Key Points

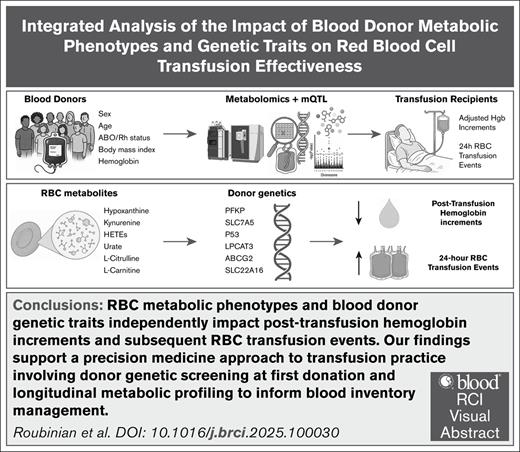

Previously reported blood donor metabolic phenotypes and genetic traits independently impact hemoglobin increments following RBC transfusion.

Donor genetic traits also impact downstream RBC transfusion events, highlighting the need for refined donor screening to optimize outcomes.

Visual Abstract

Recent large-scale population studies in humans and murine models of red blood cell (RBC) function identified associations between metabolic phenotypes or genetic traits linked to them and transfusion effectiveness. These metabolic phenotypes were identified in independent studies focusing on varied mechanistic aspects of the storage lesion. The lack of an integrated analysis raised the question as to whether these signatures were redundant measures of the same underlying processes or could be evaluated together to inform a precision medicine approach to clinical transfusion practice. To bridge this gap, we performed an integrated analysis in 5386 patients who received 6220 single-unit RBC transfusions, evaluating donor metabolic and genetic results from several studies on hemoglobin increments following RBC transfusion. Our results indicate that previously reported metabolic and genetic predictors of hemoglobin increments remain significant when evaluated concurrently. Our observational findings indicate that transfusing RBC units from donors with specific genetic traits are negatively associated not only with immediate effectiveness but also with increased downstream RBC transfusion events, further highlighting the need for refined donor screening practices. All this evidence supports the adoption of a precision medicine approach to transfusion practice, in which genetic screening of donors at first donation and longitudinal metabolic profiling could inform blood inventory management and allocation strategies, ensuring optimal outcomes for transfusion recipients.

Introduction

Every year, millions of patients worldwide rely on the transfusion of packed red blood cells (RBCs) as a critical, life-saving therapy. However, RBC storage under refrigerated blood bank conditions promotes the accumulation of a series of biochemical and morphological alterations collectively referred to as the storage lesion.1 Although clinical trials have mitigated concerns related to severe clinical sequelae of the “age of blood,” recent research has highlighted a disconnect between the chronological ex vivo storage age and the molecular or metabolic age of RBCs in a blood unit.2

Population studies in thousands of blood donors3 and hundreds of diversity outbred mice4 have shown that the onset, progression, and severity of the storage lesion vary from unit to unit as a function of donor and product processing factors. Demographic (eg, age, sex, race-ethnicity, and body mass index),5 genetic, and nongenetic factors, such as medication, dietary, or other exposures,6 contribute to the molecular differences of stored RBC units.

Within this framework, only a subset of markers of the metabolic storage lesion (eg, hypoxanthine3) seem to predict the propensity of stored RBCs to hemolyze in vitro or in vivo, as measured by changes in hemoglobin or bilirubin after transfusion.7,8 Alternatively, metabolites whose levels are donor-dependent but not affected by storage (eg, kynurenine) appear to better predict osmotic fragility in vitro and posttransfusion hemoglobin increments in vivo.9

Recently, we leveraged metabolite quantitative trait loci analyses in mice and humans, identifying genes associated with metabolic phenotypes to link key metabolic markers of altered energy3 and redox metabolism4 (especially purine10 or lipid peroxidation4 and related damage repair mechanisms via the Lands cycle11) with reduced hemoglobin increments after RBC transfusion in thousands of recipients in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study (REDS-III) RBC-Omics study.8

These results held several limitations. Notably, they were derived from independent studies focusing on separate metabolic aspects of the storage lesion, leaving open the question as to whether these metabolic phenotypes (and their associated genetic traits) were interrelated, independent, or mutually exclusive. In addition, most of these studies did not examine other clinically relevant sequelae, such as downstream transfusion requirements, following the receipt of RBC units from donors with specific metabolic/genetic traits. These limitations are addressed in the present analysis.

