Key Points

ECV measured by CMR is stable and reproducible over 2 years, supporting its role as a reliable imaging biomarker in clinical studies.

ECV was independently associated with hemoglobin, DD, NT-proBNP, left atrial volume, and peak pulmonary artery velocity, at all points.

Visual Abstract

Diffuse myocardial fibrosis is a key feature of the cardiomyopathy of sickle cell anemia (SCA) that is linked to diastolic dysfunction (DD). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR)–derived extracellular volume fraction (ECV) is a quantitative biomarker of myocardial fibrosis that is elevated in SCA. The stability of ECV in SCA and its clinical associations over time are unknown. To measure longitudinal changes in ECV, without specific intervention, and identify correlates of ECV change in patients with SCA, we conducted a prospective, 2-year study involving annual CMR, echocardiography, and laboratory assessments in 24 patients with SCA (mean age, 21.4 ± 10 years). ECV was calculated using T1 mapping before and after gadolinium, and extracellular matrix and cellular volumes were calculated to account for relative changes. Diastolic function was classified by echocardiography. Longitudinal associations were assessed using linear mixed-effects models. ECV was abnormally increased at baseline and remained stable over time (mean change, −1.1% ± 2.7% per year). Intrapatient ECV variability was low (mean, 2.4%), with no differences by age or sex. ECV correlated with DD at all time points (P = .01). Changes in ECV were more closely associated with changes in extracellular matrix volume (P = .01) than with myocardial cell volume. In a longitudinal multivariable analysis, ECV was independently associated with DD, hemoglobin, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), left atrial volume, and peak pulmonary artery velocity. In summary, ECV is a stable and reliable metric of myocardial extracellular matrix expansion in SCA. Its strong associations with DD, NT-proBNP, and other biomarkers of cardiac stress support its use as an imaging biomarker for antifibrotic therapies in SCA. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT02410811.

Introduction

Adults with sickle cell anemia (SCA) are at high risk for premature cardiac mortality. Despite this, the effects of SCA on the heart have not been studied well. Recently, we, and others, have shown that there is a unique cardiomyopathy of SCA characterized by diastolic dysfunction, often with features of restrictive physiology, that is superimposed on an anemia-related high-output state.1,2 Additional characteristics of this cardiomyopathy include 4-chamber dilation, normal or increased systolic function, and susceptibility to dysrhythmia. Myocardial fibrosis has emerged as a key, underlying feature of the SCA-related cardiomyopathy, which is linked to diastolic dysfunction. Macroscopic focal fibrosis (scarring), similar to that seen after coronary artery occlusion, is uncommon in patients with SCA; however, diffuse, interstitial myocardial fibrosis is consistently found both in animal and human studies.1,3-5

Myocardial fibrosis is a maladaptive process characterized by excessive collagen deposition in the extracellular matrix, leading to increased myocardial stiffness and impaired relaxation.6-8 In many cardiovascular diseases, myocardial fibrosis is strongly associated with adverse outcomes, including dysrhythmias, heart failure, and death.9,10 In SCA, diffuse myocardial fibrosis correlates with diastolic dysfunction, a known independent predictor of mortality, and exercise impairment, together supporting the clinical relevance of this pathogenic mechanism in SCA.5,11,12

Diffuse myocardial fibrosis can be detected and quantified noninvasively by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) using the extracellular volume fraction (ECV) metric.13 ECV quantifies the fraction (volume percent) of the myocardial interstitial space, which consists primarily of the extracellular matrix (predominantly collagen) and vascular space (primarily capillaries). ECV measurements are robust, reproducible, and strongly correlate with histologic collagen fraction,14,15 especially in the absence of edema or amyloidosis. Importantly, ECV has been validated as a predictor of adverse clinical outcomes including cardiac decompensation, hospitalization, and death in several disease states.16

ECV is nearly universally increased in SCA. In our cohort, ECV was abnormally increased in all patients (n = 25) at baseline, even in children as young as 6 years of age.5 Subsequent studies have also shown universally increased ECV.17,18 In SCA, an increased ECV is associated with diastolic dysfunction, the severity of anemia, and increased N-termina pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), a myocardial stress marker associated with early mortality.5,19 Thus, as a noninvasive, quantitative metric, ECV is a compelling disease biomarker and a potential surrogate endpoint in clinical trials assessing antifibrotic therapies in SCA.20,21

Despite its validation and clinical utility in other cardiomyopathies, the suitability of longitudinal ECV measurements in SCA for monitoring disease progression or therapeutic response has, to our knowledge, not been established. The few published studies of ECV in SCA have been cross-sectional, offering limited insight into intrapatient temporal variability and other determinants of ECV change. Therefore, we conducted a 2-year, prospective, longitudinal study to assess the stability of ECV measurements over time in children and adults with SCA. Importantly, no antifibrotic therapy based on the degree of myocardial fibrosis was initiated during the study period. We also studied clinical, laboratory, and imaging correlates of temporal changes in ECV.

Methods

Participants and study design

This is a prospective study of CMR to characterize SCA-related cardiomyopathy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02410811). Details of the study design and enrollment criteria have been previously described.5 Briefly, key inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of hemoglobin SS (HbSS) or HbSβ0 thalassemia (together considered as SCA for this study), age of ≥6 years, and ability to undergo CMR and echocardiography without sedation. Key exclusion criteria were chronic transfusion therapy, known congenital heart disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate of <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and any contraindication to CMR.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants or legal guardians, and assent was also obtained from children aged ≥12 years.

Clinical and laboratory data

Participants underwent annual CMR, echocardiography, and laboratory testing over 2 years (3 time points). Laboratory tests were performed on the same day as CMR and included complete blood count, fetal Hb, renal and hepatic panels (including serum creatinine, hepatic enzymes, and bilirubin), cystatin C, aldosterone, and plasma renin activity. The hematocrit obtained on the same day as CMR was used to calculate ECV. All CMR and study procedures were performed at steady-state, at least 1 month after any acute SCA-related event and 3 months after the last transfusion. Relevant clinical data, including acute SCA-related complications (such as vaso-occlusive pain crisis or acute chest syndrome) that required office visit, emergency department care, or inpatient treatment, and acute blood transfusions, were extracted from the electronic medical records for the year preceding each CMR scan.

CMR imaging protocol

All baseline and follow-up ECV measurements were independently assessed by at least 2 experienced cardiac imaging specialists. In cases in which ECV values differed by ≥5% between readers (7/67 scans), the images were reevaluated, regions of interest were redrawn, and ECV was reconciled by consensus. Final ECV values used in the study represent the average of the 2 readers’ measurements.

Echocardiography and diastolic function classification

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed with a Philips iE-33 system (Philips Electronics, Andover, MA). Measurements were analyzed using a cardiology analysis system (Digisonics, Houston, TX). Diastolic function was assessed using pulsed-wave Doppler of mitral and tricuspid inflow velocity peak at early (E) and late (A) filling, tissue Doppler imaging of the lateral and septal annular velocities in early (e′) and late diastole (a′), and continuous-wave Doppler sampling of the tricuspid valve to measure tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity (TRV). Agitated saline was used to enhance TRV measurements.

We used the same modified diastolic function classification criteria as in the previous baseline analysis of this cohort.5,24 Briefly, patients classified to have diastolic dysfunction must have all 3 abnormalities: left atrial (LA) volume enlargement, reduced lateral e′ (z score less than −2), and elevated E:e′ ratio (z score greater than +2) for age and body surface area. Patients with normal diastolic function do not have LA enlargement, diastolic abnormalities, or TRV elevation. Inconclusive classification comprised participants with LA enlargement and only 1 additional abnormality (either abnormal e′, E:e′ ratio, or TRV of ≥2.8 m/s)

Statistical analysis

Comparisons across groups were performed using 1-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey multiple comparisons test. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was used based on variable distribution.

Longitudinal associations with ECV were assessed using linear mixed-effects regression models, incorporating statistically significant covariates from univariate analysis plus demographic characteristics. To limit overfitting given our sample size, variables were grouped into domains (clinical/demographics, laboratory, and imaging). Variance inflation factor was used to assess multicollinearity, and variables with variance inflation factor of >5 were excluded.

Random intercepts and, when appropriate, random slopes for time were included to account for variability within patients. Mixed-effects models were fitted using the “lmer()” function from the “lme4” package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

All other statistical analyses and graphing were performed using Prism 10.1.4 for macOS (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA). P values of <.05 from 2-sided tests were considered statistically significant. There was no study-wide correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Results

Characteristics of the longitudinal cohort

A total of 26 patients were enrolled in the study. Of these, 24 had at least 2 evaluable CMR studies and were included in the longitudinal analysis. Seventeen participants had all 3 CMR studies, whereas 7 had only 2 evaluable studies due to missing postcontrast T1 maps (motion artifact or incomplete study). The mean interval between baseline and year 1 CMRs was 12.2 ± 0.4 months, and between year 1 and year 2 was 13 ± 3 months. The mean age at first CMR was 21.4 ± 10 years (range, 6-48), with 11 of 24 patients (46%) being male, and 11 (46%) aged <18 years (pediatric).

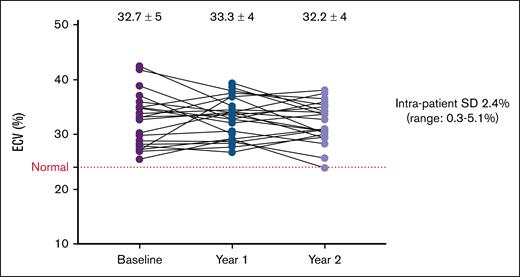

Stability and variability of ECV measurements over time

The annualized mean change in ECV was −1.1% ± 2.7% per year. There were no significant changes in ECV across the 3 time points. Mean ECV values were: baseline (32.7% ± 5%), year 1 (33.3% ± 4%), and year 2 (32.2% ± 4%). As a percentage change from baseline value, ECV changed by −0.8% ± 14% from baseline to year 1, and by −1.3% ± 11% from year 1 to year 2 (Table 1).

Intrapatient variability in ECV (standard deviation) ranged from 0.3% to 5.1%, with a mean of 2.4% (Figure 1). There was no difference in intrapatient variability between pediatric and adult patients (2.3% vs 2.5%; P = .78) or between males and females (2.3% vs 2.5%; P = .76). There were also no significant differences in ECV change between pediatric and adult participants (P = .16), or between males and females (P = .08).

Individual ECV trajectories over time. Individual patient trajectories of ECV over time, from baseline to year 1 and year 2. Each line represents a single patient. Mean ECV values ± SD are shown at each time point. The dotted horizontal line indicates the upper limit of normal ECV (25%). SD, standard deviation.

Individual ECV trajectories over time. Individual patient trajectories of ECV over time, from baseline to year 1 and year 2. Each line represents a single patient. Mean ECV values ± SD are shown at each time point. The dotted horizontal line indicates the upper limit of normal ECV (25%). SD, standard deviation.

Longitudinal changes in laboratory parameters, CMR, and echocardiographic metrics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, no statistically significant changes were observed in these variables or in pattern of disease-modifying therapy prescription over the 2-year duration of the study. Patients on chronic transfusions were excluded and all T2∗ measurements were normal, indicating absence of myocardial hemosiderosis.

Increases in ECV measurements were strongly associated with an increase in extracellular matrix volume index (β = 0.77; P < .001) and not by cellular volume index change (β = −0.2; P = .35). Over time, only extracellular matrix volume index remained significantly associated with ECV but not cellular volume index (P < .001 and P = .08, respectively). Together, this suggests that ECV measurements are more representative and strongly driven by changes in extracellular matrix than by myocardial cellular changes.

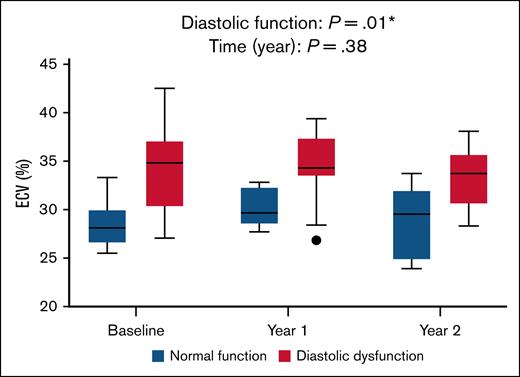

Association between ECV and diastolic dysfunction

At baseline, 7 patients had normal diastolic classification, 10 had inconclusive classification, and 7 had diastolic dysfunction. Diastolic classification remained largely stable over time. No participant classification changed directly from normal to diastolic dysfunction or vice versa. However, 5 participants had a change in classification: 3 were reclassified upward (2 from normal to inconclusive, and 1 from inconclusive to diastolic dysfunction), and 2 were reclassified downward (1 from diastolic dysfunction to inconclusive, and 1 from inconclusive to normal).

