Key Points

Eight proteomic subtypes with distinct clinical and molecular properties were established, enriching the current classification of AML.

Age-associated protein profiles were identified, leading to the construction of a hematopoietic aging score with prognostic value.

Visual Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a highly heterogeneous hematological malignancy that increasingly affects the older population, with its posttranscriptional landscape remaining largely elusive. Establishing a stable proteomics-based classification system and systematically screening age-related proteins and regulatory networks are crucial for understanding the pathogenesis and outcomes of AML. In this study, we leveraged a multiomics cohort of 374 patients newly diagnosed with AML, integrating proteome, phosphoproteome, genome, transcriptome, and drug screening data. Through similarity network fusion clustering, we established 8 proteomic subtypes with distinct clinical and molecular properties, including S1 (CEBPA mutations), S3 (myelodysplasia-related AML), S4 (PML::RARA), S5 (NPM1 mutations), S6 (PML::RARA and RUNX1::RUNX1T1), S8 (CBFB::MYH11), S2 and S7 (mixed), aligning well with and adding actionable value to the latest World Health Organization nomenclature of AML. Hematopoietic lineage profiling of proteins indicated that megakaryocyte/platelet- and immune-related networks characterized distinct aging patterns in AML, which were consistent with our recent findings at the RNA level. Phosphosites also demonstrated distinct age-related features. The high protein abundance of megakaryocytic signatures was observed in S2, S3, and S7 subtypes, which were associated with advanced age and dismal prognosis of patients. A hematopoietic aging score with an independent prognostic value was established based on proteomic data, where higher scores correlated with myelodysplasia-related AML, NPM1 mutations, and clonal hematopoiesis-related gene mutations. Collectively, this study provides an overview of the molecular circuits and regulatory networks of AML during the aging process, advancing current classification systems and offering a comprehensive perspective on the disease.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological malignancy with high heterogeneity, particularly in older patients who often exhibit limited treatment responses and poor prognosis.1 According to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry data, patients aged >65 years account for 60.7% of all cases of AML and 75.9% of all deaths.2 To better understand the underlying biology of AML and improve clinical outcomes, it is essential to characterize the age-related molecular signatures. In recent years, advances in genomic and transcriptomic analyses have continuously improved the molecular classification and risk stratification of the disease.3-6 Emerging mass spectrometry (MS)-based technologies will provide a deeper insight into the biological features and pathogenesis of AML.7-15

In the hematopoietic system, age-related changes affect the number and function of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), manifesting as reduced self-renewal capacity, perturbed state of quiescence, and myeloid-skewed hematopoiesis.16,17 Biomarkers of hematopoietic aging include HSC-intrinsic mechanisms, such as proliferative stress, DNA damage, and dysregulated autophagy and proteostasis,18 as well as increased proinflammatory signaling in the bone marrow (BM) niche.19-21 Moreover, somatic mutations in genes associated with clonal hematopoiesis (CH), such as DNMT3A, ASXL1, and TET2, tend to accumulate in older individuals, which may contribute to the development of AML and its precursor diseases. These factors jointly lead to the molecular complexity and refractory nature of AML in older individuals.

We have established core transcriptomic subgroups of AML, enriching for distinct molecular biomarkers and networks, and identified inflammatory- and platelet (PLT)-related factors as one of the most striking age-associated signatures in AML.6,22 Previous proteomic studies in AML have identified several protein biomarkers and prognostic subtypes, as exemplified by the Mito-AML subtype.8-10,12,13 However, the hallmarks of hematopoietic aging at the proteome level have yet to be fully elucidated in AML. Also, technical difficulties and reproducibility issues have posed great challenges to proteomics research, while data from different research groups are difficult to integrate due to differences in the platforms and methodologies. It is imperative to produce more proteomic data sets, and to systematically evaluate the clinical significance of proteomic signatures in AML. Furthermore, correlations between proteomic subtypes and the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification require further investigation.8,14,23 These challenges motivate us to comprehensively characterize the proteomic subtyping and intricate mechanisms that link aging to AML in a large-scale cohort.

Through integrating proteomics and phosphoproteomics data with genomics, transcriptomics, and drug response measurements, this study aims to broaden the scope of previous AML classification systems and regulatory networks based on genomic and transcriptomic information into the protein dimension, and shed new light on how aging shapes the pathogenesis of AML, thereby enhancing our ability to comprehend and manage the disease more rationally in an aging society.

Methods

Patients and samples

A total of 374 patients newly diagnosed with AML were enrolled in this study. Proteomics (n = 374) and phosphoproteomics (n = 217) data were obtained from bone marrow mononuclear cells of patients using the 4-dimensional data-independent acquisition quantitative strategy.24 Among them, targeted or whole exome sequencing (n = 373) and RNA sequencing (n = 361) were also conducted. Treatment protocols, sample processing, and DNA and RNA sequencing were performed as previously reported.6,22

Establishment of proteomic subtypes

Unsupervised clustering of proteomics data was performed using similarity network fusion (SNF) analysis with the R package SNFtool (v.2.3.1). The SNF approach was chosen because it is based on networks of samples, which can efficiently extract valuable information even from a small sample size, and is robust to noise and data heterogeneity.25 Details concerning data processing and parameter setting are provided in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood website.

Identification of age-related protein/phosphosite patterns and clusters

To accommodate the heterogeneity of proteomic and phosphoproteomic data from various patients, we employed locally weighted regression models combined with an adaptive strategy to prevent overfitting.26 This approach effectively mitigated noise in the data, and benefited the exploration of trends in the abundance of proteins and phosphosites in the aging process. Subsequently, we used fuzzy c-means clustering analysis,27 guided by an elbow plot of the minimum centroid distances to determine the optimal number of clusters. This methodology enables the performance of unsupervised clustering of proteins and phosphosites based on their changing trends throughout the aging process.

Construction of the HAS

High-throughput drug screening

To investigate the drug sensitivity of patient samples, we selected 41 drugs and 39 drug combinations that have been approved for AML treatment or in the exploration of clinical trials (supplemental Data set 10). In vitro drug response assays were conducted using 102 samples, excluding acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Detailed information about the drug screening experiments and drug response analyses are provided in the supplemental Methods.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. All patients have given informed consent for both treatment and cryopreservation of BM and peripheral blood samples according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Overview of AML multiomics cohort

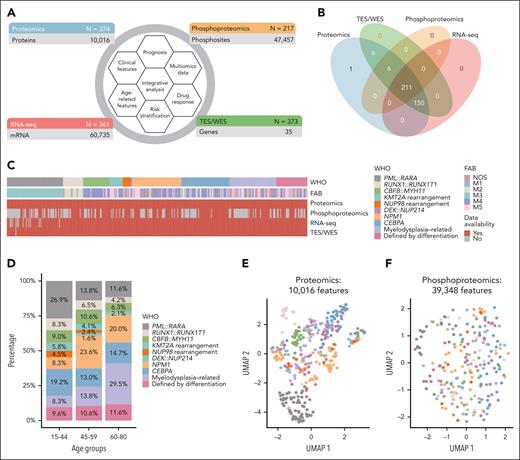

The overview of the study cohort and the detection of multiomics are depicted (Figure 1A-B). Notably, these cases spanned diverse cytogenetic and molecular subtypes, including APL, representing a wide spectrum of AML (Figure 1C). Clinical characteristics of all enrolled patients are summarized (Table 1; supplemental Data set 1). The age-related distribution of genetic abnormalities was consistent with our previous work.22 With the increase of age, the frequency of common gene fusions declined, while that of mutations associated with myelodysplasia-related AML (AML-MR) increased (Figure 1D). Both overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) of patients markedly deteriorated with age (supplemental Figure 1A-B). The workflow of the proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis is illustrated (supplemental Figure 2). Quality control of MS-based data demonstrated satisfactory results (supplemental Figure 3). The uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) analysis of 10 016 proteins showed distinct clusters aligning with common WHO-defined entities, particularly for PML::RARA, RUNX1::RUNX1T1, CBFB::MYH11, and CEBPA mutations, reflecting their distinct phenotypes and mutually exclusive nature at the proteome level (Figure 1E). The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding visualization of common AML subtypes was also performed (supplemental Figure 4). In contrast, the UMAP of 39 348 phosphosites did not exhibit a clear clustering pattern (Figure 1F).

Overview of the study cohort. (A) Schematic overview of multiomics data obtained from our cohort. TES and WES were performed on 362 and 11 AML samples, respectively. The analysis focuses on 35 genes that are most frequently mutated in AML. (B) Venn diagram depicting the number of samples within each data layer. (C) The French-American-British (FAB) subtyping, WHO classification, and multiomics information of 374 patients with AML. (D) The proportion of WHO-defined entities in different age groups. All patients were categorized into 3 age groups, namely, 15 to 44 years, 45 to 59 years, and 60 to 80 years. (E-F) UMAP of AML samples using 10 016 measured proteins (E) and 39 348 measured phosphosites (F), with colors denoting different WHO subtypes. (G) Gene set variation analysis scores for proteomics based on differentially regulated gene ontology (GO) pathways in WHO subtypes (left heat map). Spearman correlation coefficients of the proteome and the transcriptome for the annotated pathways are displayed (right heat map, asterisks mark significantly correlated pathways with P < .05, Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected). (H) Heat map depicting kinome profiling with z scores calculated by kinase-substrate enrichment analysis algorithm. GSVA, gene set variation analysis; NOS, not otherwise specified; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; TES, targeted exome sequencing; WES, whole exome sequencing.

Overview of the study cohort. (A) Schematic overview of multiomics data obtained from our cohort. TES and WES were performed on 362 and 11 AML samples, respectively. The analysis focuses on 35 genes that are most frequently mutated in AML. (B) Venn diagram depicting the number of samples within each data layer. (C) The French-American-British (FAB) subtyping, WHO classification, and multiomics information of 374 patients with AML. (D) The proportion of WHO-defined entities in different age groups. All patients were categorized into 3 age groups, namely, 15 to 44 years, 45 to 59 years, and 60 to 80 years. (E-F) UMAP of AML samples using 10 016 measured proteins (E) and 39 348 measured phosphosites (F), with colors denoting different WHO subtypes. (G) Gene set variation analysis scores for proteomics based on differentially regulated gene ontology (GO) pathways in WHO subtypes (left heat map). Spearman correlation coefficients of the proteome and the transcriptome for the annotated pathways are displayed (right heat map, asterisks mark significantly correlated pathways with P < .05, Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected). (H) Heat map depicting kinome profiling with z scores calculated by kinase-substrate enrichment analysis algorithm. GSVA, gene set variation analysis; NOS, not otherwise specified; RNA-seq, RNA sequencing; TES, targeted exome sequencing; WES, whole exome sequencing.

Clinical characteristics of 374 patients newly diagnosed with AML

| Factor . | Whole cohort (N = 374) . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 49 (35-60) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 207 (55.3) |

| Female | 167 (44.7) |

| WBC, median (IQR), ×109/L | 20.1 (5.5-54.8) |

| HGB, median (IQR), g/L | 85 (68-104) |

| PLT, median (IQR), ×109/L | 34 (20-72) |

| BM blasts, median (IQR), % | 74 (58.5-87.5) |

| WHO category, n (%) | |

| AML with defining genetic abnormalities | |

| APL with PML::RARA fusion | 70 (18.7) |

| AML with RUNX1::RUNX1T1 fusion | 25 (6.7) |

| AML with CBFB::MYH11 fusion | 33 (8.8) |

| AML with DEK::NUP214 fusion | 2 (0.5) |

| AML with KMT2A rearrangement | 16 (4.3) |

| AML with NUP98 rearrangement | 10 (2.7) |

| AML with NPM1 mutation | 61 (16.3) |

| AML with CEBPA mutation | 60 (16) |

| AML, myelodysplasia-related | 58 (15.5) |

| AML, defined by differentiation | 39 (10.4) |

| ELN risk (non-M3), n (%) | |

| Favorable | 116 (38.2) |

| Intermediate | 69 (22.7) |

| Adverse | 119 (39.1) |

| Factor . | Whole cohort (N = 374) . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 49 (35-60) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 207 (55.3) |

| Female | 167 (44.7) |

| WBC, median (IQR), ×109/L | 20.1 (5.5-54.8) |

| HGB, median (IQR), g/L | 85 (68-104) |

| PLT, median (IQR), ×109/L | 34 (20-72) |

| BM blasts, median (IQR), % | 74 (58.5-87.5) |

| WHO category, n (%) | |

| AML with defining genetic abnormalities | |

| APL with PML::RARA fusion | 70 (18.7) |

| AML with RUNX1::RUNX1T1 fusion | 25 (6.7) |

| AML with CBFB::MYH11 fusion | 33 (8.8) |

| AML with DEK::NUP214 fusion | 2 (0.5) |

| AML with KMT2A rearrangement | 16 (4.3) |

| AML with NUP98 rearrangement | 10 (2.7) |

| AML with NPM1 mutation | 61 (16.3) |

| AML with CEBPA mutation | 60 (16) |

| AML, myelodysplasia-related | 58 (15.5) |

| AML, defined by differentiation | 39 (10.4) |

| ELN risk (non-M3), n (%) | |

| Favorable | 116 (38.2) |

| Intermediate | 69 (22.7) |

| Adverse | 119 (39.1) |

HGB, hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range; WBC, white blood cell count.

The correlation of protein-messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and the proteins associated with common molecular subtypes are provided (supplemental Figures 5 and 6; supplemental Data set 2). For most genetic subtypes, correlations between the differentially expressed proteins and their mRNAs were higher than those between other protein-mRNA pairs (supplemental Figure 5E). Intriguingly, p53 proteins were significantly upregulated, while TP53 transcripts were downregulated in AML samples with TP53 mutations (supplemental Figure 6). Moreover, functional enrichment analyses were performed for WHO-defined subtypes. Through gene set variation analysis of proteomics data, we identified several known biological phenotypes of AML subtypes, such as azurophil granule associated with PML::RARA, embryo and muscle development associated with HOX family genes in NPM1-mutated cases, and stem cell properties in AML-MR (Figure 1G). Kinase-substrate enrichment analysis of the phosphoproteome also revealed alterations in kinase activity within distinct subtypes, including the increased phosphorylation of PRKCD observed in AML with NPM1 mutations, as reported by Pino et al14 (Figure 1H). These findings substantiate the reliability of our multiomics data.

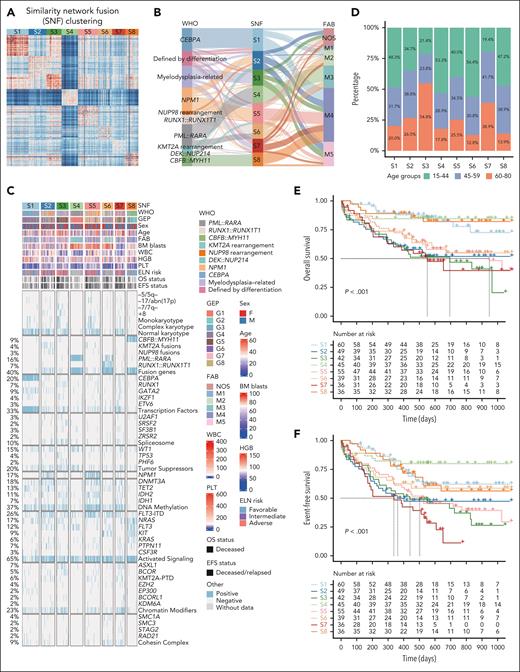

Establishment and validation of 8 proteomic subtypes in AML

To comprehensively dissect the global proteomic profiling of AML, we employed the SNF method. A range of 500 to 5000 proteins with the highest standard deviations were tested for clustering, and the top 2000 proteins were eventually selected to obtain 8 proteomic subtypes (S1-S8; Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 7A; supplemental Data set 3). Through using different numbers of proteins and various clustering methods, we further validated the robustness of the clustering results. Eight proteomic subtypes were identified using nonnegative matrix factorization and partitioning around medoids methods, which corresponded well to the subtypes established by the SNF method (supplemental Figure 7B-C). Proteomic classification could distinguish recurrent gene fusions and mutations in AML (supplemental Table 1; supplemental Data set 4), particularly evident for PML::RARA (S4 and S6), RUNX1::RUNX1T1 (S6), CBFB::MYH11 (S8), CEBPA mutations (S1), and NPM1 mutations (mainly S5), which were also in partial agreement with French-American-British subtypes and our previously established transcriptomic subgroups (Figure 2B-C; supplemental Figure 7D). The S3 subtype was enriched for AML-MR, which encompasses 8 secondary-type mutations per the fifth WHO classification,23 while S2 and S7 were 2 subtypes harboring heterogeneous gene mutations (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, patients with PML::RARA were distributed in S4 and S6 subtypes. Compared with cases in S4, those in S6 were more frequently categorized as high risk based on the Sanz criteria, and exhibited more FLT3-ITD mutations and a higher early death rate (supplemental Figure 7E-G). Clinical and molecular characteristics of AML-MR in S3 and other subtypes, and NPM1 mutations in S5 and other subtypes were also compared (supplemental Tables 2 and 3; supplemental Figure 7H-K). Collectively, the established proteomic subtypes demonstrated both consistent and unique features compared with the current AML classification system.

Proteomic subtypes of AML identified by similarity network clustering. (A) The discrimination of 8 proteomic subtypes (S1-S8) based on the SNF method. (B) Sankey plot indicating the relationship between the established proteomic subtypes and entities defined by the WHO and FAB classification. (C) Heat map of clinical features, cytogenetic groups, and recurrent gene fusions and mutations in AML, which are classified into diverse functional groups.3 Each column represents a patient, which is arranged according to the proteomic clusters (S1-S8). “FLT3” refers to FLT3 mutations other than FLT3-ITD, including FLT3-TKD and other site mutations. (D) The proportional distribution of age groups in S1 to S8 subtypes. (E-F) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (E) and EFS (F) of patients with AML stratified by the 8 proteomic subtypes. GEP, gene expression profiling; HGB, hemoglobin; NOS, not otherwise specified; WBC, white blood cell count.

Proteomic subtypes of AML identified by similarity network clustering. (A) The discrimination of 8 proteomic subtypes (S1-S8) based on the SNF method. (B) Sankey plot indicating the relationship between the established proteomic subtypes and entities defined by the WHO and FAB classification. (C) Heat map of clinical features, cytogenetic groups, and recurrent gene fusions and mutations in AML, which are classified into diverse functional groups.3 Each column represents a patient, which is arranged according to the proteomic clusters (S1-S8). “FLT3” refers to FLT3 mutations other than FLT3-ITD, including FLT3-TKD and other site mutations. (D) The proportional distribution of age groups in S1 to S8 subtypes. (E-F) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (E) and EFS (F) of patients with AML stratified by the 8 proteomic subtypes. GEP, gene expression profiling; HGB, hemoglobin; NOS, not otherwise specified; WBC, white blood cell count.

We proceeded to dissect the enriched pathways and regulatory networks of AML proteomic subtypes via gene set variation analysis (supplemental Data set 5; supplemental Figure 8). The S3 (AML-MR), S2 and S7 (mixed), and S8 (CBFB::MYH11) subtypes exhibited significant upregulation of immune and inflammatory response pathways, evident at both protein and mRNA levels. In contrast, the apparent upregulation of the mitochondrial gene expression pathway in S5 (NPM1 mutations) was only observed at the proteome level, which might coincide with the Mito-AML subtype previously reported by Jayavelu et al.8 Phosphoproteomic features of the 8 proteomic subtypes are also depicted (supplemental Figure 9; supplemental Data set 6).

Moreover, similar proteomic subtypes were validated using proteomics data reported by Pino et al14 (using newly diagnosed AML samples) and Kramer et al.9 These subtypes exhibited molecular characteristics and prognostic trends that aligned well with our findings (supplemental Figure 10). However, SNF-based phosphoproteomic subtypes did not demonstrate an association with existing molecular classifications (supplemental Figure 11), which was consistent with the UMAP analysis (Figure 1F). This finding suggests that the phosphoproteome of AML constitutes a distinct layer of biological information.

In terms of prognosis, patients in S1 (CEBPA mutations), S4 (PML::RARA), and S8 (CBFB::MYH11) subtypes conferred a longer OS, while those in S3 (AML-MR), S5 (NPM1), S2 and S7 (mixed) subtypes exhibited dismal OS and EFS, partly attributable to the older age of patients in these subtypes (Figure 2D-F; supplemental Table 1). Moreover, when stratified by age, the prognosis of S3, S5, and S7 subtypes remained poor among younger patients with AML, while S2 (mixed) and S6 (PML::RARA and RUNX1::RUNX1T1) subtypes demonstrated shorter OS and EFS for patients aged ≥60 years (supplemental Figure 12). Therefore, it is evident that the S2, S3, and S7 subtypes cannot be characterized by a single driver genetic lesion, and represent high-risk AML subtypes, highlighting the need for further in-depth exploration at the proteome level.

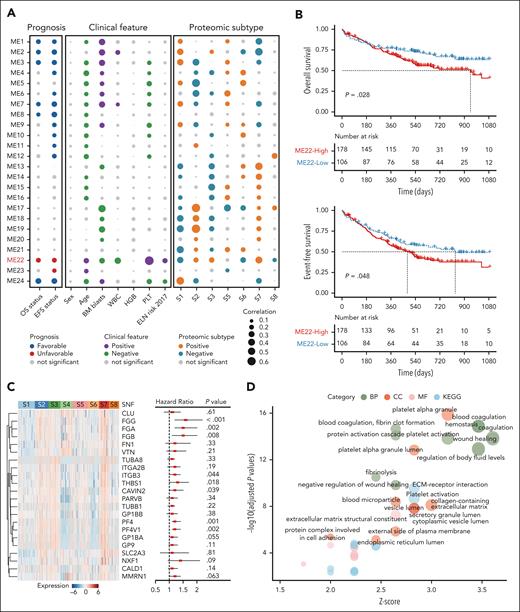

Abundance of proteins and phosphosites associated with aging in AML

We conducted weighted correlation network analysis to comprehensively unveil clinical- and subtype-related protein modules in AML. The functional protein module (ME22) was associated with S2, S3, and S7 subtypes. Besides, this module was linked to older age, higher PLT count, unfavorable European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk at diagnosis, and poor OS and EFS of patients (Figure 3A-B). Notably, proteins associated with ME22 encompassed a variety of megakaryocyte (MK)- and PLT-related markers. Among them, several proteins could significantly predict an adverse OS, such as PF4, PF4V1, FGG, FGA, FGB, ITGB3, and THBS1 (Figure 3C). Consistently, PLT- and coagulation-related pathways were enriched in S2, S3, and S7 subtypes as compared with other subtypes (Figure 3D). These results demonstrate that specific patterns of protein abundance are significantly associated with age and prognosis in AML, which may reflect the underlying molecular mechanisms of the disease.

Weighted correlation network analysis identifies functional protein modules with clinical relevance. (A) Bubble plot displaying 24 protein clusters (functional modules, ME1-24). Modules highly correlated with clinical features, molecular characteristics, and proteomic subtypes are colored. The ME22 is highlighted in red font. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (upper panel) and EFS (lower panel) of patients with AML stratified by protein abundance in ME22, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value. (C) Heat map showing the relative abundance of proteins derived from the ME22 module (left panel). Univariate Cox regression analysis indicating the prognostic value of each protein (right panel). The middle red points indicate the hazard ratio for each protein, and end points represent lower or upper 95% confidence intervals (CIs). (D) Pathway enrichment analysis of ME22-derived proteins between the combination of S2, S3, and S7 and patients with residual AML using BP, CC, and MF in GO, and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG). BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function.

Weighted correlation network analysis identifies functional protein modules with clinical relevance. (A) Bubble plot displaying 24 protein clusters (functional modules, ME1-24). Modules highly correlated with clinical features, molecular characteristics, and proteomic subtypes are colored. The ME22 is highlighted in red font. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (upper panel) and EFS (lower panel) of patients with AML stratified by protein abundance in ME22, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value. (C) Heat map showing the relative abundance of proteins derived from the ME22 module (left panel). Univariate Cox regression analysis indicating the prognostic value of each protein (right panel). The middle red points indicate the hazard ratio for each protein, and end points represent lower or upper 95% confidence intervals (CIs). (D) Pathway enrichment analysis of ME22-derived proteins between the combination of S2, S3, and S7 and patients with residual AML using BP, CC, and MF in GO, and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG). BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function.

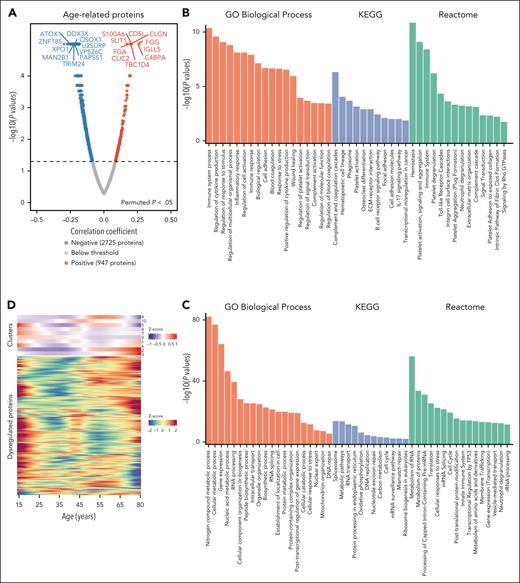

Next, we sought to comprehensively delineate the age-related posttranscriptional regulatory patterns in AML. We first investigated proteins that exhibited significant linear correlations with age. A total of 947 and 2725 proteins, respectively, were positively and negatively associated with age (permuted P < .05) using Spearman correlation analysis (Figure 4A; supplemental Data set 7). Pathways enriched in patients with advanced age were primarily involved in immune and inflammatory response, platelet activation, cell adhesion, and complement and coagulation cascades, etc. (Figure 4B). In contrast, pathways negatively correlated with age were fundamental cellular functions, such as various cellular metabolic pathways, RNA processing, translation, and DNA repair (Figure 4C). To provide a more intuitive outline of protein expression profiles in patients with AML as they changed with age, we applied Mfuzz to identify protein clusters that shared similar age-related expression trends across AML samples. Results showed that 10 age-related protein clusters were captured (Figure 4D, upper panel). Heat map using all 10 016 proteins was also depicted (Figure 4D, lower panel). We focused on the protein cluster 2, which exhibited a monotonically increasing trend alongside aging (Figure 4E). Proteins in this cluster were mainly involved in platelet-related functions (activation/aggregation), blood coagulation, myeloid and megakaryocyte differentiation, and immune response (Figure 4F).

Changes in protein abundance associated with aging. (A) Volcano plot of significantly changed proteins (permuted P < .05) during aging in AML, which were calculated using the Spearman correlation approach. (B-C) Pathway enrichment analysis of proteins showing positive (B) and negative (C) correlation with age through GO, biological process, KEGG, and reactome. (D) Heat maps displaying the trajectories of 10 protein clusters (upper panel) and all proteins (lower panel) that change with age in AML. (E) The 1104 proteins in cluster 2 display a monotonically increasing trend with age. (F) Enriched GO pathways of proteins in cluster 2. The size of the circles represents the count of proteins enriched in the GO term. The thickness of the edges denotes the semantic similarity between each pair of GO terms. The color of the circles indicates the adjusted significance of enrichment.

Changes in protein abundance associated with aging. (A) Volcano plot of significantly changed proteins (permuted P < .05) during aging in AML, which were calculated using the Spearman correlation approach. (B-C) Pathway enrichment analysis of proteins showing positive (B) and negative (C) correlation with age through GO, biological process, KEGG, and reactome. (D) Heat maps displaying the trajectories of 10 protein clusters (upper panel) and all proteins (lower panel) that change with age in AML. (E) The 1104 proteins in cluster 2 display a monotonically increasing trend with age. (F) Enriched GO pathways of proteins in cluster 2. The size of the circles represents the count of proteins enriched in the GO term. The thickness of the edges denotes the semantic similarity between each pair of GO terms. The color of the circles indicates the adjusted significance of enrichment.

Moreover, we interrogated age-related phosphosites in 217 patients with AML. There were 1054 and 535 phosphosites positively and negatively correlated with age, respectively (supplemental Figure 13A; permuted P < .05). We observed increased CDKs, MAPKs, and the PKC/PKA family (PRKCZ, PRKCD, and PRKACA) activity in patients with AML with advanced age (supplemental Figure 13B). The Mfuzz analysis demonstrated 10 age-related phosphosite clusters, with cluster 3 displaying a striking increase in patients aged >60 years (supplemental Figure 13C-D). Multiple substrates of CDKs and MAPKs exhibited increased phosphorylation in this cluster (supplemental Figure 14).

Establishment of HAS in AML

Given that the hematopoietic differentiation signature and immune-associated pathways were age-dependent and enriched in high-risk AML subtypes (S2, S3, and S7), and that we and others observed distinct cellular hierarchies along the HSC to myeloid differentiation axis in AML at the transcriptome level,5,6,28,29 we aimed to characterize the hematopoietic differentiation feature of the disease at the proteome level. We collected previously reported hematopoietic lineage- and immune-related proteins or genes,28,30,31 and the 22 proteins associated with ME22 (MK-/PLT-related), and subsequently calculated the protein abundance of these markers within S1 to S8 subtypes (supplemental Data sets 8 and 9). The S4 (PML::RARA) and S6 (PML::RARA and RUNX1::RUNX1T1) subtypes were characterized by granulocyte-monocyte progenitor-like signatures, while the S2 (mixed) and S8 (CBFB::MYH11) subtypes displayed more differentiated conventional dendritic cell- and monocyte-like features. It is of particular interest that the S3 (AML-MR) and S7 (mixed) subtypes demonstrated the coexpression of HSC/progenitor, immune cell, and MK-/PLT-related signatures, which might in part reflect the characteristics of hematopoietic senescence (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 15). Cellular properties derived from a more refined single-cell atlas exhibited similar hematopoietic hierarchies in these subtypes (supplemental Figure 16; supplemental Data set 8).32

Development and validation of the HAS. (A) Heat map depicting the protein abundance of various hematopoietic lineage markers across the 8 proteomic subtypes. (B) Proteins included in the HAS. The final score is calculated as the weighted sum of abundance of the 19 proteins. Proteins in red and blue are predictive for a poor and good prognosis, respectively. Coefficients of these proteins in univariate Cox regression analysis are denoted. (C) Heat map showing the established HAS and the abundance of the 19 proteins, with patients arranged according to the magnitude of their scores. Age and prognosis of patients are annotated above the heat map. (D) Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression analysis for OS in patients with AML. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs are listed next to variables. The dotted vertical line indicates an HR of 1. Red boxes denote the HR of each variable, and horizontal lines show 95% CIs. P values indicating the significance are shown on the right. (E) Heat map of markers incorporated into the HAS in an independent external data set. (F) The prognostic value of the HAS in univariate Cox regression in an independent external data set. (G) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (left panel) and EFS (right panel) stratified by the HAS in an external data set, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value.

Development and validation of the HAS. (A) Heat map depicting the protein abundance of various hematopoietic lineage markers across the 8 proteomic subtypes. (B) Proteins included in the HAS. The final score is calculated as the weighted sum of abundance of the 19 proteins. Proteins in red and blue are predictive for a poor and good prognosis, respectively. Coefficients of these proteins in univariate Cox regression analysis are denoted. (C) Heat map showing the established HAS and the abundance of the 19 proteins, with patients arranged according to the magnitude of their scores. Age and prognosis of patients are annotated above the heat map. (D) Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression analysis for OS in patients with AML. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs are listed next to variables. The dotted vertical line indicates an HR of 1. Red boxes denote the HR of each variable, and horizontal lines show 95% CIs. P values indicating the significance are shown on the right. (E) Heat map of markers incorporated into the HAS in an independent external data set. (F) The prognostic value of the HAS in univariate Cox regression in an independent external data set. (G) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (left panel) and EFS (right panel) stratified by the HAS in an external data set, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value.

To further capture the specific aging patterns of hematopoietic markers, we intersected the abovementioned hematopoietic lineage markers with the age-related proteins and the prognostic ones from univariate Cox regression analysis, leading to the identification of 19 proteins. A HAS was therefore established, which was calculated as the weighted sum of abundance of the 19 proteins (Figure 5B; supplemental Data set 9). The HAS was significantly higher in the S2, S3, and S7 subtypes (supplemental Figure 17A), and demonstrated a significant positive correlation with both stemness (LSC17 score) and MK (ME22 abundance) signatures (supplemental Figure 17B-C). Via fluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy, we validated the higher expression of the MK marker ITGA2B (CD41) in BM samples with high HAS, which was coexpressed with a subset of CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 17D). Older individuals, relapsed cases, and mortality events were significantly enriched with the increase of HAS (Figure 5C). After adjusting for age, sex, blood count, BM blasts, HSC transplantation, and ELN risk stratification, the HAS became an independent adverse prognostic factor in multivariate Cox regression analysis (Figure 5D). Moreover, the prognostic significance of HAS was validated in an external data set reported by Kramer et al,9 although the multivariate Cox regression analysis could not be performed in that data set due to limited sample size (N = 44; Figure 5E-G).

Clinical and biological significance of HAS

We aimed to delve deeper into the phenotypic traits and biological mechanisms associated with HAS in AML. Through using the HAS value with the most obvious prognostic discrimination as the cutoff, patients could be divided into high (n = 171) and low (n = 191) HAS groups (Figure 6A). This classification also showed significant prognostic stratification value in both ELN intermediate- and adverse-risk categories. For the ELN favorable-risk subgroup, patients with high HAS exhibited a significantly shorter EFS than those with low HAS (Figure 6B-D). Comparison of clinical and molecular abnormalities between the 2 groups is summarized (supplemental Table 4). Patients with high HAS exhibited apparently higher age (55 vs 43 years, P < .001) and PLT count (56 × 109/L vs 24 × 109/L, P < .001), while lower BM blasts (67.5% vs 81.5%, P < .001) and hemoglobin (82 g/L vs 89 g/L, P = .013) at diagnosis than those with low HAS, partly reflecting the myelodysplasia and megakaryocytic lineage-skewed hematopoiesis (Figure 6E). The high HAS group was significantly enriched for patients with AML-MR, NPM1 mutations, and those defined by differentiation (Figure 6F). Additionally, DNMT3A, ASXL1, TP53, RUNX1, spliceosome, and other epigenetic-related mutations were more frequently seen in patients with high HAS, which were reported to be associated with CH in the older population (supplemental Table 4).33

Clinical and biological significance of HAS. (A-D) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (upper panels) and EFS (lower panels) in all patients with AML (A), and patients with favorable (B), intermediate (C), and adverse (D) ELN risk stratified by the HAS, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value. (E) Comparison of age, WBC, HGB, PLT count, and BM blasts at diagnosis between high and low HAS groups. (F) Comparison of the proportion of WHO-defined entities between high and low HAS groups. (G) Heat map demonstrating the enrichment of known aging-associated pathways in AML, including aging hallmarks, epigenetic gene sets, and our previously reported enriched pathways with age relevance. The HAS group and clinical features of patients are annotated below the heat map. Each column represents a patient.

Clinical and biological significance of HAS. (A-D) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (upper panels) and EFS (lower panels) in all patients with AML (A), and patients with favorable (B), intermediate (C), and adverse (D) ELN risk stratified by the HAS, with the most obvious prognostic discrimination used as the cutoff value. (E) Comparison of age, WBC, HGB, PLT count, and BM blasts at diagnosis between high and low HAS groups. (F) Comparison of the proportion of WHO-defined entities between high and low HAS groups. (G) Heat map demonstrating the enrichment of known aging-associated pathways in AML, including aging hallmarks, epigenetic gene sets, and our previously reported enriched pathways with age relevance. The HAS group and clinical features of patients are annotated below the heat map. Each column represents a patient.

To explore the correlation between the HAS and known transcriptome-based pathways associated with aging, we calculated the single-sample gene set enrichment scores for the aging hallmarks, epigenetic gene sets, and enriched pathways associated with age that we previously reported.22 It could be observed that all cases were distinctly divided into 2 clusters, with cases showing high HAS predominantly aggregating in the first cluster. This cluster exhibited higher enrichment scores in inflammation response, stem cell differentiation, neuron-, calcium ion-, and platelet-related networks, cellular senescence, loss of proteostasis, altered intercellular communication, mitochondrial dysfunction, epigenetic factors, telomere attrition, genomic instability, etc, while ribosomal RNA processing, ribosome, protein biosynthesis, translation, and epigenetic remodel and reader were less enriched (Figure 6G). The high HAS group was also significantly associated with pathways enriched for age-related proteins, such as MK-/PLT-, and immune and inflammatory response-related pathways (supplemental Figure 18).

Although patients with high HAS responded poorly to the standard-of-care induction treatment (supplemental Figure 19A-C), via in vitro drug screening tests, several compounds exhibited considerable therapeutic efficacy in this group, as exemplified by histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat, CDK inhibitor alvocidib, and homoharringtonine. Of note, the combination of homoharringtonine, venetoclax, and azacitidine demonstrated a promising synergistic effect (supplemental Figure 19D-E; supplemental Data sets 10 and 11). These regimens hold therapeutic potential, and merit further investigation in preclinical and clinical studies.

Discussion

In this study, we generated and shared a multiomics data set in a large AML cohort. Notably, the proteomic nosology of AML corresponded closely to the latest WHO classification, validating the rationality of this widely used classification system from a new perspective. We also identified age-related hematopoietic abnormalities with particular protein markers, such as MK-/PLT-related protein expression in a sizable proportion of patients with AML. In addition, we established a HAS with independent prognostic value and biological relevance based on proteomic profiles, which showed significant correlations with aging hallmarks of AML at the genome and transcriptome levels.

Despite the lack of a high overall correlation coefficient between proteins and mRNAs, as previously reported,9,14 an obvious correlation was detected in functionally important genetic subtypes. In TP53-mutated AML, the p53 protein was upregulated while its mRNA was downregulated, which was also identified in other hematological neoplasms.34,35 The accumulation of mutant p53 may rely on posttranscriptional mechanisms (eg, acetylation-modifying complexes, HSP90/HDAC6 chaperone axis), contributing to its gain-of-function properties.34,36 These results highlight the unique advantage of proteomics in unraveling clinically relevant biomarkers within specific molecular subtypes.

Notably, the SNF clustering of proteins not only recapitulated the well-established genomic characteristics of AML but also reflected the unique subtyping value at the gene translational expression level, in that proteomic plasticity may contribute to malignant cell phenotypes, such as treatment resistance and clonal evolution beyond genetic factors.37 The proteomic data generated in this study were able to reproduce the key findings of previously published works, for example, Mito-AML and dysregulated mitochondrial proteins.8,9,14 The larger sample size, a wide spectrum of AML subtypes (including APL cases), concordant sample collection (newly diagnosed bone marrow mononuclear cells), the employment of the advanced 4-dimensional data-independent acquisition technology, and rigorous validation analyses could support the reliability of our findings and comprehensively reflect the global landscape of the AML proteome.

It is foreseeable that AML will experience a dramatic increase with global aging, which will impose a huge burden on health care systems. Older patients diagnosed with AML often exhibit age-related molecular features, which negatively impact their treatment response and long-term survival. In this study, we observed a significant age relevance of protein abundance patterns correlated with MK/PLT and inflammatory response in AML. Of interest, the MK/PLT lineage signatures, for example, FGA, FGB, FGG, and PF4, were predominantly present in S2, S3, and S7 subtypes, with the concurrent high expression of MK, HSC/progenitor, and immune cell markers observed in the latter 2 subtypes. Growing evidence shows that long-term HSCs can directly differentiate into megakaryocytes, skipping intermediate progenitors.38,39 MK can not only act as PLT-producing cells, but also behave as HSC niche cells and regulators of immune and inflammatory responses.40,41 Besides, MK may represent an important connection between the extrinsic and intrinsic mechanisms for HSC aging.38,42-44 As a result, MK and PLT might play a pivotal role in regulating immune responses and the BM microenvironment during aging, thereby affecting the HSC pool through the release of cytokines. Conversely, the inflammatory signaling may spur HSC bias toward the MK lineage. Hence, the interplay of MK, aging HSC, and the immune microenvironment collectively shapes the hematopoietic aging milieu in older individuals with AML, and contributes to disease progression.

In light of these findings, we proposed a HAS at the proteome level, which presented prognostic value in both our cohort and an independent validation data set. High HAS was more frequently seen in older patients with AML-MR, NPM1 mutations, and CH-associated genetic lesions, which are significant hallmarks of aging.45 We previously reported that PF4 was transcriptionally upregulated in older patients with AML.22 PF4 constituted an important factor of HAS, and its protein abundance was also upregulated in high-risk and older patients with AML. PF4 can exert antiaging effects in the normal older population, but may also suppress antitumor immunity and promote tumor growth.46-49 Of note, the HAS exhibited a strong correlation with multiple known aging-associated pathways, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying aging in AML. Panobinostat, alvocidib, and homoharringtonine may exert therapeutic efficacy in patients with high HAS. Homoharringtonine is a natural plant alkaloid that is widely used in China and exhibits encouraging antileukemia activity.50,51 Homoharringtonine combined with venetoclax plus azacitidine demonstrated a good synergistic effect, which was confirmed in a recent phase 2 clinical trial.52 Nevertheless, given the relative quantification nature of nontargeted proteomics methods, applying the HAS to new samples in the clinical setting may pose certain challenges. In future work, targeted MS techniques are required to establish a prognostic model based on absolute protein quantification.

In conclusion, this global posttranscriptional view of AML provides insights into the molecular landscape and inherent heterogeneity, dissects aging-related protein alterations, and expands the scope of precision medicine practices in the disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Adult Leukemia Registry of China for providing valuable clinical data for their research.

This work was supported by the State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, the Double First-Class Project (grant WF510162602) from the Ministry of Education, the Shanghai Collaborative Innovation Program on Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research (grant 2019CXJQ01), the Overseas Expertise Introduction Project for Discipline Innovation (111 Project; grant B17029), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 82230006, 82270166, 32470681, and 82300168), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (grant 2021-I2M-5-010), the Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (grants SHDC2020CR5002 and SHDC2024CRI073), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grants 2023M742323 and 2024M752038), the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (grant BX20230229), the Shanghai Sailing Program (grant 23YF1424400), the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases–National Science and Technology Major Project (grant 2023ZD0500700), the Innovative Research Team of High-Level Local Universities in Shanghai, and the Shanghai Guangci Translational Medical Research Development Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.-J.C., Y.S., and T.Y. designed and supervised the study; W.-Y.C., X.Y., Z.-Y.W., J.-F.L., and J.-Y.Z. performed research and analyzed data; X.-Q.W., T.H., Y.-M.Z., C.W., and S.-Y.W. processed samples and performed next-generation sequencing; W.-Y.C., X.Y., R.-H.Z., and T.Y. performed mass spectrometry assays; X.Y., Q.-Q.Z., X.L., S.W., and B.J. performed drug screening and experiments; W.-Y.C., W.Y., J.-N.Z., H.-Y.W., J.-M.L., H.-M.Z., L.C., and W.-F.W. collected clinical data; Y.-T.D., C.-X.G., and H.F. contributed analytic tools; W.-Y.C., X.Y., Z.-Y.W., and R.-H.Z. wrote the manuscript; and Z.C., S.-J.C., Y.S., H.F., J.-F.L., and T.Y. revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yang Shen, Shanghai Institute of Hematology, State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, National Research Center for Translational Medicine at Shanghai, Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Rui Jin Er Rd, Shanghai 200025, China; email: yang_shen@sjtu.edu.cn; Tong Yin, Shanghai Institute of Hematology, State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, National Research Center for Translational Medicine at Shanghai, Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Rui Jin Er Rd, Shanghai 200025, China; email: yintong0101@163.com; and Sai-Juan Chen, Shanghai Institute of Hematology, State Key Laboratory of Medical Genomics, National Research Center for Translational Medicine at Shanghai, Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 197 Rui Jin Er Rd, Shanghai 200025, China; email: sjchen@stn.sh.cn.

References

Author notes

W.-Y.C., X.Y., Z.-Y.W., J.-F.L., and J.-Y.Z. contributed equally to this study.

Raw proteomic and phosphoproteomic data are accessible via the Integrated Proteome Resources (iProX; IPX0008558000 via https://www.iprox.cn).

Raw RNA sequencing and targeted exome sequencing/whole exome sequencing data have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive for Human database (HRA007413 via https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/) under controlled access upon reasonable request.

Protein abundance, phosphosite profiles, and gene expression matrices have been deposited in the iProX (IPX0008558000 via https://www.iprox.cn) and Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14160480) databases.

Additionally, resources generated from this study are available for interactive exploration on the project website at http://www.genetictargets.com/PSAML. Source codes for reproducing all results, including figures and tables presented in this article can be accessed on the project website under the BOOK tab (http://www.genetictargets.com/PSAML/book).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal