Key Points

Hydroxyurea use in kids with SCD is linked to higher sleep oxygen levels but not fewer sleep disturbances such as OSA.

Despite therapy, children with SCD still face poor sleep quality and oxygen drops and the causes remain unclear.

Visual Abstract

Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) have a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances than the general population. Disease-modifying therapies, such as hydroxyurea aim to reduce SCD complications. The impact of disease-modifying therapies on SCD sleep remains unclear. We hypothesized that hydroxyurea would increase nocturnal oxygen saturation, improve sleep quality, and decrease degree of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This retrospective cohort included 425 children with SCD aged 1 to 18 years who underwent 662 polysomnograms (PSGs) between 2013 and 2023. Children were group by therapy status (no therapy vs hydroxyurea). Sleep data were abstracted from PSGs and clinical metadata collected. At first PSG, peripheral oxygen saturation levels were significantly higher during rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) sleep in the hydroxyurea group (P < .001). Multivariable regression revealed hydroxyurea was independently associated with higher NREM (β = 1.88; P = .001) and REM (β = 1.69; P = .005) oxygen saturation nadir. Apnea hypopnea index and other parameters did not differ between the groups. Among 135 children with repeat PSGs, modeling demonstrated lower baseline peripheral oxygen saturation (difference, −0.93; P = .027) in the hydroxyurea group with no other significant differences. Hospitalization rates for asthma, vaso-occlusive episodes, and acute chest were not associated with changes in PSG parameters over time. Children with SCD on hydroxyurea demonstrated higher oxygen saturation during sleep but persistent abnormalities, including OSA, oxygen desaturations, and decreased sleep efficiency. Underlying factors for persistent sleep abnormalities remain undetermined.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic hemoglobinopathy that can lead to complications including chronic hemolytic anemia, acute chest syndrome (ACS), and vaso-occlusive episodes (VOEs). These complications occur due to the polymerization of abnormal sickle hemoglobin (Hb) under low oxygen (O2) conditions.1,2 Another underexplored complication of SCD is sleep-related breathing disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).3 Recent studies show a wide range of OSA prevalence in children with SCD (5%-79%), whereas in the general pediatric population, it is significantly lower (1%-5%).3,4 Children with SCD are thought to be at higher risk for OSA due to factors including adenotonsillar hypertrophy, chronic inflammation, and increased upper airway obstruction.4,5 OSA in children with SCD is of special concern as it is correlated with nocturnal hypoxemia, which may lead to red blood cell sickling and increased hospitalizations for ACS or VOEs.6

One of the recommended preventive SCD therapies is hydroxyurea (HU), which increases the production of fetal Hb (HbF) and was US Food and Drug Administration approved for children in 2017. HbF has an increased affinity for O2, therefore reducing the risk of hemolysis and frequency of VOEs and ACS.7,8 In recent years, other disease-modifying therapies have been developed, including voxelotor and crizanlizumab, which inhibit the polymerization of sickle Hb and reduce pain episodes by inhibiting P-selectin, respectively.9,10 A retrospective study of 141 children found that HU therapy status was associated with higher awake and nocturnal peripheral oxygen saturations (SpO2), but no significant correlation was observed between therapy status and prevalence or degree of OSA.11 Furthermore, there remains limited evidence looking at effects of disease-modifying therapies on OSA and other sleep parameters.

This study focuses on understanding how disease-modifying therapies affect sleep-related outcomes, such as nocturnal hypoxemia, apnea hypopnea index (AHI), sleep efficiency, and arousal index, and the relation of changing sleep parameters with the frequency of hospitalizations in children with SCD. We hypothesized that improved oxygenation and reduced hemolysis associated with SCD therapies would reduce the severity of OSA, improve sleep quality, and potentially influence hospitalization rates from SCD complications. The findings could provide new insights into optimizing management strategies for children with SCD and sleep dysfunction, with the goal of reducing morbidity and improving overall quality of life.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study investigating the impact of HU on sleep-disordered breathing in children with SCD. Children with a diagnosis of SCD aged 1 to 18 years who underwent polysomnograms (PSG) between 1 January 2013 and 31 July 2023 at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta were included. Screening PSGs were indicated for persistent or evolving snoring/sleep-disordered breathing, daytime O2 saturations <95%, snoring plus nocturnal enuresis, or other clinician concerns. Follow-up PSGs were indicated for surgical follow-up after adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy, persistent OSA without surgical intervention, or escalation of sleep-disordered breathing symptoms. PSGs were performed in a dedicated outpatient sleep laboratory, with interpretations by pediatric sleep providers.

Sociodemographic and clinical data, including age, race, sex, SCD genotype, body mass index (BMI), medications for SCD, length of time on treatment, previous airway surgeries, and number of annual hospitalizations for asthma, VOEs, or ACS, were extracted from electronic medical records for analysis. Active HU at time of PSG was noted as a time-varying covariate. Electronic extraction was confirmed by manual chart review. OSA was determined according to standard pediatric definitions (mild OSA with AHI of 1 to <5 events per hour, moderate OSA with AHI 5 to <10 events per hour, severe OSA with AHI of ≥10 events per hour). Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Institutional Review Board provided approval, with an exemption for informed consent based on the retrospective study. This study abides by the rules of the recently revised Declaration of Helsinki protocol.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Children with incomplete PSG data, noninvasive ventilation (continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure), supplemental O2 during the study, chronic transfusion therapy, or <2 hours of recorded sleep during the PSG were excluded. Children were categorized into therapy groups: no therapy, HU, crizanlizumab, and dual therapy (HU and crizanlizumab). Groups with <10 children were excluded from analyses, which left only a comparison of HU or no therapy. On the basis of institutional protocols, HU was offered to all study participants as infants, but some choose not to initiate until later in life. Patients were on HU for a minimum of 3 months before study inclusion, with an average time of 5.03 years for the cohort.

Outcome variables

Primary outcomes included O2 saturation nadir during nonrapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, total AHI, obstructive hypopnea index (OHI), the percentage of total sleep time spent with O2 saturation <90%, sleep efficiency, and arousal index. Secondary outcomes included the number of annual hospitalizations for asthma, VOEs, and ACS, classified by ICD-10 codes and local diagnostic protocols coded by the treating physician. If a visit contained >1 diagnosis (eg, VOE and ACS), these were separately counted.

Statistical analysis

Owing to the low sample size in 2 therapy patterns (dual therapy and others), the primary therapy groups studied were between HU and no-therapy groups. Two-sample t tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables were used to compare demographic and outcomes variables between the 2 primary therapy groups (HU vs no therapy). Multivariable regression models were fit to investigate the association between the 2 primary therapy groups, after adjusting for clinically and statistically relevant covariates. The complete set of confounders considered in the final models included patient sex, genotype, and the following data noted at the time of PSG: patient age, sex, genotype, Hb value (grams per deciliter), and BMI. In the rare instance when BMI or Hb level was not immediately available at PSG date, values within 3 months were used. Genotype was recoded as dummy variables, with genotype HbSS as the reference level.

The number of annual hospitalizations for asthma, VOEs, and ACS was summed across 5 years and analyzed as count data. Zero-inflated Poisson regression models were used for analysis. For analysis of repeated visits only, the average values within each therapy group and visit were plotted for the primary continuous outcomes. The primary continuous outcomes were analyzed through mixed effects models where therapy group, time point, and the interaction between therapy group and time point were treated as fixed effects. The models used an unstructured covariance structure and random intercepts to account for within-patient repeated measures.

A P value <.05 was considered significant, and tests were 2 sided. All data management, statistical analyses, and figure generation were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort selection and characteristics

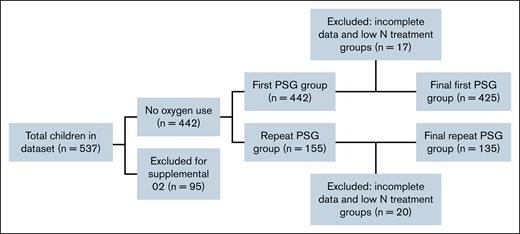

A total of 537 children with SCD and 899 associated PSGs were initially identified. However, 95 children were excluded for receiving supplemental O2 during PSG, and 9 were excluded for incomplete data (having <2 hours of recorded sleep) or absent PSG records, leaving 433 children for “first visit only” analysis. Two therapy groups that had <10 children (crizanlizumab alone and HU plus crizanlizumab, n = 8) were further excluded, resulting in 425 children for analysis (Figure 1). There were 0 children on voxelotor who met inclusion criteria.

As found in Table 1, among 425 children in the main analysis (no therapy, 138; HU, 287), 52.5% were female and 47.5% were male, with no significant difference by therapy status (P = .46). Genotype distributions did not differ among the groups, with most individuals having HbSS. Mean age at PSG was higher in the HU group (10.21 ± 4.62 years) vs the no-therapy group (8.70 ± 4.75 years; P < .001). Adenoidectomy or tonsillectomy before PSG was <10% in both groups. Mean Hb concentration and BMI were similar among the groups.

First visit analyses of sleep parameters

Approximately 50% of the entire cohort had OSA, with a slightly higher proportion in the no-therapy group (P = .05; Table 2). When analyzing sleep parameters at first PSG by univariable analysis, mean SpO2 nadir during NREM (P < .001) and REM (P < .001) were significantly higher in the HU group, despite similar baseline SpO2 levels (96.2% vs 95.9%). Other sleep parameters, such as AHI, OHI, and total sleep time, were not different between the 2 groups at the first visit, although trends in reduced AHI and OHI were noted in the HU group. Notably, sleep efficiency was only 83%, and arousal rates were >8 in both groups, indicative of reduced sleep quality.

Multivariable regression for first visit analysis

To assess therapy effects after adjusting for possible confounders, multivariable regression models were used for the primary continuous outcomes of age, sex, genotype, BMI, and Hb as found in Table 3. HU therapy was independently associated with higher O2 saturations during both NREM (β = 2.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00-3.29; P < .001) and REM (β = 1.95; 95% CI, 0.77-3.13; P < .001) sleep after adjusting for covariates. In contrast, HU therapy was not linked to significant changes in total sleep time, sleep efficiency, arousal index, or AHI measures. Shared covariates among NREM and REM models included sex, Hb level, and the presence of snoring.

Repeat visit analyses

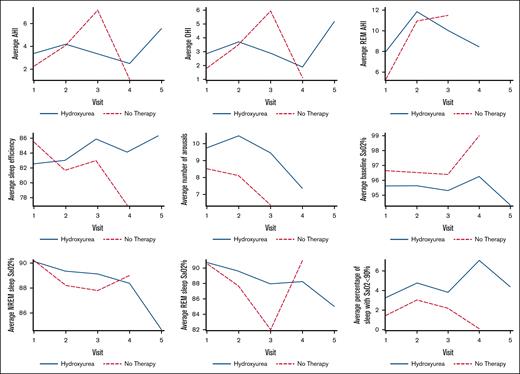

Of the 155 children who had multiple PSGs, 11 were excluded (based on the same criteria as first visit analysis, including supplemental O2 use or noninvasive ventilation), and low sample size groups were also excluded as previously discussed leaving 135 children with 323 PSGs for longitudinal assessment. Figure 2 spaghetti plots illustrate PSG parameters over time for both groups, and Table 4 shows counts of individuals on HU with improved, no change, or worsened PSG parameters (OSA, O2 saturation, sleep efficiency) associated with time. Table 4 also shows the 10 individuals who had tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (TA) in between baseline and follow-up studies, with no clear trends across the response groups. These data highlight significant variability in sleep parameters over time, regardless of group. A mixed effects model was used to analyze individuals with repeat PSGs for the primary outcomes. The HU group was found to have a lower average resting baseline SpO2 percent (difference, −0.93; 95% CI, −1.75 to −0.11; P < .027) at the time of repeated PSGs (Table 5). Arousals trended higher in the HU group (P = .14). There were no significant differences in AHI, OHI, total sleep time, or sleep efficiency when evaluated over multiple PSG visits between groups, a similar finding to that of single visits.

Spaghetti plots of changes in PSG parameters over time for children with SCD and repeated PSGs in no-therapy (red) vs hydroxyurea (blue) groups. PSG parameters include averages for AHI, OHI, REM AHI, sleep efficiency, arousals, baseline SpO2 percent, NREM and REM SpO2 percent nadirs, and percentage of sleep with O2 desaturations <90%.

Spaghetti plots of changes in PSG parameters over time for children with SCD and repeated PSGs in no-therapy (red) vs hydroxyurea (blue) groups. PSG parameters include averages for AHI, OHI, REM AHI, sleep efficiency, arousals, baseline SpO2 percent, NREM and REM SpO2 percent nadirs, and percentage of sleep with O2 desaturations <90%.

Hospitalization outcomes

Zero-inflated Poisson models of annual hospitalizations for asthma, VOEs, or ACS did not reveal any consistent associations between changing PSG parameters over time and hospitalization rates among the HU group.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study evaluated the impact of disease-modifying HU on sleep-disordered breathing in a large cohort of children with SCD. Contrary to the initial hypothesis, HU therapy did not demonstrate improvements in important sleep parameters, including AHI, OHI, arousal index, or sleep efficiency. Although O2 saturations during NREM and REM sleep were higher in children on HU, overall desaturation time was similar between the groups. Such persistent abnormalities highlight the challenges optimizing sleep in this population, even when disease-modifying therapies are in place. The results are also in contrast to recent studies from smaller cohorts,12,13 highlighting the need for large, registry-based studies in SCD and the lack of a nationally accessible database akin to other disorders such as cystic fibrosis.

These findings add to the current literature illustrating on how sleep disturbances are common in children with SCD, including OSA, decreased sleep efficiency, and nocturnal hypoxemia.14,15 A recent multicenter study by Alishlash et al involving 210 children with SCD demonstrated that nearly half (47%) had OSA, and significant proportions had abnormal arousal indices, low nocturnal O2 saturations, and elevated periodic limb movements, all consistent with disturbed sleep architecture.12 Gillespie et al emphasized the broad pulmonary complications common in pediatric SCD, including sleep-disordered breathing, and highlighted the need for a comprehensive approach to management and early detection.16 Abramson et al explored the complex interactions between SCD, sleep-disordered breathing, and HU therapy, revealing associations between HU use and improved sleep parameters, potentially mediated through reduced systemic inflammation and improved hematologic parameters, such as elevated HbF and lower white blood cell counts.13 Despite these promising findings, this study did not identify clinically significant improvements in most sleep parameters associated with HU therapy. This discrepancy may be due to underlying differences in patient populations, differences in sample sizes, or confounding factors such as adherence to therapy, which could not be strictly assessed. Similar to Abramson et al,13 variability was observed in the severity of sleep disruptions across patients, reinforcing the idea that individual disease characteristics and therapy responses can vary significantly.

Persistent sleep abnormalities despite HU use in our cohort suggest that the initial extent or persistence of underlying disease can affect the efficacy of HU on sleep in children with SCD. This disease severity could have masked any potential benefit from therapy, particularly from the known mechanism of HU, which provides improvements in O2 delivery related to increased HbF.7,8,13 Other factors such as pain, poorly controlled asthma, or adenotonsillar hypertrophy could also have played a role, acting as independent contributors to worsened sleep. Recognizing and addressing these factors is important as part of a comprehensive care plan.

There are several limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. Although the cohort intended to include some patients treated with newer agents such as crizanlizumab and dual-therapy regimens, the small sample sizes prevented inclusion for statistical comparisons. This is an area that deserves further exploration because these newer therapies could have a different impact on sleep outcomes. Another limitation involves potential confounding by indication for starting HU. Despite clinical practice guidelines and local protocols that offer all patients HU preventively as infants, some may choose to wait to initiate until more severe complications arise, discontinue due to side effects, refuse due to drug stigma, or have other predisposing factors limiting therapy initiation that could influence outcomes. The retrospective design did not allow reliable assessment of other potential confounders such as longitudinal changes in BMI, adenotonsillar hypertrophy status, lung function, or asthma control. Last, the timing between PSGs was also variable, as an institutional protocol guiding repeat sleep studies was only recently implemented.

Despite these limitations, meaningful clinical implications were found. The findings suggest that HU treatment alone is unlikely to fully resolve sleep-disordered breathing issues. Thus, clinicians should remain vigilant in screening for and managing sleep problems in this population.17,18 Sleep dysfunction should be treated as its own important clinical target, not just as a secondary effect of SCD. Multidisciplinary care involving hematology, pulmonology, and sleep medicine is critical to these efforts, especially given recent evidence that multidisciplinary care models can improve detection of sleep issues and decrease hospitalizations in children with SCD.16,18,19 It is also important to set realistic expectations with families, explaining that although HU has many benefits, improved sleep quality may not be one of them. Furthermore, sleep issues still need to be actively monitored while on HU and other contributing comorbidities addressed, such as obesity and sleep hygiene.

Moving forward, prospective studies may be helpful to further investigate the hypothesis, ideally with standardized intervals between PSGs and careful tracking of medication adherence and development of comorbidities. It would also be valuable to investigate the interactions between sickle cell lung disease and sleep-disordered breathing to better understand how these factors modify SCD severity.20 Developing targeted screening protocols for OSA and nocturnal pain-related sleep disturbances could be another important step to facilitate earlier identification and intervention.16,17,19 Alishlash et al also emphasized the need for consistent protocols and standardized interpretation of PSG findings across centers, as they found substantial variation in sleep outcomes depending on institution, demographics, HU use, and age of screening. Implementing standardized protocols across SCD centers will help improve care.12 Overall, early detection and comprehensive management have the potential to improve quality of life for these children. Multidisciplinary collaboration and a proactive approach to sleep evaluation are critical to optimizing outcomes in this vulnerable and often medically complex population.

In summary, children on the disease-modifying agent HU demonstrated improved nocturnal O2 levels but did not demonstrate clinically significant improvements in other polysomnographic findings. Underlying factors for persistent sleep abnormalities in children with SCD remain to be determined.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01HL178923) (B.T.K.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.Y. and B.T.K. designed, analyzed, and wrote the manuscript; S.B. participated in study design and conducted statistical analyses; G.K. and L.A. participated in data extraction; T.H. participated in statistical analyses; C.D., M.G., S.V., K.K., and R.L. participated in study design and data review; and all authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Benjamin T. Kopp, Emory University School of Medicine, 2015 Uppergate Dr, Atlanta, GA 30322; email: benjamin.t.kopp@emory.edu.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Benjamin T. Kopp (btkopp@emory.edu).