Key Points

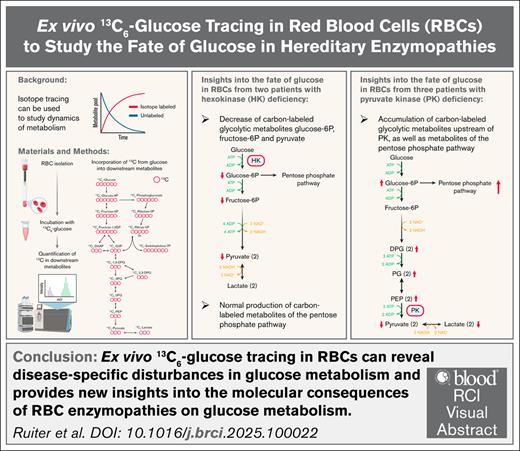

Ex vivo 13C6-glucose tracing in RBCs can reveal disease-specific disturbances in glucose metabolism.

Ex vivo 13C6-glucose tracing provides new insights into the molecular consequences of RBC enzymopathies on glucose metabolism.

Visual Abstract

As the maturing red blood cell (RBC) loses its nucleus and organelles including mitochondria to maximize capacity for oxygen transportation, it becomes dependent on glycolysis for the generation of adenosine triphosphate. RBC enzymopathies are a group of hereditary nonspherocytic hemolytic anemias in which impaired cellular energy balance decreases RBC integrity and life span. In this study, we monitored the fate of glucose through glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) over time in purified RBCs from controls and patients with hexokinase (HK) or pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency. We combined 13C6-glucose tracing and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to quantify incorporation of the 13-labeled carbon atoms from glucose into downstream metabolites. We observed reduced carbon labeling of glycolytic metabolites downstream of HK in RBCs from HK-deficient patients compared to controls, whereas carbon labeling of metabolites of the PPP was similar to controls. In RBCs from PK-deficient patients, we quantified accumulation of carbon-labeled glycolytic metabolites directly upstream of PK compared to controls, but noted decreased carbon labeling of metabolites more upstream in the glycolytic pathway. This result was accompanied by increased carbon labeling of metabolites of the PPP compared to controls. Our findings provide new insights into the consequences of the respective enzyme deficiencies and demonstrate the suitability of ex vivo 13C6-glucose tracing in RBCs to study disease-specific disturbances in glycolysis. This technique can be applied to RBCs from patients with various RBC disorders to generate a better understanding of metabolic disturbances in hereditary anemias.

Introduction

The main role of the red blood cell (RBC) is transportation and exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the lungs and body tissues. During the maturation of erythroid precursors to reticulocytes and, ultimately, mature RBCs, the nucleus and organelles are lost to maximize capacity for oxygen transportation.1 Because mature RBCs have no mitochondria, they rely solely on glycolysis for the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy source needed to fuel key cellular processes. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) branches from glycolysis and produces reduced NAD phosphate (NADPH). NADPH is required to provide the RBC with sufficient amounts of reduced glutathione, the main defense mechanism of RBCs against oxidative stress.2 Another important pathway that branches from glycolysis is the Rapoport-Luebering shunt, which produces the metabolite 2,3-diphosphoglycerate. This metabolite binds to hemoglobin, thereby regulating its oxygen affinity and, hence, the release of oxygen in tissues.3

Hereditary RBC enzymopathies are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders in which metabolic enzymes are affected. Clinical symptoms of RBC enzymopathies include anemia, fatigue, (neonatal) jaundice, splenomegaly, and signs of hemolysis, such as decreased hemoglobin, reticulocytosis, and hyperbilirubinemia.4 Some RBC enzymopathies manifest clinically in other tissues as well, such as muscle and the central nervous system.5 The severity of symptoms differs greatly between affected individuals, and these symptoms are also observed in other forms of hemolytic anemia, causing RBC enzymopathies to be often misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed.6

