Key Points

An in vitro model induces Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell exhaustion, allowing detailed phenotypic, metabolic, and transcriptomic analysis.

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells retain partial function and can be reactivated with anti-CD3 antibodies or TCEs.

Visual Abstract

Recent advancements in cancer immunotherapies have highlighted the potential of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells as key players in the immune response against cancer. Initially recognized for their broad activity in combating infections and tumors, these cells are now emerging as promising candidates for targeted immunotherapeutic strategies, such as T-cell engagers (TCEs). However, like other immune cells, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells can enter a state of dysfunction and exhaustion within the tumor microenvironment, driven by factors such as T-cell receptor overstimulation, immunosuppressive cytokines (eg, transforming growth factor β), and hypoxia. While the mechanisms of T-cell exhaustion have been extensively studied in CD8+ T cells in vivo, the lack of a murine Vγ9Vδ2 subset complicates the investigation and generation of large numbers of exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. To address this limitation, we present a novel in vitro protocol for rapidly generating exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells through coculture with zoledronate-activated human tumor cells. We characterized the resulting cells using phenotypic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses comparing their profiles with published data on in vivo–exhausted T cells. Furthermore, we measured the reactivation potential of these exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells using anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies, demonstrating that CD3 stimulation can partially reverse exhaustion and restore antitumor effector functions. Furthermore, exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells retained some cytotoxic activity upon stimulation with TCEs, underscoring the versatility and applicability of our in vitro exhaustion model. This model offers a robust platform for the evaluation of novel immunotherapies targeting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, facilitating preclinical assessments before transitioning to in vivo studies.

Introduction

Gamma delta (γδ) T cells are promising candidates for novel immunotherapeutic strategies.1 Unlike conventional alpha beta (αβ) T cells, γδ T cells possess a distinct T-cell receptor (TCR) composed of γ and δ chains, allowing them to recognize a broad range of peptide and nonpeptide antigens in an major histocompatibility complex -independent manner.2,3 Bridging innate and adaptive immunity,4 γδ T cells respond rapidly to infection and stress signals, producing cytokines and exerting cytotoxic effects.5

In humans, γδ T cells are classified into Vδ1+, Vδ2+, and Vδ3+ subsets based on their TCR δ chain usage.6 Vδ2+ cells, which are predominantly found in peripheral blood, almost exclusively pair with the Vγ9 chain to form the Vγ9Vδ2 subset, whereas Vδ1 and Vδ3 cells are more abundant in mucosal tissues and liver, respectively.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are nonalloreactive and highly conserved. Their activation occurs via the TCR/CD3 complex in response to phosphoantigens (pAgs) like isopentenyl pyrophosphate, which accumulate during dysregulated mevalonate metabolism in tumor or infected cells. This recognition is mediated by butyrophilin (BTN) molecules, notably BTN3A1 and BTN2A1, which sense intracellular pAgs and trigger TCR signaling.7-9

These cells can kill both hematological and solid tumor cells through perforin/granzyme pathways and proinflammatory cytokine release (eg, interferon-γ [IFN-γ] and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]).10 Their broad antitumor reactivity has led to the development of targeted therapies, including T-cell engagers (TCEs), which are bispecific antibodies that simultaneously bind T cells (often via CD3) and tumor-associated antigens to promote immune synapse formation and tumor lysis.11 In this study, we evaluate novel camelid-derived TCEs targeting CD3, Vγ9, or Vδ2 chains, combined with CEACAM5, a tumor-associated antigen.12

Despite the therapeutic promise of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, their efficacy can be severely impaired by exhaustion, that is a dysfunctional state driven by chronic stimulation and the tumor microenvironment.13 Exhausted T cells exhibit reduced effector function, metabolic imbalance, and expression of inhibitory receptors like T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin containing protein-3 (TIM-3), T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) domains (TIGIT), and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3).14

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have been identified in various cancers15-18 and investigated in nonhuman primate models.19 Although exhaustion has been extensively characterized in CD8+ αβ T cells, recent work emphasizes that hypofunctional T-cell states encompass a spectrum, including tolerization, anergy, senescence, and metabolic dysfunction.20 Our understanding of exhaustion in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells remains limited, and the absence of this subset in mice complicates in vivo modeling.21 Moreover, no robust in vitro model currently exists to induce and study exhaustion in human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells.

In this study, we present a reproducible in vitro protocol to generate exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells through coculture with Zoledronate (Zol) treated SKOV3 tumor cells. We characterize their phenotypic, transcriptomic, and metabolic profiles, assess their reactivation using anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies, and evaluate their residual cytotoxicity through bispecific TCEs. This model provides a versatile tool for preclinical immunotherapy development targeting exhausted γδ T cells.

Materials and methods

T-cell engager molecules

Variable domain of the heavy-chain antibody (VHH) sequences targeting TCRγδ and CD3 were cloned from patented sequences into vectors and expressed in HEK293-F cells. Constructs were purified by nickel-affinity chromatography.

Immunophenotyping

Expanded Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were characterized by flow cytometry using markers including Vδ2, CD3, CD4, CD8, and exhaustion markers (programmed cell death protein 1 [PD-1], TIGIT, TIM-3, LAG-3). Transcription factors thymocyte selection-associated high mobilitygroup box protein (TOX) and c-musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (c-Maf) were detected after fixation.

Cell culture

Human ovarian (SKOV-3) and colon carcinoma (LS174T) lines were cultured in Dulbecco (or Dulbecco’s) modified Eagle medium with supplements. Epstein-Barr virus transformed B-cell lymphoblastoid lines were grown in RPMI1640 medium with supplements.

T-cell expansion

T cells from healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (EFS Nantes; consent CPDL-PLER-2022 029) were isolated and expanded: Vγ9Vδ2 cells with zoledronic acid or BrHPP plus interleukin-2 (IL-2) and αβ T cells with CD3/CD28 activation. Purity was verified by flow cytometry.

Exhaustion model

SKOV3 cells were pretreated with Zol, then cocultured with T cells for 4 days. Exhausted αβ T cells were generated by extended CD3/CD28 stimulation.

