Key Points

Inclacumab, an anti–P-selectin Ab has a higher affinity for P-selectin than US Food and Drug Administration–approved crizanlizumab.

The efficacy of inclacumab in inhibiting cellular adhesion in the blood of patients with SCD was comparable with crizanlizumab.

Visual Abstract

Acute painful vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs) are the primary reason for emergency department visits by patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and contribute to significant morbidity in SCD. Crizanlizumab, a first-in-class humanized anti–P-selectin immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) monoclonal antibody (mAb), is approved in more than 40 countries for the prevention of VOEs in patients with SCD aged ≥16 years. Inclacumab, a fully human anti–P-selectin IgG4 mAb in clinical development, is believed to have a stronger affinity to P-selectin and greater maximal inhibition of cell-cell interactions than crizanlizumab. Using in vitro blinded experiments, we investigated whether crizanlizumab and inclacumab can be differentiated in terms of P-selectin binding affinity and inhibition of P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion in blood samples from healthy volunteers or patients with SCD. Surface plasmon resonance revealed that inclacumab had a higher P-selectin binding affinity than crizanlizumab; however, the inhibition of P-selectin–mediated cell adhesion was higher or comparable with crizanlizumab than inclacumab. Crizanlizumab and inclacumab were comparable in inhibiting leukocyte and erythrocyte adhesion to P-selection under vascular mimetic flow in microfluidic channels, platelet-leukocyte aggregation, and platelet aggregation in the blood of patients with SCD or control human blood. In summary, these results suggest that comparable or higher inhibition of cell adhesion with crizanlizumab vs inclacumab does not correlate with P-selectin binding affinity. Ultimately, clinical trials are required to evaluate how crizanlizumab vs inclacumab translates into treatment outcomes in patients with SCD.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive monogenic disorder that affects more than ∼8 million people worldwide and >100 000 African American people in the United States.1,2 SCD is caused by a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the β-globin gene, which leads to the generation of sickle hemoglobin (HbS).2 Intraerythrocytic polymerization of HbS promotes erythrocyte sickling, impaired rheology, hemolysis, and vaso-occlusion.2-5 Vaso-occlusion promotes acute systemic painful vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs), which are the primary reason for hospitalization of patients with SCD, and contributes to 90% of the health care cost associated with SCD.6,7 In vivo studies in SCD mice and in vitro studies with blood of patients with SCD have shown that P-selectin–mediated adhesion among leukocytes, platelets, erythrocytes, and vascular endothelium contributes to the development of vaso-occlusion, and therapeutically targeting P-selectin using function-blocking monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or inhibitors prevents the development of vaso-occlusion in SCD mice in vivo or patient blood in in vitro microfluidic channels.8-18

Crizanlizumab is a first-in-class humanized anti–P-selectin immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) mAb, which was recently approved in >40 countries to reduce/prevent VOE-related hospitalization in patients with SCD aged ≥16 years.19 However, the marketing authorization was recently withdrawn by regulatory agencies in some countries. Inclacumab is a fully human anti–P-selectin IgG4 mAb, which is currently being investigated in clinical trials for the prevention of VOE in patients with SCD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT04935879 and NCT04927247). Previous in vitro data suggest that inclacumab may have a stronger affinity to P-selectin and greater maximal inhibition of vaso-occlusive adhesion than crizanlizumab.4 In this study, we used 5 different in vitro assays in blinded experiments to compare the P-selectin binding affinity and ability to inhibit P-selectin–mediated cell-cell interactions by crizanlizumab vs inclacumab. Although inclacumab had a significantly higher P-selectin binding affinity than crizanlizumab, the efficacy of inclacumab in inhibiting P-selectin–dependent cell adhesion or aggregation in the blood of patients with SCD or control human blood was either less or comparable with that of crizanlizumab.

Methods

Biacore SPR assay

The affinity of both mAbs to their target, human P-selectin, was assessed with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy using Biacore technology (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL). Both mAbs were noncovalently captured on a protein A sensor chip, and solutions with different concentrations of recombinant human P-selectin were injected. From the obtained SPR sensorgrams, kinetic rate constants for association and dissociation and the equilibrium dissociation constant were determined.

Cell adhesion bioassay

Potency/biological activity of both mAbs was characterized using a cell-based adhesion assay measuring the inhibition of adhesion of P-selectin–expressing cells to recombinant human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1). V-bottom microtiter plates were coated with recombinant human PSGL-1, and then graded amounts of the respective mAb were added. The assay required cells that constitutively express human P-selectin on their surface. Recombinantly modified Raji cells that constitutively express human P-selectin on their surface are readily available from Eurofins DiscoverX. Therefore, these modified Raji cells were purchased and used in this study. Raji cells were fluorescently labeled and added to the plate. After incubation, the plate was centrifuged and nonadherent cells accumulated at the bottom of the V-shaped wells, from which they were measured using a fluorescence reader. The potency of the test sample was then quantified by comparing its ability to inhibit the adhesion of the P-selectin–expressing cells to PSGL-1 with that of a crizanlizumab reference standard. The samples and the standard were normalized based on protein content. Relative potency was calculated using a parallel line assay (using PLA 3.0; Stegmann Systems GmbH, Rodgau, Germany). The final result is expressed as the relative potency (in percent) of the sample compared with the reference standard.

Whole blood platelet aggregation assay

Citrated blood was collected from 12 healthy males with no significant medical conditions or medical history and no treatment with any antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs during the last 2 weeks before participation. Blood collection was done through the Novartis Basel tissue donor program (TRI0128) in accordance with the Swiss Human Research Act and approval of the responsible ethics committee. Platelet aggregation was evaluated using a Multiplate whole blood impedance aggregometry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd) in citrated blood. The analyzer continuously recorded platelet aggregation during the test. The increase of impedance by the attachment of platelets onto the Multiplate sensors was digitalized, transformed to arbitrary aggregation units, and plotted against time (minutes) on a 2-dimensional plot. The overall platelet aggregation assessed using this method was expressed as the area under the aggregation curve. Briefly, the aggregation experiments were conducted as follows: 300 μL of the Multiplate NaCl/CaCl2 diluent solution (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd) was placed in a Multiplate test cell maintained at 37°C; 300 μL of citrated blood previously incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with either crizanlizumab or inclacumab at 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 μg/mL or respective vehicles were added to the diluent solution. After 3 minutes, 20 μL of platelet agonist thrombin receptor-activating peptide type 6 (TRAP-6; a proteinase-activated receptor 1 agonist that mimics thrombin) at 1 mM, corresponding to 32 μM final total concentration, was added, and platelet aggregation was assessed for 15 minutes.

Platelet-leukocyte adhesion assay

Citrated whole blood was drawn from 10 healthy volunteers (Prevomed, Basel, Switzerland) after signing the informed consent (identical to the whole blood platelet aggregation assay). Only nonsmokers who were not on chronic transfusion therapy (no transfusion within the last 1 month) were included in the study. An informed written consent was obtained from all the participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All blood samples were used within 45 minutes of collection. In separate studies held at the University of Pittsburgh, citrated whole blood samples were drawn from patients with SCD (8 Hb sickle cell anemia, 1 Hb sickle β0-thalassemia, and 1 HbSC) at a steady state based on an institutional review board (IRB) protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh. SCD or control human blood samples were preincubated with different doses of crizanlizumab or inclacumab and then incubated with a vehicle or 32 μM TRAP-6 to stimulate platelet-leukocyte aggregate (PLA) formation. Afterward, the blood was fixed and stained with fluorescent Abs, and flow cytometry was conducted to estimate the PLA, as described in the supplemental Methods and supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Microfluidic flow adhesion bioassay

Informed consent protocols were performed following the IRB protocol approved by Wayne State University IRB. Blood samples were collected from 10 patients with SCD (Hb sickle cell anemia). Blood was drawn by venipuncture into anticoagulated vacutainer tubes containing sodium citrate and stored for up to 48 hours at 4°C before assay. Flow adhesion experiments were conducted using a commercially available microfluidic flow adhesion system, the BioFlux 1000Z (Fluxion, San Francisco, CA). Microfluidic channels were coated by perfusing them with a solution of VCAM-1 or P-selectin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a flow rate of 2 dynes/cm2 for 5 minutes, followed by an incubation step at room temperature for 1 hour. The channels were then washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; with calcium and magnesium) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin at a flow rate of 5 dyne/cm2 for 5 minutes to remove any unbound VCAM-1 or P-selectin. White blood cells were isolated from the whole blood samples using Histopaque-1077 and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice and normalized to 5 × 106 cells per mL in HBSS buffer. Both white blood cell suspensions and whole blood samples were incubated with increasing concentrations of crizanlizumab or inclacumab for 5 minutes, respectively, before perfusion through the multiple microfluidic well plate. Whole blood was appropriately diluted (1:1) in HBSS buffer. The treated/diluted blood or treated white blood suspension (5 × 106 cells per mL) was perfused through the microfluidic channels under physiological flow conditions, specifically at a rate of 1 dyne/cm2 and a frequency of 1.67 Hz for 10 minutes for whole blood and for 6 minutes for white blood cell suspension. High-resolution charge-coupled device camera images were captured, and an independent observer manually counted the adherent cells in individual photomicrographs. To measure adhesion levels, 3 flow adhesion indices were established: flow adhesion of isolated white blood cells on P-selectin (FA-WBC-Psel) for quantifying isolated white blood cells adhering to P-selectin, flow adhesion of whole blood to P-selectin (FA-WB-Psel) for whole blood cells adhering to P-selectin, and flow adhesion of whole blood to VCAM (FA-WB-VCAM) for whole blood cells adhering to VCAM-1. Each index was calculated by counting the adherent cells within a standardized viewing area, expressed as the number of cells per square millimeter.

Statistical analysis

Data were shown as mean ± standard deviation. Means were compared using the unpaired Student t test or a repeated measures 1-way analysis of variance test and Šídák multiple comparison test. P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

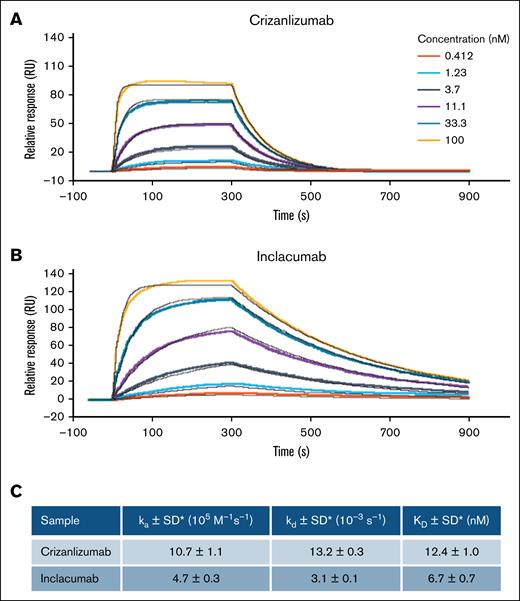

P-selectin binding affinity was higher for inclacumab than crizanlizumab

SPR was used to assess the real-time, label-free detection of interactions of inclacumab or crizanlizumab with P-selectin. Both mAbs recognized P-selectin with binding affinities of the same order of magnitude (nanomolar range). However, there was a clear trend toward higher P-selectin binding affinity of inclacumab than crizanlizumab (Figure 1; equilibrium dissociation constant [mean ± standard deviation], 6.7 ± 0.7 nM vs 12.4 ± 1.0 nM; P < .05). As shown in Figure 1, the state of equilibrium was reached more quickly and ended more quickly with crizanlizumab than inclacumab. Given that additional factors influence target binding in vivo, such as mAb subclass (IgG2 [crizanlizumab] vs IgG4 [inclacumab]), it was not considered meaningful to further directly compare relative responses of the 2 mAbs.

P-selectin binding affinity was higher for inclacumab than for crizanlizumab. P-selectin binding affinity of crizanlizumab (A) and inclacumab estimated using Biacore SPR assay (B). (C) Average kinetic parameters calculated from 4 measurements (2 independent experiments) are shown. ka, association constant; kd, dissociation constant; KD, equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = kd/ka); SD, standard deviation. ∗P ≤ .05.

P-selectin binding affinity was higher for inclacumab than for crizanlizumab. P-selectin binding affinity of crizanlizumab (A) and inclacumab estimated using Biacore SPR assay (B). (C) Average kinetic parameters calculated from 4 measurements (2 independent experiments) are shown. ka, association constant; kd, dissociation constant; KD, equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = kd/ka); SD, standard deviation. ∗P ≤ .05.

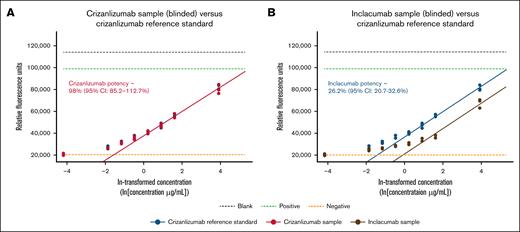

Crizanlizumab is a more potent inhibitor of P-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction than inclacumab

Potency of both mAbs was characterized using a cell-based adhesion assay measuring the inhibition of the adhesion of P-selectin–expressing Raji cells to recombinant human PSGL-1. In this function-related bioassay, crizanlizumab demonstrated significantly stronger inhibition of the adhesion of the P-selectin–expressing cells to PSGL-1 than inclacumab. Relative potency results were obtained against a crizanlizumab reference standard for both mAbs. Refer to “Methods” for details. Potency for crizanlizumab was 98% (95% confidence interval, 85.2-112.7) as expected, whereas potency for inclacumab was significantly lower, 26.2% (95% confidence interval, 20.7-32.6). Respective dose response curves, including a parallel line analysis, are shown in Figure 2.

