Key Points

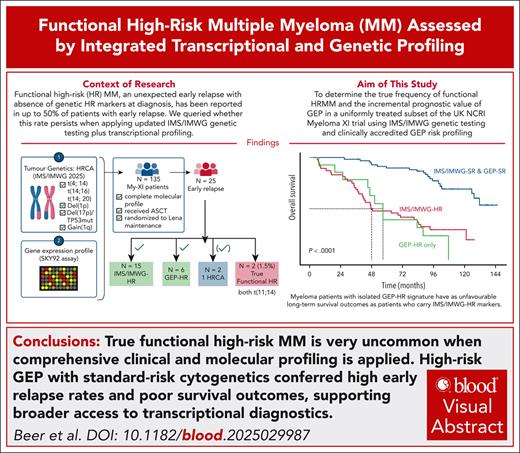

True functional high-risk MM is very uncommon when comprehensive clinical and molecular profiling is applied.

High-risk GEP with standard-risk genetics conferred high early relapse rates, advocating for broader access to transcriptional diagnostics.

Visual Abstract

Functional high-risk (FHR) multiple myeloma (MM) is defined as an unexpected, early relapse (ER) of disease in the absence of baseline molecular or clinical risk factors (RF), making FHR MM inherently dependent on which RFs were assessed at diagnosis, and what treatment patients received. To establish the true incidence of FHR, we analyzed uniformly treated, transplant-eligible patients from the Myeloma-XI (MyXI) trial that had been profiled for the International Myeloma Society and Working Group (IMS/IMWG) defined high-risk cytogenetic aberrations (HRCA), and the SKY92 gene expression HR signature (GEP-HR). A total of 135 MyXI patients were studied, with a median follow-up of 88 months; 25 (18.5%) experienced ER, defined as relapse <18 months from maintenance randomization post–autologous stem-cell transplantation. Hereof, 15 (60%) were IMS/IMWG-HR at diagnosis, of whom 8 were also GEP-HR. Another 6 patients were GEP-HR only and would have been missed by IMS/IMWG-HR. Among 4 patients with IMS/IMWG– and GEP–standard risk, 2 had isolated HR markers at diagnosis, leaving only 2 patients (8% of ER; 1.5% of all) truly meeting all FHR-criteria. Combined IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR profiling identified 84% of ER, and differentiated long-term outcome across all 135 patients: co-occurring IMS/IMWG and GEP-HR was associated with very short overall survival compared to the absence of both (HR = 13.1; 95% CI, 6.5-26.1, P < .0001), followed by GEP-HR only (HR = 5.1; 95% CI, 2.4-11.1, P < .0001) and IMS/IMWG-HR only (HR = 3.2; 95% CI, 1.6-6.2, P = .0007). Our results support more comprehensive baseline diagnostic profiling to identify those at risk of ER upfront. The trials were registered at the ISRCTN Registry as ISRCTN49407852 and at clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01554852.

Introduction

Frontline therapies for multiple myeloma (MM) have advanced significantly over the past 2 decades, especially in transplant-eligible (TE) newly diagnosed patients (NDMM).1 Combination induction regimens, including immunomodulatory drugs (eg, thalidomide-based cereblon degraders), proteasome inhibitors, and anti-CD38 antibodies, followed by high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), have made treatment responses the norm rather than the exception.2,3

Lenalidomide (Len) maintenance post-ASCT has been shown to improve both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), leading to its global approval.4 With the loss of patent exclusivity, Len use has expanded worldwide, including in lower-income countries.2 However, not all patients benefit equally; some early relapse (ER) and are classified as having high-risk multiple myeloma (HRMM). While many HRMM cases show molecular risk factor (mRF) or clinical risk factors (cRF) at diagnosis, others, termed functional high-risk (FHR) MM, relapse unexpectedly within 24 months despite lacking such markers.5,6 FHR may account for one-third to half of all ER cases,7-10 raising concerns about the reliability of current risk stratification and highlighting challenges in implementing early, risk-adapted therapies, as seen in OPTIMUM/MUKnine and German-speaking myeloma multicenter group GMMG-CONCEPT trials.11-13

Estimates of FHR prevalence have often come from cohorts with nonuniform treatment or incomplete molecular data. Until 2025, the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) definition of HRMM considered only t(4;14), t(14;16), and del(17p) as mRF, which are commonly used in registrational trials. The same was true before the second revision (R2-ISS) of the revised international staging system (R-ISS); the former still excluding t(14;16) as mRF. The updated International Myeloma Society (IMS)/IMWG definition now incorporates del(17p), TP53 mutations and biallelic del(1p32) as HR features; it furthermore classifies as HR those cases in which t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), monoallelic del(1p32) and/or gain(1q21) co-occur.14 But neither IMS/IMWG nor R2-ISS consider the validated and independent prognostic role of transcriptional or gene expression profiling (GEP),15,16 despite growing evidence supporting its additional clinical utility.17,18 To better estimate FHR MM prevalence under current diagnostic standards, we analyzed a uniformly treated, comprehensively profiled subgroup from the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute (UK NCRI) Myeloma XI (MyXI) trial, using certified diagnostic tests.