The most common RBC enzymopathy (estimated to affect >500 million individuals) is glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.7 G6PD is the first enzyme of the PPP that catalyzes the oxidation of glucose-6-phosphate to 6-phosphogluconolactone, during which NADPH is produced. G6PD deficiency makes RBCs vulnerable to oxidative damage, and therefore susceptible to hemolysis. Other RBC enzymopathies are extremely rare. The most frequently occurring glycolytic enzyme deficiency in RBCs is pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency. PK catalyzes the transfer of the phosphoryl group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to adenosine diphosphate in the penultimate step of glycolysis, thereby generating pyruvate and ATP. The prevalence of PK deficiency is estimated to be 51 cases per million in the Western population, of which only ∼5 per million are diagnosed.8 Even rarer is the deficiency of hexokinase (HK),9 which catalyzes the phosphorylation of glucose using ATP as phosphoryl donor in the first step of glycolysis. To date, ∼30 cases of HK deficiency have been described.9,10 Glycolytic enzymopathies cause a continuous lack of energy, ultimately decreasing RBC life span and manifesting clinically as nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia.11 Deficiencies in other glycolytic enzymes, such as glucose phosphate isomerase, phosphofructokinase, aldolase, triosephosphate isomerase, and phosphoglycerate kinase, are also known to cause hemolytic anemia.11

Several studies have focused on the effects of glycolytic enzymopathies on RBC metabolism.12-17 In these studies, metabolite levels are often measured at a static time point. Given that metabolism is a dynamic process and metabolite levels are regulated both by production and consumption rates, measuring at a static time point limits the interpretation of the results. For example, PK deficiency is characterized by decreased adenine nucleotide pools,18 and it was long unclear whether this resulted from decreased production or increased consumption of adenine nucleotides. Zerez et al19,20 showed that the rate of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate formation, the precursor of adenine nucleotides, was decreased in PK-deficient RBCs. These results suggest a decreased production of adenine nucleotides in PK deficiency and highlight the relevance of studying the dynamics of metabolism.

Isotope tracing is a suitable approach to study the dynamics of metabolism.21 In this study, we performed glucose tracing in purified RBCs to monitor the fate of glucose through glycolysis and the PPP over time. We used 13C6-glucose and quantified the incorporation of 13-labeled carbon atoms into downstream metabolites with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. We included RBCs from controls and patients with HK or PK deficiency to study the fate of glucose in the context of these glycolytic enzyme deficiencies, aiming to assess the suitability of this approach for studying glucose metabolism in RBCs under normal and pathophysiological conditions.

Methods

Sample collection

Whole blood from 10 controls (5/5: female/male, age range, 23-49 years, median age: 36 years), 2 patients with HK deficiency, and 3 patients with PK deficiency was collected into heparin tubes for glucose tracing and into tubes with EDTA for enzyme activity measurements. Whole blood from controls was collected by the ethically approved blood donor service of our institution (NedMec, protocol number: 18/774).

RBC characteristics

Routine hematological variables, including reticulocyte count, were measured using a Cell-Dyn Sapphire (Abbott Diagnostics). RBCs were purified using columns with cellulose (1:1 weight-to-weight ratio of α-cellulose and cellulose type 50 [Sigma-Aldrich] in 0.9% NaCl) to deplete leukocytes and platelets.22 PK and HK activity measurements were performed on the lysates of RBCs from all the patients as described previously.6,22,23 Considering that both PK and HK activity are strongly influenced by RBC age,24 the PK/HK ratio was used to evaluate enzymatic activity in light of reticulocytosis that is often present.

Glucose tracing

Purified RBCs were incubated in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium (Cell Culture Technologies) containing 11 mM glucose for 30 minutes at 37°C in a tube rotator to obtain a steady state (final concentration of 1 × 109 cells per mL, final glucose concentration of ∼9 mM). The cells were washed with a 0.9% NaCl solution, and for each time point, they were resuspended in glucose-free RPMI (Cell Culture Technologies) supplemented with 11 mM 13C6-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) or resuspended in RPMI containing 11 mM of glucose as a blank. The cells were incubated with 13C6-glucose at 37°C in a tube rotator for 0 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, and 6 hours. After incubation, the cells were centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the medium was collected. The cells were washed twice in an ice-cold 0.9% NaCl solution. The cells were then lysed in ice-cold ultrapure H2O, followed by the addition of 100% methanol to the lysed cells to a final ratio of 20:80 (H2O/methanol). Samples were thoroughly vortexed and centrifuged at 17 000g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The cell extracts in methanol and collected medium were stored at –80°C until measurement with liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS).

LC-HRMS for the measurement of glycolytic and PPP metabolites

The quantitative analysis of glycolytic and PPP metabolites was performed as previously described.25 Metabolites were measured in cell extracts (1 × 108 cells) and collected medium before and after glucose tracing. 2H5-lactate (100 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) and 2H7-glucose (133 μM, Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each sample as internal standard. Before analysis, the samples were evaporated under a flow of nitrogen at 40°C and reconstituted in ultrapure H2O/acetonitrile (50:50). The samples were analyzed using an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The injection volume was 6 μL, and the autosampler was set to 15°C. Chromatic separation was performed using an Atlantis Premier BEH Z-HILIC Column (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters). Solvent A was 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 9.0) in ultrapure H2O, and solvent B was 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 9.0) in acetonitrile. The column temperature was 40°C with the following flow rates and gradients: linear from 90% to 65% B from 0 to 5 minutes (flow rate: 0.5 mL/min), isocratic 65% B from 5 to 6 minutes (flow rate: 0.5 mL/min), linear from 65% to 90% B from 6 to 6.5 minutes (flow rate: 0.65 mL/min), isocratic 90% B from 6.5 to 12 minutes (flow rate 0.65 mL/min), and isocratic 90% B from 12 to 12.5 minutes (flow rate: 0.5 mL/min) to reach starting conditions. Analytes were recorded via a full scan with a mass resolving power of 120 000 over a mass range from 70-900 mass-to-charge ratio (automated gain control target value: 106, radio frequency lens: 75, maximum injection time: 200 millisecond). The heated electrospray ionization source parameters were set to the following values: spray voltage of 4.0 kV (positive mode) and 3.5 kV (negative mode), sheath gas of 345 kPa, auxiliary gas of 103 kPa, sweep gas of 0 Pa, ion transfer temperature of 350°C, and auxiliary gas heater temperature of 400°C. Data were acquired using Xcalibur software (version 3.0; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

LC-HRMS for the measurement of ATP

The quantitative analysis of ATP was performed as previously described.26 ATP was extracted from purified RBCs using ultrapure H2O and methanol (20:80), and was then diluted 5× in acetonitrile. In addition, 13C1015N5-ATP (200 μM, MedChemExpress) was added to each sample as internal standard. Chromatic separation was performed using a BioBasic AX column (2.1 × 50 mm, 5 μm, Thermo Scientific). The injection volume was 5 μL. Solvent A was 5 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile/ultrapure H2O (20/80) containing 0.1% acetic acid, and solvent B was 10 mM ammonium acetate in acetonitrile/ultrapure H2O (20/80) containing 0.5% ammonium hydroxide. The column temperature was 40°C, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and the following gradient: linear from 30% to 50% B from 0 to 1.5 minute, linear from 50% to 100% B from 1.5 to 2.0 minutes, isocratic 100% B from 2.0 to 3.5 minutes, linear from 100% to 30% B from 3.5 to 3.6 minutes, isocratic 30% B (initial solvent conditions) from 3.6 to 5.5 minutes to equilibrate the column. Metabolites were detected using an electrospray ionization source operating in negative ion mode over a scan range of 200-600 mass-to-charge ratio. Data were acquired using Xcalibur software (version 3.0; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Data analysis

For the integration of the raw data peaks, TraceFinder 5.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. Glycolytic and PPP metabolite concentrations were calculated based on a calibration curve of the corresponding metabolite ranging from 0.2 to 100 μM. The concentration of ATP was calculated based on a calibration curve ranging from 0.004 to 2.0 mg/mL. Nonlinear regression one-phase association analysis was used in GraphPad Prism (Version 10.1.2) for curve fitting.

All patients provided verbal and written informed consent before enrollment in this study (approved by the ethical committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht, NedMec, protocol number: 21/793), and all procedures were conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

Two HK-deficient patients (HKD1-2), including 1 who was transfusion-dependent (HKD1), and 3 PK-deficient patients (PKD1-3), including 1 who was transfusion-dependent (PKD1), were included. The transfusion of 2 units is scheduled every 3 to 4 weeks for HKD1 and every 4 to 5 weeks for PKD1. Blood was drawn from the patients that were transfusion-dependent just before the upcoming transfusion. PKD3 receives irregular transfusions and did not receive any transfusions in the 3 months before this study. In addition, HKD1, PKD1, and PKD3 receive deferasirox to reduce iron overload and have had a splenectomy. Clinical characteristics, hematological variables, and enzyme activities of all patients are summarized in Table 1. The diagnosis of the patients was previously confirmed based on molecular characterization of the HK1 or PKLR gene. Variants are described in supplemental Table 1.27-29

13C6-glucose tracing

We measured the levels of unlabeled glucose and 13C6-glucose before and during the tracing experiment. No 13C6-glucose was detectable in the medium before the start of the tracing experiment, and negligible amounts of unlabeled glucose remained in the medium at the start of the tracing experiment (supplemental Figure 1A). Therefore, we conclude that only 13C6-glucose was consumed by the cells over a time course of 6 hours. We confirmed 13C6-glucose consumption by measuring the decrease in 13C6-glucose in each patient and control sample over time. Given that 13C6-glucose concentrations were similar to physiological blood glucose concentrations and RBCs account for only a trivial proportion of blood glucose consumption, we expected a minor decrease in glucose concentration after 6 hours. We observed a mean decrease of 12.8% ± 3.7% in glucose concentration in controls after 6 hours and no difference in glucose uptake from the medium among controls, HK-deficient patients, and PK-deficient patients (supplemental Figure 1B).