Functional assays

Degranulation was assessed by CD107a mobilization and cytokine release (IFN-γ and TNF-α) quantified by bead-based flow cytometry. Calcium influx measured by Fura-2 fluorescence microscopy after anti-CD3 stimulation.

Cytotoxicity

LS174 T cells, pretreated or not, were cocultured with T cells and bispecific antibodies and tumor lysis was tracked by green fluorescent protein signal loss using live-cell imaging over 96 hours.

Metabolic profiling

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured by Seahorse analyzer under various mitochondrial and T-cell activation conditions.

Transcriptomics

RNA from sorted live HER2- Vγ9Vδ2 or αβ T cells was extracted and sequenced. Reads were quality filtered, aligned, and analyzed for differential gene expression using DESeq2. Significant genes (P < .05) were used for pathway analysis via Metascape.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Two-way analysis of variance and unpaired t tests determined significance, with P < .05 considered significant. Additional experimental details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells cocultured with Zol-treated SKOV3 cells display an exhausted phenotype

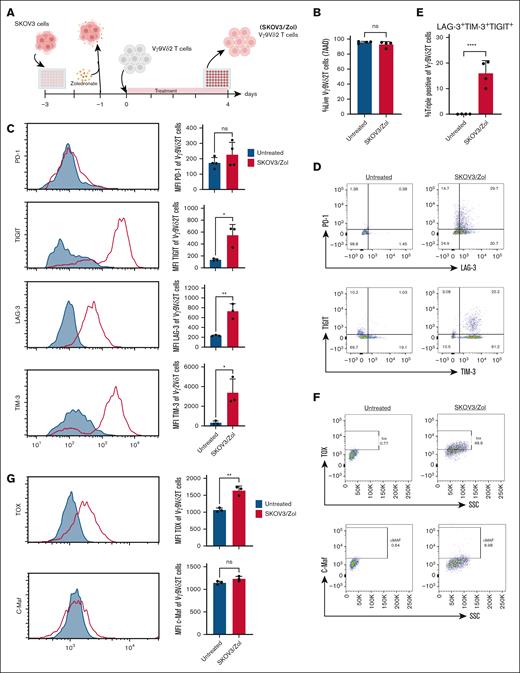

Exhaustion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells has not been extensively studied in vivo because of their absence in murine tissues, and a definitive in vitro phenotype remains undefined. In our study, human ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells were presensitized with Zol overnight and cocultured with ex vivo expanded Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in low-IL-2 (30 IU/mL) medium for 4 days (Figure 1A). Zol, an aminobisphosphonate, inhibits a key enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, promoting pAgs accumulation and subsequent Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell activation.23,24 The 4-day time point was based on previous natural killer cell exhaustion models with HEPG2 cells. Treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were then assessed for viability and checkpoint inhibitor expression via flow cytometry.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells treated with SKOV3/Zol show an exhausted phenotype. (A) Scheme of the 4 days coculture in vitro experiment between ex vivo expanded human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and Zol-presensitized SKOV3 cells. (B) Analysis by flow cytometry of expression of viability marker (7AAD) on ex vivo–expanded human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells before (blue) and after (red) treatment; n> 4 donors. (C) Flow cytometry histogram and mean fluorescence intensity analysis of expression of PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and TIGIT; n = 4 donors. (D) Dot plots from a representative donor of surface expression of PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and TIGIT. (E) Calculated percentage of LAG-3 TIM-3 TIGIT triple positive human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (F) Dot plots from a representative donor of intracellular expression of TOX and c-Maf transcription factors. (G) Flow cytometry histogram and mean fluorescence intensity analysis of expression of TOX and c-Maf; n = 3 donors. All statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t tests (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001).

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells treated with SKOV3/Zol show an exhausted phenotype. (A) Scheme of the 4 days coculture in vitro experiment between ex vivo expanded human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and Zol-presensitized SKOV3 cells. (B) Analysis by flow cytometry of expression of viability marker (7AAD) on ex vivo–expanded human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells before (blue) and after (red) treatment; n> 4 donors. (C) Flow cytometry histogram and mean fluorescence intensity analysis of expression of PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and TIGIT; n = 4 donors. (D) Dot plots from a representative donor of surface expression of PD-1, LAG-3, TIM-3 and TIGIT. (E) Calculated percentage of LAG-3 TIM-3 TIGIT triple positive human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (F) Dot plots from a representative donor of intracellular expression of TOX and c-Maf transcription factors. (G) Flow cytometry histogram and mean fluorescence intensity analysis of expression of TOX and c-Maf; n = 3 donors. All statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t tests (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001).

These cells maintained high viability (95%-99%) (Figure 1B). Exhaustion markers TIM-3, LAG-3, TIGIT, and PD-1 are well-established in T cells.25 Here, treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells showed increased TIM-3, TIGIT, and LAG-3 expression (3-12–fold mean fluorescence intensity increase; Figure 1C-D). PD-1 levels remained unchanged. About 15% of treated cells coexpressed all 3 markers, indicating deeper exhaustion (Figure 1E).

To benchmark against classical exhaustion, αβ T cells were cultured with anti-CD3/CD28 in low IL-2, or with SKOV3 cells (which they do not naturally recognize), in the same medium.26 In contrast, αβ T cells cultured with SKOV3 cells under the same conditions did not upregulate exhaustion markers, whereas classical exhaustion induced by prolonged anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation led to a marked increase in PD-1, LAG-3, TIGIT, TIM-3, and c-Maf expression, but not TOX (supplemental Figure 2).

TOX, a key transcription factor in exhaustion,27 was upregulated by 50% in treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, while c-Maf expression remained unchanged (Figure 1F-G).28

These findings suggest that SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells acquire an exhausted phenotype in vitro, warranting further investigation.