Materials and methods

Patients

A subgroup of 135 TE NDMM patients from the UK NCRI MyXI phase 3 trial was selected for analysis. All patients met the following inclusion criteria: (i) complete data for all high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities (HRCAs) defined by IMS/IMWG-HR,14 including t(4;14), t(14;16), t(14;20), gain(1q21), del(1p32), and del(17p); (ii) an available SKY-92 gene expression profile (GEP); and (iii) randomization to Len maintenance post-ASCT. We refer to gain(1q21) as gain(1q) and del(1p32) as del(1p) throughout the manuscript. The design and main outcomes of MyXI have been previously reported.4 ER was defined as disease progression within 18 months of post-ASCT maintenance randomization, corresponding to relapse within 24 months of diagnosis. Depth of response and progression were assessed according to the IMWG criteria. PFS was measured from the time of maintenance randomization to progression or death from any cause, and OS was calculated from the same time point to death from any cause.

The Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained for all patients included within the MyXI (Medical Research Ethics Committee 17/09/09, International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number 49407852).

Samples and molecular profiling

MM cells were isolated from bone marrow (BM) aspirate samples at diagnosis and enriched to >95% purity using immune-magnetic cell sorting with anti-CD138 antibodies (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) were extracted with either RNA/DNA mini kit or AllPrep kits (Qiagen), following the manufacturers’ protocols. Cytogenetic abnormalities were centrally assessed in BM samples using multiplexed ligation-dependent probe amplification (P425-B1 MM probemix; MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for copy number aberrations and a TC (translocation/cyclin D expression) classification–based multiplex quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, as previously described and validated against fluorescence in situ hybridization.4,19-22 Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) of TP53 coding regions was performed for 11 ER cases lacking translocations or copy number aberrations using the UKAS15189-accredited RMH200 HaemOnc panel (Clinical Genomics Laboratory, The Royal Marsden Hospital), in accordance with National Health Services England guidelines.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (v2024.12.0). Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests, and continuous variables with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Survival outcomes were assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and log-rank tests, implemented via “survival,” “survminer” and “ggplot2” packages. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were two-sided and P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Sankey plots were generated using the “ggplot2” and “ggalluvial” packages. Oncoplots were coded with the packages “ComplexHeatmap” and “circlize.”

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

Of 897 MyXI patients with available genetic information, 552 underwent ASCT and maintenance randomization. Of these, 135 met all inclusion criteria, including available GEP data, and were included in this study (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website). By design, all 135 patients received ASCT and were randomized to Len maintenance. Median follow-up from randomization was 88.3 months (interquartile range [IQR], 47.3-104).

Of these 135 patients, 25 (18.5%) experienced ER (Figure 1A). Of the 110 non-ER patients, 66 experienced a late relapse at a median of 52.3 months (IQR, 30.7-70.3), compared to a median of 9.8 months (IQR, 4.5-16.3) in the ER group. Baseline clinical and treatment characteristics of ER and non-ER groups are summarized in Table 1. As per inclusion criteria, extended genetic profiles were available for all 135 patients, with the frequency of individual lesions consistent with previously reported MyXI data (Table 1).4

Study overview and risk profiles of ER patients. (A) Functional HR MM in 135 MyXI trial patients was determined using advanced molecular profiling, including HRCA per updated IMS/IMWG-HR criteria and GEP-HR based on the SKY92 signature. (B) Bar chart illustrating the composition of 4 risk groups based on IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR classification (SR, IMS/IMWG-HR, GEP-HR, and IMS/IMWG-HR & GEP-HR) in the 25 patients with ER. CTPC, circulating tumor plasma cells; Lena, lenalidomide; PCL, plasma cell leukemia. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Study overview and risk profiles of ER patients. (A) Functional HR MM in 135 MyXI trial patients was determined using advanced molecular profiling, including HRCA per updated IMS/IMWG-HR criteria and GEP-HR based on the SKY92 signature. (B) Bar chart illustrating the composition of 4 risk groups based on IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR classification (SR, IMS/IMWG-HR, GEP-HR, and IMS/IMWG-HR & GEP-HR) in the 25 patients with ER. CTPC, circulating tumor plasma cells; Lena, lenalidomide; PCL, plasma cell leukemia. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Clinical, laboratory, and molecular characteristics of the study cohort

| . | ER group N = 25 . | Non-ER group N = 110 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and treatment characteristics | |||

| Age, mean (range), y | 57.9 (44-69) | 56.6 (28-69) | .5 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 18 (72) | 74 (67) | .83 |

| WHO PS, median (range) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | .77 |