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data from the NHLBI REDS-III program through the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC).12,13 Approval for data collection was obtained from the institutional review board at each participating REDS-III center before submission as public use data to BioLINCC, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The database includes blood donor, product manufacturing, and transfused patient data collected at 12 academic hospitals in the United States from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2016. Donors who participated in the REDS-III RBC-Omics Study14 and had available genetic and RBC metabolite data were linked to RBC transfusion recipient outcomes using unique identifiers.

Study definitions

A transfusion episode was defined as any single RBC unit transfusion with pretransfusion and posttransfusion laboratory measures. Data regarding donor demographics, collection methods, and product manufacturing were extracted for each RBC unit. Metabolomic and genomic data on each RBC-Omics donor and their donated unit were linked to issued RBC units using donor identification numbers. Among transfusion recipients, we included adults who received single RBC units during 1 or more transfusion episodes and included demographics, storage duration, and hemoglobin levels measured by hospital clinical laboratories.

The primary outcome of hemoglobin increment was defined as the change in pretransfusion and posttransfusion hemoglobin levels following a single RBC unit transfusion. The secondary outcome was the number of RBC unit transfusions occurring within 48 hours of the index transfusion event.

Statistical methods

We assessed the univariable association of all a priori–selected donor, product, and recipient covariates with the primary outcome using linear regression. Any covariate that was associated (α = 0.2) with posttransfusion changes in hemoglobin was included in the multivariable model. We used generalized estimating equations to account for repeated transfusion events in a given recipient and control for other donor, product, and recipient covariates to assess associations between donor metabolite levels or alleles of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and hemoglobin increments in recipients after RBC transfusion. For donor SNPs associated with hemoglobin increments, we further examined the number of additional RBC units transfused within 48 hours of the index transfusion event, also using multivariable regression models. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata Version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results and discussion

We identified 5386 patients who received 6220 single-unit RBC transfusions for which blood donor, product, and recipient variables were linked to metabolic and genetic data (Table 1). Mean donor age was 53 years (standard deviation [SD], 15), 57.1% of RBC units were from male donors, and mean donor fingerstick hemoglobin level was 14.4 g/dL (SD, 1.2). A minority of RBC units were apheresis-derived (6.2%), the median RBC storage duration was 27 days (interquartile range, 15-36), and 26.5% of units were irradiated. Mean recipient age was 63 years (SD, 16), approximately half (53.6%) of recipients were male, and the mean pretransfusion hemoglobin level was 7.4 g/dL (SD, 0.9). The mean posttransfusion hemoglobin increment was 0.99 ± 0.82 g/dL, and additional RBC transfusions within 48 hours occurred after 45.6% (2836/6220) of index transfusion events. Among the 6220 linked RBC units, the prevalence of homozygous recessive alleles for the following SNPs that previous metabolite quantitative trait loci analyses had linked to heterogeneity in stored RBC units was as follows: hypoxanthine (14.5%), kynurenine (8.8%), hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE, combined isomers unresolved by ultrahigh throughput methods) (7.3%), and urate (2.0%). In donors with homozygous recessive alleles for hypoxanthine, 25.5% (248/973) of RBC units were irradiated, representing 4.0% (248/6220) of the total number of transfused units.

Blood donor, product, and transfusion recipient characteristics

| Characteristic . | No. of transfusion episodes (N = 6220 events) . |

|---|---|

| Donor demographic characteristics | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 3554 (57.1) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 53 (15) |

| Rh-positive status, n (%) | 5056 (81.3) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 2290 (36.8) |

| AB | 190 (3.0) |

| B | 887 (14.3) |

| O | 2853 (45.9) |

| Fingerstick hemoglobin level, mean (SD), g/dL | 14.4 (1.2) |

| Donor genetic characteristics∗ | |

| PFKP (hypoxanthine: RS2388595) | 973 (14.5) |

| SL7A5 (kynurenine: RS8052118) | 526 (8.8) |

| P53 (HETE: RS80649467) | 434 (7.3) |

| ABCG2 (urate: RS138409370) | 119 (2.0) |

| Blood product characteristics | |

| Apheresis-derived, n (%) | 387 (6.2) |

| Irradiated, n (%) | 1651 (26.5) |

| RBC storage duration, median (IQR), d | 27 (15-36) |

| Storage solution, n (%) | |

| AS-1 | 3049 (49.2) |

| AS-3 | 2701 (43.6) |

| Other | 470 (7.6) |

| Transfusion recipient characteristics | N = 5386 recipients |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 3332 (53.6) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63 (16) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 28 (24-33) |

| Rh-positive status, n (%) | 4776 (88.8) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 2089 (38.8) |

