPRHSIPYK. Database search result indicates that the hepcidin-binding sequence has no homology to known protein domains. The synthesized peptide was conjugated with PEG, and we designated the PEG-conjugated HBP (Figure 1A). HBP did not form any particular secondary structures (supplemental Figure 1). We confirmed the HBP affinity for hepcidin (KD = 1.2 × 10−8M; Figure 1B). PEG conjugation slightly affects the affinity of HBP for hepcidin (supplemental Figure 1). We synthesized a control peptide for HBP (HBP control peptide, HIHWNSAKAKTN) and conjugated PEG to it. We confirmed that HBP control peptide exhibits a very low affinity for hepcidin (KD = 2.8 × 10˗5M; data not shown). The affinity of hepcidin for HBP is considerably higher than the affinity of hepcidin for ferroportin (KD = 10.0 × 10˗8M),12 suggesting that HBP can interfere with hepcidin binding to ferroportin.

Identification and synthesis of the peptide that binds hepcidin. (A) A schema to identify and synthesize a peptide that binds hepcidin. A high-affinity peptide binding to hepcidin was identified using phage display selection and chemically synthesized. The resultant peptide was conjugated with PEG and designated as HBP. (B) Measurement of affinity of HBP for hepcidin by a biolayer interferometry–based binding assay. Biotin-hepcidin-25–loaded sensors captured HBP at concentrations ranging from 20.0 to 15.0μM. Sensorgrams represent 3 HBP concentrations (20.0μM, 17.5μM, and 15.0μM). A sensorgram of a control sample with no HBP was subtracted. (C) Comparison of HBP affinity for hepcidin between hepcidin-25 and hepcidin-20. Biotin-HBP loaded sensors captured hepcidin-25, hepcidin-20, or control peptide at a concentration of 20.0μM.

Identification and synthesis of the peptide that binds hepcidin. (A) A schema to identify and synthesize a peptide that binds hepcidin. A high-affinity peptide binding to hepcidin was identified using phage display selection and chemically synthesized. The resultant peptide was conjugated with PEG and designated as HBP. (B) Measurement of affinity of HBP for hepcidin by a biolayer interferometry–based binding assay. Biotin-hepcidin-25–loaded sensors captured HBP at concentrations ranging from 20.0 to 15.0μM. Sensorgrams represent 3 HBP concentrations (20.0μM, 17.5μM, and 15.0μM). A sensorgram of a control sample with no HBP was subtracted. (C) Comparison of HBP affinity for hepcidin between hepcidin-25 and hepcidin-20. Biotin-HBP loaded sensors captured hepcidin-25, hepcidin-20, or control peptide at a concentration of 20.0μM.

The N-terminal 5 amino acids of hepcidin are essential for its interaction with ferroportin.13 HBP bound hepcidin-20 lacking the N-terminal 5 amino acids but its affinity for hepcidin-20 (KD = 4.4 × 10˗8M) was reduced compared with that for hepcidin-25 (Figure 1C). This indicates that binding of HBP to hepcidin-25 involves its N terminus, confirming that HBP has an ability to interfere with the interaction of hepcidin with ferroportin. The docking model of the hepcidin-HBP complex predicted by HDOCK suggests that HBP interacts with the N-terminal region of hepcidin (supplemental Figure 2), which is consistent with the Figure 1C result (Figure 1C).

HBP neutralizes in vitro hepcidin activity

Hepcidin interacts with ferroportin to induce ferroportin internalization and degradation, thereby sequestering iron in cells.1 We added hepcidin to the medium of FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells and observed the appearance of punctate intracellular vesicles containing FPN-EGFP, indicative of internalized FPN-EGFP1 (Figure 2B). However, incubation with HBP significantly decreased the number of FPN-EGFP–containing vesicles (Figure 2C,E). By contrast, no significant decrease in the number of the FPN-EGFP–containing vesicles in the presence of the control peptide was observed (Figure 2D-E). These results indicate that HBP inhibits hepcidin-induced ferroportin internalization.

HBP inhibits hepcidin-induced ferroportin internalization. (A-D) Immunofluorescence micrographs of FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle high-glucose medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Capricorn Scientific GmbH) and incubated in serum-free medium in the presence of cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) for 2 hours before the experiment. (A) FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells were incubated in serum-free medium with no peptides. (B) FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM). (C) The cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM). (D) The cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus a control peptide (5.0μM). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. FPN-EGFP was internalized, and the punctate intracellular vesicles containing FPN-EGFP were observed. The white arrowheads denote the representative intracellular vesicles. (E) Changes in the number of the FPN-EGFP–containing vesicles per cell. The bars represent means ± standard error (SE; n = 3). ∗P < .05. Cont., control peptide.

HBP inhibits hepcidin-induced ferroportin internalization. (A-D) Immunofluorescence micrographs of FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle high-glucose medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Capricorn Scientific GmbH) and incubated in serum-free medium in the presence of cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) for 2 hours before the experiment. (A) FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells were incubated in serum-free medium with no peptides. (B) FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM). (C) The cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM). (D) The cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus a control peptide (5.0μM). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. FPN-EGFP was internalized, and the punctate intracellular vesicles containing FPN-EGFP were observed. The white arrowheads denote the representative intracellular vesicles. (E) Changes in the number of the FPN-EGFP–containing vesicles per cell. The bars represent means ± standard error (SE; n = 3). ∗P < .05. Cont., control peptide.

Incubation of FPN-EGFP–expressing HEK293 cells with hepcidin clearly reduced FPN-EGFP levels, based on western blot analysis of lysates from treated cells (Figure 3A, lanes 1-2). However, that reduction of FPN-EGFP was suppressed by HBP treatment (Figure 3A, lane 3). Treatment with control peptide had no impact on FPN-EGFP levels (Figure 3A, lane 4). The relative band intensities of FPN-EGFP assayed from 3 independent experiments were used to determine the mean ± standard error (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 3). These results indicate that HBP inhibits the hepcidin-induced FPN-EGFP degradation by inhibiting its interaction with ferroportin (Figure 3).

HBP inhibits hepcidin-induced ferroportin degradation. (A) To assay FPN-EGFP degradation induced by hepcidin, changes in levels of FPN-EGFP in HEK293 cells expressing FPN-EGFP were examined by western blotting. HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% FBS. HEK293 cells were transfected with FPN-EGFP construct and incubated in serum-free medium in the presence of cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) for 2 hours before the experiment. Western blots of cell lysates were assessed for FPN-EGFP (lanes 1-4). Arrowhead indicates FPN-EGFP. Western blots were probed for actin (lanes 5-8) as a loading control. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium with no peptides. Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM; lane 2). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM; lane 3). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus control peptide (5.0μM; lane 4). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. (B) The blots of FPN-EGFP were quantified using ImageJ software. The band intensity with the cells treated with no hepcidin (panel A, lane 1) was regarded as 1.0 for calculating relative band intensities. The relative band intensities from 3 different experiments were used to determine the mean ± SE. cont., control peptide; FPN, ferroportin; WB, western blot. ∗P < .05.

HBP inhibits hepcidin-induced ferroportin degradation. (A) To assay FPN-EGFP degradation induced by hepcidin, changes in levels of FPN-EGFP in HEK293 cells expressing FPN-EGFP were examined by western blotting. HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% FBS. HEK293 cells were transfected with FPN-EGFP construct and incubated in serum-free medium in the presence of cycloheximide (100 μg/mL) for 2 hours before the experiment. Western blots of cell lysates were assessed for FPN-EGFP (lanes 1-4). Arrowhead indicates FPN-EGFP. Western blots were probed for actin (lanes 5-8) as a loading control. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium with no peptides. Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM; lane 2). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM; lane 3). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus control peptide (5.0μM; lane 4). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. (B) The blots of FPN-EGFP were quantified using ImageJ software. The band intensity with the cells treated with no hepcidin (panel A, lane 1) was regarded as 1.0 for calculating relative band intensities. The relative band intensities from 3 different experiments were used to determine the mean ± SE. cont., control peptide; FPN, ferroportin; WB, western blot. ∗P < .05.

HBP inhibits intracellular iron sequestration

For in vitro analysis of iron sequestration in cells, we used HepG2 cells, which express endogenous ferroportin, and examined cellular iron levels by measuring intracellular accumulation of ferritin, a cytosolic iron storage protein. Incubation of HepG2 cells with hepcidin increased cytosolic iron levels (Figure 4A). However, in the presence of HBP, those increases were significantly suppressed, whereas control peptide had no effect on hepcidin-induced changes in cytosolic iron levels (Figure 4A). We obtained similar results in experiments using FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells (Figure 4B). These results show that HBP inhibits hepcidin activity to suppress efflux of ferrous ion from cells. HBP alone (or control peptide alone) had no effect on ferroportin and cellular functions in the above in vitro experiments (supplemental Figures 4-6).

HBP inhibits intracellular ferritin accumulation. (A-B) To assay intracellular iron sequestration in cultured cells, intracellular ferritin accumulation was measured in HepG2 cells (A) and FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells (B). HepG2 cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and nonessential amino acids (Lonza). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus control peptide (5.0μM). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. Bars represent means ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3). ∗P < .05. (C) Intracellular iron sequestration in an in vivo system. Hypoferremia was induced by hepcidin in mice. To suppress endogenous hepcidin, mice were fed a modified AIN-93G rodent diet with no added iron (Research Diet Inc) for 3 days. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of hepcidin, hepcidin plus HBP, and hepcidin plus a control peptide. Peptides (900 nmol/kg body weight) and hepcidin (90 nmol/kg body weight) were separately administered to mice at the same time. Four hours later, the serum ion level was determined (n = 5-7). Comparisons between experimental groups were conducted with the use of multiple Student t tests. ∗P < .05. cont., control peptide.

HBP inhibits intracellular ferritin accumulation. (A-B) To assay intracellular iron sequestration in cultured cells, intracellular ferritin accumulation was measured in HepG2 cells (A) and FPN-EGFP–expressing COS-1 cells (B). HepG2 cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and nonessential amino acids (Lonza). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus HBP (5.0μM). Cells were incubated with hepcidin (0.5μM) plus control peptide (5.0μM). Peptides and hepcidin were simultaneously added to the cell media. Bars represent means ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3). ∗P < .05. (C) Intracellular iron sequestration in an in vivo system. Hypoferremia was induced by hepcidin in mice. To suppress endogenous hepcidin, mice were fed a modified AIN-93G rodent diet with no added iron (Research Diet Inc) for 3 days. Mice received an intraperitoneal injection of hepcidin, hepcidin plus HBP, and hepcidin plus a control peptide. Peptides (900 nmol/kg body weight) and hepcidin (90 nmol/kg body weight) were separately administered to mice at the same time. Four hours later, the serum ion level was determined (n = 5-7). Comparisons between experimental groups were conducted with the use of multiple Student t tests. ∗P < .05. cont., control peptide.

As an in vivo experiment, we intraperitoneally injected C57/Bl6J mice with hepcidin and analyzed their serum iron levels 4 hours later. We observed induction of intracellular iron sequestration, based on decreased serum iron levels (Figure 4C). However, mice injected with hepcidin plus HBP showed no significant decrease in serum iron levels relative to mice injected with hepcidin only. Injection of hepcidin plus control peptide had no effect on hepcidin-induced decreases in serum iron levels (Figure 4C). No significant differences in the mRNA expression levels of endogenous hepcidin and serum amyloid A-1, a marker of inflammation in the liver, were observed during the experiments (supplemental Figure 7A-B). This suggests that the administration of HBP or control peptide does not trigger a short-term inflammatory response to increase hepcidin expression in mice during the experiments. In addition, no significant differences in the serum levels of BUN and creatinine between before and after HBP administration were observed (supplemental Figure 7C-D), indicating that HBP did not affect kidney clearance in this experimental model. Furthermore, we measured the plasma levels of hepcidin 4 hours after hepcidin injection with HBP or control peptide. No significant difference in plasma hepcidin levels was observed between mice injected hepcidin plus HBP and those with hepcidin plus control peptide (supplemental Figure 7E), indicating that HBP did not alter the clearance of hepcidin itself in this experimental model. These results strongly suggest that HBP suppresses intracellular iron sequestration by neutralizing hepcidin activity, thereby increasing iron levels in serum (Figure 4).

Effects of HBP on iron metabolism

To assess the effects of HBP on abnormal iron metabolism seen in CKD, we used a mouse model of adenine-induced A-CKD. We injected mice with AdS intraperitoneally to induce A-CKD (Figure 5A). One week later (on day 7), the plasma level of BUN, an indicator of kidney function, in AdS-injected mice was significantly higher than that in water-injected control mice (control vs AdS-injected mice, 24.6 ± 2.3 mg/dL vs 64.3 ± 18.7 mg/dL; P < .05). The plasma levels of CRP, an inflammatory marker, in AdS-injected mice was also significantly higher than that in control mice (control vs AdS-injected mice, 2.25 ± 0.19 μg/dL vs 5.38 ± 1.82 μg/dL; P < .05). Overall, the increased levels of BUN and CRP indicate that AdS-injected mice develop CKD associated with inflammation. By day 7, plasma hepcidin levels had significantly increased in CKD relative to control mice (Figure 5B white bars), supporting the idea that inflammation is associated with excessive hepcidin expression in CKD mice.11,14 Blood ferritin levels correlate positively with iron storage levels.15 By day 7, we observed significantly higher ferritin levels in CKD mice than control mice (Figure 5C white bars), whereas plasma iron levels were significantly lower in CKD mice than control mice (Figure 5D white bars). These results indicate that excessive hepcidin expression induced by inflammation increases levels of iron stored in tissues and decreases serum ion levels (Figure 5B-D white bars) by day 7. AdS-injected CKD mice exhibited significantly lower RBC counts (Figure 5E white bars), Hb levels (Figure 5F white bars), and hematocrit than water-injected control mice (Figure 5G white bars). Overall, assessment of both hematological and biochemical data suggests that decreased serum iron levels promoted by excess hepcidin secretion cause A-CKD in AdS-injected mice by day 7 (Figure 5B-G, white bars).

Effect of HBP on iron metabolism in A-CKD in a mouse model. (A) Experimental schema used to induce A-CKD in mice and assess the effects of HBP on A-CKD. The schema details the time of AdS injection and HBP (or vehicle) administration. On day 7, A-CKD mice were randomly divided into vehicle-administered group (gray arrow) and HBP-administered group (black arrow). Mice in both groups were treated for an additional 14 days. (B-H) To assess the effect of HBP on A-CKD, the following biochemical and hematological parameters were determined in the control group (n = 5) and AdS-treated group (n = 6) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 6) and HBP-administered group (n = 7) on day 21: plasma levels of hepcidin, ferritin, iron (Fe), and EPO; and the hematological parameters RBC count, serum Hb levels, and hematocrit. Values represent means ± SD. ∗P < .05. HCt, hematocrit.

Effect of HBP on iron metabolism in A-CKD in a mouse model. (A) Experimental schema used to induce A-CKD in mice and assess the effects of HBP on A-CKD. The schema details the time of AdS injection and HBP (or vehicle) administration. On day 7, A-CKD mice were randomly divided into vehicle-administered group (gray arrow) and HBP-administered group (black arrow). Mice in both groups were treated for an additional 14 days. (B-H) To assess the effect of HBP on A-CKD, the following biochemical and hematological parameters were determined in the control group (n = 5) and AdS-treated group (n = 6) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 6) and HBP-administered group (n = 7) on day 21: plasma levels of hepcidin, ferritin, iron (Fe), and EPO; and the hematological parameters RBC count, serum Hb levels, and hematocrit. Values represent means ± SD. ∗P < .05. HCt, hematocrit.

On day 7 after AdS injection, we randomly divided A-CKD mice into vehicle (PBS)–administered group (vehicle group) and HBP-administered group (HBP group) and then treated them with vehicle or HBP for 14 more days (Figure 5A). On day 21, both vehicle and HBP groups showed comparable and higher hepcidin levels than those seen on day 7 (Figure 5B). Although the vehicle group showed higher plasma ferritin levels on day 21 than on day 7 (Figure 5C gray bar), the HBP group showed no increase in plasma ferritin levels in the HBP group on day 21 compared with day 7 (Figure 5C black bar). By contrast, plasma ferritin levels in the HBP group were significantly lower than those seen in the vehicle group (Figure 5C gray and black bars). Plasma iron levels significantly decreased in the vehicle group on day 21 relative to day 7 (Figure 5D gray bar). We observed no decrease in plasma iron levels in the HBP group on day 21 compared with day 7 (Figure 5D black bar); instead, these levels were significantly higher than those in the vehicle group (Figure 5D gray and black bars). These results show that HBP administration in A-CKD mice decreases intracellular iron sequestration and concomitantly increases plasma iron levels, even in the presence of elevated hepcidin levels (Figure 5B-D). These findings suggest that excess hepcidin worsens abnormal iron metabolism between days 7 and 21 but that HBP administration suppresses the worsening of abnormal iron metabolism by blocking hepcidin activity (Figure 5B-D).

HBP suppresses A-CKD progression

To determine whether hepcidin inhibition by HBP could have therapeutic effects against A-CKD, we performed hematological analyses of mice from the vehicle group or HBP group on day 21. On day 21, A-CKD mice from the vehicle group showed significantly lower RBC, Hb, and hematocrit than that seen on day 7, indicating that AdS injection exacerbates A-CKD between days 7 and 21 (Figure 5E-G gray bars). However, on day 21, A-CKD mice from the HBP group showed significantly higher levels of RBC, Hb, and hematocrit than vehicle group mice, despite the fact that hepcidin levels were high in both groups (Figure 5B,E-G black bars). In the HBP group, these hematological parameters were comparable on days 21 and 7 (Figure 5E-G). Although AdS injection and HBP administration have an influence on iron metabolism (Figure 5B-D), we detected no difference in plasma erythropoietin (EPO) levels among control, AdS-injected, vehicle-administered, and HBP-administered mice (Figure 5H).

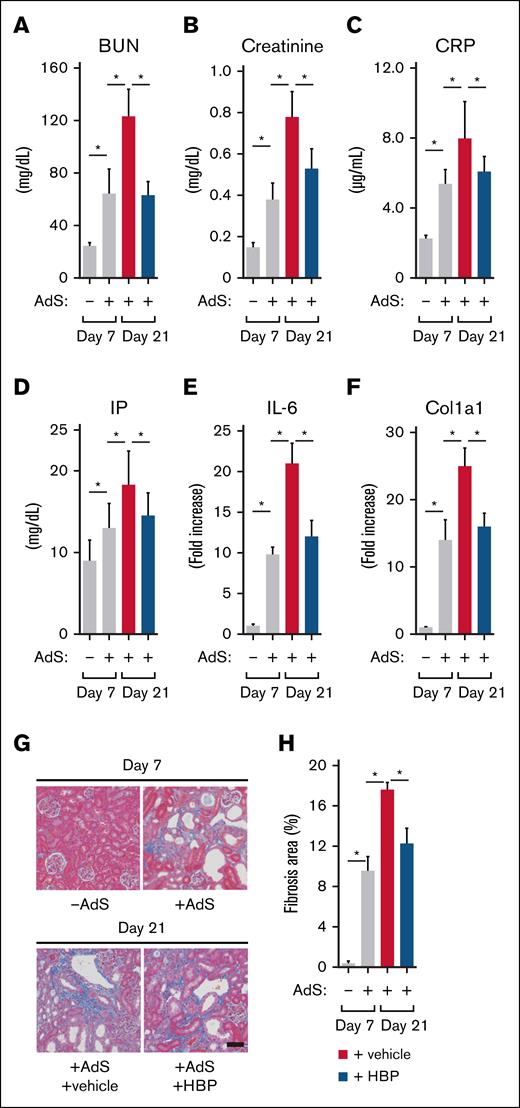

Effects of HBP on kidney fibrosis

We assessed HBP effects on kidney function. On day 21, A-CKD mice from the vehicle group showed significantly higher BUN, creatinine, CRP, IP, and interleukin-6 expression in the kidney than that seen on day 7, indicating that AdS injection impaired kidney function and progressed inflammation in the kidney between days 7 and 21 (Figure 6A-E gray bars). However, on day 21, A-CKD mice from the HBP group showed significantly lower levels of BUN, creatinine, CRP, IP, and interleukin-6 expression in the kidney than vehicle group mice (Figure 6A-E black bars). These results suggest that HBP administration blocks hepcidin activity to restore hematopoiesis by increasing serum iron levels, controlling the exacerbation of kidney function and progress of inflammation (Figure 6A-E).

Effect of HBP on fibrosis in CKD mice. (A-E) To assess the effect of HBP on kidney functions and inflammation in A-CKD mice, plasma levels of BUN (A), creatinine (B), CRP (C), and IP (D) were determined in the control group (n = 5) and AdS-treated group (n = 6) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 6) and HBP-administered group (n = 7) on day 21; expression levels of IL-6; E) were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and the transcript expression was normalized to that of β-actin in the control group (n = 3) and AdS-treated group (n = 3) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 3) and HBP-administered group (n = 3) on day 21. (F-H) To evaluate the effect of HBP administration on fibrosis in A-CKD mice, expression levels of Col1a1 were determined (F) by quantitative RT-PCR (normalized to β-actin); kidney specimens from the control group and AdS-treated group on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group and HBP-administered group on day 21 were processed for Masson’s trichrome staining (G), with representative images of the specimens from each group shown; and Masson’s trichrome staining was quantitatively analyzed (H). The percentage area of kidney fibrosis was calculated by evaluating 3 random fields per section. Data were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < .05. Col1a1, collagen-1a1; IL-6, interleukin-6.

Effect of HBP on fibrosis in CKD mice. (A-E) To assess the effect of HBP on kidney functions and inflammation in A-CKD mice, plasma levels of BUN (A), creatinine (B), CRP (C), and IP (D) were determined in the control group (n = 5) and AdS-treated group (n = 6) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 6) and HBP-administered group (n = 7) on day 21; expression levels of IL-6; E) were determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and the transcript expression was normalized to that of β-actin in the control group (n = 3) and AdS-treated group (n = 3) on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group (n = 3) and HBP-administered group (n = 3) on day 21. (F-H) To evaluate the effect of HBP administration on fibrosis in A-CKD mice, expression levels of Col1a1 were determined (F) by quantitative RT-PCR (normalized to β-actin); kidney specimens from the control group and AdS-treated group on day 7 and the vehicle-administered group and HBP-administered group on day 21 were processed for Masson’s trichrome staining (G), with representative images of the specimens from each group shown; and Masson’s trichrome staining was quantitatively analyzed (H). The percentage area of kidney fibrosis was calculated by evaluating 3 random fields per section. Data were expressed as means ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < .05. Col1a1, collagen-1a1; IL-6, interleukin-6.

We next assessed HBP effects on kidney fibrosis in CKD mice. On day 21, A-CKD mice from the vehicle group showed significantly higher mRNA expression level of collagen-1a1, a main component of the fibrotic extracellular matrix, than that seen on day 7, indicating that AdS injection progressed fibrosis in the kidney between days 7 and 21 (Figure 6F gray bars). However, on day 21, A-CKD mice from the HBP group showed significantly lower levels of collagen-1a1 expression in the kidney than vehicle group mice (Figure 6F black bars). In addition, we assessed the effects of HBP on tubulointerstitial fibrosis by histological analysis of mouse kidney. Masson trichrome stains collagen blue to highlight fibrosis area in tissue sections, representing adenine-induced tubulointerstitial fibrosis. We observed markedly increased interstitial fibrosis in A-CKD mice on day 7 compared to control mice, based on Masson’s trichrome staining (Figure 6G upper panels). We also detected structural damage in kidney tissues from A-CKD mice (Figure 6G upper panel). On day 21, A-CKD mice from the vehicle group showed significantly larger fibrosis area than that seen on day 7, indicating the nephropathy was exacerbated by AdS injection in A-CKD mice between days 7 and 21 (Figure 6G-H lower panel and gray bar, respectively). However, on day 21, A-CKD mice from the HBP group showed significantly smaller fibrosis area than vehicle group mice (Figure 6G-H lower panel and black bar, respectively). These results overall suggest that HBP administration suppressed the progress of fibrosis in the kidney by blocking A-CKD progression and restoring hematopoiesis (Figure 6F-H).

Discussion

Unresolved inflammatory induction of hepcidin contributes to A-CKD, because excess hepcidin causes iron sequestration in iron-storage tissues and limits iron availability for hematopoiesis. In addition, disruption of hepcidin gene rescued the anemic phenotype in CKD mouse model.16 Therefore, it has been suggested that pharmacological reduction of excess hepcidin could offer therapeutic benefits to patients with A-CKD.17-19 This possibility is strengthened by the fact that hepcidin ablation relieves iron restriction and improves A-CKD in hepcidin knockout mice.20 Hence, several hepcidin antagonists that decrease the hepcidin-ferroportin interaction in a controlled manner are currently under investigation. Here, we present HBP as a hepcidin antagonist to treat A-CKD.

No change in plasma EPO levels in this experimental model is consistent with the observations that serum EPO levels in adenine-induced kidney disease model are similar to those in control10 and that serum EPO levels in patients with anemia and CKD are generally in the normal range or slightly increased.21 These results, taken together with data in Figure 5B-D, suggest that excess hepcidin is a principal cause of A-CKD by decreasing iron availability and that hepcidin-anemia axis is a new target for treatment in A-CKD. HBP administration partially restores hematopoiesis to block disease progression in A-CKD mice by inhibiting hepcidin activity to increase serum iron levels (Figure 5), thereby improving the renal microenvironment and suppressing the exacerbation of nephropathy.

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (HIF-PHI) stabilize HIF proteins to stimulate the expression of HIF-dependent genes, including the EPO gene.22 HIF-PHI that alter iron metabolism to favor hematopoiesis can antagonize anemia by stimulating EPO production.23-25 EPO induces the production of erythroferrone to limit the gene expression of hepcidin,26,27 thereby improving renal fibrosis.19,28,29 As a result, HIF-PHI ameliorate renal anemia in CKD animal models. Currently, HIF-PHI are clinically used to treat renal anemia.30,31 However, systemic prolyl hydroxylase inhibition could produce undesirable off-target effects, and patient safety concerns regarding their long-term use need to be carefully addressed in extended clinical studies and/or postmarketing investigations, because HIF proteins (HIF-1 and HIF-2) regulate numerous genes involved in multiple biological processes, including genes unrelated to erythropoiesis. These concerns include risk of oncogenesis, cardiovascular issues, angiogenesis increases that might accelerate the progression of diabetic retinopathy, metabolic changes that might exacerbate CKD, or renal cyst progression.32 Considering that HBP directly inhibits the hepcidin-ferroportin interaction, HBP is unlikely to cause the side effects mentioned above. We propose that HBP could provide a new therapeutic option to treat those diseases as well as A-CKD, because HBP specifically targets hepcidin to neutralize excess hepcidin activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elise Lamar for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by research funding from the Oyokyo Kidney Research Institute Research Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: S.T. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M.S. performed experiments; and T.S., C.O., and S.H. analyzed data and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shigeru Tsuboi, Department of Cancer Immunology and Cell Biology, Oyokyo Kidney Research Institute, 90 Kozawa Yamazaki, Hirosaki 036-8243, Japan; email: tsuboi@oyokyo.jp.

References

Author notes

Original data and protocols available are available to other investigators without unreasonable restrictions. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author, Shigeru Tsuboi (tsuboi@oyokyo.jp).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.