| b2m, mean (range), mg/L | 5.7 (2-17.5) | 4.8 (1.6-20) | .419 |

| >5.5, n (%) | 7 (28) | 24 (22) | .58 |

| >5.5 & creatine <1.2 mg/dL, n (%) | 4 (16) | 13 (12) | |

| Unknown | 8 (32) | 31 (28) | NA |

| Hemoglobin level, mean (range), g/L | 99.4 (52-151) | 107.3 (63-151) | .06 |

| ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (4) | 21 (19) | .018∗ |

| 2 | 9 (36) | 24 (22) | .12 |

| 3 | 7 (28) | 18 (16) | .59 |

| R-ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 9 (8) | .024∗ |

| 2 | 14 (56) | 44 (40) | .08 |

| 3 | 3 (12) | 10 (9) | 1 |

| R2-ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 9 (8) | .21 |

| 2 | 1 (4) | 38 (34.5) | .03∗ |

| 3 | 12 (48) | 53 (48) | .38 |

| 4 | 4 (16) | 10 (9) | .02∗ |

| Unknown ISS/R-ISS/R2-ISS | 8 (32) | 47 (43) | NA |

| MM type, n (%) | |||

| IgG | 15 (60) | 62 (56) | .8 |

| IgA | 7 (28) | 31 (28) | 1 |

| LCO | 2 (8) | 13 (12) | .7 |

| IgM | 1 (4) | 0 | .2 |

| IgD | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | NA |

| HDC/ASCT, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | 1 |

| Response premaintenance, n (%) | |||

| CR | 6 (24) | 35 (32) | .63 |

| VGPR | 15 (60) | 64 (58) | 1 |

| PR | 4 (16) | 10 (9) | .29 |

| Len maintenance, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | 1 |

| Molecular characteristics | |||

| Complete genetic panel, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | NA |

| HRD | 10 (40) | 56 (51) | .45 |

| t(4;14) or t(14;16) or t(14;20) | 11 (44) | 22 (20) | < .01∗∗ |

| t(11;14) | 5 (20) | 18 (16) | .89 |

| 1q+ | 14 (56) | 43 (39) | .09 |

| Gain 1q | 11 (44) | 32 (29) | |

| Amp1q | 3 (12) | 11 (10) | |

| Del1p, n (%) | 6 (24) | 13 (12) | .2 |

| Hemizygous deletion of 1p | 4 (16) | 11 (10) | |

| Homozygous deletion of 1p | 2 (8) | 2 (2) | |

| Del17p, n (%) | 5 (20) | 11 (10) | .29 |

| Hemizygous deletion of 17p | 5 (20) | 11 (10) | |

| Homozygous deletion of 17p | 0 | 0 | |

| Number of HRCA, n (%) | |||

| 0 HRCA | 7 (28) | 50 (45.5) | .12 |

| 1 HRCA (single hit) | 6 (24) | 38 (34.5) | .35 |

| 2 or more HRCA (double hit) | 12 (48) | 22 (20) | < .01∗∗ |

| 3 or more HRCA (triple hit) | 5 (20) | 6 (5) | .03∗ |

| IMS/IMWG-HR, n (%)† | |||

| Standard risk | 11 (44) | 76 (69) | .03∗ |

| High risk | 14 (56) | 34 (31) | |

| GEP-HR (SKY-92 signature), n (%) | |||

| Standard risk | 11 (44) | 91 (82.7) | < .01∗∗ |

| High risk | 14 (56) | 19 (17.3) | |

| IMS/IMWG- & GEP-SR† | 5 (20) | 68 (62) | .01∗ |

| IMS/IMWG- & GEP-HR† | 8 (32) | 11 (10) |

| . | ER group N = 25 . | Non-ER group N = 110 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical and treatment characteristics | |||

| Age, mean (range), y | 57.9 (44-69) | 56.6 (28-69) | .5 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 18 (72) | 74 (67) | .83 |

| WHO PS, median (range) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | .77 |