Inhibition of P-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction by inclacumab vs crizanlizumab. Cell-based adhesion assays were conducted to assess the inhibition of adhesion of P-selectin–expressing cells to PSGL-1 by different concentrations of inclacumab or crizanlizumab. (A-B) Next, dose response curves were created, and P-selectin inhibition potencies of 2 mAbs were determined by parallel line analyses, as described in “Methods.” Measured potencies were 98.0% for crizanlizumab (95% CI, 85.2-112.7) in panel A and 26.2% for inclacumab (95% CI, 20.7-32.6) in panel B, determined relative to a crizanlizumab reference standard, including the determined CI. Refer to “Methods” for details on the experimental analysis. CI, confidence interval; ln, natural logarithm.

Inhibition of P-selectin–PSGL-1 interaction by inclacumab vs crizanlizumab. Cell-based adhesion assays were conducted to assess the inhibition of adhesion of P-selectin–expressing cells to PSGL-1 by different concentrations of inclacumab or crizanlizumab. (A-B) Next, dose response curves were created, and P-selectin inhibition potencies of 2 mAbs were determined by parallel line analyses, as described in “Methods.” Measured potencies were 98.0% for crizanlizumab (95% CI, 85.2-112.7) in panel A and 26.2% for inclacumab (95% CI, 20.7-32.6) in panel B, determined relative to a crizanlizumab reference standard, including the determined CI. Refer to “Methods” for details on the experimental analysis. CI, confidence interval; ln, natural logarithm.

Crizanlizumab is a more potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation than inclacumab

PLA contributes to the development of vaso-occlusion in SCD.8,20 In whole blood, P-selectin–mediated leukocyte-platelet interactions also contribute to the formation of platelet aggregates.8,20,21 Therefore, we also compared the inhibitory effect of both Abs on TRAP-6–induced platelet aggregation in whole human blood using platelet aggregometry. The whole blood assay was used to assess the efficacy of 2 mAbs in inhibiting platelet aggregation in TRAP-6– or PBS-treated whole blood from healthy human volunteers. As shown in Figure 3, inhibition of TRAP-6–dependent platelet aggregation (relative to PBS treatment) was comparable for crizanlizumab and inclacumab (maximum inhibition of −22% and −26% for inclacumab and crizanlizumab, respectively); however, the percent inhibition in platelet aggregation was significantly higher for crizanlizumab than inclacumab at higher concentrations (>1 μg/mL), and the concentration required to achieve 50% of the maximum inhibitory effect (IC50) was twofold lower for crizanlizumab than inclacumab (5.11 vs 10.36 μg/mL). Indeed, both Abs led to a partial inhibition of TRAP-6–induced platelet aggregation in whole blood (Figure 3), suggestive of a minor contribution of P-selectin–dependent leukocyte-platelet interaction to whole blood platelet aggregation. As expected, tirofiban (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor) led to a >90% inhibition (maximum percent inhibition, −93%; IC50, 24.4 ng/mL).

Inhibition of TRAP-6-induced platelet aggregation with crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in healthy control human whole blood. Venous blood drawn from 12 healthy control human subjects and used in a whole blood platelet aggregation assay, as described in “Methods.” One-way analysis of variance vs vehicle control: ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001. Error bars show the standard deviation (SD).

Inhibition of TRAP-6-induced platelet aggregation with crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in healthy control human whole blood. Venous blood drawn from 12 healthy control human subjects and used in a whole blood platelet aggregation assay, as described in “Methods.” One-way analysis of variance vs vehicle control: ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001. Error bars show the standard deviation (SD).

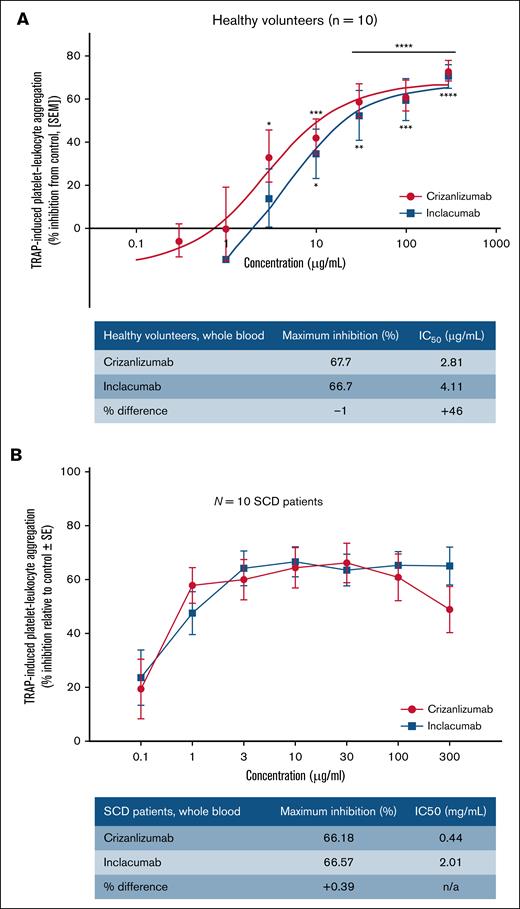

Crizanlizumab is a more potent inhibitor of PLA than inclacumab

Flow cytometry analysis was used to compare the efficacy of 2 mAbs in inhibiting PLA in whole blood of healthy control volunteers or patients with SCD incubated with PBS or 32 μM TRAP-6. Clinical characteristics of these patients with SCD are presented in Table 1. Refer to Methods for details. The percent inhibition (relative to PBS treatment) of PLA in healthy human whole blood was comparable for crizanlizumab and inclacumab (maximum inhibition, 67.7% vs 66.7%; Figure 4A), with a clear trend toward higher inhibition by crizanlizumab than inclacumab at a lower concentration (<10 μg/mL). IC50 was higher with inclacumab than crizanlizumab (4.11 vs 2.81 μg/mL). In whole blood from patients with SCD, inhibition of PLA was again comparable for crizanlizumab and inclacumab (maximum inhibition, 66.18% vs 66.57%; Figure 4B). IC50 was higher with inclacumab than crizanlizumab (2.01 vs 0.44 μg/mL). As shown in Figure 4, the IC50 for crizanlizumab (0.44 vs 2.81) and inclacumab (2.01 vs 4.11) were lower in SCD than in control human blood. The inflammatory milieu in SCD is known to promote P-selectin exposure on the platelet surface, leading to elevated levels of PLAs in SCD than in control human blood.3,5,8 Treatment with TRAP could further upregulate P-selectin expression, leading to even higher PLA formation in TRAP-treated SCD than in TRAP-treated control human blood. These differences may contribute to a lower threshold (IC50) for inhibition of PLA by both Abs in SCD than in control human blood. Indeed, the inhibition curve plateaued at 10-fold lower concentration for both Abs in TRAP-treated SCD than in control human blood (Figure 4).

Clinical characterization of patients with SCD used in the PLA assay

| Female/male | 6/4 |

| Age (y) | 41.40 (41; 30-61) |

| Red blood cells (×103/μL) | 2.82 (2.55; 1.92-4.8) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.52 (9.65; 6.8-13.7) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 27.37 (28.55; 19.6-37.7) |

| White blood cells (×103/μL) | 8.69 (7.35; 3.2-13.2) |

| % neutrophils | 56.38 (58.3; 39-72) |

| % lymphocytes | 26.09 (21.75; 8-49) |

| % monocytes | 8.9 (9.45; 1.4-14) |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 360.2 (308.5; 113-860) |

| % HbF | 13.51 (9.75; 1.5-35.4) |

| SCD genotype | |

| SS | 8 |

| S/β0 | 1 |

| SC | 1 |

| Hydroxyurea (yes/no) | 6/4 |

| Female/male | 6/4 |

| Age (y) | 41.40 (41; 30-61) |

| Red blood cells (×103/μL) | 2.82 (2.55; 1.92-4.8) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.52 (9.65; 6.8-13.7) |

| Hematocrit (%) | 27.37 (28.55; 19.6-37.7) |

| White blood cells (×103/μL) | 8.69 (7.35; 3.2-13.2) |

| % neutrophils | 56.38 (58.3; 39-72) |

| % lymphocytes | 26.09 (21.75; 8-49) |

| % monocytes | 8.9 (9.45; 1.4-14) |

| Platelets (×103/μL) | 360.2 (308.5; 113-860) |

| % HbF | 13.51 (9.75; 1.5-35.4) |

| SCD genotype | |

| SS | 8 |

| S/β0 | 1 |

| SC | 1 |

| Hydroxyurea (yes/no) | 6/4 |

Data show mean (median; range) except for the sex and hydroxyurea status.

HbF, fetal hemoglobin; S/β0, sickle β0-thalassemia; SC, hemoglobin SC disease; SS, sickle cell anemia.

Inhibition of PLA by crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in control or SCD human blood. Flow cytometry was used to assess the inhibition of PLA by different concentrations of crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in TRAP-6–treated blood of healthy control humans (N = 10) (A) and patients with SCD (N = 10) (B). Data represent the mean (±standard error) percent inhibition of PLA at each concentration by 2 mAbs and were compared using the paired Student t test. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001. SEM, standard error of the mean.

Inhibition of PLA by crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in control or SCD human blood. Flow cytometry was used to assess the inhibition of PLA by different concentrations of crizanlizumab vs inclacumab in TRAP-6–treated blood of healthy control humans (N = 10) (A) and patients with SCD (N = 10) (B). Data represent the mean (±standard error) percent inhibition of PLA at each concentration by 2 mAbs and were compared using the paired Student t test. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001. SEM, standard error of the mean.