The association observed between diastolic dysfunction and higher ECV at baseline was maintained throughout the study. ECV was significantly higher in patients with diastolic dysfunction than those with normal diastolic function at all 3 time points (P = .01; Figure 2). However, neither time (P = .38), nor the interaction between diastolic dysfunction and time (P = .85) was significant, likely reflecting overall stability in ECV and diastolic classification over 2 years. The results remained significant when diastolic function was analyzed in 3 groups (normal, inconclusive, and diastolic dysfunction; P = .006).

Relationship between ECV and diastolic dysfunction over time. Longitudinal comparison of ECV between patients with normal diastolic function (blue boxes) and those with diastolic dysfunction (red boxes) across 3 time points. A mixed-effects model demonstrated a significant overall difference in ECV based on the presence of diastolic dysfunction (P = .001), with no significant effect of time (P = .38) or time × diastolic dysfunction interaction (P = .85), indicating that group differences in ECV were consistent over time.

Relationship between ECV and diastolic dysfunction over time. Longitudinal comparison of ECV between patients with normal diastolic function (blue boxes) and those with diastolic dysfunction (red boxes) across 3 time points. A mixed-effects model demonstrated a significant overall difference in ECV based on the presence of diastolic dysfunction (P = .001), with no significant effect of time (P = .38) or time × diastolic dysfunction interaction (P = .85), indicating that group differences in ECV were consistent over time.

Intrapatient changes and ECV

Analysis of intrapatient changes in all study variables showed a trend between changes (Δ) in cardiac index, LV mass index, reticulocyte count, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and extracellular matrix volume index with ΔECV (P < .1). All variables with P value <.1 were included in a multivariate model.

ΔLV mass index and change in extracellular matrix volume index remained significant in this model. However, when time was included as a covariate, these associations lost statistical significance, suggesting that although intrapatient variation in LV mass and extracellular matrix volume were related to ECV changes, their effect does not vary over time (Table 2).

Longitudinal associations with ECV

In univariate analysis, several variables were significantly associated with ECV across all time points, including clinical measures (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, presence of diastolic dysfunction, and a trend with acute care visits [P = .05]); imaging parameters (LA volume index [LAVi], left and right ventricular end-diastolic volume indices, native T1, indexed extracellular matrix volume, and peak MPA velocity); and laboratory variables (Hb, hematocrit, fetal Hb, reticulocyte count, NT-proBNP, and direct bilirubin; Table 3).

In multivariate mixed-effects models in which variables were combined thematically into 3 groups (clinical and demographic variables, cardiac imaging parameters, and laboratory parameters), diastolic dysfunction, Hb, NT-proBNP, LAVi, and peak MPA velocity retained independent longitudinal associations with ECV (Table 3).

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of children and adults with SCA, we found that ECV measured by CMR is a stable and reliable biomarker over a 2-year period. Although elevated ECV was nearly universal and consistent with previous cross-sectional studies, this is, to our knowledge, the first study to demonstrate its temporal stability in individuals with unchanged SCA therapy and without antifibrotic treatment, supporting its utility as a biomarker for disease monitoring and a benchmark for evaluating antifibrotic therapies.