| AB | 300 (5.6) |

| B | 814 (15.1) |

| O | 2183 (40.5) |

| Pretransfusion hemoglobin level, mean (SD), g/dL | 7.4 (0.9) |

| Characteristic . | No. of transfusion episodes (N = 6220 events) . |

|---|---|

| Donor demographic characteristics | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 3554 (57.1) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 53 (15) |

| Rh-positive status, n (%) | 5056 (81.3) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 2290 (36.8) |

| AB | 190 (3.0) |

| B | 887 (14.3) |

| O | 2853 (45.9) |

| Fingerstick hemoglobin level, mean (SD), g/dL | 14.4 (1.2) |

| Donor genetic characteristics∗ | |

| PFKP (hypoxanthine: RS2388595) | 973 (14.5) |

| SL7A5 (kynurenine: RS8052118) | 526 (8.8) |

| P53 (HETE: RS80649467) | 434 (7.3) |

| ABCG2 (urate: RS138409370) | 119 (2.0) |

| Blood product characteristics | |

| Apheresis-derived, n (%) | 387 (6.2) |

| Irradiated, n (%) | 1651 (26.5) |

| RBC storage duration, median (IQR), d | 27 (15-36) |

| Storage solution, n (%) | |

| AS-1 | 3049 (49.2) |

| AS-3 | 2701 (43.6) |

| Other | 470 (7.6) |

| Transfusion recipient characteristics | N = 5386 recipients |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 3332 (53.6) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63 (16) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 28 (24-33) |

| Rh-positive status, n (%) | 4776 (88.8) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |

| A | 2089 (38.8) |

| AB | 300 (5.6) |

| B | 814 (15.1) |

| O | 2183 (40.5) |

| Pretransfusion hemoglobin level, mean (SD), g/dL | 7.4 (0.9) |

IQR, interquartile range. AS-1, additive solution 1; AS-3, additive solution 3.

Prevalence of homozygous recessive alleles in n (%).

Table 2 shows regression estimates from the multivariate model for hemoglobin increments, estimating the mean hemoglobin increment after transfusion for each level change (for categorical variables) or unit increase (for continuous variables). Analyzed together, hypoxanthine (–0.10 g/dL [95% confidence interval [CI], –0.8 to –0.02]), urate (–0.05 g/dL [95% CI, –0.12 to –0.01]), and low l-citrulline (0.05 g/dL [95% CI, 0.01-0.12]) levels were all significantly associated with reduced posttransfusion hemoglobin increments.

Regression estimates for hemoglobin increments after RBC transfusion (N = 6220)

| Characteristic . | Hemoglobin increment (95% CI), g/dL∗ . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Donor metabolite characteristics | ||

| Hypoxanthine | –0.10 (–0.18 to –0.02) | .01 |

| HETE | –0.03 (–0.07 to 0.01) | .13 |

| Urate | –0.05 (–0.12 to –0.01) | .04 |

| l-Citrulline | 0.05 (0.01-0.12) | .04 |

| Donor genetic characteristics | ||

| SLC7A5 (kynurenine: RS8052118) | –0.09 (–0.17 to 0.01) | .04 |

| P53 (HETE: RS80649467) | –0.13 (–0.22 to –0.04) | .01 |

| ABCG2 (urate: RS138409370) | –0.13 (–0.29 to –0.03) | .04 |

| Irradiation + PFKP (hypoxanthine: RS2388595) | –0.15 (–0.27 to –0.03) | .01 |

| Characteristic . | Hemoglobin increment (95% CI), g/dL∗ . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Donor metabolite characteristics | ||

| Hypoxanthine | –0.10 (–0.18 to –0.02) | .01 |

| HETE | –0.03 (–0.07 to 0.01) | .13 |

| Urate | –0.05 (–0.12 to –0.01) | .04 |

| l-Citrulline | 0.05 (0.01-0.12) | .04 |

| Donor genetic characteristics | ||

| SLC7A5 (kynurenine: RS8052118) | –0.09 (–0.17 to 0.01) | .04 |

| P53 (HETE: RS80649467) | –0.13 (–0.22 to –0.04) | .01 |

| ABCG2 (urate: RS138409370) | –0.13 (–0.29 to –0.03) | .04 |

| Irradiation + PFKP (hypoxanthine: RS2388595) | –0.15 (–0.27 to –0.03) | .01 |

Multivariable regression estimates estimating the mean hemoglobin increment after transfusion with 95% CIs accounting for the blood donor, product, and transfusion recipient covariates in Table 1.

Homozygous recessive alleles for key genes linked to kynurenine (–0.09 g/dl [95% CI, –0.17 to 0.01]), HETE (–0.13 g/dL [95% CI, –0.22 to –0.04]), and urate (–0.13 g/dL [95% CI, –0.29 to –0.03]) were significantly associated with reduced posttransfusion hemoglobin increments when analyzed together in multivariable analysis. In addition, homozygous recessive alleles for genes related to hypoxanthine were associated with reduced posttransfusion hemoglobin increments (–0.15 g/dL [95% CI, –0.27 to –0.03]) in gamma-irradiated RBC units. Compared with the reference alleles, homozygotes recessive alleles for the 3 donor SNPs (kynurenine, HETE, and urate) together were associated with reduced hemoglobin increments in transfused recipients (0.67 g/dL [95% CI, 0.48-0.87] vs 0.99 g/dL [95% CI, 0.96-1.03]) in our multivariable model.

Complementing the reduction in hemoglobin increments, the number of RBC units transfused within 48 hours for the recipients of RBC units from homozygous recessive donors compared with that for the recipients of RBC units from homozygous dominant donors was increased for SNPs related to kynurenine (0.42 [95% CI, 0.33-0.52] vs 0.29 [95% CI, 0.25-0.33] RBC units; P = .01) and urate (0.55 [95% CI, 0.36-0.74] vs 0.32 [95% CI, 0.28-0.35] RBC units; P = .02), but not for those related to hypoxanthine (0.34 [95% CI, 0.28-0.42] vs 0.29 [95% CI, 0.24-0.34] RBC units; P = .17) or HETE (0.30 [95% CI, 0.19-0.41] vs 0.32 [95% CI, 0.28-0.35] RBC units; P = .75). Translating the number of units to a discrete rate of transfusion, the recipients of RBC units from homozygous recessive compared with the recipients of RBC units from homozygous dominant donors had a higher rate of subsequent RBC transfusion events within 48 hours for HETE (41% [95% CI, 36-45] vs 31% [95% CI, 0.30-0.33]) and urate (39% [95% CI, 29-49] vs 33% [95% CI, 0.32-0.35]).

We have recently identified a series of RBC metabolic signatures4,9-11,15,16 (and genetic traits linked to them) that are associated with RBC survival in transfusion recipients. Here, we report that these identified signatures in transfused patients remain significant when analyzed together, suggesting that they are independent correlates of transfusion effectiveness. In addition, we demonstrate that combinations of heritable donor genetic variants may substantially reduce effectiveness of RBC transfusions (by 33%) in parallel to what we have shown with combinations in other donor and product factors (ie, donor sex and G6PD deficiency, irradiation, and prolonged storage duration).7,8 Future research identifying additional donor genetic and nongenetic characteristics could incrementally explain the observed variation in posttransfusion hemoglobin increments. We also report clinically relevant observations that the recipients of RBC units with these metabolic traits or from donors who carry genetic traits linked to these metabolic signatures are more likely to require additional RBC transfusions within 48 hours of the initial transfusion event. An increase in transfusion burden has previously been associated with worsened outcomes related to cardiopulmonary transfusion reactions and measures of quality of life.17,18

These observations support and expand upon previous findings and provide additional clinical rationale for the implementation of precision medicine approaches to transfusion medicine, involving donor genetic testing at first donation and longitudinal metabolic monitoring at consecutive donations as factors relevant to blood inventory management and prediction of transfusion effectiveness.19 Based on metabolic assessment at donation, certain blood units could be issued sooner rather than on a “first in, first out” basis or forgo irradiation when collected from donors who carry certain genetic traits that could predispose packed RBCs to accumulating characteristics of the metabolic storage lesion when irradiated and thus limiting transfusion effectiveness.

A limitation of the present study is the retrospective nature of our analysis, potentially subjecting the results to residual confounding despite multivariable adjustment. Future studies should prospectively validate these findings, further investigate mechanistic causality, and explore cost-effectiveness and feasibility of implementing donor genetic and metabolic assessments on a broader scale.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (grants R01HL126130, R01HL146442, R01HL149714, 75N2019D00033, and HHSN2682011).

Authorship

Contribution: N.H.R. had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the presented analyses; F.F., G.P.P., A.D., T.N., N.H.R., and C.P. were responsible for acquisition of data; C.P. and N.H.R. were responsible for the statistical analyses; A.D. supplied administrative, technical, or material support; all authors were responsible for study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and N.H.R. and A.D. wrote the first draft of the paper, which was critically reviewed and approved by all coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nareg H. Roubinian, Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, 5810 Owens Dr, Pleasanton, CA 94588; email: nareg.h.roubinian@kp.org.

References

Author notes

Details regarding access to the public use data set through BioLINCC (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/) and statistical code available on request from the corresponding author, Nareg H. Roubinian (nareg.h.roubinian@kp.org).