| b2m, mean (range), mg/L | 5.7 (2-17.5) | 4.8 (1.6-20) | .419 |

| >5.5, n (%) | 7 (28) | 24 (22) | .58 |

| >5.5 & creatine <1.2 mg/dL, n (%) | 4 (16) | 13 (12) | |

| Unknown | 8 (32) | 31 (28) | NA |

| Hemoglobin level, mean (range), g/L | 99.4 (52-151) | 107.3 (63-151) | .06 |

| ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (4) | 21 (19) | .018∗ |

| 2 | 9 (36) | 24 (22) | .12 |

| 3 | 7 (28) | 18 (16) | .59 |

| R-ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 9 (8) | .024∗ |

| 2 | 14 (56) | 44 (40) | .08 |

| 3 | 3 (12) | 10 (9) | 1 |

| R2-ISS, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 9 (8) | .21 |

| 2 | 1 (4) | 38 (34.5) | .03∗ |

| 3 | 12 (48) | 53 (48) | .38 |

| 4 | 4 (16) | 10 (9) | .02∗ |

| Unknown ISS/R-ISS/R2-ISS | 8 (32) | 47 (43) | NA |

| MM type, n (%) | |||

| IgG | 15 (60) | 62 (56) | .8 |

| IgA | 7 (28) | 31 (28) | 1 |

| LCO | 2 (8) | 13 (12) | .7 |

| IgM | 1 (4) | 0 | .2 |

| IgD | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (2) | NA |

| HDC/ASCT, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | 1 |

| Response premaintenance, n (%) | |||

| CR | 6 (24) | 35 (32) | .63 |

| VGPR | 15 (60) | 64 (58) | 1 |

| PR | 4 (16) | 10 (9) | .29 |

| Len maintenance, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | 1 |

| Molecular characteristics | |||

| Complete genetic panel, n (%) | 25 (100) | 110 (100) | NA |

| HRD | 10 (40) | 56 (51) | .45 |

| t(4;14) or t(14;16) or t(14;20) | 11 (44) | 22 (20) | < .01∗∗ |

| t(11;14) | 5 (20) | 18 (16) | .89 |

| 1q+ | 14 (56) | 43 (39) | .09 |

| Gain 1q | 11 (44) | 32 (29) | |

| Amp1q | 3 (12) | 11 (10) | |

| Del1p, n (%) | 6 (24) | 13 (12) | .2 |

| Hemizygous deletion of 1p | 4 (16) | 11 (10) | |

| Homozygous deletion of 1p | 2 (8) | 2 (2) | |

| Del17p, n (%) | 5 (20) | 11 (10) | .29 |

| Hemizygous deletion of 17p | 5 (20) | 11 (10) | |

| Homozygous deletion of 17p | 0 | 0 | |

| Number of HRCA, n (%) | |||

| 0 HRCA | 7 (28) | 50 (45.5) | .12 |

| 1 HRCA (single hit) | 6 (24) | 38 (34.5) | .35 |

| 2 or more HRCA (double hit) | 12 (48) | 22 (20) | < .01∗∗ |

| 3 or more HRCA (triple hit) | 5 (20) | 6 (5) | .03∗ |

| IMS/IMWG-HR, n (%)† | |||

| Standard risk | 11 (44) | 76 (69) | .03∗ |

| High risk | 14 (56) | 34 (31) | |

| GEP-HR (SKY-92 signature), n (%) | |||

| Standard risk | 11 (44) | 91 (82.7) | < .01∗∗ |

| High risk | 14 (56) | 19 (17.3) | |

| IMS/IMWG- & GEP-SR† | 5 (20) | 68 (62) | .01∗ |

| IMS/IMWG- & GEP-HR† | 8 (32) | 11 (10) |

Boldface P values indicate significance: ∗, <.05; ∗∗, <.01.

CR, complete response; HDC/ASCT, high-dose chemotherapy/autologous stem cell transplantation; HRCA, high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities; ISS, International Staging System; LCO, Light chain only; NA, not applicable; PR, partial response; VGPR, very good partial response; WHO PS, World Health Organization performance status.

IMS/IMWG-HR in this table is defined exclusively by cytogenetic aberrations and does not consider TP53 mutation status, which was only assessed in 11 patients, with 1 patient found to harbor a TP53 mutation (see Figure 1).

Early relapse and baseline risk factors

To estimate the extent of FHR, defined as ER with absence of any baseline mRF or cRF, we analyzed the 25 patients who experienced ER. Using the IMS/IMWG-HR defined mRF, 12 patients (48%) were classified as HR, including 7 with ≥2 HRCAs and 5 with ≥3 HRCAs. Incorporating the cRF β2 microglobulin (b2m), 2 additional cases without genetic aberrations were classified as HR. We additionally performed targeted NGS of TP53 for the 11 ER patients classified IMS/IMWG–standard risk (SR). One ER patient without translocations or copy number aberrations carried an isolated clonal, pathogenetic TP53 mutation (codon 309 C>A; variant allele frequency [VAF] 0.58). This patient also showed elevated lactate dehydrogenase as a cRF at diagnosis, bringing the total to 15 IMS/IMWG-HR (60%) (Figure 1B). Of these 15 IMS/IMWG-HR patients, 8 also met GEP-HR criteria—all having gain(1q), 6 (75%) with del(1p), and 4 (50%) with ≥3 HRCAs. Of the remaining 10 IMS/IMWG-SR patients, 6 were GEP-HR at diagnosis, including 4 with a single HRCA (Figure 1B). Of the final 4 patients with neither IMS/IMWG-HR nor GEP-HR features, 2 had isolated HRCAs (one with t(4;14) and one with gain(1q)). While these cases did not meet IMS/IMWG-HR criteria, they do not qualify as FHR due to the presence of at least one mRF. Applying a strict FHR definition only 2 patients (8% of ER; 1.5% of the total cohort) met criteria. Notably, both harbored a t(11;14) translocation (Figure 1B).

Predictive value of baseline risk factors

Given the importance of early risk identification for timely intervention, we assessed the sensitivity and specificity of updated classifiers for ER in context of this MyXI subgroup in receipt of ASCT and Len maintenance. Analyses were based on IMS/IMWG-defined HRCA alone, since TP53 mutation status was not available for all 135 patients. On this basis, both IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR identified 14 of the 25 ER cases, yielding a sensitivity of 56% for each (supplemental Table 2). Although these groups partially overlapped, nearly half (48%) of ER cases were flagged by only 1 of the 2 methods, suggesting that IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR capture distinct aspects of HR biology.

Across all 135 patients, GEP-HR demonstrated greater specificity for ER (83%; 95% CI, 74.3-89.3) than IMS/IMWG-HR (68%; 95% CI, 58.6-76.7). When patients with elevated b2m but no mRF were excluded from the IMS/IMWG-HR group, specificity improved to 76.4%, although sensitivity dropped to 48%. Redefining ER as relapse within 24 months of ASCT (instead of 18 months after maintenance randomization) did not increase the sensitivity of either classifier (both remained at 58.3%) but improved the specificity of GEP-HR to 88% (supplemental Table 2). Combining GEP-HR and/or IMS/IMWG-HR into a single risk group increased sensitivity for ER to 80%, with a specificity of 62%. When applying the 24-month definition, sensitivity and specificity were 80.6% and 66.7%, respectively (for ER <24 months: 80.6% sensitivity, 66.7% specificity). To further explore the complementary value of these classifiers, we defined 4 risk categories: (i) Dual High-Risk: IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR; (ii) GEP-HR only: GEP-HR with IMS/IMWG-SR; (iii) IMS/IMWG-HR only: IMS/IMWG-HR with GEP-SR and (iv) Standard-Risk (SR): IMS/IMWG-SR & GEP-SR.

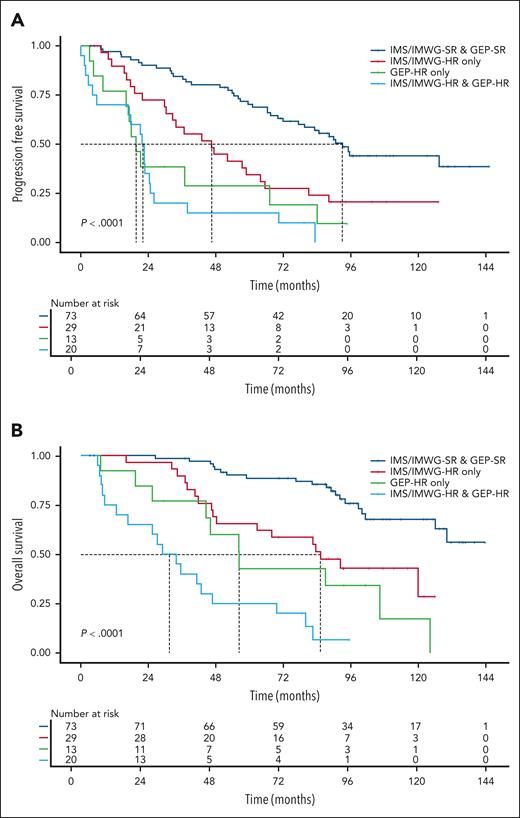

Survival outcome

Based on these findings and the extended follow-up in MyXI, we evaluated survival outcomes beyond the binary ER classification across the 4 defined risk groups. Relative to IMS/IMWG-SR & GEP-SR (median PFS: 93.0 months), PFS was poorest for patients with IMS/IMWG-HR & GEP-HR (median PFS, 22.1 months; hazard ratio [HR], 5.9; 95% CI, 3.3-10.6; P < .0001), followed by GEP-HR (median PFS, 19.6 months; HR, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.1-8.2; P < .0001) and IMS/IMWG-HR (median PFS, 46.5 months; HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4-3.9; P = .0013) (Figure 2A). Risk discrimination was consistent and even more pronounced for OS. Patients with dual HR had the shortest OS (median, 31.9 months; HR, 13.1; 95% CI, 6.5-26.1; P < .0001), followed by GEP-HR only (median, 53.2 months; HR, 6.4; 95% CI, 3.1-13.2; P < .0001) and IMS/IMWG-HR only (median, 82.8 months; HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.4-5.8; P = .004) (Figure 2B).

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for the entire study cohort (n = 135). (A) PFS and (B) OS stratified by IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR classification (SR, IMS/IMWG-HR, GEP-HR, IMS/IMWG-HR & GEP-HR). x-axis, time since maintenance randomization (months); y-axis, survival probability; risk tables, number of patients at risk. Log-rank P values are shown. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for the entire study cohort (n = 135). (A) PFS and (B) OS stratified by IMS/IMWG-HR and GEP-HR classification (SR, IMS/IMWG-HR, GEP-HR, IMS/IMWG-HR & GEP-HR). x-axis, time since maintenance randomization (months); y-axis, survival probability; risk tables, number of patients at risk. Log-rank P values are shown. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Interestingly, patients classified as IMS/IMWG-HR solely based on b2m elevation but with no mRF (n = 10) had a median OS of nearly 8 years (92.3 months; 95% CI, 34.6 to NA), which did not differ significantly from the SR group (P = .23; supplemental Figure 1A-B).

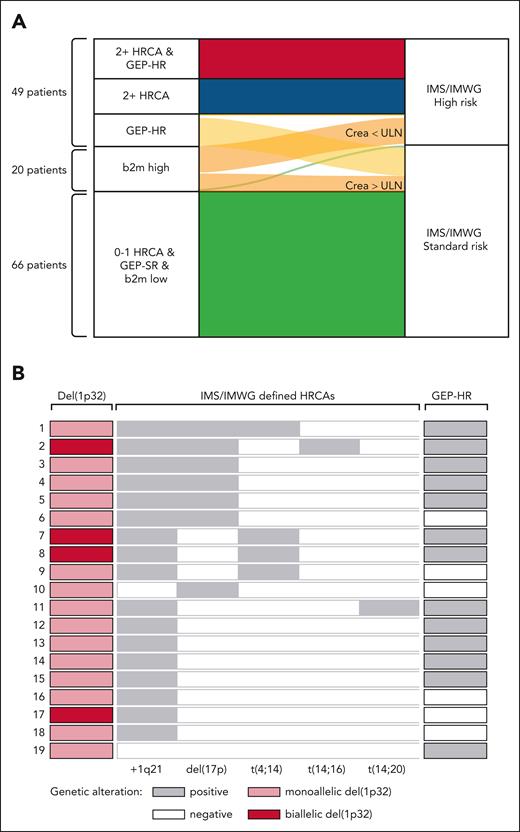

Composition and overlap of risk classifiers

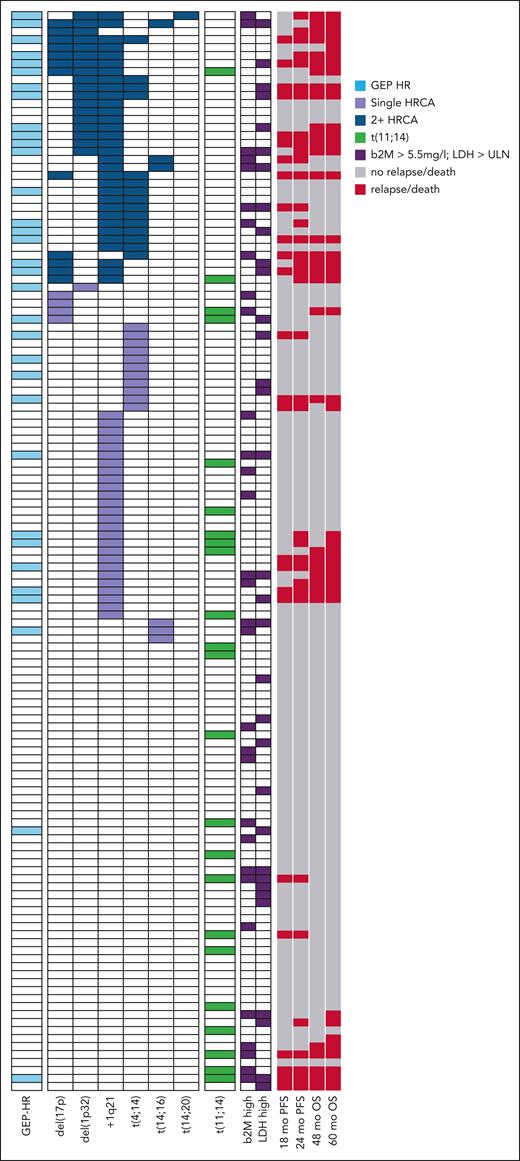

Comprehensive molecular profiling allowed assessment of the contribution of individual lesions to the updated IMS/IMWG-HR classification and their overlap with GEP-HR (Figure 3A). The concordance between HRCA count and the individual risk classifiers IMS/IMWG, GEP status, and R-ISS is illustrated in supplemental Figure 2A-C. Among IMS/IMWG-HR patients, 71% had ≥2 HRCAs. Elevated b2m without renal impairment accounted for 12% (n = 10) of IMS/IMWG-HR classifications. A total of 14 patients (10%) were classified as GEP-HR without meeting IMS/IMWG-HR criteria (Figure 3A). Of these, 12 had a single HRCA: gain(1q) (n = 6), t(4;14) (n = 4), t(14;20) (n = 1), and del(1p) (n = 1). Del(1p) was present in 19 patients (14%), with 68% also GEP-HR. Most del(1p) cases co-occurred with gain(1q) (90%), del(17p) (37%), or t(4;14) (21%). Four cases (21%) had biallelic deletions, all with ≥2 HRCAs (Figure 3B). Among IMS/IMWG-SR patients, over half had at least one risk feature: 44% had a single HRCA, 16% were GEP-HR, and 13% had elevated b2m with renal impairment (creatinine >106 mmol/L). The most common single abnormality in this group being gain (1q) (61%), followed by t(4;14) (29%) and t(14;16) (10%). Isolated gain(1q) was also found in 43% of GEP-HR cases lacking additional IMS/IMWG-HR features, although most gain(1q) tumors were not GEP-HR. Co-occurrence of HR features and their association with patient outcome is shown in Figure 4.

Composition of HR features according to updated IMS/IMWG-HR classification. (A) Sankey plot illustrating the composition and contribution of individual risk factors to the updated IMS/IMWG-HR classification. Six groups are displayed based on combinatorial risk features, including HRCA count, GEP signature, and isolated b2m elevation. Elevated b2m is subdivided by creatinine levels below or above the ULN, according to the IMS/IMWG-HR definition. One patient with GEP-HR carried an isolated del(17p) and was therefore also classified as IMS/IMWG-HR. TP53 mutation status was not included in this analysis because only 11 patients in the study had available information. (B) Co-occurrence of HR genetic features in patients harboring del(1p32). Each row represents 1 of 19 individual patients, while columns indicate the presence (gray) or absence (white) of an HR feature, including IMS/IMWG-defined HRCAs and GEP-HR. Biallelic del(1p32) are highlighted in dark red. ULN, upper limit of normal. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Composition of HR features according to updated IMS/IMWG-HR classification. (A) Sankey plot illustrating the composition and contribution of individual risk factors to the updated IMS/IMWG-HR classification. Six groups are displayed based on combinatorial risk features, including HRCA count, GEP signature, and isolated b2m elevation. Elevated b2m is subdivided by creatinine levels below or above the ULN, according to the IMS/IMWG-HR definition. One patient with GEP-HR carried an isolated del(17p) and was therefore also classified as IMS/IMWG-HR. TP53 mutation status was not included in this analysis because only 11 patients in the study had available information. (B) Co-occurrence of HR genetic features in patients harboring del(1p32). Each row represents 1 of 19 individual patients, while columns indicate the presence (gray) or absence (white) of an HR feature, including IMS/IMWG-defined HRCAs and GEP-HR. Biallelic del(1p32) are highlighted in dark red. ULN, upper limit of normal. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Oncoplot illustrating HR features at an individual patient level (n = 135), including IMS/IMWG-defined HRCAs, GEP-HR, t(11;14), and elevated b2m or LDH. ER as in PFS (defined as <18 months or <24 months) and OS events (at 48 and 60 months) are shown in red, while no event displayed in gray. Co-occurrence of ≥2 HR features appear in dark blue, single HR features in light purple, and no HR feature in white. Translocation t(11;14) is separately listed in green. Elevated laboratory parameters (b2m, LDH) are marked in dark purple. TP53 mutation status was not included in this analysis, as only 11 patients in the study had available information. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Oncoplot illustrating HR features at an individual patient level (n = 135), including IMS/IMWG-defined HRCAs, GEP-HR, t(11;14), and elevated b2m or LDH. ER as in PFS (defined as <18 months or <24 months) and OS events (at 48 and 60 months) are shown in red, while no event displayed in gray. Co-occurrence of ≥2 HR features appear in dark blue, single HR features in light purple, and no HR feature in white. Translocation t(11;14) is separately listed in green. Elevated laboratory parameters (b2m, LDH) are marked in dark purple. TP53 mutation status was not included in this analysis, as only 11 patients in the study had available information. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. Figure created with biorender.com. Houlston R. (2025) https://biorender.com/0vv82j9.

Discussion

In this study, we used a uniformly treated and comprehensively profiled cohort of transplant-eligible patients with NDMM to assess the prevalence and characteristics of FHR disease. True FHR MM, here defined as ER in the absence of both mRF and cRF, proved to be relatively rare in our analysis. Prior estimates of FHR prevalence appear inflated in settings where baseline diagnostic assessments were incomplete, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive risk profiling at diagnosis. Notably, in line with most authors,23 we consider as true FHR only those patients with complete absence of baseline mRF and cRF, as these patients pose the biggest diagnostic challenge, rather than using the term synonymously for ER.

Our results indicate that ER is significantly enriched among patients classified as high risk by GEP, which emerged as one of the most specific predictors of ER. Reliance on IMS/IMWG-defined risk alone, even though updated criteria are markedly more sensitive, may still miss around 10% of NDMM patients at risk of ER, who can be identified by GEP. We also demonstrate that incorporating GEP can isolate an ultra-HR subset of patient as a specific target group for new, innovative treatment approaches. Therefore, our data supports the argument for routine incorporation of GEP-HR assessment into frontline diagnostics, consistent with recent findings.17,18 Historically, limited access to tumor RNA has constrained the use of GEP, but RNA is increasingly obtainable as a by-product of DNA extraction for NGS workflows, in line with recent updates to IMS/IMWG risk assessment guidelines.

Importantly, combining IMS/IMWG-HR and SKY92-based GEP-HR identified 84% of patients with ER, and captured a broader population with consistently inferior PFS and OS. This combined approach offers a strong foundation for early identification of HR patients and timely deployment of intensified treatment strategies, such as those explored in the OPTIMUM/MUKnine and GMMG-CONCEPT protocols. Moreover, since most HRMM trials are single-arm studies, prospectively stratifying the HR cohort by GEP status could provide a valuable benchmark, enable external comparisons, and increase the validity of outcome assessments.

Nonetheless, our findings underscore a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity in ER prediction. This highlights the role of nonbiological factors, such as treatment adherence, tolerability, or real-world drug exposure, that are not captured in baseline diagnostics. For example, challenges with oral therapy like Len maintenance may contribute to relapse risk independently of MM biology.24 Moreover, conventional mRF and cRF may not fully capture disease heterogeneity or predict response to therapies designed to exploit plasma cell vulnerabilities as described by Boise et al.25 Interestingly, the two remaining FHR cases we identified harbored t(11;14), a translocation associated with a more B-cell–like transcriptional program,26 as well as plasma cell leukemia, which may impact responsiveness to plasma cell-targeting therapies. The biological implications of this phenotype remain to be established but suggest a need for more tailored therapeutic strategies. Several RF now recognized as clinically relevant, such as circulating tumor plasma cells, extramedullary disease, and functional imaging abnormalities, were not assessed in the MyXI trial, which started in 2011. The incorporation of advanced imaging modalities, such as whole-body MRI could further refine risk prediction by identifying early signs of relapse that escape standard diagnostics.27,28

The strengths of our study include a long follow-up, consistent treatment with a widely accessible standard of care (ASCT followed by Len maintenance), and robust profiling using validated diagnostic platforms. Including only patients with complete genetic profiling data could, in theory, introduce selection bias. However, in the OPTIMUM/MUKnine trial we successfully obtained very similar complete cytogenetic and GEP information in nearly 90 % of all-comer NDMM patients through central screening, with comparable results in terms of frequency of genetic and GEP risk markers,29 rendering clinically significant selection bias in the current study unlikely. Future validation of our results in an external cohort would be desirable but is currently limited by the lack of readily available clinical-trial datasets providing also diagnostic/clinical GEP profiling, uniform treatment, and long-term follow-up. Another limitation is the absence of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody therapy in the MyXI treatment regimen, although recent data suggest that while these agents improve outcomes in HR patients, particularly in those with multiple HRCAs, they do not eliminate the adverse prognosis.30,31 A further constraint is the incomplete data on TP53 mutation status, which were available for only a subset of patients. However, our cohort had complete information on del(17p), and isolated pathogenic TP53 point mutations, especially those that would meet diagnostic NGS reporting threshold, are rare in NDMM. Nevertheless, the finding of a clonal isolated TP53 point mutation in our ER group underpins their potential clinical relevance and supports their inclusion in the updated IMS/IMWG-HR definition.

Finally, although the addition of GEP testing adds to upfront diagnostic expense, the cost of a single, one-off assay is still modest relative to repeated cycles of contemporary standard antimyeloma therapy. Addition of GEP profiling to standard diagnostics has been found to be cost-effective in breast cancer (eg, Oncotype DX) and is reimbursed in public health care systems like the National Health Services. In the context of a growing body of evidence demonstrating differential clinical meaning of MRD test results for SR vs HR patients and its potential impact on treatment decision making, for example with respect to ongoing vs timely limited treatment,32,33 our results suggest that addition of baseline GEP diagnostics for MM can provide marked value for patients and health care systems, by improving the diagnosis of HR as well as of SR patients.

In conclusion, when comprehensive molecular and clinical diagnostics are applied, true FHR MM is uncommon. Our findings advocate for broader access to advanced diagnostic tools in both research routine and clinical practice, to enable more accurate risk stratification and inform treatment planning.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating investigators, centers, and participating patients and their families.

This work was supported by Myeloma UK and infrastructure support from the National Institutes of Health Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR BRC) at The Royal Marsden Hospital and Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom. Primary financial support for National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Myeloma XI was provided by Cancer Research UK (C1298/A10410). S.A.B. was supported by the German Cancer Aid (Department ST43). D.A.C. was supported by Core Clinical Trials Unit Infrastructure from Cancer Research UK (C7852/A25447).

Authorship

Contribution: M.F.K. designed the study; S.A.B. analyzed the data; M.F.K. and S.A.B. wrote the manuscript; and all authors collected and curated data and revised and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.A.C. has received research funding from Celgene Corporation, Amgen, and Merck Sharp and Dohme. C.P. has received consulting fees, honoraria, and travel support from Amgen, Celgene Corporation, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda Oncology. G.C. has received consulting fees and honoraria for Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Amgen, Takeda, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and Oncopeptides; honoraria from Jazz Pharmaceuticals; and research support from Takeda and Celgene. K.B. has received consultancy fees and honoraria from Janssen, Celgene/BMS, Sanofi, and Takeda Oncology. F.E.D. has received honoraria and consulting fees from Celgene/BMS, Takeda, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Amgen, and AbbVie. M.J. has received honoraria from Janssen Oncology, Takeda, and Celgene/BMS; and has consulted for Janssen Oncology, Takeda, AbbVie, Sanofi, and Celgene/BMS. G.J.M. has received consultancy fees, honoraria, and travel support from Amgen, Celgene Corporation, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda Oncology. R.O. has received honoraria from Janssen Oncology, BeiGene, and AstraZeneca; and consulting fees from BeiGene and Janssen Oncology. G.J. has received research funding from Takeda and Celgene/BMS; and honoraria for speaking from Takeda, Celgene/BMS, Amgen, Janssen, Sanofi, and Oncopeptides. M.D. owns stock in Abingdon Health. M.F.K. has received consultancy and honoraria from AbbVie; research funding from BMS; research funding, consultancy, and honoraria from Janssen; and consultancy from Karyopharm, Pfizer, Regeneron, GlaxoSmithKline, and Takeda. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martin F. Kaiser, Division of Genetics and Epidemiology, The Institute of Cancer Research, 123 Old Brompton Rd, London SW7 3RP, United Kingdom; email: martin.kaiser@icr.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

Data are available from the corresponding author, Martin F. Kaiser (martin.kaiser@icr.ac.uk), on request. Only methodologically sound proposals whose proposed use of the data has been approved by the independent trial steering committee will be considered. Following approval, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal