Key Points

PIEZO1- and KCNN4-HX RBCs show distinct differences in functional and metabolic properties.

Ex vivo PK activation leads to increased energy levels, but it does not evidently improve hydration in PIEZO1-HX.

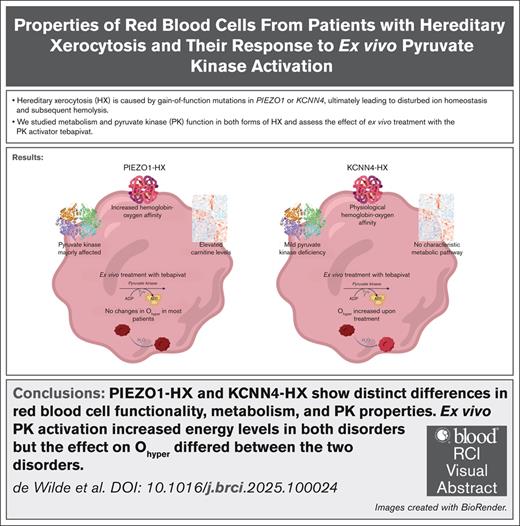

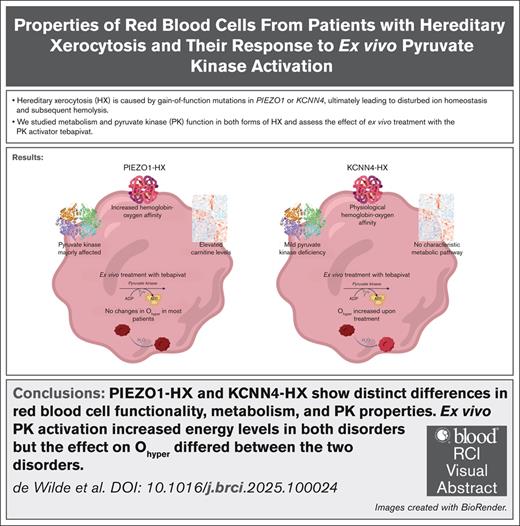

Visual Abstract

Hereditary xerocytosis (HX; also known as dehydrated stomatocytosis) is a rare red blood cell (RBC) disorder associated with hemolysis and iron overload. Gain-of-function mutations in either PIEZO1 or KCNN4 lead to disturbed RBC ion homeostasis. PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX are mechanistically different and have distinct phenotypes, yet these differences are poorly understood. Here, we study RBC hydration and metabolism in 12 patients with PIEZO1-HX, 3 patients with KCNN4-HX, and 10 controls, with particular focus on the key glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase (PK). In PIEZO1-HX, RBC PK activity is relatively decreased (PK-to-hexokinase ratio, 4.7 vs 8.4 in controls), along with a decrease in PK thermostability (43.6% vs 77.8%) and PK protein levels. KCNN4-HX RBCs show a less pronounced decrease in activity (PK-to-hexokinase ratio, 6.3) and thermostability (64.7%), with no decrease in protein levels. Untargeted metabolomics demonstrated distinct differences in various metabolites, including carnitines, in PIEZO1-HX vs KCNN4-HX or controls. Interestingly, hydration (Ohyper) of PIEZO1-HX RBCs correlated negatively with the ratio of adenosine triphosphate to 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (r = –0.839). To evaluate whether enhancing glycolysis by PK activation could improve hydration, we treated RBCs ex vivo with the PK activator tebapivat. This treatment increased PK activity (>40%) in both disorders, but it did not negate dehydration in most PIEZO1-HX RBCs. In contrast, Ohyper did improve in KCNN4-HX (>10 mOsm/kg increase). Our results indicate significant metabolic differences between PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX and different responses to ex vivo PK activation. Our findings increase the understanding of the differences between PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX and provide evidence for a potential response to PK activator treatment.

Introduction

Hereditary xerocytosis (HX; also known as dehydrated stomatocytosis) is a rare autosomal dominant red blood cell (RBC) disorder, which is associated with hemolysis and iron overload. HX is caused by mutations in PIEZO1 (OMIM number: 194380), which encodes the mechanosensitive cation channel Piezo1,1,2 or KCNN4 (OMIM number: 616689), which encodes the Gardos channel.3-6 Gain-of-function mutations in PIEZO1 lead to increased intracellular calcium levels.3,7-9 The rise in intracellular calcium activates the Gardos channel, eventually resulting in the loss of potassium and water. Similarly, gain-of-function mutations in KCNN4 result in overactivation of the Gardos channel,3 leading to disturbed ion homeostasis without evident dehydration, as assessed by osmotic gradient ektacytometry. In both disorders, RBCs show decreased deformability, resulting in premature splenic clearance.10

Patients with PIEZO1-HX often present with compensated hemolysis as well as marked reticulocytosis and iron overload. Patients with KCNN4-HX typically present with a less compensated hemolytic anemia but may also have iron overload.3,11 Given that the phenotype of HX varies considerably and shares similarities with other hemolytic anemias, diagnosis can be challenging and patients may be underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.6,12,13 Osmotic gradient ektacytometry is a technique used to diagnose HX, and patients with PIEZO1-HX typically show a left-shifted curve, reflecting decreased RBC hydration. This left shift is usually absent in KCNN4-HX.4,14 To confirm the diagnosis of HX, DNA analysis generally is required. Treatment options are limited to supportive care with folate administration, with RBC transfusions in rare cases. Iron overload is treated with phlebotomies or iron chelation, similar to other hemolytic anemias.15 Importantly, unlike other forms of hereditary hemolytic anemia, splenectomy is contraindicated in HX due to a strongly increased risk of thrombosis.11,16-18 Notably, due to the hematologic and phenotypic differences between both types of HX, KCNN4-HX has been proposed to be termed Gardos channelopathy, an independent disease.3,11

Results from a previous study indicated enhanced glycolytic rate and altered RBC energy levels in PIEZO1-HX.19 This metabolic alteration likely results from increased cellular demand for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to fuel the sodium pump (ATP1) and the plasma membrane calcium pump (PMCA), which maintain proper RBC volume and deformability.19,20 ATP production in RBC fully depends on glycolysis, and a key regulatory enzyme in this pathway is pyruvate kinase (PK). We previously reported on decreased PK activity and thermostability as a novel pathophysiological feature in various forms of hereditary hemolytic anemia such as thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD).21-23 To date, there is limited evidence on whether HX RBCs also display altered PK properties and metabolic disturbances.19-21 This is of particular importance in light of the emerging PK activator therapy. Small-molecule allosteric activators of PK, such as mitapivat, etavopivat, and tebapivat, have been demonstrated to have beneficial effects in both preclinical and clinical studies in a range of rare anemias (eg, hereditary PK deficiency [PKD], SCD, thalassemia, and hereditary spherocytosis [HS]).21,24-30 Considering the increased metabolic demand in HX RBCs, activation of PK could possibly support this demand by enhancing cellular metabolism.

In this study, we investigated energy metabolism in HX RBCs and the effect of ex vivo PK activation on RBC properties. We show characteristic differences between PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX RBCs as well as both compared to healthy control (HC) RBCs. Furthermore, in both PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX, PK can be activated, subsequently increasing ATP levels. Notably, we observed that KCNN4-HX RBCs show increases in parameters related to hydration status upon ex vivo PK activation, which does not occur in most treated PIEZO1-HX RBCs. This result suggests that patients with KCNN4-HX and those with PIEZO1-HX may respond differently to PK activation treatment.

Methods

Patients

Patients (aged ≥16 years) diagnosed with either PIEZO1-HX or KCNN4-HX were included. All genetic variants were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.31 Blood samples were collected in either EDTA (for untreated whole blood or RBCs) or lithium-heparin (for ex vivo treated RBCs). The studies were approved by the medical ethical research board of the University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands (17/450M and 21/793) and were conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Blood from 10 HCs was obtained via the institutional blood donor service (18/774).

Additional methods describing the methods for PKLR gene analysis and digital microscopy as well as for assessing hemoglobin-oxygen affinity and intracellular calcium levels can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Osmotic gradient ektacytometry

Osmotic gradient ektacytometry measurements of RBCs of the HCs and patients with HX were obtained using the osmoscan module on the Laser Optical Rotational Red Cell Analyzer (Lorrca; RR Mechatronics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as described elsewhere.14,32 Briefly, whole blood or treated RBCs were standardized to a fixed RBC count of 1000 × 106/L and mixed with 5 mL of Elon ISO (RR Mechatronics). Subsequently, RBCs were exposed to a constant shear stress (30 Pa) and an osmolarity gradient from ∼60 mOsm/kg to 600 mOsm/kg. Deformation is then calculated from changes in the diffraction pattern by means of a laser beam and is expressed as the elongation index (EI). Outcome parameters include the Omin (reflecting RBC surface area-to-volume ratio), EImax (reflecting total RBC surface area and maximal deformability of RBCs), Ohyper (reflecting RBC hydration), and area under the curve (AUC; calculated from the Omin to the hyperosmolar region [500 mOsm/kg]).

RBC PK activity and thermostability

RBCs were purified from whole blood with the use of a cellulose column according to standardized methods.33 Subsequently, PK and hexokinase (HK) activity was measured in the lysates of the purified RBCs as previously described.33 The PK thermostability test was performed on the same RBC lysates and involved PK activity measurement after 0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 60 minutes of incubation at 53°C (outcome after 60 minutes is shown in results).34 PK activity and thermostability were measured at a phosphoenolpyruvate concentration of 5 mM in untreated RBCs and at 0.5 mM for RBCs treated ex vivo with tebapivat (as described in the section “Ex vivo treatment with the PK activator tebapivat”). The latter condition allows for a better evaluation of the effect of allosteric activation of PK. The measurement of red blood cell PK protein levels is described in the supplemental Methods.

Targeted metabolomics

Quantitative analysis of ATP and 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) was performed as described previously.35 Metabolites were analyzed by high-resolution accurate mass detection on a Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peak identification and integration were conducted with Maven software.36

Untargeted metabolomics on dried blood spots

Sample preparation from dried blood spots, direct-infusion high-resolution mass spectrometry, and data processing was performed as previously reported.37,38 Mass peak intensities were defined using a peak-calling bioinformatics pipeline developed in R programming software (http://github.com/UMCUGenetics/DIMS). Because direct-infusion high-resolution mass spectrometry is unable to separate isomers, mass peak intensities consisted of summed intensities of these isomers. Metabolite annotation was based on the human metabolome database (version 3.6). This resulted in 1895 unique metabolite annotations.

Ex vivo treatment with the PK activator tebapivat

Purified RBCs were diluted to a concentration of 0.08 × 1012 to 0.1 × 1012 RBCs per liter in AGAM buffer (containing 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline [Sigma-Aldrich], 1.2 mM adenine [Sigma-Aldrich], 30 mM d-mannitol (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% d-(+)-glucose solution [Sigma-Aldrich], pH 7.40 at room temperature). RBCs were then treated with either 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich) as a vehicle control or with 2 μM tebapivat (also known as AG-946; Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc) for 16 hours at 37°C, with tumbling. After ex vivo treatment, enzyme activities were measured. For other assays (ie, osmotic gradient ektacytometry, hemoglobin-oxygen affinity, and intracellular calcium), RBCs were first concentrated to ±3.6 × 1012 RBCs per liter To assess the effect on PK thermostability, RBC lysates were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide or tebapivat (1 μM for PIEZO1-HX and 500 nM for KCNN4-HX) for 2 hours at 37°C before incubation at 53°C.

Data analysis

No further data filtering was applied. Multivariate principal component analysis, in which the number of features is reduced by combining them into fewer explanatory variables, was used to explore the variation in metabolic fingerprints between patients and controls. Analysis of variance with post hoc Fisher least significant difference was used to identify statistically significant differences in the metabolites between HCs and the 2 patient groups. Considering that 1895 metabolites were included in the analysis, we also reported the false discovery rate–adjusted P value.

Results

Patient characteristics

Samples from 12 patients with PIEZO1-HX (median age, 30 years [range, 17-75]; 6/12 female), 3 patients with KCNN4-HX (median age, 39 years [range, 20-55]; 1/3 female), and 10 HCs (median age, 50 years [range, 26-67]; 7/10 female) were collected. Six different PIEZO1 pathogenic gain-of-function mutations were identified (Table 1). Two patients (16.7%) with a PIEZO1 mutation were splenectomized, and 6 patients (50%) are regularly phlebotomized. None had been treated with iron chelators. Perinatal edema was not reported in any of the patients. None of the patients with a KCNN4 mutation had a splenectomy or had been treated with phlebotomy or iron chelators. Hereditary deficiency of PK was excluded in all patients by DNA sequence analysis of the PKLR gene.

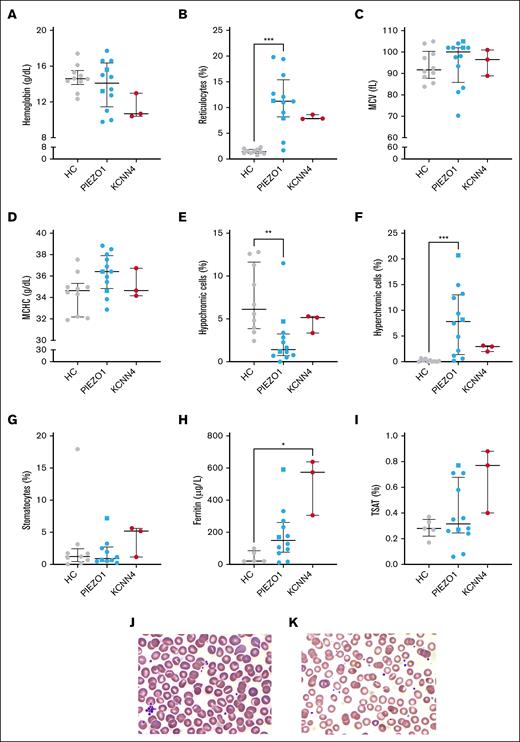

RBCs are denser in PIEZO1-HX than in KCNN4-HX

Routine hematologic values showed that hemoglobin values of the patients did not significantly differ from those of the HCs, even though there were anemic patients in both groups (Figure 1A). There was a considerable degree of reticulocytosis in both types of HX (Figure 1B), including patients with PIEZO1-HX who did not have anemia. Mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) did not differ between HCs and the patients in both HX groups (Figure 1C-D), and the slight tendency toward an increase in mean corpuscular volume may be related to the reticulocytosis. The percentages of hypochromic and hyperchromic cells decreased and increased, respectively, in PIEZO1-HX (Figure 1E-F). MCHC and the percentage of hyperchromic cells did not correlate either (supplemental Figure 1A). Although there is a higher percentage of denser cells, the mean overall density of the RBC population appears to be within the normal range in PIEZO1-HX. In KCNN4-HX, the percentage of hypochromic cells was similar to that in HCs, whereas the percentage hyperchromic cells were slightly higher in all 3 patients. In line with previous reports,11 stomatocytes were found in low numbers on peripheral blood smears of all 3 groups (Figure 1G). Overall, no evident differences were observed between untreated, splenectomized, and phlebotomized patients. However, ferritin levels and transferrin saturation varied greatly in patients with PIEZO1-HX, and interestingly, they were still elevated in some phlebotomized patients (Figure 1H-I). Iron parameters were evidently elevated in 2 patients with KCNN4-HX. Representative peripheral blood smears from whole blood are shown in Figure 1J (PIEZO1-HX) and Figure 1K (KCNN4-HX), showing few stomatocytes.

Routine hematologic parameters, ferritin levels, and stomatocyte counts of patients with HX with a PIEZO1 or KCNN4 mutation. (A-D) Various routine hematologic parameters were measured in HCs and patients with PIEZO1- and KCNN4-HX, including hemoglobin level (A), reticulocyte count (B), MCV (C), and MCHC (D). (E-F) Considering that dehydration is characteristic of HX, hypochromic cells (E) and hyperchromic cells (F) were measured. (G) The percentage of stomatocytes (PIEZO1, n = 10) was evaluated. (H-I) In addition, ferritin levels (H) and TSAT percentages (I) were compared between groups (HCs, n = 5). (J-K) Representative peripheral blood smears from PIEZO1-HX whole blood (J) and KCNN4-HX whole blood (K) are shown. Error bars represent median with IQR. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients. MCV, mean corpuscular volume; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Routine hematologic parameters, ferritin levels, and stomatocyte counts of patients with HX with a PIEZO1 or KCNN4 mutation. (A-D) Various routine hematologic parameters were measured in HCs and patients with PIEZO1- and KCNN4-HX, including hemoglobin level (A), reticulocyte count (B), MCV (C), and MCHC (D). (E-F) Considering that dehydration is characteristic of HX, hypochromic cells (E) and hyperchromic cells (F) were measured. (G) The percentage of stomatocytes (PIEZO1, n = 10) was evaluated. (H-I) In addition, ferritin levels (H) and TSAT percentages (I) were compared between groups (HCs, n = 5). (J-K) Representative peripheral blood smears from PIEZO1-HX whole blood (J) and KCNN4-HX whole blood (K) are shown. Error bars represent median with IQR. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients. MCV, mean corpuscular volume; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

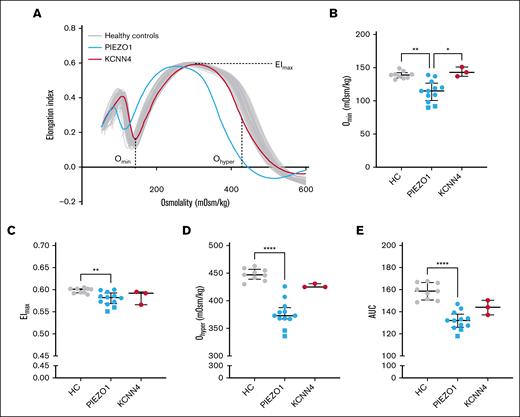

RBCs from patients with HX with PIEZO1 variants are more dehydrated and have an increased surface area-to-volume ratio compared to those from patients with KCNN4 variants

Osmotic gradient ektacytometry measurements showed the typical left shift of the curve in patients with PIEZO1-HX, whereas this finding was absent in patients with KCNN4-HX (Figure 2A). In particular, the surface area-to-volume ratio (Omin) of PIEZO1-HX RBCs was substantially higher, as reflected by a lower Omin in PIEZO1-HX, compared to KCNN4-HX and HC RBCs (Figure 2B). This result could implicate that osmotic fragility is decreased in PIEZO1-HX RBCs. The EImax, representing total membrane surface area, was slightly decreased in PIEZO1-HX (median [IQR], 0.582 [0.569-0.593] vs 0.601 [0.593-0.602] in HC; P < .01; Figure 2C). Ohyper was strongly decreased in PIEZO1-HX (373 [367-388] mOsm/kg) compared to HC (447 [439-457] mOsm/kg; P < .0001), whereas KCNN4-HX RBCs showed Ohyper values within the lower end of the normal range (425 [425-431] mOsm/kg; Figure 2D). Ohyper values did correlate with the percentage of hyperchromic cells, but not with MCHC (supplemental Figure 1B-C). In line with these findings, PIEZO1-HX RBCs also showed a decreased AUC (Figure 2E). Here, the 2 splenectomized patients were found to have the lowest values in all osmotic gradient ektacytometry outcome parameters, suggesting that PIEZO1-HX RBCs are less deformable and more dehydrated after splenectomy.

RBC deformability measured by osmotic gradient ektacytometry in HX. (A) Representative osmotic gradient ektacytometry curve of a patient with PIEZO1-HX (blue) and a patient with KCNN4-HX (red). (B) Median values of Omin, representing surface area-to-volume ratio, of 12 patients with PIEZO1-HX, 3 patients with KCNN4-HX, and 9 HCs. (C) Median values of EImax, representing the total surface area and maximal deformability of the RBC population. (D) Median values of Ohyper, representing the hydration of RBCs. (E) Median values of AUC. Error bars represent IQR. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

RBC deformability measured by osmotic gradient ektacytometry in HX. (A) Representative osmotic gradient ektacytometry curve of a patient with PIEZO1-HX (blue) and a patient with KCNN4-HX (red). (B) Median values of Omin, representing surface area-to-volume ratio, of 12 patients with PIEZO1-HX, 3 patients with KCNN4-HX, and 9 HCs. (C) Median values of EImax, representing the total surface area and maximal deformability of the RBC population. (D) Median values of Ohyper, representing the hydration of RBCs. (E) Median values of AUC. Error bars represent IQR. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

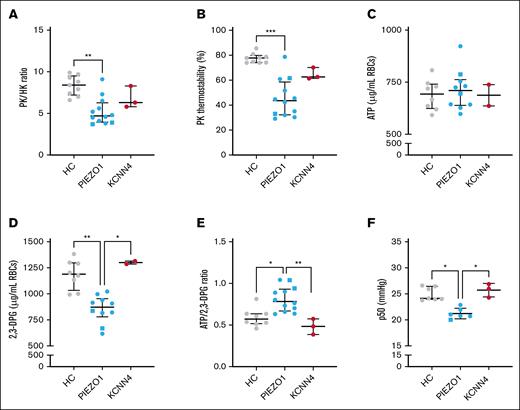

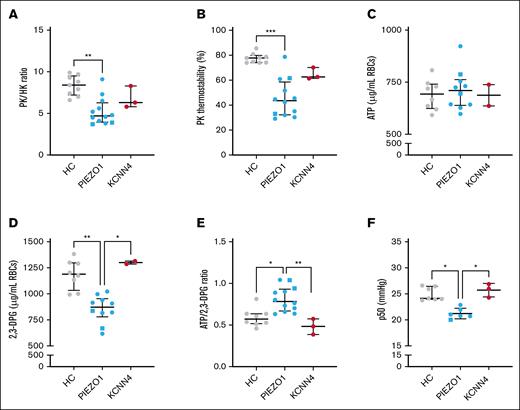

PK properties and ATP:2,3-DPG ratio are altered in PIEZO1-HX RBCs

Next, we next whether PK properties in HX RBCs were affected, similar to other forms of hereditary hemolytic anemias. PK activity was within the normal range (supplemental Figure 2A), but compared to the activity of HK, another enzyme whose activity is age-dependent, the activity was decreased as reflected by a significantly decreased PK:HK ratio (median [IQR], 4.7 [4.0-6.3] compared to 8.4 [7.2-9.5] for HCs; P = .001; Figure 3A). The PK:HK ratio in the patients with KCNN4-HX (6.3 [5.8-8.3]) did not differ significantly from the HCs, although patients 13 and 14 showed lower PK:HK ratios than the HCs. The relative deficiency of PK in PIEZO1-HX was accompanied by a substantial decrease in PK thermostability (PK thermostability after 60 minutes, 43.6% [32.3-58.6%] compared to 77.8% [74.1-79.9%] in HCs; P < .0001), which was also observed in KCNN4-HX RBCs, albeit to a lesser extent (62.6% [61.4-70.2%], not significant; all 3 patients had lower PK thermostability than the HCs; Figure 3B). The decrease in PK:HK ratio and PK thermostability in PIEZO1-HX RBCs was accompanied by lower red blood cell PK protein levels compared to HC and KCNN4-HX RBCs (supplemental Figure 2B).

Properties of PK and related metabolic features in HX RBCs. (A-C) Properties of PK were assessed in HCs and patients with HX (both in PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX). (A) The relative PK activity compared to the HK activity (expressed as the PK:HK ratio) was determined. (B) The PK thermostability after 60 minutes of incubation was determined. (C-E) ATP and 2,3-DPG and their ratio. (F) Given that 2,3-DPG plays a central role in hemoglobin-oxygen affinity, the p50 was measured in the 3 groups (n = 6 for PIEZO1-HX). Error bars represent IQR. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

Properties of PK and related metabolic features in HX RBCs. (A-C) Properties of PK were assessed in HCs and patients with HX (both in PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX). (A) The relative PK activity compared to the HK activity (expressed as the PK:HK ratio) was determined. (B) The PK thermostability after 60 minutes of incubation was determined. (C-E) ATP and 2,3-DPG and their ratio. (F) Given that 2,3-DPG plays a central role in hemoglobin-oxygen affinity, the p50 was measured in the 3 groups (n = 6 for PIEZO1-HX). Error bars represent IQR. ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

To explore whether altered PK properties had an effect on RBC metabolism, particularly on the key glycolytic intermediates ATP and 2,3-DPG, we performed quantitative analysis of RBC ATP and 2,3-DPG levels. ATP levels were similar in both HX subtypes and HCs (Figure 3C). However, 2,3-DPG levels were significantly lower in patients with PIEZO1-HX (n = 10), whereas in KCNN4-HX, 2,3-DPG levels were within the upper range of the HCs (n = 2; Figure 3D). Consequently, the ATP:2,3-DPG ratio was increased in PIEZO1-HX RBCs (0.783 [0.670-0.931]) compared to KCNN4-HX RBCs (0.484 [0.386-0.574]; P < .01) and HC RBCs (0.572 [0.517-0.636]; P < .05; Figure 3E). In line with the decreased 2,3-DPG levels, PIEZO1-HX RBCs also showed a decrease in p50, reflecting an increase in hemoglobin-oxygen affinity (Figure 3F).

Exact P values for the results described above can be found in supplemental Table 1.

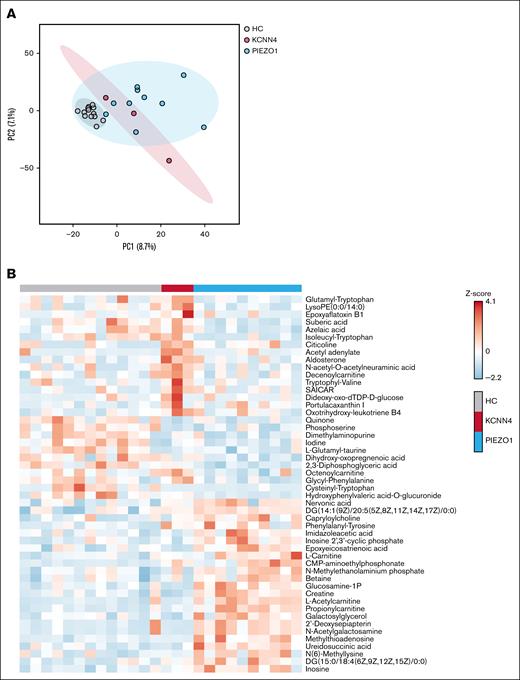

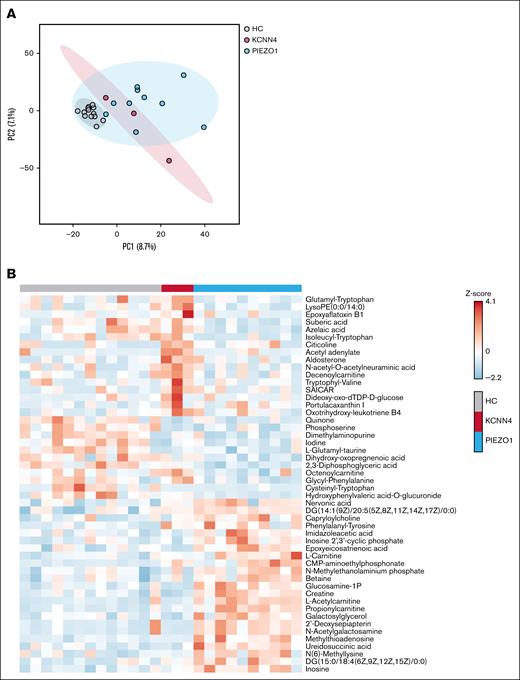

Untargeted metabolomics demonstrates distinct metabolic profiles in RBCs from patients with PIEZO1-HX and those with KCNN4-HX

Prompted by the observed metabolic alterations, we next performed untargeted metabolomics on whole blood. Broad data exploration by the dimension-reducing principal component analysis demonstrated the natural separation of patient groups from HCs by metabolites captured in principle component 1 (Figure 4A). Remarkably, there was also a certain separation between PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX. Although the numbers are low, particularly in the KCNN4-HX group, our data suggest that patients with PIEZO1-HX and those with KCNN4-HX have distinct metabolic profiles. When comparing the 3 groups, 9 metabolites had a false discovery rate–adjusted P value of <.05 and 157 metabolites had a raw P value of <.05 (supplemental File 1). Hierarchical clustering of the top 50 most significantly different metabolites (lowest P value) highlighted distinct clusters of metabolites that are increased in KCNN4-HX but not in PIEZO1-HX and vice versa or that are decreased in both groups compared to HCs (Figure 4B). These results confirmed the decreased 2,3-DPG levels in PIEZO1-HX and demonstrated increases in free l-carnitine, l-acetylcarnitine, and propionylcarnitine in PIEZO1-HX compared to HCs and KCNN4-HX.

Explorative untargeted metabolomics. (A) PCA of HX and HCs, divided per subgroup of PIEZO1-HX (n = 10) and KCNN4-HX (n = 3) displayed with 95% confidence interval. (B) Heat map demonstrating the top 50 most distinctive metabolites among the HCs and patients with PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX. PC, principal component.

Explorative untargeted metabolomics. (A) PCA of HX and HCs, divided per subgroup of PIEZO1-HX (n = 10) and KCNN4-HX (n = 3) displayed with 95% confidence interval. (B) Heat map demonstrating the top 50 most distinctive metabolites among the HCs and patients with PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX. PC, principal component.

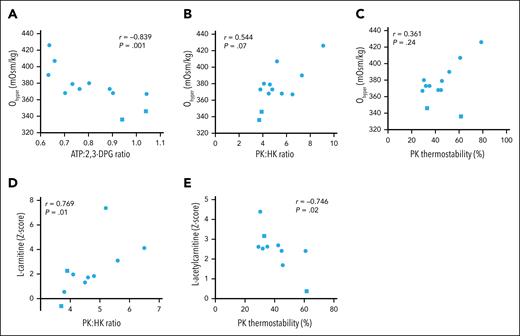

Correlation between metabolic features and RBC dehydration in patients with PIEZO1-HX

To explore whether the RBC dehydration observed in PIEZO1-HX is related to metabolic features, in particular PK function, we performed a correlation analysis for the 12 patients with PIEZO1-HX. We found that the percentage of hyperchromic cells correlated strongly to Ohyper values (r = –0.867; P < .001), whereas no correlation was found between MCHC or the percentage of hypochromic cells and Ohyper values. A decrease in Ohyper value was found to be associated with an increase in ATP:2,3-DPG ratio (r = –0.839; P = .001; Figure 5A). The Ohyper value also tended to correlate with the PK:HK ratio (r = 0.544; P = .07; Figure 5B) but not with PK thermostability (r = 0.361; P = .24; Figure 5C). We found that l-carnitine and l-acetylcarnitine correlated with PK:HK ratio and PK thermostability, respectively (Figure 5D-E), but not with markers of dehydration, except for MCHC, which correlated with l-acetylcarnitine (r = –0.742; P < .05). Overall, these findings suggest a link between dehydration and altered RBC metabolism in PIEZO1-HX.

Biomarkers of RBC hydration correlate with metabolites in PIEZO1-HX. (A-C) Correlations between Ohyper, the main biomarker to represent RBC hydration, and ATP:2,3-DPG ratio (A), PK:HK ratio (B), and PK thermostability (C). (D) Correlation between l-carnitine and PK:HK ratio. (E) Correlation between l-acetylcarnitine and PK thermostability. Phosphoenolpyruvate concentration of 5 mM for both PK:HK ratio and PK thermostability. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

Biomarkers of RBC hydration correlate with metabolites in PIEZO1-HX. (A-C) Correlations between Ohyper, the main biomarker to represent RBC hydration, and ATP:2,3-DPG ratio (A), PK:HK ratio (B), and PK thermostability (C). (D) Correlation between l-carnitine and PK:HK ratio. (E) Correlation between l-acetylcarnitine and PK thermostability. Phosphoenolpyruvate concentration of 5 mM for both PK:HK ratio and PK thermostability. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

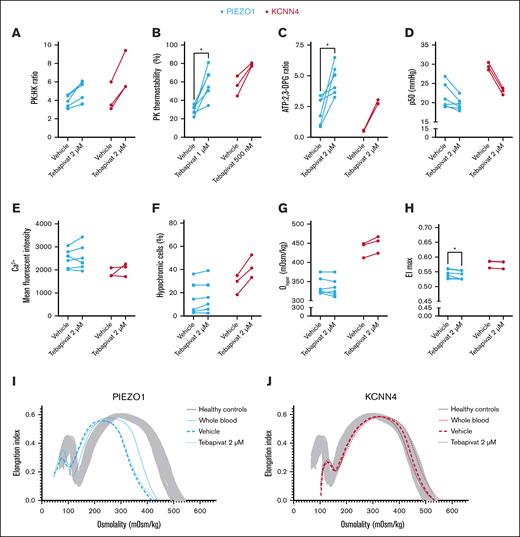

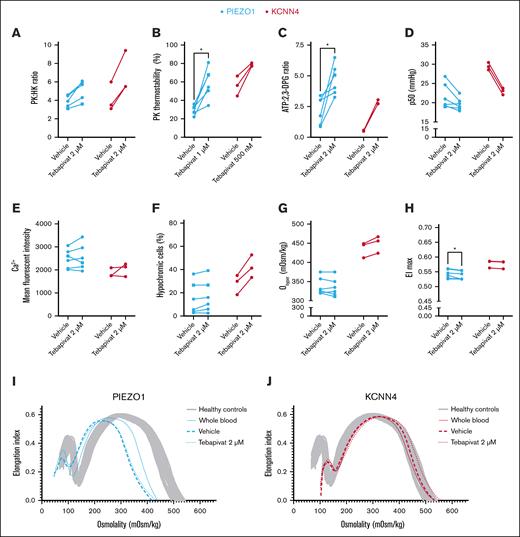

Ex vivo tebapivat treatment of RBCs from patients with HX enhances energy metabolism and affects various RBC properties, predominantly in KCNN4-HX

The relative decrease in PK activity, altered RBC metabolism, and its relation to dehydration prompted us to investigate how HX RBCs would respond to ex vivo treatment with tebapivat, a novel allosteric activator of PK. We treated RBCs from 6 patients with PIEZO1-HX and 3 with KCNN4-HX ex vivo and observed an increase in PK activity, resulting in an increased PK:HK ratio (PIEZO1-HX, median [IQR] PK:HK ratio of 5.7 [4.0-6.0] for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 3.9 [3.3-4.6] for vehicle; P = .06; KCNN4-HX, 5.5 [5.5-9.4] for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 3.5 [3.1-6.0] for vehicle; P = .25; Figure 6A). This was accompanied by an improvement in PK thermostability (Figure 6B). ATP levels increased in all patients, whereas 2,3-DPG levels decreased, except for the 3 patients with PIEZO1-HX that had the lowest starting values of 2,3-DPG (patients 1, 5, and 11; supplemental Figure 3A-B). Hence, the overall ATP:2,3-DPG ratio increased (PIEZO1-HX [ATP:2,3-DPG ratio of 4.55 (3.54-5.77) for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 2.39 (0.96-3.12) for vehicle; P = .03]; KCNN4-HX [2.74 (2.73-3.05) for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 0.53 (0.49-0.58) for vehicle; P = .25]; Figure 6C). This was accompanied by a decrease in p50, except for the same 3 patients with PIEZO-HX with low starting values of 2,3-DPG, for which the p50 remained unchanged (Figure 6D). Ex vivo treatment with tebapivat did not affect intracellular calcium levels in both types of HX (Figure 6E). Interestingly, RBCs from all (3/3) patients with KCNN4-HX showed increased Ohyper values (456 [424-467] mOsm/kg for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 446 [412-449] mOsm/kg for vehicle; P = .25) and increases in hypochromic RBCs (Figure 6F-G), suggesting changes in RBC hydration. Simultaneously, this was only observed in RBCs from 2 of 6 patients with PIEZO1-HX. No effect on MCHC and the percentages of hyperchromic or dense cells were observed for both PIEZO1- and KCNN4-HX RBCs (supplemental Figure 4). In various patients, EImax values decreased only minimally, but they were significantly decreased in PIEZO1-HX (0.535 [0.525-0.554] for 2 μM of tebapivat vs 0.542 [0.528-0.560] for vehicle; P = .03; Figure 6H). Representative osmotic gradient ektacytometry curves of a patient with PIEZO1-HX and one with KCNN4-HX are depicted in Figure 6I-J, respectively.

Effects of ex vivo PK activation treatment on HX RBCs. (A) RBCs of patients with HX (PIEZO1-HX, n = 6; KCNN4-HX, n = 2) were treated ex vivo with the PK activator tebapivat (2 μM) overnight, which led to an increase in PK activity as reflected by the PK:HK ratio. (B) PK thermostability showed improvements upon ex vivo treatment with tebapivat. PK thermostability after 60 minutes incubation is reported. (C-D) The effect of increased PK activity on ATP:2,3-DPG ratio and hemoglobin-oxygen affinity. (E) Effect of PK activation on intracellular calcium levels. (F-G) To determine the effect of enhanced glycolysis on RBC hydration, both the percentage of hypochromic cells (F) and the Ohyper values (G) were evaluated. (H) Along with the effect on Ohyper, the effect on EImax was also determined. (I-J) Individual representative osmotic gradient ektacytometry curves of PIEZO1-HX (I) and KCNN4-HX (J) show that no improvement in hydration is observed in patients with PIEZO1, whereas patients with KCNN4-HX show improved Ohyper values. ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

Effects of ex vivo PK activation treatment on HX RBCs. (A) RBCs of patients with HX (PIEZO1-HX, n = 6; KCNN4-HX, n = 2) were treated ex vivo with the PK activator tebapivat (2 μM) overnight, which led to an increase in PK activity as reflected by the PK:HK ratio. (B) PK thermostability showed improvements upon ex vivo treatment with tebapivat. PK thermostability after 60 minutes incubation is reported. (C-D) The effect of increased PK activity on ATP:2,3-DPG ratio and hemoglobin-oxygen affinity. (E) Effect of PK activation on intracellular calcium levels. (F-G) To determine the effect of enhanced glycolysis on RBC hydration, both the percentage of hypochromic cells (F) and the Ohyper values (G) were evaluated. (H) Along with the effect on Ohyper, the effect on EImax was also determined. (I-J) Individual representative osmotic gradient ektacytometry curves of PIEZO1-HX (I) and KCNN4-HX (J) show that no improvement in hydration is observed in patients with PIEZO1, whereas patients with KCNN4-HX show improved Ohyper values. ∗P < .05. Square symbols indicate splenectomized patients.

Discussion

In this study, we present a detailed functional and metabolic analysis of RBCs from patients with PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX. Our results indicate that altered RBC glycolysis, including compromised PK function, contributes to the pathophysiology of PIEZO1-HX. This likely affects ATP yield and other properties of the RBC, in particular hydration. Interestingly, in contrast to PIEZO1-HX, RBCs from patients with KCNN4-HX have less compromised PK function, which further emphasizes the differences in pathophysiology between both these disorders. Moreover, we are the first to demonstrate that PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX also responded differently to ex vivo treatment with the novel PK activator tebapivat. Specifically, KCNN4-HX RBCs showed changes in parameters suggesting improved hydration, which is intriguing because the RBC hydration status of these patients does not seem to be compromised. Interestingly, in most patients with PIEZO1-HX, the increase in ATP levels did not improve hydration. This result indicates that enhanced energy levels by themselves were not sufficient to negate dehydration in PIEZO1-HX RBCs.

The relationship between dehydration and PK properties in PIEZO1-HX RBCs, along with the relative PK deficiency (in both HX variants) provided a rationale to study the effects of PK activation. Despite improvements in PK activity and ATP levels, no response was observed in RBC hydration, deformability, or density in most patients with PIEZO1-HX. The 2 patients with PIEZO1-HX that exhibited increases in Ohyper were related and had the p.Arg2456His variant. This missense variant has been described extensively before, in which it has been reported to lead to a higher inactivation time of Piezo1 compared to other variants.1,2,8,11,39-41 Whether there is a relation between the position of the variant in the protein and the response to PK activation remains to be explored. Interestingly, the RBCs of all 3 KCNN4 patients did show changes in parameters related to RBC hydration and density after ex vivo treatment. This outcome illustrates that the increase in ATP likely affects hydration homeostasis in KCNN4-HX RBCs, possibly due to ATP-dependent changes ion homeostasis. Although KCNN4-HX RBCs are not dehydrated, these observed functional changes could indicate that PK activation may increase the RBC life span in vivo (due to overall increases in RBC hydration and thus, the possible prevention of RBC clearance). However, in vivo studies should confirm this hypothesis.

Although it may not be surprising that these 2 separate disorders differ in terms of metabolism, it remains interesting how 2 channelopathies exhibit such distinguished metabolic characteristics. PK thermostability was more prominently affected in PIEZO1-HX, which may be related to the increased intracellular calcium levels or increased levels of oxidative stress.42,43 Interestingly, although a decrease in ATP and increase in 2,3-DPG can be observed in PKD,44-46 our results show that the decrease in PK activity is accompanied by decreased levels of 2,3-DPG in PIEZO1-HX RBCs. Interestingly, 2,3-DPG levels are essentially unaffected in KCNN4-HX RBCs. Notably, others have reported signs of enhanced glycolysis in PIEZO1-HX.19,47 Besides the decreased levels of 2,3-DPG in PIEZO1-HX,19,48 various other glycolytic intermediates were decreased, and recent studies using glucose tracing showed an increased turnover of glycolytic metabolites.47 It was proposed that PIEZO1-HX RBCs have increased ATP requirement to fuel the membrane pumps, leading to an increased glycolytic rate.

Kiger et al proposed that elevated calcium levels in PIEZO1-HX might increase the activity of phosphofructokinase, another rate-limiting glycolytic enzyme, thus enhancing glycolysis via this route.49,50 Furthermore, in macrophages, glycolysis is favored upon Piezo1 activation via hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α).51 HIF1α is known to regulate metabolism in hematopoietic stem cells and directs early erythroblasts toward glycolysis.52,53 The gain-of-function of Piezo1 in HX might enhance glycolysis via HIF1α expression during erythropoiesis, where Piezo1 plays a role in erythroid differentiation.54-57 Finally, in mature RBCs, the activation of Piezo1 leads to the shear-induced release of ATP, which then facilitates local vasodilatation by inducing nitric oxide synthesis by endothelial cells.58,59 Possibly, the continuous activation of Piezo1 depletes the intracellular ATP pools, with a consequential compensatory increase in glycolytic flux. It is important to identify the exact mechanism behind this disturbed metabolism to better understand the highly variable phenotype of PIEZO1-HX, where patients may present with erythrocytosis and can have a marked reticulocytosis despite mild or no anemia.56,60,61 Moreover, none of the mechanisms described above provide a full explanation as to why PK properties are affected when overall glycolysis is enhanced.

Our untargeted metabolomic analysis showed distinct profiles for both PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX. Interestingly, free l-carnitine and the short-chain carnitines l-acetylcarnitine and propionylcarnitine were elevated in PIEZO1-HX, similar to that in PKD and HS,37,62,63 but not in KCNN4-HX. Given that (acyl)carnitines counteract membrane lipid peroxidation in RBCs,64,65 this may be indicative for lesser lipid peroxidation in KCNN4-HX. Moreover, in contrast to that in PKD and SCD, no changes in polyamines were observed in both PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX.37,66 Polyamines provide membrane stabilization,67 which would also be expected to be of importance in PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX RBCs. The correlation between carnitines and PK properties in PIEZO1-HX is peculiar, as both are linked to oxidative damage,65,68 and would be of interest for future research.

PIEZO1-HX RBCs could potentially benefit from increased ATP levels via the activation of the ATP-dependent PMCA1 pump. The activation of this pump could possibly negate the increased influx of calcium, thus preventing the activation of the Gardos channel. Recently, Le et al demonstrated an increased calcium efflux in SCD RBCs upon ex vivo treatment with the PK activator mitapivat.69 In our ex vivo setting, we did not find changes in intracellular calcium levels upon PK activation. This could explain why no or little changes in hydration are observed. Considering that calcium levels may change rapidly,70 a detailed study on PMCA1 function would be of additional value. The increased levels of calcium in PIEZO1-HX RBCs may also play a role in the different response to PK activation compared to that of KCNN4-HX RBCs.

Currently, a phase 2 clinical trial with mitapivat is conducted, which includes patients with HX (SATISFY trial).71 Previously, mitapivat treatment was shown to improve hemoglobin values in patients with PKD, SCD, and thalassemia and ameliorated anemia in mice with HS.21,24-30 How patients with HX respond to mitapivat will be of much interest because current treatment options for both forms of HX are limited. Notably, a clinically relevant concern could be that the activation of PK may further increase hemoglobin-oxygen affinity in PIEZO1-HX, subsequentially decreasing oxygen delivery to the tissues. However, our ex vivo data demonstrate that the effect on hemoglobin-oxygen affinity is limited, specifically in patients with increased hemoglobin-oxygen affinity at baseline.

A limitation of the current study is the small sample size, and these results should thus be weighed carefully. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the patients with PIEZO1-HX group with regard to genetic variants and therapy (splenectomy and phlebotomies). Simultaneously, it is also a strength that the analysis in this study was not limited to only 1 family or mutation.

Overall, we provide novel insights in RBCs from both patients with PIEZO1-HX and those with KCNN4-HX, in particular with regard to metabolic properties. Our results also allow new questions to emerge concerning the mechanisms behind altered glycolysis. Importantly, we demonstrate that ex vivo PK activation affects PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX RBCs differently: in PIEZO1-HX, hydration did not improve evidently, whereas in KCNN4-HX, parameters related to hydration (Ohyper and hypochromic cells) increased despite no initial dehydration being present. Our findings strengthen the concept that PIEZO1-HX and KCNN4-HX should be considered as different disorders, termed as Piezo1 channelopathy and Gardos channelopathy, respectively. Future ex vivo and clinical studies are essential in order to determine whether there may be a role for PK activation treatment for these 2 distinct RBC disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study. The authors also thank Penelope Kosinski, Lenny Dang, and Charles Kung (Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Boston, MA) for their aid in the measurement of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate and adenosine triphosphate; Annet van Dijk-van Wesel (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands) for her aid in the DNA analysis of the PKLR gene; and Jürgen Riedl (Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht, The Netherlands) for his aid in digital microscopy.

This study was supported, in part, by research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals (J.R.A.d.W., J.E.-B., E.J.v.B., M.R., and R.v.W).

Authorship

Contribution: E.J.v.B., M.A.E.R., and R.v.W. designed and supervised the study. J.R.A.d.W and M.A.E.R. coordinated the study and performed the experiments and analyses. T.J.J.R., B.v.D., and J.J.M.J. were involved in the metabolomics experiments. J.E.-B., B.A.v.O., and S.v.S. aided in the ektacytometry and enzyme experiments. J.R.A.d.W., T.D., S.v.S., M.B., E.J.v.B., M.A.E.R., and R.v.W. recruited participants and collected patient data. J.R.A.d.W., T.J.J.R., M.A.E.R., and R.v.W. wrote the original draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.A.d.W. and J.E.-B., have received research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc. A.G. receives research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Bristol Myers Squibb, Saniona, and Sanofi; and has served as a consultant for Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Pharmacosmos, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. M.W.-R. is currently an employee and shareholder of Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc. E.J.v.B, has served as consultant for, and received funding from, Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc. M.A.E.R. has received research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Axcella Health, and RR Mechatronics; and has served as consultant for Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc. R.v.W has served as a consultant for Pfizer and Agios Pharmaceuticals; and has received research funding from Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Axcella Health, and RR Mechatronics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Richard van Wijk, Central Diagnostic Laboratory Research, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 100, 3584 CX Utrecht, The Netherlands; email: r.vanwijk@umcutrecht.nl.

References

Author notes

M.A.E.R. and R.v.W. contributed equally to this study.

Data and protocols are available from the corresponding author, Richard van Wijk (r.vanwijk@umcutrecht), upon request. Data will be shared in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation and European Union privacy laws.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.