Decrease in effector functions and altered metabolism of in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells

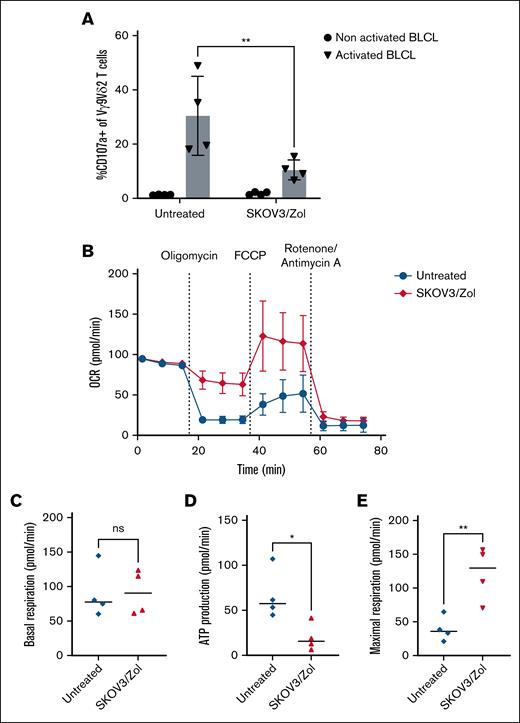

The degranulation activity of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells against Zol-presensitized Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells was assessed via CD107a expression assays (Figure 2A). The data revealed that CD107a expression levels were reduced by 50% following SKOV3/Zol treatment.

Decreased effector functions and altered metabolic profile of in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (A) Frequency (%) of CD107a among treated (right) vs untreated (left) Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells after coculture with Zol-presensitized (triangle) or nonactivated (round) BLCL. Effector-to-target ratio ratio (E:T) 1:1. (B) Monitoring of mitochondrial OCR, picomoles per minute of treated (red) vs untreated (blue) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after a mitostress experiment over time. (C) Basal respiration (picomoles per minute) measured as the mean of the 3 values in the absence of substrate. (D) ATP production (picomoles per minute) calculated as the difference between the maximum value after injection of oligomycin and the basal respiration. (E) Maximal respiration (picomoles per minute) measured as the maximum value after FCCP injection; n = 4 donors. All statistical analyses were performed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (panel A) or unpaired t tests (panels C-E) (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). BLCL, B-lymphoblastoid cell line.

Decreased effector functions and altered metabolic profile of in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (A) Frequency (%) of CD107a among treated (right) vs untreated (left) Vγ9Vδ2+ T cells after coculture with Zol-presensitized (triangle) or nonactivated (round) BLCL. Effector-to-target ratio ratio (E:T) 1:1. (B) Monitoring of mitochondrial OCR, picomoles per minute of treated (red) vs untreated (blue) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after a mitostress experiment over time. (C) Basal respiration (picomoles per minute) measured as the mean of the 3 values in the absence of substrate. (D) ATP production (picomoles per minute) calculated as the difference between the maximum value after injection of oligomycin and the basal respiration. (E) Maximal respiration (picomoles per minute) measured as the maximum value after FCCP injection; n = 4 donors. All statistical analyses were performed using 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (panel A) or unpaired t tests (panels C-E) (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). BLCL, B-lymphoblastoid cell line.

To further characterize our model, we measured the metabolic activity of exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Mitochondrial respiration was directly quantified through real-time live cell analysis using the Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer during a Cell Mitostress test. This test provides a detailed profile of mitochondrial activity through the injection of oligomycin (to inhibit adenosine triphosphate [ATP] synthase), FCCP (to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation and reveal maximal respiration), and rotenone/antimycin A (to inhibit complex I and III, measuring nonmitochondrial respiration). We show that the overall respiratory metabolism of the exhausted cells is altered (Figure 2B). Indeed, if the basal respiration of the treated cells is comparable to untreated conditions (Figure 2C), the ATP production, measured by the drop in OCR after oligomycin injection, is 30% lower for exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Figure 2D). However, the maximum respiration of these cells is 2.5 times higher than the untreated condition (Figure 2E). In conclusion, our data highlights that exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells exhibit altered metabolic activity, characterized by reduced ATP production and increased maximum respiration, indicating an intense but inefficient cellular activation. As a control, the same assays were conducted on αβ T cells, as presented in supplemental Figure 2. In these assays, SKOV3-treated αβ T cells showed lower basal respiration and ATP production compared with untreated cells, whereas their maximal respiration remained unchanged; in contrast, αβ T cells subjected to prolonged CD3/CD28 stimulation exhibited a profoundly suppressed metabolic profile, with minimal basal respiration and no response to mitochondrial stressors, a profile distinct from that observed in exhausted γδ T cells.

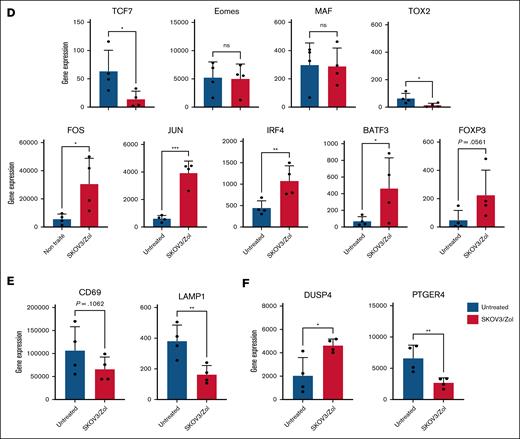

Exhaustion affects Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell transcriptome and key transcription factor expression

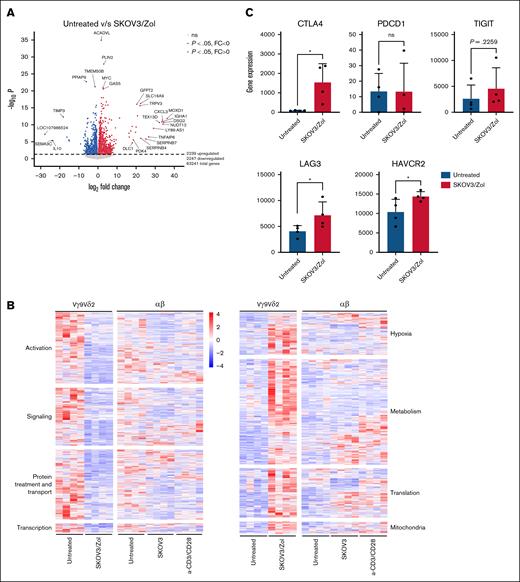

We then performed single cell RNA sequence analysis of untreated and SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, revealing substantial transcriptomic changes in treated versus untreated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells: 2239 genes were upregulated and 2247 downregulated (P < .05) (Figure 3A). Upregulated pathways included metabolism, contrasting with αβ T cells under anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, which showed stable or reduced glycolysis-related gene expression. Key glycolytic genes such as HK2, PFKFB3, GAPDH, LDHA, and ENO1 were upregulated in exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (see supplemental Figure 5).

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells show an altered transcriptome. (A) Volcano plot representing overexpressed (red) and underexpressed (blue) genes, identified as the threshold of log twofold change >1 and P value <.05, comparing untreated to SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (B) Heatmaps representing the selected -Log 10 (P > 10) genes expression, grouped by hand by major pathway for untreated and SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, untreated, SKOV3-treated and anti-CD3/CD28 -treated αβ T cells. (C-F) Diverse genes of interest expression, as a gene read count, between untreated (blue) and SKOV3/Zol-treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. All statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, exact P values are written where a trend was observed).

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells show an altered transcriptome. (A) Volcano plot representing overexpressed (red) and underexpressed (blue) genes, identified as the threshold of log twofold change >1 and P value <.05, comparing untreated to SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (B) Heatmaps representing the selected -Log 10 (P > 10) genes expression, grouped by hand by major pathway for untreated and SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, untreated, SKOV3-treated and anti-CD3/CD28 -treated αβ T cells. (C-F) Diverse genes of interest expression, as a gene read count, between untreated (blue) and SKOV3/Zol-treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. All statistical analyses were performed using unpaired t tests (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001, exact P values are written where a trend was observed).

Treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells also showed downregulation in activation-related genes (Figure 3B), consistent with exhaustion. This profile mirrors classical αβ T-cell exhaustion29 but differs mechanistically because of SKOV3 and pAgs stimuli. Hypoxia-related genes were also upregulated, implicating hypoxia in the exhaustion process.

Metabolic, translational, and mitochondrial gene expression was increased under SKOV3/Zol treatment. Exhaustion-associated markers, such as CTLA4, and LAG3 were significantly upregulated. TIGIT and HAVCR2 (TIM-3) showed an upward trend that did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3C), whereas PDCD1 (PD-1) remained low. TCF7 was significantly downregulated, and FOXP3 upregulated, indicating a shift toward a regulatory phenotype. Eomesodermin (EOMES), TOX2 (TOX), and MAF (c-Maf) expression remained stable, aligning with protein levels (Figures 1G and 3D).

LAMP1 expression significantly declined by 40% to 60%, when CD69 showed a nonsignificant reduction of expression, reflecting impaired activation and degranulation (Figure 3E). FOS and JUN, components of activator protein-1 (AP-1) critical for T-cell responses, were upregulated (Figure 3D). IRF4 and BATF3, both associated with exhaustion, were elevated. DUSP4, a MAPK pathway inhibitor, was upregulated in both T cell types under SKOV3 conditions, potentially contributing to FOS/JUN upregulation (Figure 3F). PTGER4, linked to T-cell activation, was downregulated in SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, confirming their exhausted state.

Control analyses for αβ T cells are provided in supplemental Figure 3. Overall, SKOV3/Zol-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and CD3/CD28-exhausted αβ T cells display overlapping exhaustion signatures, with distinct regulatory adaptations.

To validate our model, we compared our transcriptomic data with published datasets on tumor-infiltrating γδ T cells. In breast cancer, Boufea et al30 reported γδ T-cell subsets that were highly activated yet immunosuppressed, a pattern we similarly observed with concurrent cytotoxic gene expression and inhibitory receptor upregulation. In kidney cancer, Rancan et al31 identified exhausted Vδ2− γδ T cells with downregulated TCF7 and increased TIGIT and TIM-3, while retaining cytotoxicity. Our model reproduced these features, supporting that SKOV3/Zol-expanded Vγ9Vδ2 T cells mirror viable but hypofunctional tumor-infiltrated γδ T cells. Our results highlight distinct transcriptomic and functional exhaustion mechanisms between Vγ9Vδ2 and αβ T cells. In Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, metabolic dysregulation—especially glycolysis—drives exhaustion, while αβ T cells follow canonical inhibitory pathways. Taken together with previous transcriptomic studies of tumor-infiltrating γδ T cells,30,31 our data indicate that the SKOV3/Zol-induced model mirrors key features of tumor-infiltrated γδ T cells that remain viable but exhibit impaired functionality.

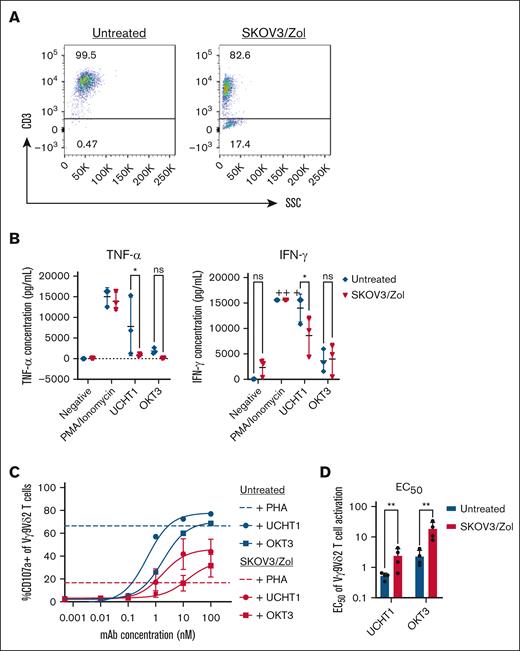

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells show diminished effector functions to anti-CD3 stimulation

To assess the capacity of in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to regain functionality, we analyzed their effector responses through CD107a expression assays and cytokine production following anti-CD3 stimulation, using soluble anti-CD3ε monoclonal antibodies (UCHT1 and OKT3). Given that diminished effector function is often linked to reduced TCR expression, we first confirmed that the exhausted T cells maintained surface CD3 expression. Flow cytometry revealed that over 80% of these cells remained CD3+ (Figure 4A), affirming their ability to interact with anti-CD3 antibodies.

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have reduced effector functions. (A) Dot plots from a representative donor of surface expression of CD3. (B) Minimal previsions of TNF-α and IFN-γ cytokines after PMA/ionomycin (control), UCHT1 or OKT3 stimulation by untreated (blue) or treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (C) Frequency (%) of CD107a among treated (red) vs untreated (blue) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after increasing concentrations of anti-CD3 mAb UCHT1 (round) or OKT3 (square). Positive control: PHA (10 ng/mL). n = 4. (D) Quantification of the UCHT1 or OKT3 mAb concentration (nanomolar) allowing to produce 50% of the maximal observed reactivation of untreated (blue) vs treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. n > 3. All statistical analysis were performed using 2-way ANOVA (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). mAb, monoclonal antibody; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; SSC, side scatter.

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have reduced effector functions. (A) Dot plots from a representative donor of surface expression of CD3. (B) Minimal previsions of TNF-α and IFN-γ cytokines after PMA/ionomycin (control), UCHT1 or OKT3 stimulation by untreated (blue) or treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (C) Frequency (%) of CD107a among treated (red) vs untreated (blue) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after increasing concentrations of anti-CD3 mAb UCHT1 (round) or OKT3 (square). Positive control: PHA (10 ng/mL). n = 4. (D) Quantification of the UCHT1 or OKT3 mAb concentration (nanomolar) allowing to produce 50% of the maximal observed reactivation of untreated (blue) vs treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. n > 3. All statistical analysis were performed using 2-way ANOVA (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). mAb, monoclonal antibody; PHA, phytohemagglutinin; SSC, side scatter.

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells displayed a marked reduction in proinflammatory cytokine release. Specifically, UCHT1 stimulation resulted in significant loss of IFN-γ and TNF-α production (P = .0237 and .0140, respectively) (Figure 4B). Notably, while exhausted cells were unable to produce TNF-α, they retained some capacity to secrete IFN-γ upon CD3 engagement, albeit at reduced levels compared with nonexhausted cells.

Parallelly, we tested the nonspecific activation potential of exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells using phytohemagglutinin.

This strong mitogenic stimulus reduced CD107a expression by ∼50% (Figure 4C), underscoring a generalized decline in effector functionality in these populations. Moreover, a substantial reduction in effector functions was observed following stimulation with both UCHT1 and OKT3. However, upon UCHT1 stimulation, half maximal effective concentration (EC50) values) of the exhausted cells were significantly higher than those of untreated cells, suggesting that while the TCR signaling machinery remained functional, its sensitivity is reduced in the exhausted state (Figure 4D).

In summary, our findings indicate that although in vitro-generated exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells exhibit a profound loss of TNF-α production and reduced degranulation capacity, they retain the ability to secrete IFN-γ upon anti-CD3 stimulation.

This partial functional preservation highlights a potential avenue for reinvigorating exhausted T cells in therapeutic contexts. As a control, similar assays were conducted on αβ T cells, as presented in supplemental Figure 4. SKOV3-treated αβ T cells retained CD107a responses, unlike CD3/CD28-exhausted αβ T cells, which lost CD107a expression upon activation.

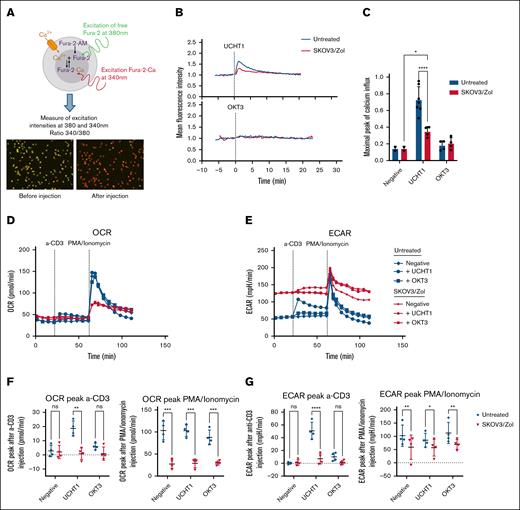

Exhaustion alters Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell calcium influx and metabolism upon CD3 stimulation

To further investigate the reactivation capacity of exhausted cells upon CD3 stimulation, we studied into more detail the very early events induced after Vγ9Vδ2 TCR engagement. Considering that the concentration of intracellular free calcium (Ca2+) is rapidly increased upon T-cell activation by triggering of the TCR/CD3 complex, we analyzed at the single cell level the kinetics and intensity of Ca2+ responses in CD3-stimulated exhausted and nonexhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells by video microscopy (Figure 5A). In untreated conditions, UCHT1 stimulation triggers a swift and strong Ca2+ response within seconds after injection of the monoclonal antibody (Figure 5B). Similarly, UCHT1 induces a short but ∼50% reduced Ca2+ response within exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, however the response remains significantly higher than if no stimuli were to be injected (Figure 5C). On the other hand, as already seen before,32 OKT3 does not seem to induce any Ca2+ influx in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, both in untreated and in exhausted cells. Ca2+ influx of SKOV3-treated αβ T cells was similar to untreated, while CD3/CD28-exhausted αβ T cells showed a reduced Ca2+ response upon OKT3 and UCHT1 stimulation (supplemental Figure 4).

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have reduced calcium influx and altered metabolism upon CD3 stimulation. (A) Sketch of the calcium influx video-microscopy principle and images recreated before and after UCHT1 injection. (B) Calcium influx measured by video-microscopy of untreated (blue) vs treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells upon anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) UCHT1 and OKT3 injection over time. (C) Calculated peaks of calcium influx after anti-CD3 mAb injection. (D-E) Monitoring of mitochondrial OCR and ECAR at resting state, after anti-CD3 and PMA-ionomycin injection. (F-G) OCR (F) and ECAR (G) peaks calculated as the difference between the values before and after anti-CD3 or PMA-ionomycin injection; n = 4 donors. All statistical analysis were performed using 2-way ANOVA (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001).

In vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have reduced calcium influx and altered metabolism upon CD3 stimulation. (A) Sketch of the calcium influx video-microscopy principle and images recreated before and after UCHT1 injection. (B) Calcium influx measured by video-microscopy of untreated (blue) vs treated (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells upon anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) UCHT1 and OKT3 injection over time. (C) Calculated peaks of calcium influx after anti-CD3 mAb injection. (D-E) Monitoring of mitochondrial OCR and ECAR at resting state, after anti-CD3 and PMA-ionomycin injection. (F-G) OCR (F) and ECAR (G) peaks calculated as the difference between the values before and after anti-CD3 or PMA-ionomycin injection; n = 4 donors. All statistical analysis were performed using 2-way ANOVA (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001).

To explore how exhaustion impacts the metabolic response to CD3 stimulation, both untreated and exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were analyzed following specific (UCHT1 and OKT3) or nonspecific (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA]/ionomycin) activation. Under resting conditions, exhausted cells displayed similar OCR (Figure 5D) but exhibited a threefold higher ECAR (Figure 5E) compared to untreated cells.

As anticipated, robust nonspecific activation with PMA/ionomycin resulted in a 50% to 75% diminution of OCR and ECAR peaks in exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Figure 5F) In untreated cells, UCHT1 stimulation elicited a stronger increase in OCR and ECAR metabolic activities compared to OKT3. However, in exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, no detectable increase in oxygen consumption was observed upon stimulation with either CD3 antibody (Figure 5F). In addition, the ECAR peak in exhausted cells was reduced by more than 50% following UCHT1 stimulation and was absent after OKT3 stimulation (Figure 5G).

SKOV3-treated αβ T cells showed reduced basal respiration and OCR responses but retained ECAR levels, whereas CD3/CD28-exhausted αβ T cells had severely impaired metabolism (supplemental Figure 4).

These findings collectively demonstrate that exhaustion profoundly disrupts early activation processes and metabolic functions in human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, leading to reduced Ca2+ influx, mitochondrial respiration, and glycolytic activity. Despite these impairments, exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells retain some ability to induce Ca2+ influx and glycolysis in response to UCHT1-specific activation.

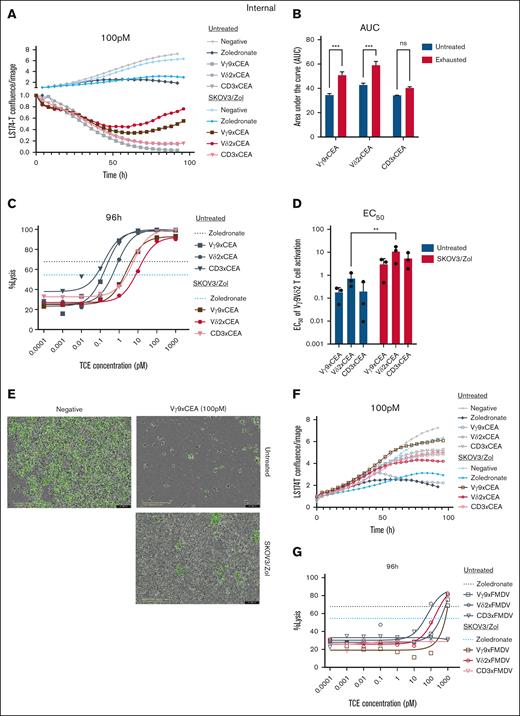

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are activated by bsFabs in the presence of CEA-expressing tumor cells

The in vitro exhaustion model of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was utilized to assess the effectiveness of anti-Vδ2, Vγ9 and CD3×CEACAM5 (shortened CEA) bispecific antibodies.12 Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were compared with untreated cells for their ability to lyse GFP+ tumor cells under increasing concentrations of TCEs. Tumor cell lysis was measured every 4 hours over a 4-day coculture period.

The results demonstrated that the tested TCEs significantly reduce tumor cell numbers. Zol presensitization stabilizes tumor growth but does not cause a significant reduction like the TCEs (Figure 6A). Control foot and mouth disease (FMDV) compounds show weak or comparable tumor lysis to the Zol control (Figure 6B). High concentrations of anti-Vδ2×FMDV and Vγ9×FMDV TCEs enhance cytotoxicity, suggesting that the T cells exhibit some cytotoxicity with anti-TCR alone, but this is not seen with anti-CD3 × FMDV (Figure 6D).

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are activated by bsFabs in the presence of CEA-expressing tumor cells. LS174-T cells are cocultured with exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (E:T ratio 5 :1) and Vγ9 (square), Vδ2 (round) or CD3 (triangle) x CEA (plain) or control FMDV (empty) TCEs. (A-F) Measure of the LS174-T cell confluence by green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence intensity every 4 hour during 96 hour over the confluence at t = 0. Negative control is a coculture between Vγ9Vδ2 T and LS174-T cells without TCE (gray and light blue), Zol control is a coculture of presensitized LS174-T with Zol before contact with Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (black and blue). TCEs are at a 0.1-nM concentration. (B,D) Quantification of the Vγ9xCEA, Vδ2xCEA or CD3xCEA TCE concentration (nanomolar) allowing to produce 50% of the maximal observed reactivation (D) and the total reactivation over time expressed as the integrated response area under the curve (AUC) (B) of untreated (blue) or exhausted (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (C,G) Tumoral lysis percentage calculated after 96-hour coculture as the disappearance of GFP fluorescence at time t over GFP fluorescence at time t = 0. TCE concentration from 0.1 fM to 1 nM. (E) Image (Incucyte; scale, 400 μm) representing the LS174-T-GFP confluence without TCE (negative) or with Vγ9 × CEA (0.1 nM), untreated or exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. n = 3 donors. All statistical analyses were performed using 2-way ANOVA on either AUC (panels A-B) or calculated EC50 values (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). ns, not significant.

Exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are activated by bsFabs in the presence of CEA-expressing tumor cells. LS174-T cells are cocultured with exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (E:T ratio 5 :1) and Vγ9 (square), Vδ2 (round) or CD3 (triangle) x CEA (plain) or control FMDV (empty) TCEs. (A-F) Measure of the LS174-T cell confluence by green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence intensity every 4 hour during 96 hour over the confluence at t = 0. Negative control is a coculture between Vγ9Vδ2 T and LS174-T cells without TCE (gray and light blue), Zol control is a coculture of presensitized LS174-T with Zol before contact with Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (black and blue). TCEs are at a 0.1-nM concentration. (B,D) Quantification of the Vγ9xCEA, Vδ2xCEA or CD3xCEA TCE concentration (nanomolar) allowing to produce 50% of the maximal observed reactivation (D) and the total reactivation over time expressed as the integrated response area under the curve (AUC) (B) of untreated (blue) or exhausted (red) Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (C,G) Tumoral lysis percentage calculated after 96-hour coculture as the disappearance of GFP fluorescence at time t over GFP fluorescence at time t = 0. TCE concentration from 0.1 fM to 1 nM. (E) Image (Incucyte; scale, 400 μm) representing the LS174-T-GFP confluence without TCE (negative) or with Vγ9 × CEA (0.1 nM), untreated or exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. n = 3 donors. All statistical analyses were performed using 2-way ANOVA on either AUC (panels A-B) or calculated EC50 values (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .003; ∗∗∗P < .0005; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). ns, not significant.

SKOV3/Zol-exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 cells show a moderate reduction (∼10%) in tumor lysis ability in the presence of the different TCEs (Figure 6C). These cells cannot fully control tumor growth with anti-Vδ2×CEA and Vγ9×CEA, and tumor proliferation resumes after 72 hours of coculture, while this does not occur with anti-CD3 × CEA (Figure 6A). Even at high concentrations of anti-Vγ9×CEA, exhausted cells cannot fully eliminate tumor cells (Figure 6E). Furthermore, the EC50 values for all tested TCEs are higher in exhausted cells compared to untreated cells, indicating reduced efficacy (Figure 6F). The most promising candidates for reinvigorating exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, with the smallest increase in EC50, are anti-Vγ9×CEA and anti-CD3 × CEA TCEs.

Despite the exhaustion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, TCEs demonstrated superior efficacy in inducing tumor cell lysis compared to Zol presensitization. Whereas Zol primarily suppressed tumor cell proliferation, TCE-stimulated exhausted Vγ9Vδ2T cells effectively reduced the tumor cell population to a significant extent.

In conclusion, this model offers a valuable platform for evaluating the potency and effectiveness of novel immunotherapeutic agents targeting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in vitro, providing critical insights prior to clinical development.

Discussion

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells play a key role in antitumor immunity through TCR-dependent but HLA-independent recognition of tumor cells.1 They eliminate tumors mainly via proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IFN-γ and cytolytic molecules such as perforin and granzyme. Their unique properties associated to a low alloreactivity make them promising candidates for efficient immunotherapies with reduced side effects. In this context, bispecific antibodies like TCEs can precisely target Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, including those against CD3, Vγ9 or Vδ2 chains, and the tumor-associated antigen CEACAM5.12

To investigate how these therapeutic functions may be impaired, we developed and characterized an in vitro model of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell exhaustion by coculturing them with SKOV3 cells pretreated with Zol. Although SKOV3 cells are not naturally recognized by αβ or γδ T cells, Zol treatment promotes pAgs accumulation, enabling TCR-dependent recognition by Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. This protocol preserved Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell viability, mimicking tumor-infiltrating effector cells that are viable but hypofunctional.

Phenotypically, treated cells overexpressed exhaustion markers TIM-3, TIGIT, and LAG-3, while TCF7 was downregulated, indicating advanced exhaustion and a shift toward a regulatory phenotype. The coexpression of these markers suggests a deeper exhaustion, although their expression levels may vary depending on the cancer context.22,33

In functional assays, exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells still secreted IFN-γ and TNF-α upon PMA/ionomycin stimulation, which bypasses TCR signaling. However, their metabolic response was markedly reduced, with lower ECAR and OCR increases compared to controls, highlighting impaired activation-associated metabolic reprogramming. This suggests that exhaustion involves both surface receptor dysfunction and intrinsic metabolic defects.

Interestingly, PD-1 was not upregulated, consistent with models of in vitro CD8+ αβ T-cell exhaustion,29,34 and recent findings implying PD-1 may indicate γδ T-cell activation rather than exhaustion.35,36 PD-1 upregulation may only occur in more advanced stages, which are not captured by this intermediate model.

Treated cells also showed high intracellular TOX, a key exhaustion marker,27,37 but only slight upregulation of c-Maf, suggesting c-Maf may be unreliable for in vitro γδ T-cell exhaustion. These cells exhibited impaired function, reduced IFN-γ secretion, and complete TNF-α loss—hallmarks of intermediate exhaustion.38 LAMP1 and CD69 expression was diminished, reflecting reduced activation. Unlike terminally exhausted CD8+ αβ T cells,38 Vγ9Vδ2 T cells retained surface CD3 expression, indicating a nonterminal exhaustion stage, consistent with the concept that T-cell hypofunctional states are diverse and context dependent.20 Because SKOV3 cells lack TGF-β secretion,39 exhaustion in this system appears driven by TCR overstimulation from pAg recognition rather than TGF-β-mediated signaling. Transcriptomic and metabolic analyses further revealed that exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells have a distinct profile from αβ T cells, with upregulated metabolic and hypoxia-related pathways and sustained glycolytic and respiratory activity despite dysfunction. Unlike the quiescent state of exhausted αβ T cells, this mirrors tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in hypoxic, nutrient-poor environments.10,40,41 Notably, our data also reveal a divergence in basal glycolytic activity: while in vitro–exhausted CD8+ αβ T cells display profoundly suppressed glycolysis, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells retain elevated basal glycolytic rates despite functional impairment. Thus, exhaustion manifests through subset-specific metabolic programs, with γδ T cells maintaining a metabolically active yet dysfunctional state, in contrast to the quiescent profile of αβ T cells.

Metabolically, SKOV3/Zol-treated cells exhibited high glycolysis and maximal respiration, dissimilar to CD8+ T cells40 but resembling tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.42 Despite their metabolic activity, they failed to generate ATP or upregulate metabolism upon stimulation, operating in a high-energy, dysfunctional state. Chronic pAg exposure, IL-2 deprivation, or hypoxia may drive this dysfunction. Transcriptomic data supports this, showing upregulation of metabolic pathways and downregulation of activation-related genes in treated cells. Hypoxia-related genes were also elevated, suggesting hypoxia contributes to exhaustion. Markers like Eomes and c-Maf remained unchanged, underscoring a partial exhaustion phenotype. FOS and JUN were upregulated, reflecting increased transcriptional activity despite impaired function.

Our in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells’ transcriptomic profile closely matches tumor-infiltrating hypofunctional γδ T cells from recent RNA-sequencing studies,30,31 supporting our model’s translational relevance. Functionally, these cells showed reduced degranulation and cytokine secretion, with marked TNF-α loss but partial IFN-γ retention. They maintained surface CD3 and could be partially reactivated by anti-CD3, indicating an intermediate exhaustion state that may allow therapeutic rescue.

These findings highlight distinct exhaustion mechanisms in Vγ9Vδ2 vs αβ T cells, with metabolic dysregulation and altered gene expression dominating in γδ T cells. Discrepancies between messenger RNA and protein expression for markers like TOX and TCF1/7 suggest posttranscriptional or epigenetic regulation, further emphasizing the need for integrative epigenetic analyses.22,43

Our model fills a key gap, as robust platforms for human Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell exhaustion are lacking.44 Because we used an expansion protocol similar to the one currently applied in adoptive transfer approaches of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells,45,46 our platform also reflects conditions that are directly relevant for therapeutic applications. Although using previously expanded T cells means a baseline activation, our exhaustion protocol induced significant additional phenotypic and functional changes. Still, our in vitro system cannot fully capture patient exhaustion heterogeneity shaped by tumor type, microenvironment, and disease stage, and lacks some microenvironmental cues that may limit translational fidelity.

We tested several TCEs known to stimulate healthy cells12 on exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. All induced cytotoxicity, but tumor regrowth occurred after 72 hours with anti-Vγ9xCEA and anti-Vδ2xCEA. Activation with anti-CD3 × CEA induced stronger cytotoxic responses in both untreated and exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells than Vγ9xCEA or Vδ2 × CEA TCEs. Exhausted cells stimulated by anti-CD3 × CEA showed functional profiles similar to untreated controls, indicating CD3 activation can bypass exhaustion-related TCR signaling defects. This underscores the therapeutic potential of CD3-based engagers to restore function in exhausted cells.

These results inform next-generation immunotherapy design, highlighting benefits of combining TCEs with cytokines or checkpoint blockade to overcome exhaustion.47-50 Our model offers a platform to study molecular drivers of exhaustion, including hypoxia, metabolic stress, and epigenetic regulation.

Overall, our data show our exhaustion model of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells is TCR-dependent. In contrast, αβ T cells, activated via peptide-major histocompatibility complex, do not respond to SKOV3 cells and remain largely unaffected, indicating exhaustion is subset-specific and not a general tumor effect. Unlike terminal exhaustion from CD3/CD28 stimulation in αβ T cells, our SKOV3/Zol model induces an intermediate, potentially reversible exhaustion in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. This provides a rationale for immunotherapeutic reactivation via CD3 stimulation and supports the development of strategies tailored to the unique biology of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells.

Future work should compare in vitro–exhausted Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to patient tumor cells, explore epigenetic and posttranscriptional regulation, and assess microenvironmental impacts using advanced coculture or organoid models.22,51

In summary, the SKOV3/Zol model induces partial Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell exhaustion and offers a robust in vitro platform for early immunotherapy evaluation, without reliance on murine systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Cell and Tissue Imaging Center of the University of Nantes (MicroPICell) for imaging and the Cytocell Cytometry Center of Nantes for technical assistance. They thank the Automated Monoclonal Antibody Production and Protein Science and Technology teams of the Sanofi Large Molecule Research platform (Vitry, France) for the purification of the T-cell engagers. SeaHorse XF96 Analyzer was obtained with financial support from Institut Thématique MultiOrganisme (ITMO) Cancer of Aviesan within the framework of the 2021-2030 Cancer Control Strategy.

This work was financially supported by Sanofi (collaboration agreement Sanofi/Université de Nantes). M.C. was supported by a Conventions Industrielles de Formation par la Recherche (CIFRE) fellowship (No. 2021/1444) funded, in part, by the National Association for Research and Technology on behalf of the French Ministry of Education and Research, and, in part, by Sanofi.

Authorship

Contribution: E.S. and D.B. conceptualized and designed the project; M.C., J.L., E.S., and D.B. analyzed and interpreted the data; M.C., with inputs from J.L., C.H., and M.L.-B., generated and acquired data; M.C., E.S., and D.B. contributed to study methodology; M.C. and J.L. performed statistical analysis; M.C., E.S., and D.B., with inputs from J.L., M.L.-B., and C.P., wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.C. and D.B. are Sanofi employees and may hold shares and/or stock options in the company. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Emmanuel Scotet, INSERM, Unité Mixte de Recherche 1307, Institut de Recherche en Santé, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unité Mixte de Recherche 6075, 8 quai Moncousu, 44007 Nantes, France; email: Emmanuel.Scotet@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

Sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE303586).

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Emmanuel Scotet (emmanuel.scotet@inserm.com), on reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.