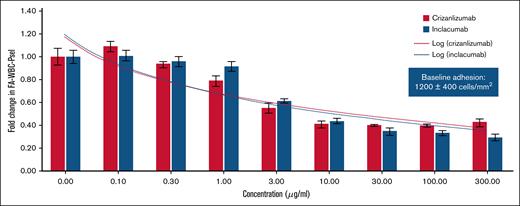

Two mAbs were equally potent in inhibiting leukocyte adhesion under shear flow

Next, we assessed the efficacy of crizanlizumab and inclacumab in inhibiting leukocyte (isolated cell suspension or in whole blood) adhesion to P-selectin–coated substrate under vascular mimetic shear flow. Venous blood samples were collected from patients with SCD (clinical characteristics of these patients presented in Table 2). Whole blood or leukocyte suspension was perfused through microfluidic channels coated with P-selectin or VCAM-1 at a physiological shear stress as described in Methods. To quantify the extent of adhesion, 3 flow adhesion indices were established: FA-WBC-Psel for quantifying isolated white blood cells adhering to P-selectin substrate, FA-WB-Psel for whole blood cells adhering to P-selectin substrate, and FA-WB-VCAM for whole blood cells adhering to VCAM-1 substrate. Each index was calculated by counting the adherent cells within a standardized viewing area, expressed as cells/mm2. For crizanlizumab and inclacumab, dose-dependent inhibition of FA-WBC-Psel (Figure 5) and FA-WB-Psel (supplemental Figure 1) was observed, with no significant difference between the 2 mAbs. In relation to the clinically approved crizanlizumab dose (5.0 mg/kg), a concentration of 100 μg/mL corresponds to the maximum plasma concentration and a concentration of ∼10 to 15 μg/mL corresponds to the trough plasma concentration. An mAb concentration of 10 μg/mL resulted in statistically significant inhibition of flow adhesion indices by ∼60%, and further increasing the mAb concentration did not result in further reduction beyond this threshold (Figure 5). In addition to leukocytes, sickle erythrocytes are also known to adhere to P-selectin and contribute to the development of vaso-occlusion.7 Indeed, both leukocytes and erythrocytes were found to adhere to P-selectin substrate in microfluidic channels perfused with untreated blood of patients with SCD (supplemental Figure 1B). In contrast, fewer adherent leukocytes and erythrocytes adhered to P-selectin substrate in microfluidic channels perfused with either 100 μg/mL crizanlizumab- (supplemental Figure 1C) or inclacumab-treated blood of patients with SCD (supplemental Figure 1D). Importantly, erythrocytes accounted for an average of 30% of all adhered blood cells (range, 14%-45%) across all doses of crizanlizumab and inclacumab, suggestive of no difference between the 2 mAbs in inhibiting erythrocyte adhesion to immobilized P-selectin under flow. In contrast to P-selectin–coated microfluidic channels, there was no effect of 2 mAbs on FA-WB-VCAM (adhesion to VCAM-1), suggestive of the specificity of these mAbs in blocking P-selectin (supplemental Figure 2).

Clinical characterization of patients with SCD used in a microfluidic flow bioassay

| Age (y) . | Sex . | Race . | SCD genotype . | HbA2 (%) . | HbS (%) . | HbF (%) . | Reticulocyte (%) . | Hydroxyurea . | Voxelotor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | M | Black/AA | SS | 3 | 84.7 | 12.3 | 12.3 | Y | N |

| 14 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.9 | 90.1 | 7.0 | 5.8 | Y | Y |

| 16 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.3 | 71.3 | 17.9 | 12.3 | Y | N |

| 16 | M | Black/AA | SS | 2.6 | 60.3 | 16.0 | 13.5 | Y | Y |

| 7 | F | Middle Eastern | SS | 2.4 | 69.3 | 28.3 | 7.6 | Y | N |

| 14 | M | Black/AA | SS | 2.9 | 76.4 | 20.7 | 9.4 | N | N |

| 7 | M | Black/AA | SS | NM | NM | NM | 18.2 | N | N |

| 15 | M | Black/AA | SS | 3.2 | 84.8 | 12.0 | 10.7 | Y | N |

| 5 | F | Black/AA | SS | 3.3 | 83.7 | 13.0 | 13.8 | Y | N |

| 15 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.8 | 85.2 | 6.4 | 9.3 | Y | Y |

| Age (y) . | Sex . | Race . | SCD genotype . | HbA2 (%) . | HbS (%) . | HbF (%) . | Reticulocyte (%) . | Hydroxyurea . | Voxelotor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | M | Black/AA | SS | 3 | 84.7 | 12.3 | 12.3 | Y | N |

| 14 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.9 | 90.1 | 7.0 | 5.8 | Y | Y |

| 16 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.3 | 71.3 | 17.9 | 12.3 | Y | N |

| 16 | M | Black/AA | SS | 2.6 | 60.3 | 16.0 | 13.5 | Y | Y |

| 7 | F | Middle Eastern | SS | 2.4 | 69.3 | 28.3 | 7.6 | Y | N |

| 14 | M | Black/AA | SS | 2.9 | 76.4 | 20.7 | 9.4 | N | N |

| 7 | M | Black/AA | SS | NM | NM | NM | 18.2 | N | N |

| 15 | M | Black/AA | SS | 3.2 | 84.8 | 12.0 | 10.7 | Y | N |

| 5 | F | Black/AA | SS | 3.3 | 83.7 | 13.0 | 13.8 | Y | N |

| 15 | F | Black/AA | SS | 2.8 | 85.2 | 6.4 | 9.3 | Y | Y |

AA, African American; F, female; HbA2, hemoglobin A2; M, male; NM, not measured.

Inhibition of leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin substrate under vascular mimetic flow. Leukocytes isolated from the venous blood of patients with SCD (n = 10). Cell suspension with or without addition of crizanlizumab or inclacumab (at different concentrations) perfused through microfluidic flow channels coated with recombinant human P-selectin. FA-WBC-Psel was estimated as described in Methods. Relative fold change in FA-WBC-Psel from baseline was calculated from the mean (±SD) at each concentration tested among all 10 patients. Baseline adhesion (shown in box) defined as baseline leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin substrate across the 10 patients. Shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2 with a pulsatility of 1.67 Hz. In relation to the clinically approved crizanlizumab dose (5.0 mg/kg), a concentration of 100 μg/mL corresponds to Cmax (maximum plasma concentration) and ∼10 to 15 μg/mL corresponds to Ctrough (trough plasma concentration).

Inhibition of leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin substrate under vascular mimetic flow. Leukocytes isolated from the venous blood of patients with SCD (n = 10). Cell suspension with or without addition of crizanlizumab or inclacumab (at different concentrations) perfused through microfluidic flow channels coated with recombinant human P-selectin. FA-WBC-Psel was estimated as described in Methods. Relative fold change in FA-WBC-Psel from baseline was calculated from the mean (±SD) at each concentration tested among all 10 patients. Baseline adhesion (shown in box) defined as baseline leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin substrate across the 10 patients. Shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2 with a pulsatility of 1.67 Hz. In relation to the clinically approved crizanlizumab dose (5.0 mg/kg), a concentration of 100 μg/mL corresponds to Cmax (maximum plasma concentration) and ∼10 to 15 μg/mL corresponds to Ctrough (trough plasma concentration).

Discussion

Painful VOEs are the predominant reason for hospitalization of patients with SCD and substantially contribute to the health care cost for the management of patients with SCD in the United States.6 P-selectin–dependent adhesion among leukocytes, platelets, erythrocytes, and vascular endothelium contributes to the development of vaso-occlusion in SCD.3 Recently, a humanized anti–P-selectin function-blocking mAb, crizanlizumab, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the first targeted therapy for the prevention of VOE-related hospitalization among patients with SCD.19 In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 clinical trial, a monthly intravenous dose of 5 mg/kg crizanlizumab led to ∼50% reduction in frequency of VOE among patients with SCD,19 suggesting that the therapeutic efficacy may be further improved by developing mAbs with higher P-selectin affinity than crizanlizumab.

Inclacumab is the recently developed human anti–P-selectin function-blocking mAb, which is currently being tested in clinical trials to determine whether it has improved therapeutic efficacy in reducing VOE incidence in patients with SCD. Here, we show that inclacumab is more potent than crizanlizumab in binding to human P-selectin. However, inclacumab was not more potent than crizanlizumab in inhibiting adhesion of P-selectin–expressing cells to PSGL-1. Although inclacumab was comparable with crizanlizumab in preventing platelet aggregation in TRAP-6–treated control human blood, crizanlizumab seemed to be more potent than inclacumab at higher concentrations. Both inclacumab and crizanlizumab were equally potent in inhibiting PLA in TRAP-6–treated healthy control human or blood of patients with SCD. Finally, microfluidic adhesion assays revealed both mAbs to be equally potent in inhibiting (∼60%) leukocyte and erythrocyte adhesion to immobilized P-selectin in the flowing blood of patients with SCD. Several factors may contribute to this partial inhibition, including concentration of the mAbs, binding affinity of the mAbs, and the surface density of P-selectin in the in vitro microfluidic channel.22,23 The goal of this study was to compare the inhibition potency of inclacumab with the clinically approved dose of crizanlizumab (5 mg/kg); therefore, the mAb concentrations used in microfluidic adhesion assays were related to the range of plasma concentration observed for the FDA-approved dose. Concentrations higher than the FDA-approved dose might lead to stronger inhibition; however, whether these doses can completely abolish P-selectin–dependent blood cell adhesion in the blood of patients with SCD and the clinical relevance of such doses would require further investigation in future studies. In addition, the disease severity is known to be heterogeneous among patients with SCD; however, the cohort used in the current study was not large enough to model this heterogeneity, which would require a larger cohort of patients with SCD in future studies. Altogether, our in vitro findings suggest that inclacumab is not more potent than crizanlizumab in preventing P-selectin–dependent cell adhesion in SCD. These findings may also inform the future development of antiadhesion therapeutic mAbs by suggesting that improving the P-selectin binding affinity of humanized mAbs may not necessarily translate into a further increase in P-selectin blocking efficiency beyond a certain threshold. Alternatively, P-selectin inhibition may also affect endothelium activation and other inflammatory biomarkers in patients with SCD in vivo, which can contribute to differences in clinical efficacy of 2 mAbs in ongoing clinical trials. Crizanlizumab therapy is a lifelong treatment, which requires a monthly transfusion and accounts for an annual cost of ∼$100 000 per patient in the United States.24,25 In addition, the lack of clinical benefit in the recent phase 3 clinical trial has led to the discontinuation of crizanlizumab in the European Union, highlighting the urgent need for better therapies to treat VOE. Regardless of these in vitro findings that suggest inclacumab to be similar to crizanlizumab in inhibiting blood cell adhesion, the higher P-selectin binding affinity of inclacumab than crizanlizumab may still lead to higher efficacy of inclacumab than crizanlizumab in preventing VOE in vivo in humans, which can only be confirmed after the completion of ongoing clinical trials to test inclacumab for the prevention of VOE in patients with SCD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT04935879 and NCT04927247).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Enrico Novelli of the University of Pittsburgh, who provided blood samples of patients with sickle cell disease for the platelet-leukocyte aggregate assay. The authors thank Carla Schmidt from Novartis for running the cell-based assay and Jessica Boll and Aurelie Castan from Novartis for running the Biacore experiments. Crizanlizumab is developed by Novartis.

These experiments were funded by Novartis. P.S. was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grants R01HL128297, R01HL141080, and R01HL166345); the American Heart Association (grants 18TPA34170588 and 23TPA1074022); funds from the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania and Vitalant; and the Versiti Blood Research Institute Foundation. T.B. was supported by the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Postdoctoral Scholar Award, the ASH Research Restart Award, the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania, and Vitalant. T.W.K. was supported by the American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (AHA828786) and Judith Graham Pool fellowship from the National Bleeding Disorders Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: P.S., T.W.K., T.B., T.P.-S., and R.K.D. conducted the platelet-leukocyte aggregate (PLA) assay using blood samples from patients with sickle cell disease; T.R.-S., D.G., J.H., and C.B.-M. conducted the PLA assay using blood samples from healthy volunteers; F.K. and M.V. conducted the Biacore surface plasmon resonance assay; F.K. conducted the cell adhesion bioassay; A.M.D. and R.B. gave input to the manuscript; D.L., B.C.d.B., and B.G. conducted the whole blood assay using blood samples from healthy volunteers; X.G. and P.C.H. conducted the microfluidic flow adhesion bioassays, in collaboration with A.B. and M.D.; and P.S. and T.R.-S. wrote the manuscript after a discussion with all the coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.S. reports research funding from Bayer, CSL Behring Inc, Novartis, and IHP Therapeutics; and membership on a board of directors/advisory committees for Novartis and IHP Therapeutics. T.R.-S., D.L., and M.V. report current employment and are current holders of stock options in a publicly traded company with Novartis Pharma AG. D.G. reports current employment with Novartis Pharma AG and is a current holder of Novartis and Alcon stock options. J.H. reports current employment with Novartis Pharma AG and is a current holder of Novartis stock options. B.C.d.B. and A.B. report current employment with Novartis Pharma AG. C.B.-M. reports current employment with Light Chain Bioscience–Novimmune SA and ended employment in the past 24 months with Novartis Pharma AG. B.G. reports current employment and is a current holder of individual stocks and stock options in a publicly traded company with Novartis Pharma AG. F.K. reports current employment, being a current equity holder in a publicly traded company, and patents and royalties (WO2021087050A1) with Novartis Pharma AG. X.G. reports current employment with Functional Fluidics. M.D. reports current employment with Novartis. A.M.D. and R.B. report current employment with Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation and are holders of Novartis stock options. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Prithu Sundd, Thrombosis and Hemostasis Program, Versiti Blood Research Institute and Blood Center of Wisconsin, 8733 W Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; email: psundd@versiti.org; and Tina Rubic-Schneider, Translational Medicine & Preclinical Safety, Novartis Pharma AG, Fabrikstrasse 2, Novartis Campus, CH-4056 Basel, Switzerland; email: tina.rubic@novartis.com.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding authors, Prithu Sundd (psundd@versiti.org) or Tina Rubic-Schneider (tina.rubic@novartis.com).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.