Our data reinforce the central role of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in the pathogenesis of SCA cardiomyopathy. The strong and consistent association between elevated ECV and echocardiographically defined diastolic dysfunction across all time points suggests that myocardial fibrosis contributes meaningfully to impaired relaxation and elevated filling pressures. Importantly, neither ECV nor diastolic classification changed substantially over time across patients, supporting that myocardial remodeling in SCA is a chronic, slowly progressive process, at least in the absence of targeted interventions. Although the impact of disease-modifying therapy on myocardial fibrosis in SCA remains uncertain,17,25 unlike focal replacement fibrosis, diffuse myocardial fibrosis is potentially reversible and represents a modifiable therapeutic target.26-29

A key strength of this study is the quantitative separation of myocardial tissue into the cellular and extracellular compartments.28,30 ECV represents the fraction of myocardial tissue occupied by the extracellular space. Accordingly, ECV can increase either due to expansion of the extracellular compartment (eg, fibrosis or edema) or reduction in the cellular compartment (eg, myocyte loss). Conversely, ECV may remain unchanged despite progression of fibrosis if the extracellular expansion is proportionally matched by an increase in cellular mass. In our study, myocardial cellular volume indices were lower than published adult normal ranges,31 but because our cohort included a broad age range, including children, it remains unclear whether increased myocardial mass in SCA is explained solely by extracellular expansion. Age-matched normative values are needed to definitively determine whether cellular volume remains within normal limits. Nonetheless, our study shows that changes in ECV over time are more strongly associated with extracellular matrix volume than with myocardial cellular volume, indicating that ECV accurately reflects fibrotic remodeling rather than simply fluctuations in LV mass. These results highlight the biological specificity of ECV and support its validity as a mechanistic biomarker of myocardial fibrosis. The ability to noninvasively quantify both the cellular and the extracellular compartments offers a unique opportunity to monitor cardiac remodeling and assess response to antifibrotic therapies.

Furthermore, multivariate modeling identified several clinical and imaging correlates of ECV, including Hb concentration, NT-proBNP, LAVi, and peak MPA velocity. Each of these variables has known associations with cardiac stress, diastolic dysfunction, volume overload, or pulmonary hypertension, all of which may contribute to, or result from, myocardial fibrosis.32-36 The independent association between ECV and NT-proBNP, a validated predictor of early mortality in SCA,37 further supports the potential prognostic relevance of ECV in this population. These findings suggest that ECV may serve as a biomarker of disease severity. Future studies should evaluate additional associations with albuminuria or interleukin-18, and whether combining ECV with functional biomarkers such as NT-proBNP or echocardiographic parameters could enhance risk stratification and guide therapeutic interventions.

In our study, peak MPA velocity was positively associated with ECV, a novel and intriguing finding. This relationship may reflect the combined effects of volume overload, lower pulmonary vascular resistance, and the high prevalence of pulmonary venous hypertension in SCA, which together increase forward pulmonary arterial flow in contrast to pulmonary arterial hypertension, in which peak MPA velocities are reduced.38-40 Myocardial fibrosis may lead to diastolic dysfunction and secondary pulmonary venous hypertension causing pulmonary flow changes and increased peak MPA velocity. Conversely, pulmonary hemodynamic stresses could promote extracellular matrix expansion over time and myocardial fibrosis, especially in the right ventricle,4 linking pulmonary vascular changes to cardiac remodeling. Together, these findings suggest a possible bidirectional relationship between myocardial fibrosis and pulmonary vascular changes. Although the mechanisms remain uncertain, this association highlights a potential interaction between pulmonary and myocardial pathology in SCD and warrants further investigation.

The independent longitudinal association between anemia and ECV corroborates our earlier cross-sectional findings and points to a potentially important mechanistic link in SCA cardiomyopathy. Although myocardial fibrosis has been shown to be specific to sickle Hb in mouse models, this relationship has not yet been extensively studied in humans.3 In patients with SCA, anemia could plausibly serve as a surrogate marker of disease severity or could directly influence myocardial remodeling through mechanisms independent of fibrosis such as volume overload, altered capillary density, or changes in myocardial perfusion. Although the contribution of the intravascular space to ECV measurements is typically small, in SCA it is possible that vascular remodeling could lead to a greater contribution. Regardless of the precise mechanism, persistently elevated ECV remains a concerning finding because it reflects abnormal cardiac tissue characteristics that may indicate maladaptive remodeling or a chronic hemodynamic response to anemia.

ECV may serve as an intermediate biomarker of long-term cardiovascular risk in this population, bridging the gap between early subclinical changes and overt clinical outcomes such as heart failure, arrhythmias, or death.41-43 Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of fibrosis and ECV elevation in SCA is a crucial step toward treatment. Whether the activation of profibrotic pathways is triggered by cardiomyocyte death, myocardial inflammation, or other forms of cellular stress, these stimuli converge on common fibrogenic signaling cascades that promote extracellular matrix expansion and fibrosis.8 Mechanistic studies that dissect these upstream triggers and downstream fibrotic responses are needed to clarify the role of anemia and other processes in the pathogenesis of myocardial fibrosis and to identify opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Importantly, we observed low intrapatient variability in ECV measurements (mean, 2.4%), which is consistent with the natural history of ECV stability in other disease states, typically ranging from 1.9% to 3% depending on the condition and duration of follow-up.44-46 Notably, ECV variability did not differ significantly between pediatric and adult patients, nor between sexes, indicating that ECV is a stable and reproducible measure across key subgroups. This low variability supports the feasibility of using ECV as a surrogate endpoint in future clinical trials, particularly those evaluating antifibrotic or cardioprotective interventions. ECV offers several advantages over traditional cardiac biomarkers in clinical studies: it directly reflects myocardial fibrosis, eliminates the need for invasive cardiac biopsies, and may reduce required sample sizes due to its measurement precision. Unlike nonspecific cardiac biomarkers, ECV may serve as a superior efficacy endpoint (eg, in phase 2 studies) by capturing pathophysiologically relevant changes in myocardial tissue structure.20

This study has several limitations. The sample size is modest and may limit the generalizability of findings or the detection of small but clinically meaningful changes. Additionally, although the study was prospective, therapeutic interventions were not introduced, and the cohort was observational; thus, the predictive utility of ECV changes remains to be validated in interventional studies. Also, diastolic classification, although robust, was based on noninvasive echocardiographic criteria and may not reflect invasive hemodynamic measurements. Moreover, we identified image quality, which improved over the conduct of this study, as an important criterion for accurate determination of ECV.47 Although all scans were independently analyzed by 2 experienced reviewers, in 7 of 68 scans, each involving poor image quality or motion artifact, the interobserver difference exceeded 5 points, necessitating reevaluation and consensus review. For future CMR studies, continuous quality monitoring and improvement will be needed to ensure reproducibility and reliability of ECV measurements.

Finally, we reanalyzed our earliest (baseline) scans5 using our current processes described here. Consequently, the revised ECV values were systematically but modestly lower than originally reported. All values were lower in approximately the same proportion. These early images were of lower quality than more recent scans. The adoption of standardized, adjudicated image analysis and enhanced postprocessing protocols have increased our confidence in the revised measurements, which now align more closely with other reports of ECV values in individuals with SCA.17,18 Crucially, all patients still had abnormally elevated ECV at baseline, and all previously reported associations between ECV and relevant clinical markers, including Hb, diastolic dysfunction, and NT-proBNP, remained statistically significant. Thus, despite the downward revision in absolute ECV values, the original associations and study conclusions remain unchanged (supplemental Figure 1).

In conclusion, ECV measured by CMR is a reliable, stable, and biologically relevant measure of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in SCA. Its association with diastolic dysfunction and other markers of cardiac stress supports its use as a noninvasive surrogate endpoint in clinical trials aimed at preventing or reversing cardiac remodeling in SCA. We plan to validate ECV as a biomarker of treatment response in human mechanistic and interventional studies by targeting myocardial fibrosis pharmacologically.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Shova, Amanda Pfeiffer, and the clinical research team at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for their assistance with recruitment of participants and collection and analysis of clinical data.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Excellence in Hemoglobinopathy Research Award program U01HL117709 [P.M. and C.T.Q.]), an ASH Research Collaborative Investigator-Initiated Protocol award, and a Procter Scholar award (O.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: O.N., M.D.T., P.M., and C.T.Q. designed the study; O.N., C.T.Q., and M.T. were responsible for patient enrollment and study procedures; C.E.M., S.H., T.A., M.D.T., and S.M.L. were responsible for cardiac imaging supervision, acquisition, and analysis; O.N. and C.T.Q. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Omar Niss, Division of Hematology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, MLC 7015, Cincinnati, OH 45229; email: omar.niss@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Omar Niss (omar.niss@cchmc.org), or author Charles T. Quinn (charles.quinn@cchmc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.