Key Points

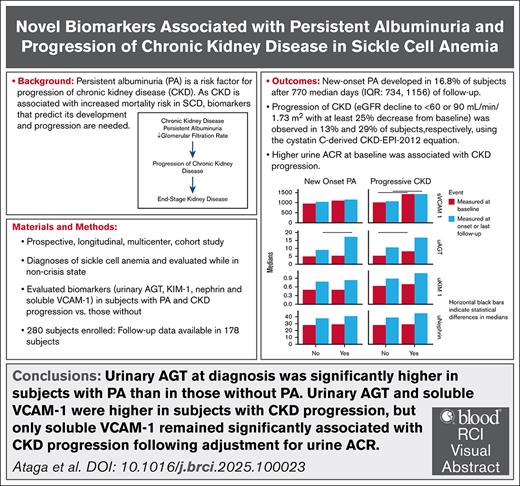

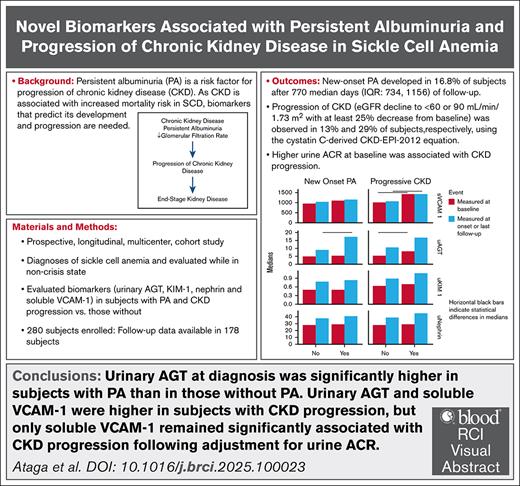

There are no biomarkers that predict the development of persistent albuminuria in individuals with sickle cell anemia.

Urinary AGT and soluble VCAM-1 may predict the development and progression of CKD in sickle cell anemia.

Visual Abstract

As chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with increased mortality in sickle cell disease (SCD), biomarkers that predict its development and progression are needed. We evaluated the association of select biomarkers with the development of persistent albuminuria (PA) and CKD progression in adults with SCD in a multicenter cohort. Of 178 patients with follow-up data, new-onset PA was observed in 16.8% and up to 29% developed CKD progression. In univariate analysis, patients with new-onset PA had higher white blood cell counts (10.1 × 109/L vs 8.4 × 109/L, P = .023) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (122.5 mm Hg vs 116 mm Hg, P = .022) at diagnosis than patients without PA. Patients with CKD progression had higher SBP (122 mm Hg vs 113 mm Hg, P = .001) and higher urine albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) (116.8 mg/g vs 17.95 mg/g, P = .006) at baseline. Patients with new-onset PA had higher urinary angiotensinogen (AGT) at diagnosis than those without PA (17.6 ng/mg [interquartile range (IQR), 13.5-32.1] vs 8.99 ng/mg [IQR, 6.7-16.1]; P = .02). Urinary AGT (8.03 ng/mg [IQR, 6.04-14.5] vs 5.5 ng/mg [IQR, 3.5-9.99]; P = .015) and plasma levels of soluble VCAM-1 (1434.5 ng/mL [IQR, 1160.5-1861.6] vs 1011.2 ng/mL [IQR, 833.5-1271.5]; P < .0001) at the baseline visit were higher in patients with CKD progression, but only soluble VCAM-1 remained significantly associated with CKD progression after adjustment for baseline urine ACR and estimated glomerular filtration rate. More studies are required to evaluate the predictive capacity of urinary AGT and soluble VCAM-1 for the development of PA and CKD progression in SCD. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT03277547.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited blood disorder that affects millions of individuals worldwide.1 It results in frequently debilitating complications, including chronic kidney disease (CKD). Persistent albuminuria (PA), an early clinical manifestation of CKD, is common in SCD2 and is a risk factor for progression of CKD.3,4 As CKD is associated with an increased risk of mortality in adults with SCD,5-8 identification of biomarkers that predict its development and progression is necessary. We have previously identified a significant and independent association between PA and urinary angiotensinogen (AGT), a biomarker of the renin-angiotensin system, in SCD.9,10

In this study, we have assessed the development of PA and the progression of CKD in a longitudinal cohort of patients with sickle cell anemia and evaluated the association of select research biomarkers (urinary AGT, urinary nephrin, urinary kidney injury molecule 1 [KIM-1], and plasma soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 [VCAM-1]) with PA development and CKD progression.

Methods

Study design and participants

The study design and participants in this prospective, longitudinal, multicenter, cohort study have been previously described.10,11 Briefly, patients seen for routine clinic visits who were eligible and agreed to participate were enrolled to evaluate the association of select biomarkers with PA and CKD progression. This study was designed to follow up patients every 12 months (±2 months) for up to 48 months. Patients were recruited at 4 sickle cell centers. Patients aged 18 to 65 years, with diagnoses of sickle cell anemia (homozygous sickle cell disease/sickle beta zero thalassemia), who had no pain episodes requiring medical contact during the preceding 4 weeks were evaluated while in their noncrisis “steady states.” A full list of the eligibility criteria is provided as the supplemental Data.

Biomarker and routine laboratory analyses

Plasma samples were prepared using a previously published method to minimize platelet activation.12 Plasma and urine samples were aliquoted, frozen immediately at −80°C, and batched for subsequent analysis. Plasma levels of cystatin C (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), soluble VCAM-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), KIM-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), urinary nephrin (LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA), and urinary AGT (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Gunma, Japan) were measured at baseline and yearly using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits according to manufacturers’ instructions. Urinary KIM-1, nephrin, and AGT concentrations were normalized to urine creatinine.

Complete blood counts, reticulocyte count, hemoglobin electrophoresis, chemistries including serum creatinine and liver function tests, urinalysis, and random spot urine for albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) were obtained at the baseline visit and yearly in the clinical laboratories of participating centers.

Definitions of study endpoints

PA was defined as urine ACR values ≥30 mg/g of creatinine obtained in ≥2 spot urine collections during the follow-up period or a single urine ACR value ≥100 mg/g, if only one assessment was available.3,11 In a multicenter cohort study of children and adults with SCD, 81% of patients with baseline urinary ACR values ≥100 mg/g had PA compared with 16% with baseline ACR of <100 mg/g.3 This finding was confirmed in another multicenter adult cohort which revealed that using ACR values of <100 and ≥100 mg/g, the probabilities of PA were 30.0% and 94.6%, respectively.11 Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the cystatin C–based Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI 2012) equation13 and the creatinine-based CKD-EPI 2021 equation.14 CKD progression was defined as a decline in estimated GFR (eGFR) to <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with a decrease by ≥25% from baseline using the cystatin C–based CKD-EPI 2012 or creatinine-based CKD-EPI 2021 equations.15,16 With the uncertainty regarding the appropriate eGFR cutoff for CKD in SCD, we also defined CKD progression as eGFR decline to <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with a decrease by ≥25% from baseline using both the cystatin C–based and creatinine-based equations.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized by medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages. Among patients with follow-up data, baseline characteristics were compared between those with PA and those without, using χ2 test (or Fisher exact test, if cell counts were small) and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests. Limited to patients without PA at baseline, we compared the characteristics between those who never developed PA and those who developed PA during the follow-up period at baseline and again at the last follow-up (if no PA) or at the time of diagnosis (if developed PA). We further modeled new-onset PA using logistic regression as a function of each baseline characteristic, adjusting for baseline urine ACR. Similarly, we compared characteristics between those with and without CKD progression using an eGFR cutoff of <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. As an exploratory analysis, we evaluated characteristics between those with and without CKD progression using an eGFR cutoff of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2. To further evaluate biomarkers and possible associations with PA (no development vs new-onset PA during the follow-up period), we calculated the change in biomarkers from baseline to last follow-up and compared PA status with Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests. We modeled urinary ACR (baseline through available follow-up values) as a function of time and respective urinary AGT follow-ups and the interaction between time and urinary AGT with a linear mixed model with a random intercept. As a type of sensitivity analysis, we repeated our analysis excluding those patients with baseline ACR ≥30 mg/g. Finally, we compared biomarkers (at baseline) by CKD progression status after adjusting for baseline urine ACR and eGFR using linear regression. As the normality assumption was often violated, we revealed the least-square means from these models but have statistically compared the residuals from this model (representing adjusted biomarkers) by CKD status with Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests. All analyses were 2 sided and conducted at a 0.05 significance level using R Studio (R version 4.4.2).17,18

Study approval

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of participating institutions. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Demographic and laboratory characteristics

Of 280 enrolled patients, follow-up data were available for 178 patients. For those with follow-up data, PA was present in 59 patients (33.1%) at study entry (baseline). Patients with baseline PA were significantly older (35 years [IQR, 27.5-43] vs 27 years [IQR, 23-36]; P = .001), had higher systolic blood pressure (SBP) (118 mm Hg [IQR, 108-133.5] vs 113 mm Hg [IQR, 108-121.5]; P = .04), and higher diastolic blood pressure (70 mm Hg [IQR, 65-77] vs 66 mm Hg [IQR, 62-71.5]; P = .004) than those without PA. In addition, patients with PA had significantly lower hemoglobin (8.3 g/dL [IQR, 7.5-8.95] vs 9.2 g/dL [IQR, 8.38-10.1]; P < .001) and fetal hemoglobin (6.4% [IQR, 3.6-12.4] vs 10.5% [IQR, 5.25-16.1]; P = .006) levels compared with those without PA. As expected, patients with PA had higher median urine ACR (158.8 mg/g [IQR, 101.6-466] vs 12.3 mg/g [IQR, 7.9-21.6]; P < .001). Greater proportions of patients with PA had eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 estimated using the cystatin C–derived CKD-EPI 2012 equation (7 [12%] vs 2 [2%]; P = .011) or the creatinine-derived CKD-EPI 2021 equation (5 [8%] vs 1 [1%]; P = .027). Baseline values of other laboratory and clinical variables in patients who had follow-up data are found in Table 1.

Development of new-onset PA

Among patients with follow-up data, 119 (66.9%) did not have PA at baseline, of whom 66 were female (55.5%). The median follow-up duration for patients with follow-up data was 937.5 days (IQR, 722-1130). New-onset PA was observed in 20 patients (16.8%) after a median of 770 days (IQR, 734-1156) of follow-up, whereas 99 patients (83.2%) did not develop PA after a median of 922 days (IQR, 705- 1114) of follow-up. The baseline characteristics of patients with and without new-onset PA were generally similar, although patients who developed new-onset PA had significantly higher baseline urine ACR values (36.2 mg/g [15.1-64.5] vs 11 mg/g [6.5-17.95]; P < .001) (supplemental Table 1). Patients with new-onset PA had significantly higher white blood cell (WBC) counts (10.1 × 109/L [8.4-11.6] vs 8.4 × 109/L [5.9-10.8]; P = .023) and SBP (122.5 mm Hg [114-128.8] vs 116 mm Hg [107.5-121.8]; P = .022) at the time of diagnosis than those without new-onset PA (Table 2). As expected, the urine ACR values were significantly higher in patients with new-onset PA at diagnosis (174.4 mg/g [65.4-231] vs 11.4 mg/g [6.6-20.1]; P < .0001) than patients without new-onset PA at last follow-up. Fewer patients with new-onset PA were receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) compared with patients without PA (3 [15%] vs 48 [48%]; P = .012).

Modeling new-onset PA using logistic regression as a function of each characteristic at baseline and baseline urine ACR, none of the baseline variables were significantly associated with PA (data not shown).

Progression of CKD

Using the cystatin C–derived CKD-EPI 2012 equation, the number of patients with CKD, defined as eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at the baseline, were 9 (5%) and 31 (17%), respectively. Using the creatinine-derived CKD-EPI 2021 equation, the number of patients with CKD, defined as eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at the baseline, were 6 (3%) and 19 (11%), respectively. In patients without CKD at baseline, CKD progression, defined as a decline in eGFR to <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with ≥25% decrease from baseline, was observed in 23 patients (13%) and 50 patients (29%), respectively, using the cystatin C–derived CKD-EPI 2012 equation. In patients without CKD at baseline, using the creatinine-derived CKD-EPI 2021 equation, CKD progression (decline in eGFR to <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with ≥25% decrease from baseline) was observed in 11 patients (6%) and 19 patients (11%), respectively.

Estimating GFR with the cystatin C–based CKD-EPI 2012 equation, we evaluated the variables, at baseline, that were associated with CKD progression. Patients with CKD progression (eGFR threshold of <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) were significantly older (39 years [IQR, 30.5-46] vs 28 years [IQR, 23-37]; P = .002), had higher SBP (122 mm Hg [IQR, 114-134.5] vs 113 mm Hg [IQR, 106.8-122]; P = .001), and had higher urine ACR (116.8 mg/g [IQR, 21.8-297.9] vs 17.95 mg/g [IQR, 9.1-76.8]; P = .006) but had lower hemoglobin (7.5 g/dL [6.5- 8.8] vs 9 g/dL [8.2-10]; P < .0001), absolute reticulocyte counts (150.1 × 109 [106.5-193.7] vs 212 × 109 [133.4-299.3]; P = .012), and eGFR (79.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [66.5-107.2] vs 125.7 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [109.1-136]; P < .0001) at baseline than those without CKD progression (Table 3). Patients with CKD progression were also more likely to have a history of leg ulcers (5 [22%] vs 7 [5%]; P = .01) and be on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (10 [43%] vs 23 [15%]; P = .003) at baseline than those without CKD progression. Using a threshold of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2, patients with CKD progression also had significantly higher SBP (118.5 mm Hg [110-129.3] vs 113 mm Hg [107-122]; P = .04), lower hemoglobin (8.6 g/dL [7.5-9.3] vs 9.1 g/dL [8.2-10.1]; P < .0001), and lower eGFR (114.4 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [84.3-127.1] vs 126.6 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [106.8-137.7]; P = .003) at baseline than those without CKD progression (Table 4).

Using the creatinine-derived CKD-EPI 2021 equation, patients who had CKD progression (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2) were significantly older (43 years [IQR, 32-54.5] vs 29 years [IQR, 23-38]; P = .014) and had higher urine ACR (158.8 mg/g [IQR, 48.4-1209.1] vs 19 mg/g [IQR, 9.1-85.3]; P < .0001) but had lower hemoglobin (7.4 g/dL [IQR, 6.35-7.55] vs 9 g/dL [IQR, 8.2-9.9]; P < .0001) and eGFR (69.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [IQR, 58.7-86.7] vs 126.6 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [IQR, 114.1-133.9]; P < .0001) at baseline than patients without CKD progression (Table 3). Patients with CKD progression were more likely to have a history of leg ulcers (3 [27%] vs 10 [6%]; P = .042) and to be on ACE inhibitors/ARBs (6 [55%] vs 28 [17%]; P = .007) at baseline than patients without CKD progression. Using a threshold of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2, patients with CKD progression were significantly older (38 years [IQR, 27.5-47] vs 28 years [IQR, 23-38]; P = .02), had lower hemoglobin (7.6 g/dL [IQR, 7.3-8.95] vs 9 g/dL [IQR, 8.2-9.9]; P = .007), had lower absolute reticulocyte counts (126 × 109 [IQR, 100.9-187.9] vs 211.7 × 109 [IQR, 132.4-294.6]; P = .01), and had lower eGFR (100.0 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [IQR, 66.2-120.9] vs 126.7 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [IQR, 114.4-133.9]; P < .0001) (Table 4).

Association of research biomarkers with new-onset PA

At the baseline visit, urinary AGT (8.82 ng/mg [IQR, 6.08-28.3] vs 5.1 ng/mg [IQR, 3.46-7.85]; P < .0001), KIM-1 (0.85 ng/mg [IQR, 0.56-1.21] vs 0.50 ng/mg [IQR, 0.36-0.77]; P < .0001), and soluble VCAM-1 (1196.1 ng/mL [IQR, 961.3-1565.8] vs 978.9 ng/mL [IQR, 807.7-1261.4]; P = .001) were significantly higher in patients with PA compared with those without PA (Table 5). Urinary nephrin was higher in patients with PA than in those without PA (32.4 ng/mg [24.7-40.4] vs 27.7 ng/mg [21.1-35.5]; P = .06), but the difference was not statistically significant.

In patients without PA at the baseline visit who had follow-up data, urinary AGT, KIM-1, urinary nephrin, and soluble VCAM-1 were not significantly different at baseline between those who subsequently developed PA and those who did not (supplemental Table 2). However, patients with new-onset PA had significantly higher urinary AGT at the time of diagnosis compared with those who did not develop PA at their last follow-up visit (17.6 ng/mg [IQR, 13.5-32.1] vs 8.99 ng/mg [IQR, 6.7-16.1]; P = .02). No significant differences were observed in urinary nephrin, KIM-1, or the level of soluble VCAM-1 when both patient groups were compared (supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, the change in urinary AGT from baseline to diagnosis of PA or last available follow-up was significantly higher in patients with new-onset PA compared with those without PA (21.2 ng/mg [IQR, 12.6-26.5] vs 3.8 ng/mg [IQR, 0.97-11.7]; P = .006). No significant differences were observed in the change from baseline in KIM-1 (0.31 ng/mg [0.18-0.44] vs 0.21 ng/mg [−0.01 to 0.6]; P = .48), urinary nephrin (11.7 ng/mg [6.8-20.5] vs 11.8 ng/mg [2.6-19.4]; P = .56), and soluble VCAM-1 (158.1 ng/mL [44.3-380.5] vs 36 ng/mL [−134.6 to 240.4]). Using a linear mixed effects model, we did not observe a statistically significant association of urine ACR as a function of change in urinary AGT (data not shown). The time and AGT interaction term was not significant, and after removal of the interaction term, urinary AGT was not significant.

In sensitivity analyses, with exclusion of patients with baseline urine ACR ≥30 mg/g, no significant differences were observed in baseline research biomarkers in patients who developed new-onset PA vs those who did not (data not shown). However, in patients with new-onset PA, urinary AGT remained significantly higher at the time of diagnosis compared with those who did not develop PA at their last follow-up visit (16.4 ng/mg [IQR, 13.9-28.5] vs 8.6 ng/mg [IQR, 6.4-16.2]; P = .02). No significant differences were observed with other biomarkers.

Association of research biomarkers with progression of CKD

At the baseline visit, urinary AGT (8.03 ng/mg [IQR, 6.04-14.5] vs 5.5 ng/mg [IQR, 3.5-9.99]; P = .015) and soluble VCAM-1 (1434.5 ng/mL [IQR, 1160.5-1861.6] vs 1011.2 ng/mL [IQR, 833.5-1271.5]; P < .0001) were significantly higher in patients with CKD progression (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 using the cystatin C–based CKD-EPI 2012 equation) compared with those who did not (Table 6). No significant differences were found in urinary KIM-1 or nephrin at the baseline visit. Using a cutoff value of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 to define CKD progression, the plasma level of soluble VCAM-1 (1217.3 ng/mL [IQR, 948.4-1525.3] vs 993.1 ng/mL [IQR, 809.5-1269.1]; P = .003) was significantly higher at the baseline visit in patients with CKD progression, but no significant differences were observed in urinary AGT, KIM-1, and urinary nephrin (supplemental Table 4).

Urinary AGT (18.6 ng/mg [IQR, 9.60-26.2] vs 5.9 ng/mg [IQR, 3.6-9.95]; P = .018) and soluble VCAM-1 (1792.1 ng/mL [IQR, 1317.0- 2173.4] vs 1039.8 ng/mL [IQR, 843.4-1320.3]; P = .007) at the baseline visit were significantly higher in patients with CKD progression (eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with the creatinine-based CKD-EPI 2021 equation) compared with those without CKD progression (Table 6). No significant differences in KIM-1 (1.21 ng/mg [IQR, 0.7-1.63] vs 0.63 ng/mg [IQR, 0.39-0.94]; P = .08) and urinary nephrin (33.8 pg/mL [IQR, 26.3-38.7] vs 28.3 pg/mL [IQR, 21.3-37.2]; P = .64) at the baseline visit were found in patients with and without CKD progression. Using a threshold of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 to define CKD progression, no significant differences were observed in urinary AGT, KIM-1, nephrin, and soluble VCAM-1 at the baseline visit when patients with and without CKD progression were compared (supplemental Table 4).

Following adjustments for baseline urine ACR and eGFR, only soluble VCAM-1 was significantly associated with CKD progression defined using a cutoff eGFR of <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with the cystatin C–based CKD-EPI 2012 equation (1101 ng/mL [standard error, 36.1] vs 1263 ng/mL [standard error, 52.5]; P = .05) (supplemental Table 5).

We further applied generalized estimating equations to model CKD as a function of time-dependent soluble VCAM-1, time-dependent eGFR, and time. We observed a significant association with soluble VCAM-1 only when CKD progression was defined based on eGFR <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 using the cystatin C–based CKD-EPI 2012 equation (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 1.0-1.02; P = .002) (supplemental Table 6). However, with the small number of patients with CKD progression, these results may be unreliable.

Discussion

The ability to predict the development of PA and progressive kidney disease could facilitate the development of early interventional therapies to prevent CKD and potentially decrease mortality in SCD. Although the natural history of CKD in sickle cell anemia remains incompletely defined, increasing evidence suggests that the nephropathy of SCD is progressive.3,4,19,20 Our current study provides prospective data on the development of PA, CKD progression, and the factors associated with these complications.

We observed that 16.8% of patients developed new-onset PA, whereas CKD progression was observed in up to 29% of patients. The significantly higher WBC counts in patients with new-onset PA may reflect a higher proinflammatory state with PA in SCD. SCD is described as a chronic inflammatory disease,21 although the contribution of inflammation to end-organ injury is not well characterized. Several inflammatory mediators have been reported to be associated with kidney disease in patients with SCD. Multiple studies reveal that endothelin-1, an inflammatory mediator, plays an important role in the pathogenesis of albuminuria in SCD.22,23 Children with sickle cell anemia and albuminuria had significantly higher urinary levels of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines than those with normal albuminuria.24 Consistent with previous studies revealing higher SBP in patients with SCD with albuminuria,10,11,25 patients with new-onset PA also had higher SBP at the time of diagnosis than those without new PA. Although it is uncertain whether elevated SBP is a cause or consequence of kidney disease in SCD, adequate control of SBP is necessary to prevent the worsening of kidney function. The finding that fewer patients with new-onset PA were on treatment with NSAIDs compared with patients without PA is likely a result of avoidance of NSAIDs in these patients in a bid to decrease worsening kidney injury and function.26

The factors associated with CKD progression (<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with ≥25% decrease from baseline) at baseline were similar when eGFR was estimated using the cystatin C–based and creatinine-based equations. Similar to the finding with PA and as observed in other studies,4,20 higher SBP level was associated with CKD progression. In addition, similar to the findings from a single-center, retrospective, cohort study,27 we observed that patients with CKD progression had lower baseline hemoglobin levels than those without CKD progression. As the patients with CKD progression had lower baseline eGFR values, the lower hemoglobin levels may be a result of reduced erythropoietin production or may reflect more severe disease in these patients. The presence of increased baseline urine ACR in patients with CKD progression confirms the previous reports that albuminuria is a risk factor for progressive decline in kidney function.3,4,27,28 Several small studies have reported on the short-term efficacy of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in decreasing albuminuria in SCD.29-31 The observation that patients on treatment with ACE inhibitors/ARBs were significantly more likely to have CKD progression is likely because these renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blocking agents are largely administered to those with albuminuria who are at high risk for progressive kidney disease. Indeed, in a retrospective study, patients with SCD receiving ACE inhibitors/ARBs were found to have a slower eGFR decline than those not receiving such therapy.8

Similar to that in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and other kidney diseases,32-38 urinary AGT is significantly higher in individuals with sickle cell anemia with PA than in those without.9,10 Our current study confirms and extends our previous findings that urinary AGT is higher in patients with PA than in those without PA. We observed significantly higher urinary AGT after the development of new-onset PA compared with patients who did not develop PA. Similarly, we observed a statistically significant association of the change in urinary AGT (from baseline to diagnosis) with PA. Although a significant association of urine ACR as a function of change in urinary AGT was not observed, this may be related to inconsistent measurements of these variables and the small number of patients with follow-up data. Urinary AGT at baseline was significantly higher in patients who developed CKD progression compared with those who did not, although it was not significantly associated with CKD progression after adjustment for baseline urine ACR and eGFR. Longitudinal studies of patients with type 2 diabetes report a significant correlation of urinary AGT with urine ACR and inverse correlations of the change in urinary AGT with the change in eGFR.39,40 In a prospective study of patients followed for a median of 6.3 years, the risk of the composite renal event (decline in kidney function and onset of end-stage kidney disease during the follow-up) was significantly higher in the fifth quintile by urinary AGT/urine creatinine ratio compared with that in the first quintile.41 With the small number of patients with follow-up data and inconsistent evaluation of biomarkers, we are unable to ascertain whether increased urinary AGT is predictive or a consequence of kidney damage in SCD. However, based on the preponderance of data revealing associations of urinary AGT with albuminuria and CKD progression, more longitudinal studies with larger patient populations and with consistent evaluation of biomarkers are required to evaluate the predictive capacity of urinary AGT for development of PA and CKD progression.

We also confirm and extend our previous finding that the plasma level of soluble VCAM-1 is higher in patients with PA than in those without PA.10 Furthermore, the level of soluble VCAM-1 at baseline was significantly higher in patients who developed CKD progression compared with those who did not, and remained so after adjustment for baseline urine ACR and eGFR. Soluble VCAM-1 is a marker of endothelial activation which reflects increased systemic inflammatory stress.42 The association of soluble VCAM-1 with PA and CKD progression provides further evidence for the role of impaired endothelial function in the pathogenesis of SCD-related kidney disease.43-45 More studies are required to confirm the predictive capacity of soluble VCAM-1 for progressive kidney disease in SCD and to test the effect of therapies that improve endothelial function. Although we have previously evaluated the effect of atorvastatin on endothelial function and PA in SCD, the treatment duration was short, and the study was not adequately powered to reveal treatment effects.46

Despite its multiple strengths, this study was limited by the small number of patients with follow-up data and inconsistent follow-up and biomarker measurements. The study was substantially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which period research activities were paused or restricted, resulting in missed visits and withdrawals. We acknowledge the limitation of using a single urinary ACR ≥100 mg/g as a definition for PA due to the small number of patients with follow-up data. However, several studies in SCD reveal a high probability of this cutpoint for PA.3,9 The higher baseline urine ACR in patients who subsequently developed PA is a consequence of the definition we adopted. Although there is a small possibility that a few individuals with single baseline urine ACR values of between 30 and 100 mg/g may have PA, our sensitivity analysis revealed that soluble VCAM-1 remained significantly associated with CKD progression after adjustments for baseline urine ACR and eGFR. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses confirmed that urinary AGT was higher in patients with new-onset PA after excluding those with baseline urine ACR ≥30 mg/g. We did not evaluate genetic risk factors associated with albuminuria.

In this prospective cohort study, we confirm that increased urine ACR is a risk factor for CKD progression. The associations with comorbid conditions (increased SBP) and measures of disease severity (increased WBC count) suggest contributions of these factors to the development of PA and CKD progression. Finally, the association of baseline levels of soluble VCAM-1 with CKD progression suggests that this biomarker may predict progressive decline of kidney function in SCD. More studies with consistent evaluation of biomarkers are required to further evaluate the predictive capacity of urinary AGT and soluble VCAM-1 for PA development and CKD progression in SCD.

Acknowledgment

Funding for this study was provided by US Food and Drug Administration grant R01FD006030 (K.I.A., principal investigator).

Authorship

Contribution: K.I.A. designed and directed the study, and wrote the manuscript; U.O.O. and M.N. assisted in participant identification and manuscript preparation; L.E. processed the samples, analyzed the biomarkers, and assisted with manuscript preparation; K.L.P., D.W., and P.M. recruited study participants and assisted in sample collection; L.C.S., W.G., and W.H.W. assisted with analysis of the biomarkers; M.R. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; and P.C.D. and V.K.D. directed the study and assisted with manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.I.A. is a member of the board of trustees of Vitalant; has received research funding from Novartis and Novo Nordisk; has served on advisory boards for Agios Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi; is a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline; and is a member of the data monitoring committee for Vertex Pharmaceuticals. U.O.O. serves as a consultant for Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Novo Nordisk; and has served on advisory board for Bluebird Bio and Fulcrum Therapeutics. V.K.D. is a board member of the Vasculitis Foundation (unpaid); has served as a consultant for Novartis, Travere Therapeutics, Bayer, Forma Therapeutics, Merck, Amgen, iCell Gene Therapeutics, and Vera Therapeutics; and has received royalties from UpToDate. P.C.D. has received honoraria from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Bluebird Bio, and Chiesi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Kenneth I. Ataga, Division of Hematology, Center for Sickle Cell Disease, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center at Memphis, 956 Court Ave, Suite D324, Memphis, TN 38163; email: kataga@uthsc.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available from the corresponding author, Kenneth I. Ataga (kataga@uthsc.edu), on reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.