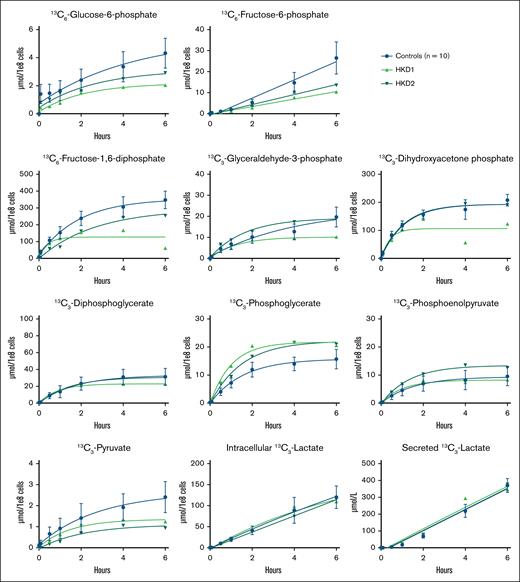

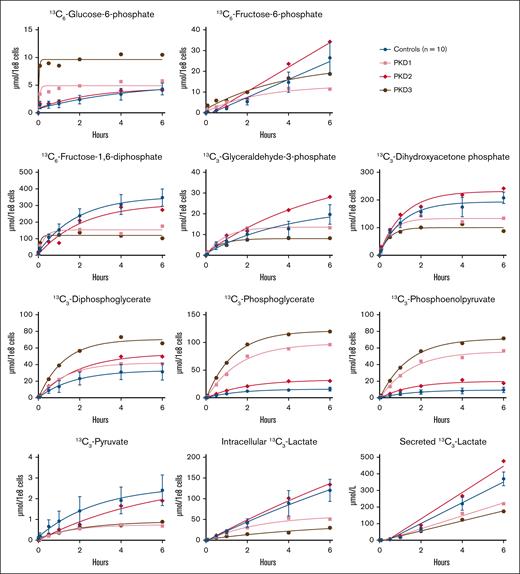

Effect of HK deficiency on glycolysis

Considering that HK catalyzes the first step of glycolysis, HK deficiency could lead to the reduced incorporation of labeled carbon atoms from glucose in all downstream glycolytic intermediates. The results of the glucose tracing in RBCs from HK-deficient patients are shown in Figure 1. We observed a decreased production of carbon-labeled glucose-6-phosphate in HKD1 over the complete time course of 6 hours, whereas this was only slightly lower in HKD2 compared to controls. Both patients showed a decrease in the production of carbon-labeled fructose-6-phosphate and fructose-1,6-diphosphate. The production of carbon-labeled glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate was also decreased in HKD1, but it was normal in HKD2 compared to controls. HKD1 reached a plateau for label incorporation in fructose-1,6-diphosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and dihydroxyacetone phosphate already after 1 to 2 hours, whereas controls and HKD2 reached a plateau after 4 to 6 hours. Interestingly, we observed a slight increase in the production of carbon-labeled phosphoglycerate in both patients compared to controls. Both patients had a decreased production of carbon-labeled pyruvate, whereas the production of carbon-labeled lactate (both intracellular and secreted) was comparable with that of controls. For a selection of metabolites, we also calculated the relative contribution of each carbon-labeled metabolite to the total pool of that metabolite. This result showed a relative decrease in glucose-6-phosphate and pyruvate (supplemental Figure 2A). Therefore, a higher percentage of the pool of these metabolites exists in the unlabeled form, indicating stalled production of these metabolites, whereas the total metabolite pool is not markedly affected. To correlate these metabolic changes to energy metabolism, we measured the levels of ATP. We observed slightly lower levels of ATP in HKD2, but no differences in the levels of ATP in HKD1 (supplemental Figure 3).

Carbon labeling of glycolytic metabolites in patients with HK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls and 2 patients (HKD1-2) with HK deficiency were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream glycolytic metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Lactate concentrations were measured both intracellularly and in the medium. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

Carbon labeling of glycolytic metabolites in patients with HK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls and 2 patients (HKD1-2) with HK deficiency were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream glycolytic metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Lactate concentrations were measured both intracellularly and in the medium. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

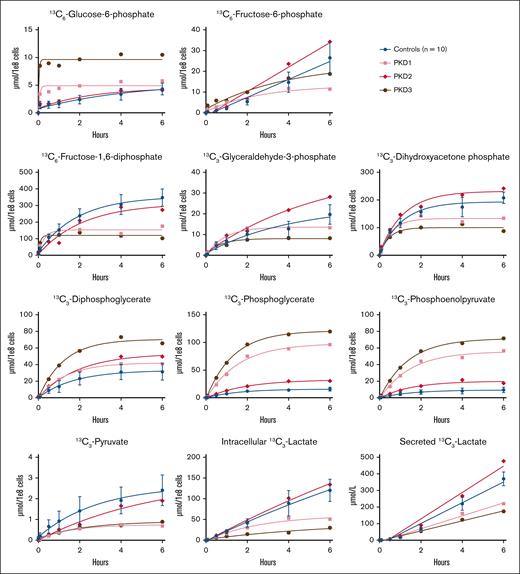

Effect of PK deficiency on glycolysis

A block at the PK step downstream in glycolysis could lead to the accumulation of labeled carbon atoms in metabolites upstream of PK in RBCs from PK-deficient patients, as well as a reduced incorporation of labeled carbon atoms in pyruvate and lactate, the metabolites downstream of PK. The results of the glucose tracing in RBCs from PK-deficient patients are shown in Figure 2. We observed an increased production of carbon-labeled glucose-6-phosphate, but a decreased production of carbon-labeled fructose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6-diphosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and dihydroxyacetone phosphate after 6 hours in PKD1 and PKD3 compared to controls. In PKD2, carbon-labeled glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate accumulated over time, whereas the production of carbon-labeled glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, fructose-1,6-diphosphate, and dihydroxyacetone phosphate was similar to that in controls. Although to different extents, all 3 PK-deficient patients showed increased production of carbon-labeled diphosphoglycerate, phosphoglycerate, and PEP, the metabolites upstream of PK. Interestingly, the production of carbon-labeled pyruvate and lactate (both intracellular and secreted) was markedly decreased in PKD1 and PKD3, but not in PKD2. Next, we calculated the relative contribution of each carbon-labeled metabolite to the total pool for a selection of metabolites. As opposed to the increased absolute levels of carbon-labeled PEP, we did not observe a relative increase in PEP (supplemental Figure 2B). This finding suggests that both unlabeled and newly produced carbon-labeled PEP accumulate and are not metabolized in patients with PK deficiency. Indeed, next to an absolute decrease in PKD1 and PKD3, we also noted a relative decrease in pyruvate in all 3 patients and in intracellular and secreted lactate in PKD1 and PKD3 (supplemental Figure 2B). We also measured the levels of ATP to correlate these metabolic changes to energy metabolism. However, we did not observe differences in the levels of ATP at baseline in all 3 patients with PK deficiency (supplemental Figure 3).

Carbon labeling of glycolytic metabolites in patients with PK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls and 3 patients (PKD1-3) with PK deficiency were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream glycolytic metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Lactate concentrations were measured both intracellularly and in the medium. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

Carbon labeling of glycolytic metabolites in patients with PK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls and 3 patients (PKD1-3) with PK deficiency were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream glycolytic metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Lactate concentrations were measured both intracellularly and in the medium. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

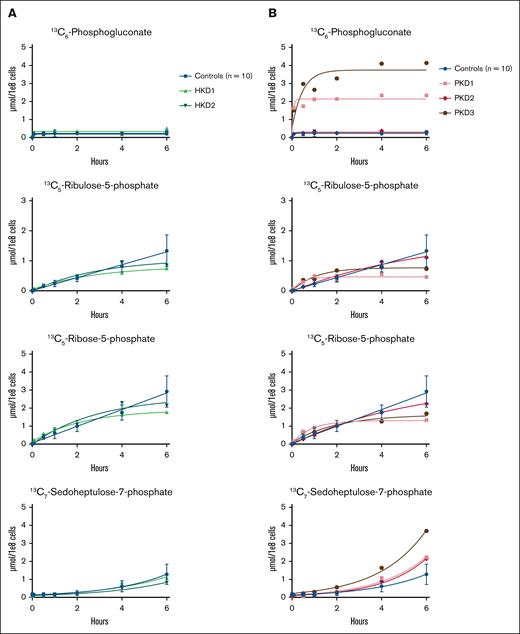

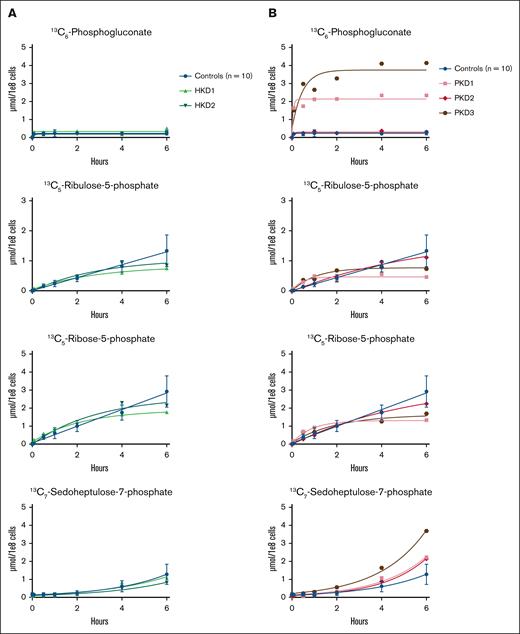

Effect of HK or PK deficiency on the PPP

The PPP branches off from glycolysis at the level of glucose-6-phosphate. Thus, we reasoned that there would be a reduced incorporation of labeled carbon atoms in PPP metabolites in patients with HK deficiency and an increased incorporation of labeled carbon atoms in PPP metabolites in patients with PK deficiency. The results of the glucose tracing toward the PPP in RBCs from HK-deficient patients are shown in Figure 3A. We showed that the production of carbon-labeled ribulose-5-phosphate and ribose-5-phosphate was slightly lower in both HK-deficient patients after 6 hours than in controls. However, the production of carbon-labeled 6-phosphogluconate and sedoheptulose-7-phosphate was comparable between controls and both HK-deficient patients. The results of the glucose tracing toward the PPP in RBCs from PK-deficient patients are shown in Figure 3B. We showed that carbon-labeled 6-phosphogluconate accumulated in PKD1 and PKD3, whereas the production of carbon-labeled ribulose-5-phosphate and ribose-5-phosphate was reduced after 6 hours compared to controls. Carbon-labeled sedoheptulose-7-phosphate accumulated in all 3 PK-deficient patients. The incorporation of labeled carbon atoms in the other metabolites of the PPP in PKD2 was comparable with that in controls.

Carbon labeling of the PPP metabolites in patients with HK or PK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls; 2 patients with HK deficiency (HKD1-2) (A) and 3 patients with PK deficiency (PKD1-3) (B) were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream PPP metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

Carbon labeling of the PPP metabolites in patients with HK or PK deficiency. Purified RBCs from 10 controls; 2 patients with HK deficiency (HKD1-2) (A) and 3 patients with PK deficiency (PKD1-3) (B) were incubated with 13C6-glucose. The incorporation of the labeled carbon atoms in downstream PPP metabolites was determined over time by quantifying the concentrations of carbon-labeled metabolites with LC-HRMS. Data points with error bars indicate mean and standard deviation.

Discussion

We combined 13C6-glucose tracing with mass spectrometry to quantify the incorporation of 13-labeled carbon atoms from glucose into downstream metabolites to study how RBCs metabolize glucose ex vivo. We included RBCs from 10 controls to establish methodological and biological variability. We then applied this method to HK- or PK-deficient RBCs to detect disease-specific disturbances in glucose metabolism using 13C6-glucose tracing. These disorders represent defects in the first and last part of glycolysis, respectively. Accordingly, we observed a reduction in the production of carbon-labeled metabolites directly downstream of HK in RBCs from HK-deficient patients, and accumulation of carbon-labeled metabolites directly upstream of PK in RBCs from PK-deficient patients. Therefore, we conclude that 13C6-glucose tracing is suitable to study glucose metabolism ex vivo in RBCs, both in healthy and pathophysiological conditions.

Glucose tracing studies have been performed previously in RBCs stored for transfusion by supplementing 13C-glucose to the storage medium.30-34 Furthermore, 13C-glucose tracing has been performed in RBCs ex vivo, where nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has been used to calculate the absolute flux through glycolysis or the PPP based on glucose and lactate measurements.35-38 Our method is unique in that we quantify the incorporation of labeled carbon atoms in individual intermediates of glycolysis and the PPP in RBCs over time, thereby generating a detailed and dynamic mechanistic insight in the fate of glucose.

We observed a reduction in the production of carbon-labeled metabolites downstream of HK in HK-deficient patients, which was more obvious in HKD1 compared to HKD2 despite similar HK activity and chronic transfusion therapy in HKD1. This more pronounced reduction in HKD1 is in line with the more severe hemolytic anemia in this patient, characterized by lower hemoglobin levels and a more pronounced reticulocytosis. Unexpectedly, the production of several carbon-labeled metabolites, such as diphosphoglycerate, PEP, and lactate, was comparable between controls and both HK-deficient patients. This finding has been previously reported in 1978 by Beutler et al,39 who observed a decrease in the levels of glucose-6-phosphate, but not in other glycolytic metabolites in a patient with HK deficiency. They also noted ATP levels to be somewhat lower than normal, which we also observed in HKD2. However, ATP levels were comparable between controls and HKD1, which could be a result of the higher number of reticulocytes that can produce ATP in residual mitochondria. Interestingly, our results also showed that the production of carbon-labeled metabolites of the PPP was comparable between controls and both patients despite the HK deficiency. This indicates that glucose-6-phosphate is preferentially directed toward the PPP, which confirms the findings from 1986 by Magnani et al40 in HK-deficient patient fibroblasts.

Among patients with PK deficiency, we observed clear accumulation of labeled carbon atoms in intermediates upstream of PK, which was accompanied by reduced carbon labeling of pyruvate and lactate in PKD1 and PKD3, 2 metabolites downstream of PK. PKD2 had normal pyruvate and lactate production, suggesting RBC metabolism is not markedly affected by the low RBC PK activity. This result is in line with the milder phenotype in this patient, characterized by a milder decrease in hemoglobin levels and lower reticulocytosis than in PKD1 and PKD3. Notably, not all metabolites upstream of PK accumulated in the PK-deficient patients. We observed a decreased production of carbon-labeled metabolites downstream of phosphofructokinase and upstream of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in PKD1 and PKD3. GAPDH uses NAD+ as a cofactor, which is normally recycled back during the conversion of pyruvate into lactate. As a consequence of impaired pyruvate to lactate conversion, the levels of reduced NAD+ (NADH) will accumulate. Increased NADH levels inhibit GAPDH activity, which can redirect glucose metabolism to alternative pathways such as the PPP. In line with this finding, we observed the accumulation of carbon-labeled metabolites of the PPP in PKD1 and PKD3.

RBC enzyme deficiencies are associated with an extremely heterogeneous phenotype, which is also represented in our patient cohort. PKD1 and PKD2 are compound heterozygous for 2 different PKLR variants. They share the c.507+1G>A p.(?) variant, but show highly distinct clinical characteristics. This clearly indicates that the phenotype is not solely determined by molecular properties of mutant proteins but rather reflects a complex interplay of physiological, environmental, and other (genetic) factors. PKD1 and PKD3 showed more pronounced metabolic changes, whereas their ATP levels were comparable with that of controls. This result appears paradoxical because PK is an ATP-producing enzyme in glycolysis, but it has been previously reported by others.41,42 Specific clinical features shared by PKD1 and PKD3 include increased reticulocyte count and prior splenectomy. Given that the spleen removes defective RBCs from the circulation, it is not surprising that the metabolic differences are more pronounced in splenectomized patients. In PK deficiency, splenectomy is known to increase the number of reticulocytes, suggesting PK-deficient reticulocytes are preferentially cleared from the circulation43,44 and indicating that reticulocytes are more affected by the enzyme deficiency. The enzymatic activity of HK and PK is known to decrease in the RBC with increasing RBC age; thus, HK and PK activity are higher in reticulocytes.45 Considering that these reticulocytes can produce ATP in residual mitochondria, it is hypothesized that reticulocytes have higher ATP levels, and therefore normal ATP levels could be indicative of a relative ATP deficiency when reticulocyte count is increased.15

The broad-scale metabolic disturbances have been studied previously in PK deficiency,14,15 showing increased levels of polyamines such as spermidine and spermine that play a role in protecting the membrane from oxidative stress,46 as well as increased levels of free (polyunsaturated/highly unsaturated) fatty acids and acyl-carnitines that play a role in membrane remodeling upon oxidative stress.47 These metabolic disturbances, along with relative PK deficiency, are also observed in other hereditary anemias such as sickle cell disease.48,49 Therefore, it would be interesting to trace other pathways with other isotopic-labeled metabolites to study, for example, polyamine metabolism and lipid/carnitine metabolism,50-52 and to apply tracing experiments to RBCs from patients with various RBC disorders. This will improve our understanding of metabolic disturbances in hereditary anemia. In light of the relative PK deficiency observed in various RBC disorders, activators of PK are currently being tested as a potential treatment option for these disorders.53-55 In addition, the method described here could be a useful tool to study the effect of such metabolic therapies on glucose metabolism ex vivo and could even allow for the in vitro prediction of responsiveness of patients to such a form of therapy.

The diagnosis of RBC enzymopathies ultimately depends on the identification of causative genetic mutations and the demonstration of decreased enzyme activity.56 The latter can be especially complicated in the presence of high reticulocyte counts and in patients who are transfusion-dependent. Nevertheless, the results of this study showed clear differences between patient and control RBCs, even when patients were transfused regularly. Moreover, the HK- and PK-deficient patients could easily be distinguished from each other, suggesting this method could also be used to identify other glycolytic enzymopathies.

To summarize, we demonstrated that ex vivo 13C6-glucose tracing in RBCs is a suitable approach to determine disease-specific disturbances in glycolysis. Furthermore, our findings provide new insights into the molecular consequences of HK or PK deficiency. In future studies, this technique can be applied to RBCs from patients with various RBC disorders to generate a better understanding of metabolic disturbances in hereditary anemias. Ultimately, this technique could be a useful tool for diagnosing patients with glycolytic enzymopathies and for studying the effects of (new) metabolic treatments.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients for their participation.

Authorship

Contribution: R.v.W. and J.J.M.J. designed and supervised the study; T.J.J.R. and B.A.v.O. performed the laboratory procedures; T.J.J.R. and J.G. performed the mass spectrometry measurements; J.R.A.d.W. and E.J.v.B. recruited the participants and collected patient data; T.J.J.R., R.v.W., and J.J.M.J. analyzed the data and wrote the original draft; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Judith J. M. Jans, Section Metabolic Diagnostics, Department of Genetics, University Medical Center Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, 3584 CX Utrecht, The Netherlands; email: j.j.m.jans@umcutrecht.nl.

References

Author notes

R.v.W. and J.J.M.J. contributed equally to this work.

Original data and detailed protocols are available on request from the corresponding author, Judith J. M. Jans (j.j.m.jans@umcutrecht.nl). Data will be shared in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation and European Union privacy laws.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.