Key Points

Prime editing enables multiplex editing of the γ-globin promoters with high precision in hematopoietic cells.

Multiple edits in the HBG1/2 promoters boost γ-globin beyond individual mutations, offering new therapeutic options for hemoglobinopathies.

Visual Abstract

Fetal hemoglobin reactivation is a promising therapy for β-hemoglobinopathies. We developed a prime editing strategy that introduces multiple mutations in the fetal γ-globin promoters that are expected to increase their activity. We tested multiple targets and optimized a variety of parameters to achieve ∼50% of precise edits in a hematopoietic cell line, with minimal off-target effects. This work improved our understanding of the complex DNA repair mechanisms involved in prime editing. We tested this strategy in patients’ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Although editing efficiency was variable among donors, erythroid clones carrying multiple mutations expressed a significantly higher γ-globin level than cells carrying individual mutations, confirming the potential therapeutic benefit of our combined strategy for patients with β-hemoglobinopathies.

Introduction

β-Hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease (SCD) and β-thalassemias, are caused by mutations affecting adult hemoglobin (Hb) production in erythroid cells. The transplantation of autologous CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease-modified hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) was approved for β-hemoglobinopathies.1 However, alternative strategies are desirable to improve safety and efficacy.

Hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HbF; HPFH) results from point mutations or deletions in the γ-globin (HBG1/2) promoters that either generate activator (KLF1,2 TAL1,3 and GATA14) binding sites (BSs) or disrupt repressor (BCL11A5 and LRF5) BSs (Figure 1A), alleviating disease severity.8 CRISPR/Cas9 reactivates HbF by inducing small insertions and deletions (InDels) that inactivate repressor BSs via DNA double-strand break.9

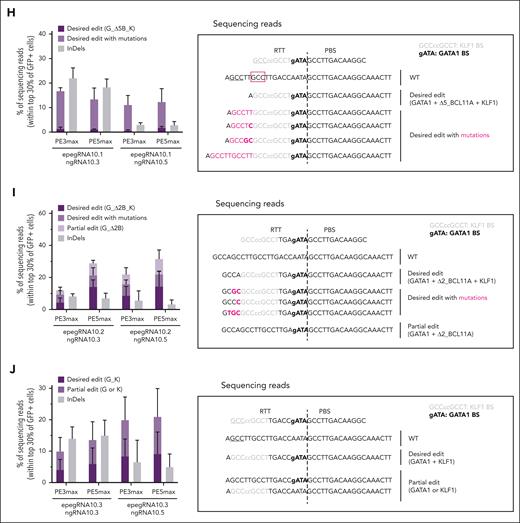

Screening of epegRNAs and ngRNAs targeting the HBG1/2 promoters in K562 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the β-globin locus on chromosome (chr) 11, including the HBG1 and HBG2 genes and their promoters (prom) (top). HPFH or HPFH-like mutations (bold) disrupt LRF or BCL11A repressor BSs (red boxes) or generate KLF1, TAL1, or GATA1 activator (yellow boxes) BSs. PAM-disrupting mutation (PAMm) and BCL11A BS-deletion (Δ2B: ΔCC, Δ5B: ΔTGACC) present in pegRNA1/epegRNA1 and pegRNA10/epegRNA10.1/epegRNA10.2 are displayed below the promoter sequence. Schematic representation of epegRNA5 (bottom left) and epegRNA10.1 (bottom right) targeting the HBG1/2 promoter region. The epegRNA is composed (5′-3′) of a spacer, a scaffold, a primer binding site (PBS), a reverse transcription template (RTT) containing the edits (ie, base substitutions and deletion indicated in colors and black), and the tevopreQ1 motif. Upon annealing of the spacer to the target DNA, the Cas9n induces a DNA single-strand break (ie, nick, arrowhead) liberating the opposite strand (3′ flap), which anneals to the PBS of the epegRNA and primes the reverse transcription of the RTT. The interconversion of the original 5′ flap by the newly synthesized, edited 3′ flap and the degradation of the 5′ flap are essential steps to install the DEs into the target region. (B-C) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (B) pegRNAs or (C) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA1 and ngRNA1.1) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA2 to pegRNA9 and ngRNA5.1 to ngRNA5.9) nucleases. Although pegRNA1 was designed to install KLF1, TAL1, and PAMm mutations (to avoid retargeting of the region), pegRNA2 to pegRNA5 have a shorter RTT to install only the KLF1 BS. (D) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 mutations: PAMm, KLF1, and TAL1 BSs; PAMm_K_T), the partial edits (1 or 2 mutations; K or PAMm_K), or InDels generated using epegRNA1, ngRNA1.1, and PE3max or PE5max in the top 30% green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) cells. (E) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 mutations: KLF1 and TAL1; K_T), the partial edit (1 mutation; K), or InDels generated using epegRNA5, with ngRNA5.5 (left) or ngRNA5.6 (right) and PE3max or PE5max (in their PAM-less SpRY version) in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (F-G) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (F) pegRNAs or (G) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA10 and ngRNA10.1 to ngRNA10.5) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA11 to pegRNA14) nucleases. (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-5-nt BS deletion [ΔTGACC from –114 to –118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ5B_K), DE with mutations, or InDels induced by epegRNA10.1 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.1 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case. The 5 base-pair (5-bp) deletion of the edited 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the closest complementary motif (red square) leading to DE with mutations (pink) with or without scaffold incorporation (pink and bold) (right). (I) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-nt deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), DE with mutations, the partial edit (G_Δ2B) or InDels induced by epegRNA10.2 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.2 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case (right). (J) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 modifications: GATA1 and KLF1 BSs; G_K), the partial edits (GATA1 or KLF1 BSs), or InDels induced by epegRNA10.3 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.3 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions in lower case (right). The long 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the expected complementary motif, preventing the formation of the DE with unintended mutations. (K) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs, the partial edits, or InDels and frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) generated using epegRNA10.2 or epegRNA10.4 with ngRNA10.5 into the HBG1/2 promoters in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (L-M) Top 5 (L) epegRNA10.4- and (M) ngRNA10.5-dependent off-target DNA sites, as identified by GUIDE-seq6 in K562 cells. epegRNA and ngRNA were coupled with a Cas9 nuclease equivalent to the Cas9n included in the PE except for carrying the WT amino acid allowing nuclease activity. The protospacer targeted by each epegRNA or ngRNA and the PAM are reported in the first line, followed by the on- and off-target sites and their mismatches with the on-target (highlighted in color). For each target, the abundance (ie, the total number of unique alignments associated with the target site), chromosomal coordinates (Human GRCh38/hg38), type of region, gene and targeted strand, and number of mismatches with the epegRNA or ngRNA protospacer are reported. In total, we identified 14 off-targets for epegRNA10.4 including only 5 with an abundance >3, and 44 off-targets for ngRNA10.5 including 27 with an abundance >3. Most of them have a high number of mismatches (≥5) and map to nonexonic regions. (B-C,F-G) Samples mock-transfected with Tris-EDTA buffer were used as controls. PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2), and InDels were measured using the TIDE software.7 Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between mock and treated samples (comparison between mock and each of the treated condition) using an unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s Correction) and displayed for ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (D-E,H-K) NGS analysis was performed as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2. A customized Python pipeline was used to align NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and count desired and partial edits, and other InDels. The “Desired edit” and “Partial edits” categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or the ngRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 for the panels D,E,H-J or n = 3 to 4 for the panels K-L biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between the different groups using unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction): data are not significantly different. WT, wild-type.

Screening of epegRNAs and ngRNAs targeting the HBG1/2 promoters in K562 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the β-globin locus on chromosome (chr) 11, including the HBG1 and HBG2 genes and their promoters (prom) (top). HPFH or HPFH-like mutations (bold) disrupt LRF or BCL11A repressor BSs (red boxes) or generate KLF1, TAL1, or GATA1 activator (yellow boxes) BSs. PAM-disrupting mutation (PAMm) and BCL11A BS-deletion (Δ2B: ΔCC, Δ5B: ΔTGACC) present in pegRNA1/epegRNA1 and pegRNA10/epegRNA10.1/epegRNA10.2 are displayed below the promoter sequence. Schematic representation of epegRNA5 (bottom left) and epegRNA10.1 (bottom right) targeting the HBG1/2 promoter region. The epegRNA is composed (5′-3′) of a spacer, a scaffold, a primer binding site (PBS), a reverse transcription template (RTT) containing the edits (ie, base substitutions and deletion indicated in colors and black), and the tevopreQ1 motif. Upon annealing of the spacer to the target DNA, the Cas9n induces a DNA single-strand break (ie, nick, arrowhead) liberating the opposite strand (3′ flap), which anneals to the PBS of the epegRNA and primes the reverse transcription of the RTT. The interconversion of the original 5′ flap by the newly synthesized, edited 3′ flap and the degradation of the 5′ flap are essential steps to install the DEs into the target region. (B-C) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (B) pegRNAs or (C) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA1 and ngRNA1.1) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA2 to pegRNA9 and ngRNA5.1 to ngRNA5.9) nucleases. Although pegRNA1 was designed to install KLF1, TAL1, and PAMm mutations (to avoid retargeting of the region), pegRNA2 to pegRNA5 have a shorter RTT to install only the KLF1 BS. (D) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 mutations: PAMm, KLF1, and TAL1 BSs; PAMm_K_T), the partial edits (1 or 2 mutations; K or PAMm_K), or InDels generated using epegRNA1, ngRNA1.1, and PE3max or PE5max in the top 30% green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) cells. (E) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 mutations: KLF1 and TAL1; K_T), the partial edit (1 mutation; K), or InDels generated using epegRNA5, with ngRNA5.5 (left) or ngRNA5.6 (right) and PE3max or PE5max (in their PAM-less SpRY version) in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (F-G) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (F) pegRNAs or (G) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA10 and ngRNA10.1 to ngRNA10.5) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA11 to pegRNA14) nucleases. (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-5-nt BS deletion [ΔTGACC from –114 to –118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ5B_K), DE with mutations, or InDels induced by epegRNA10.1 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.1 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case. The 5 base-pair (5-bp) deletion of the edited 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the closest complementary motif (red square) leading to DE with mutations (pink) with or without scaffold incorporation (pink and bold) (right). (I) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-nt deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), DE with mutations, the partial edit (G_Δ2B) or InDels induced by epegRNA10.2 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.2 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case (right). (J) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 modifications: GATA1 and KLF1 BSs; G_K), the partial edits (GATA1 or KLF1 BSs), or InDels induced by epegRNA10.3 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.3 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions in lower case (right). The long 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the expected complementary motif, preventing the formation of the DE with unintended mutations. (K) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs, the partial edits, or InDels and frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) generated using epegRNA10.2 or epegRNA10.4 with ngRNA10.5 into the HBG1/2 promoters in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (L-M) Top 5 (L) epegRNA10.4- and (M) ngRNA10.5-dependent off-target DNA sites, as identified by GUIDE-seq6 in K562 cells. epegRNA and ngRNA were coupled with a Cas9 nuclease equivalent to the Cas9n included in the PE except for carrying the WT amino acid allowing nuclease activity. The protospacer targeted by each epegRNA or ngRNA and the PAM are reported in the first line, followed by the on- and off-target sites and their mismatches with the on-target (highlighted in color). For each target, the abundance (ie, the total number of unique alignments associated with the target site), chromosomal coordinates (Human GRCh38/hg38), type of region, gene and targeted strand, and number of mismatches with the epegRNA or ngRNA protospacer are reported. In total, we identified 14 off-targets for epegRNA10.4 including only 5 with an abundance >3, and 44 off-targets for ngRNA10.5 including 27 with an abundance >3. Most of them have a high number of mismatches (≥5) and map to nonexonic regions. (B-C,F-G) Samples mock-transfected with Tris-EDTA buffer were used as controls. PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2), and InDels were measured using the TIDE software.7 Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between mock and treated samples (comparison between mock and each of the treated condition) using an unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s Correction) and displayed for ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (D-E,H-K) NGS analysis was performed as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2. A customized Python pipeline was used to align NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and count desired and partial edits, and other InDels. The “Desired edit” and “Partial edits” categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or the ngRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 for the panels D,E,H-J or n = 3 to 4 for the panels K-L biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between the different groups using unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction): data are not significantly different. WT, wild-type.

Base editors (BEs) allow base transitions, whereas prime editors (PEs) enable base conversions, InDels, and combinations of these mutations,10 thus making them suitable to introduce multiple HPFH mutations, as the coinheritance of these mutations has additive effects on HbF reactivation.11

PEs contain an SpCas9 nickase (Cas9n) fused to a reverse transcriptase (RT). The prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) harbors a scaffold-binding Cas9n, a spacer that drives PE to the target protospacer (where Cas9n induces a single-strand break/nick upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif [PAM]), a primer BS that anneals to the nicked region (serving as a template for the RT), and an RT template (RTT that contains the desired edits [DEs]; Figure 1A). The RTT is reverse transcribed, forming the edited 3′ flap and the unedited 5′ flap is removed (PE2). Editing efficiency is enhanced using a nicking gRNA (ngRNA) that nicks the unedited strand (ie, repaired using the edited strand as template; PE310) and a dominant negative MLH1 that inhibits the mismatch DNA repair pathway (MMR; PE5), which would otherwise reincorporate the original nucleotides.12

Study design

The methods used in this study are described in previous studies6,14 and in the legends of Figures 1-3. Briefly, K562 cells were grown and transfected with plasmids using the Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V and U-16 program (Lonza).6,14 HSPC collection, culture and PE/BE transfection were performed as described in prior studies6,14 and in the legends of Figures 2 and 3. Genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). For K562 Cas9 experiments, InDels were quantified after on-target polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification with recombinant Taq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Sanger sequencing6 (Figure 1 legend). For base and prime editing, on-target DNA was amplified with Phusion High-Fidelity polymerase (New England Biolabs), subjected to NGS as described earlier6 and quantified with a customized Python pipeline or CRISPResso222 (Figures 2 and 3). HBG1/2 4.9-kilobase (kb) deletion was measured by droplet digital PCR.6 Genome-wide, unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) was performed as previously described6 and in the legend to Figure 1. Supplemental Table 2, available on the Blood website lists all primers and probes. Erythroid differentiation; colony-forming assay; the analysis of globins, hemoglobins, erythroid markers, and enucleation; and sickling assay were performed following the previously described methods.6,14

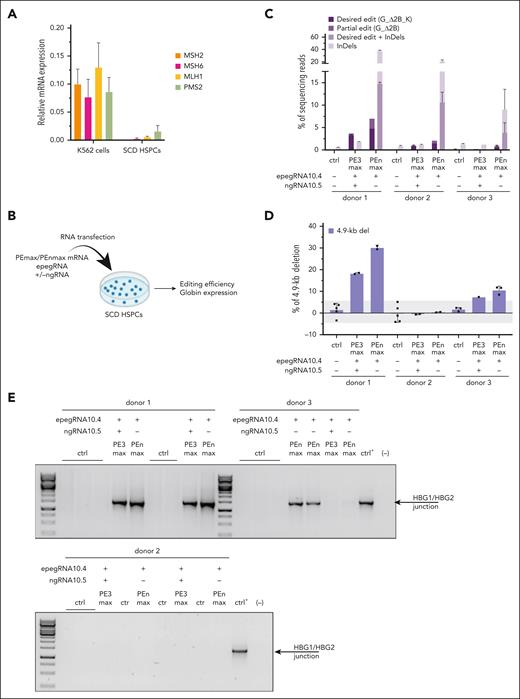

BCL11A BS disruption combined with generation of GATA1 and KLF1 BSs in the HBG1/2 promoters reactivates HbF in erythroid cells differentiated from SCD HSPCs. (A) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of genes encoding the main factors involved in MMR in K562 cells and peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR as previously described.12MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PSM2 mRNA expression was normalized to the expression of ACTB mRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 biologically independent replicates for K562 cells and n = 3 donors for SCD HSPCs. Statistical significance was assessed between K562 and HSPCs for each gene using an unpaired Mann-Whitney test with single comparisons (ie, each comparison stands alone): data are not significantly different. (B) Experimental protocol used for prime editing experiments in peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from donors with SCD. The PEmax or PEnmax mRNA (6.4 μg of mRNA in vitro transcribed as previously described,6 using the AM1334 or AM1345 kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific), epegRNA (200 pmol, Integrated DNA Technologies), with or without the ngRNA (200 pmol, Synthego), and GFP mRNA (0.5 μg, Tebubio), used here as an experimental control for transfection, were cotransfected (P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit [Lonza] and the CA137 program [Nucleofector 4D]) in SCD HSPCs 24 hours after cell thawing and culture in preactivation medium (StemSpan [STEMCELL Technologies] supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin [Thermo Fisher Scientific] and L-glutamine [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 750 μM of StemRegenin1 [STEMCELL Technologies], and the recombinant human cytokines (PeproTech), human stem cell factor (300 ng/mL), Flt-3L [300 ng/mL], thrombopoietin [100 ng/mL], and interleukin-3 [60 ng/mL]). After transfection, bulk HSPCs (ie, without any selection) were either cultured in the preactivation medium or plated in a semisolid medium to induce erythroid differentiation (colony-forming assay). Prime editing efficiency was evaluated in bulk HSPCs 6 days posttransfection and in BFU-Es (pools of 25 colonies and single colonies) by NGS (Illumina, as previously described15 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) and a customized Python pipeline that aligns NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and counts precise and partial edits and InDels (at the pegRNA or ngRNA nick sites). The presence of the 4.9-kb deletion was evaluated by ddPCR and PCR. Globin mRNA expression was quantified in single BFU-E by qRT-PCR and Hb expression in BFU-E pools (25 colonies) by high-performance liquid chromatography, as previously described.14 (C) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. (D) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR generated using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (E) Agarose gel images showing a band corresponding to the PCR product (HBG1/2 junction) obtained as described previously6 using the primers described in supplemental Table 2 surrounding the HBG1/2 junction (generated upon the deletion of the 4.9-kb region) in control (ctrl) SCD HSPCs or SCD HSPCs treated with PEmax or PEnmax (n = 3 donors). For the positive control, we used DNA from K562 cells with 60% of 4.9-kb deletion (ctrl+). For the negative control, we performed the PCR reaction in the absence of DNA (ctrl–). (F) The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.4 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1, GATA1, and BCL11A BSs are indicated in gray, bold, and purple, respectively; the desired base conversions in lower case; and the unexpected deletions with hyphens. Micro-homology motifs involved in deletions are also indicated. InDels included deletions disrupting the BCL11A BS or RTT insertions, both potentially reactivating HbF. (G) Frequency (%) of BFU-E and CFU-GM derived from ctrl– and PE-transfected HSPCs. Results are represented as frequency of colonies obtained from 500 plated HSPCs and shown as mean ± SD. ns, not significant, unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction). (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [CC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. Pools of 25 BFU-E colonies were analyzed for each condition. (I) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (J) HbF and sickle Hb expression measured by high-performance liquid chromatography14 in SCD BFU-E pools treated with epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. (K) γ-Globin mRNA expression (qRT-PCR, normalized on α-globin mRNA as previously described14) in individual BFU-Es derived from SCD HSPCs (1 donor). HSPCs were mock-transfected or transfected with PEn and epegRNA10.4 or BE and gRNAs and cultured in a colony forming cell assay. Each single BFU-E was classified depending on its genotype (determined by NGS). Of note, deviation from expected 25% editing intervals (from 1-4 promoters) indicate that editing occurred over multiple progenitor divisions, as previously reported.6,16 BFU-Es treated with PEn/epgRNA10.4 (n = 53 colonies) carry both DE (G_Δ2B_K) and InDels in variable proportions. For these colonies, we reported on the x-axis either the % of total edits (DE + InDels; red) or only the % of DEs (blue) as a function of γ-globin level for each BFU-E. In the blue group, some colonies have low editing frequency and a high variability of γ-globin level, which can be explained by the presence of InDels that leads to variable, unpredictable γ-globin expression (see InDel group, black line) and by some variability typical of the assay.6,16,17 We also identified a single colony (black arrow) containing 24% of DEs with minimal InDels. This BFU-E expressed the highest γ-globin level, confirming the efficacy of our approach in reactivating γ-globin. In the case of control BFU-Es, we reported mock-transfected colonies (displaying minimal editing due to background NGS errors), colonies containing only InDels obtained from the PEn/epgRNA10.4-treated samples (“InDels”; n = 46 colonies; black; InDels’ frequency were indicated), and colonies containing the GATA1 BS and a disrupted BCL11A BS (A>G at positions –113 and –116 of the HBG promoter, respectively; n = 15 colonies; “+G/–B”; burgundy) or the KLF1 BS (T>C at position –198 of the HBG promoter; n = 16 colonies; “+K”; green), generated using the ABE8-13m18 and published gRNAs.13,17 For BE-treated colonies, we reported the frequency of base conversion (conv.). InDels’ BFU-Es enable to evaluate whether DE in addition to InDels further boost γ-globin expression, whereas +G/–B and +K colonies allow us to compare whether multiple HPFH/HPFH-like mutations (ie, presence of the DE) enhanced γ-globin expression compared to individual mutations. The gray area indicates basal γ-globin expression level (ie, observed in the mock-treated sample). Linear regressions were determined for each category, except the mock. Lines were extended to start at x = 0, and they end exactly at the last data point. The R2 of each linear regression is indicated on the graph. Statistical significance between 2 curves was assessed using linear regression: ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (C-D,G-J) Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 1 to 3 technical replicates per donor (3 donors for C-D and 2 donors for G-J). Tris-EDTA buffer-transfected samples and cells transfected with PEmax or PEnmax and no pegRNA/ngRNA were used as controls (ctrls). (C,H) The DE and partial edit categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or ngRNA.

BCL11A BS disruption combined with generation of GATA1 and KLF1 BSs in the HBG1/2 promoters reactivates HbF in erythroid cells differentiated from SCD HSPCs. (A) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of genes encoding the main factors involved in MMR in K562 cells and peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR as previously described.12MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PSM2 mRNA expression was normalized to the expression of ACTB mRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 biologically independent replicates for K562 cells and n = 3 donors for SCD HSPCs. Statistical significance was assessed between K562 and HSPCs for each gene using an unpaired Mann-Whitney test with single comparisons (ie, each comparison stands alone): data are not significantly different. (B) Experimental protocol used for prime editing experiments in peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from donors with SCD. The PEmax or PEnmax mRNA (6.4 μg of mRNA in vitro transcribed as previously described,6 using the AM1334 or AM1345 kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific), epegRNA (200 pmol, Integrated DNA Technologies), with or without the ngRNA (200 pmol, Synthego), and GFP mRNA (0.5 μg, Tebubio), used here as an experimental control for transfection, were cotransfected (P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit [Lonza] and the CA137 program [Nucleofector 4D]) in SCD HSPCs 24 hours after cell thawing and culture in preactivation medium (StemSpan [STEMCELL Technologies] supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin [Thermo Fisher Scientific] and L-glutamine [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 750 μM of StemRegenin1 [STEMCELL Technologies], and the recombinant human cytokines (PeproTech), human stem cell factor (300 ng/mL), Flt-3L [300 ng/mL], thrombopoietin [100 ng/mL], and interleukin-3 [60 ng/mL]). After transfection, bulk HSPCs (ie, without any selection) were either cultured in the preactivation medium or plated in a semisolid medium to induce erythroid differentiation (colony-forming assay). Prime editing efficiency was evaluated in bulk HSPCs 6 days posttransfection and in BFU-Es (pools of 25 colonies and single colonies) by NGS (Illumina, as previously described15 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) and a customized Python pipeline that aligns NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and counts precise and partial edits and InDels (at the pegRNA or ngRNA nick sites). The presence of the 4.9-kb deletion was evaluated by ddPCR and PCR. Globin mRNA expression was quantified in single BFU-E by qRT-PCR and Hb expression in BFU-E pools (25 colonies) by high-performance liquid chromatography, as previously described.14 (C) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. (D) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR generated using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (E) Agarose gel images showing a band corresponding to the PCR product (HBG1/2 junction) obtained as described previously6 using the primers described in supplemental Table 2 surrounding the HBG1/2 junction (generated upon the deletion of the 4.9-kb region) in control (ctrl) SCD HSPCs or SCD HSPCs treated with PEmax or PEnmax (n = 3 donors). For the positive control, we used DNA from K562 cells with 60% of 4.9-kb deletion (ctrl+). For the negative control, we performed the PCR reaction in the absence of DNA (ctrl–). (F) The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.4 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1, GATA1, and BCL11A BSs are indicated in gray, bold, and purple, respectively; the desired base conversions in lower case; and the unexpected deletions with hyphens. Micro-homology motifs involved in deletions are also indicated. InDels included deletions disrupting the BCL11A BS or RTT insertions, both potentially reactivating HbF. (G) Frequency (%) of BFU-E and CFU-GM derived from ctrl– and PE-transfected HSPCs. Results are represented as frequency of colonies obtained from 500 plated HSPCs and shown as mean ± SD. ns, not significant, unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction). (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [CC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. Pools of 25 BFU-E colonies were analyzed for each condition. (I) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (J) HbF and sickle Hb expression measured by high-performance liquid chromatography14 in SCD BFU-E pools treated with epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. (K) γ-Globin mRNA expression (qRT-PCR, normalized on α-globin mRNA as previously described14) in individual BFU-Es derived from SCD HSPCs (1 donor). HSPCs were mock-transfected or transfected with PEn and epegRNA10.4 or BE and gRNAs and cultured in a colony forming cell assay. Each single BFU-E was classified depending on its genotype (determined by NGS). Of note, deviation from expected 25% editing intervals (from 1-4 promoters) indicate that editing occurred over multiple progenitor divisions, as previously reported.6,16 BFU-Es treated with PEn/epgRNA10.4 (n = 53 colonies) carry both DE (G_Δ2B_K) and InDels in variable proportions. For these colonies, we reported on the x-axis either the % of total edits (DE + InDels; red) or only the % of DEs (blue) as a function of γ-globin level for each BFU-E. In the blue group, some colonies have low editing frequency and a high variability of γ-globin level, which can be explained by the presence of InDels that leads to variable, unpredictable γ-globin expression (see InDel group, black line) and by some variability typical of the assay.6,16,17 We also identified a single colony (black arrow) containing 24% of DEs with minimal InDels. This BFU-E expressed the highest γ-globin level, confirming the efficacy of our approach in reactivating γ-globin. In the case of control BFU-Es, we reported mock-transfected colonies (displaying minimal editing due to background NGS errors), colonies containing only InDels obtained from the PEn/epgRNA10.4-treated samples (“InDels”; n = 46 colonies; black; InDels’ frequency were indicated), and colonies containing the GATA1 BS and a disrupted BCL11A BS (A>G at positions –113 and –116 of the HBG promoter, respectively; n = 15 colonies; “+G/–B”; burgundy) or the KLF1 BS (T>C at position –198 of the HBG promoter; n = 16 colonies; “+K”; green), generated using the ABE8-13m18 and published gRNAs.13,17 For BE-treated colonies, we reported the frequency of base conversion (conv.). InDels’ BFU-Es enable to evaluate whether DE in addition to InDels further boost γ-globin expression, whereas +G/–B and +K colonies allow us to compare whether multiple HPFH/HPFH-like mutations (ie, presence of the DE) enhanced γ-globin expression compared to individual mutations. The gray area indicates basal γ-globin expression level (ie, observed in the mock-treated sample). Linear regressions were determined for each category, except the mock. Lines were extended to start at x = 0, and they end exactly at the last data point. The R2 of each linear regression is indicated on the graph. Statistical significance between 2 curves was assessed using linear regression: ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (C-D,G-J) Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 1 to 3 technical replicates per donor (3 donors for C-D and 2 donors for G-J). Tris-EDTA buffer-transfected samples and cells transfected with PEmax or PEnmax and no pegRNA/ngRNA were used as controls (ctrls). (C,H) The DE and partial edit categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or ngRNA.

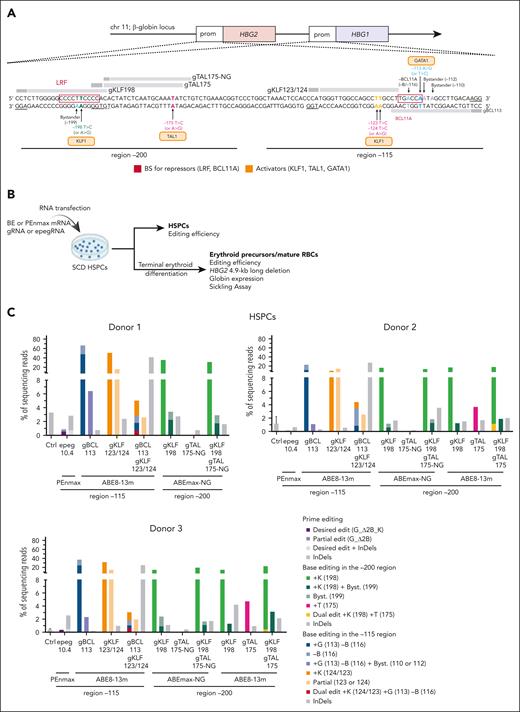

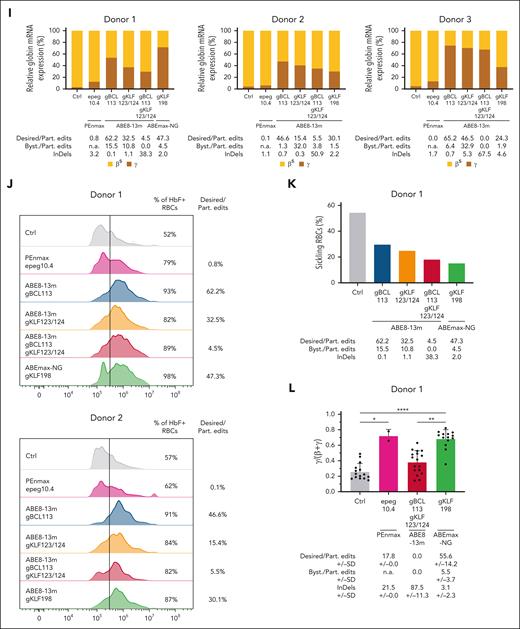

Comparison of prime- and base-editing inducing HPFH/HPFH-like mutations in SCD HSPCs and their erythroid progeny. (A) Schematic representation of the β-globin locus on chromosome (chr) 11 including the HBG1 and HBG2 genes and their promoters (prom). The light and dark gray bars denote the gRNAs used with BEs and their PAM, respectively6,13,17-21 (supplemental Table 1). In the –200 region, gKLF198 induces the T>C (A>G) HPFH mutation at the –198 site generating a KLF1 motif, with a bystander at position –199. gTAL175-NG and gTAL175 generate a TAL1 motif by introducing the HPFH T>C (A>G) mutation at the –175 site, using NG (dotted line) and NGG (solid line) PAMs, respectively. In the –115 region, gKLF123/124 induces T>C (A>G) mutations at the –123 and –124 sites, creating a KLF1 BS. gBCL113 creates an A>G (T>C) mutation at the –113 site, generating GATA1 BS and A>G mutation at the –116 site disrupting the BCL11A BS and bystander edits at the –112 and/or –110 sites. (B) Experimental protocol used for prime and base editing experiments in peripheral blood (donor 1) or bone marrow (donors 2 and 3) CD34+ HSPCs from SCD donors. HSPCs were transfected with PEs using the protocol described in the legend to Figure 2B (supplemental Table 1). For base editing, cells were transfected with 3 μg of in vitro-transcribed BE mRNA (as previously described6) and 1 or 2 guide RNAs (100 pmol each; Integrated DNA Technologies; supplemental Table 1). Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. After transfection, bulk HSPCs (ie, without any selection) were either cultured in preactivation medium or differentiated in mature RBCs following the previously described method6,14 or plated in a semisolid medium to induce erythroid differentiation (colony-forming assay). The editing efficiency was evaluated in bulk HSPCs and erythroid precursors 6 days posttransfection and in single BFU-Es by NGS (Illumina, as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2). The presence of the 4.9-kb deletion was evaluated by ddPCR and PCR as described in the Figure 2 legend. PE and BE efficiency was evaluated following the method described in the Figure 2B legend and the CRISPResso2 webtool,22 respectively. Globin mRNA expression was measured in erythroid precursors and single BFU-Es using qRT-PCR. Hemoglobin, erythroid markers, and enucleation were analyzed by flow cytometry in erythroid precursors and mature RBCs. Sickling assay was performed on mature RBCs. (C-D) Percentage of NGS reads in the HBG promoters in (C) HSPCs and (D) erythroid precursors. Prime editing modifications were reported as indicated in Figure 2C. Base editing was performed using the gRNAs displayed in panel A and ABE8-13m or ABEmax-NG. In the –115 region, +G, –B, and +K refer to GATA1 BS insertion (–113), BCL11A BS (–116) disruption, and KLF1 BS insertion (–124/123), respectively. In the –200 region, +K and +T create the KLF1 (–198) and TAL1 (–175) BSs, respectively. Bystanders (Byst.) were found in positions –110, –112, and –199. Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. (E) NGS reads from the HSPCs of donor 3, ABE8-13m, and gBCL113 generate a new GATA1 motif (blue) and disrupts the BCL11A BS (red). Editing with gKLF123/124 leads to the generation of a KLF1 motif (orange). Multiplex base editing using both gRNAs showed the presence of dual editing events (dual edit) and a high rate of InDels, as shown in the nucleotide distribution around the gRNAs. At each base in the reference amplicon, the percentage of each base as observed in sequencing reads is shown (A = green, C = orange, G = yellow, and T = purple). Black bars show the percentage of reads for which that base was deleted. Brown bars between bases show the percentage of reads having an insertion at that position (top). ABE8-13m and gKLF198 create a KLF1 motif (green). Editing with ABE8-13m and gTAL175 induces the generation of a TAL1 motif (pink). Both gRNAs together allow dual editing (bottom). (F) Frequency (%) of the 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR in HSPCs and erythroid precursors from 3 donors with SCD following editing with PEs or BEs. Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (G) Agarose gel image showing a band corresponding to the PCR product (HBG1/2 junction) obtained using primers surrounding the HBG1/2 junction (generated upon deletion of the 4.9-kb region) in control (ctrl; mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or ABE8-13m mRNA alone) SCD HSPCs or SCD erythroid precursors and treated with PE or BEs (donor 3). For the positive control, we used DNA from K562 cells displaying 60% of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR (ctrl+). For the negative control, we performed the PCR reaction in the absence of DNA (ctrl–). (H) Frequency of CD36+, CD71+, CD235a+, and enucleated RBCs at day 13 (light gray) and 20 (dark gray) of erythroid differentiation, as measured by flow cytometry analysis of CD36, CD71, and CD235a erythroid markers and by DRAQ5 staining for donors 1 and 2. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (I) Globin mRNA expression in erythroid precursors from 3 donors was measured by qRT-PCR. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (J) Flow cytometry histograms showing the frequency of HbF+ cells in erythroid precursors from donors 1 and 2. For each sample, we also reported the editing frequency. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (K) Frequency of sickling RBCs after 2-hour incubation under hypoxic conditions (0% O2) for donor 1. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (L) Globin mRNA expression in single BFU-Es from donor 1 was measured by qRT-PCR. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were transfected only with the PEnmax mRNA. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparison (Dunn’s correction) and displayed as ∗∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗P < .05.

Comparison of prime- and base-editing inducing HPFH/HPFH-like mutations in SCD HSPCs and their erythroid progeny. (A) Schematic representation of the β-globin locus on chromosome (chr) 11 including the HBG1 and HBG2 genes and their promoters (prom). The light and dark gray bars denote the gRNAs used with BEs and their PAM, respectively6,13,17-21 (supplemental Table 1). In the –200 region, gKLF198 induces the T>C (A>G) HPFH mutation at the –198 site generating a KLF1 motif, with a bystander at position –199. gTAL175-NG and gTAL175 generate a TAL1 motif by introducing the HPFH T>C (A>G) mutation at the –175 site, using NG (dotted line) and NGG (solid line) PAMs, respectively. In the –115 region, gKLF123/124 induces T>C (A>G) mutations at the –123 and –124 sites, creating a KLF1 BS. gBCL113 creates an A>G (T>C) mutation at the –113 site, generating GATA1 BS and A>G mutation at the –116 site disrupting the BCL11A BS and bystander edits at the –112 and/or –110 sites. (B) Experimental protocol used for prime and base editing experiments in peripheral blood (donor 1) or bone marrow (donors 2 and 3) CD34+ HSPCs from SCD donors. HSPCs were transfected with PEs using the protocol described in the legend to Figure 2B (supplemental Table 1). For base editing, cells were transfected with 3 μg of in vitro-transcribed BE mRNA (as previously described6) and 1 or 2 guide RNAs (100 pmol each; Integrated DNA Technologies; supplemental Table 1). Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. After transfection, bulk HSPCs (ie, without any selection) were either cultured in preactivation medium or differentiated in mature RBCs following the previously described method6,14 or plated in a semisolid medium to induce erythroid differentiation (colony-forming assay). The editing efficiency was evaluated in bulk HSPCs and erythroid precursors 6 days posttransfection and in single BFU-Es by NGS (Illumina, as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2). The presence of the 4.9-kb deletion was evaluated by ddPCR and PCR as described in the Figure 2 legend. PE and BE efficiency was evaluated following the method described in the Figure 2B legend and the CRISPResso2 webtool,22 respectively. Globin mRNA expression was measured in erythroid precursors and single BFU-Es using qRT-PCR. Hemoglobin, erythroid markers, and enucleation were analyzed by flow cytometry in erythroid precursors and mature RBCs. Sickling assay was performed on mature RBCs. (C-D) Percentage of NGS reads in the HBG promoters in (C) HSPCs and (D) erythroid precursors. Prime editing modifications were reported as indicated in Figure 2C. Base editing was performed using the gRNAs displayed in panel A and ABE8-13m or ABEmax-NG. In the –115 region, +G, –B, and +K refer to GATA1 BS insertion (–113), BCL11A BS (–116) disruption, and KLF1 BS insertion (–124/123), respectively. In the –200 region, +K and +T create the KLF1 (–198) and TAL1 (–175) BSs, respectively. Bystanders (Byst.) were found in positions –110, –112, and –199. Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. (E) NGS reads from the HSPCs of donor 3, ABE8-13m, and gBCL113 generate a new GATA1 motif (blue) and disrupts the BCL11A BS (red). Editing with gKLF123/124 leads to the generation of a KLF1 motif (orange). Multiplex base editing using both gRNAs showed the presence of dual editing events (dual edit) and a high rate of InDels, as shown in the nucleotide distribution around the gRNAs. At each base in the reference amplicon, the percentage of each base as observed in sequencing reads is shown (A = green, C = orange, G = yellow, and T = purple). Black bars show the percentage of reads for which that base was deleted. Brown bars between bases show the percentage of reads having an insertion at that position (top). ABE8-13m and gKLF198 create a KLF1 motif (green). Editing with ABE8-13m and gTAL175 induces the generation of a TAL1 motif (pink). Both gRNAs together allow dual editing (bottom). (F) Frequency (%) of the 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR in HSPCs and erythroid precursors from 3 donors with SCD following editing with PEs or BEs. Control (ctrl) samples were either mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or the ABE8-13m mRNA alone. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (G) Agarose gel image showing a band corresponding to the PCR product (HBG1/2 junction) obtained using primers surrounding the HBG1/2 junction (generated upon deletion of the 4.9-kb region) in control (ctrl; mock-transfected or transfected with the PEnmax or ABE8-13m mRNA alone) SCD HSPCs or SCD erythroid precursors and treated with PE or BEs (donor 3). For the positive control, we used DNA from K562 cells displaying 60% of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR (ctrl+). For the negative control, we performed the PCR reaction in the absence of DNA (ctrl–). (H) Frequency of CD36+, CD71+, CD235a+, and enucleated RBCs at day 13 (light gray) and 20 (dark gray) of erythroid differentiation, as measured by flow cytometry analysis of CD36, CD71, and CD235a erythroid markers and by DRAQ5 staining for donors 1 and 2. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (I) Globin mRNA expression in erythroid precursors from 3 donors was measured by qRT-PCR. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (J) Flow cytometry histograms showing the frequency of HbF+ cells in erythroid precursors from donors 1 and 2. For each sample, we also reported the editing frequency. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (K) Frequency of sickling RBCs after 2-hour incubation under hypoxic conditions (0% O2) for donor 1. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were mock-transfected. (L) Globin mRNA expression in single BFU-Es from donor 1 was measured by qRT-PCR. We reported the editing frequency below each graph. Control (ctrl) samples were transfected only with the PEnmax mRNA. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparison (Dunn’s correction) and displayed as ∗∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗P < .01, and ∗P < .05.

Results and discussion

We designed pegRNAs to generate KLF1 (–198T>C) and TAL1 (–175T>C) BSs into the HBG1/2 promoters (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). These pegRNAs are compatible with PEmax or PEmax-SpRY containing the NGG-PAM Cas9n or the near PAM-less Cas9n-SpRY, respectively.12 Considering that prime editing efficiency correlates with Cas9-induced InDel frequency,23 we screened pegRNAs with Cas9 in K562. We selected pegRNA1 and pegRNA5 showing the highest InDel frequency, along with ngRNA1.1, ngRNA5.5, and ngRNA5.6 (Figure 1B-C; supplemental Table 1). Subsequently, we generated epegRNA1 and epegRNA5, containing a 36-nucleotide (nt) and 30-nt RTT inserting KLF1/TAL1 BSs, respectively (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1), and tevopreQ1, which enhances pegRNA stability.24 epegRNA1 also installs a PAM-disrupting mutation (to avoid retargeting; Figure 1A). These epegRNAs were electroporated with PE3/5max- and green fluorescent protein–expressing plasmids in K562. Although epegRNA1 installed only the KLF1 BS and PAM-disrupting mutation, epegRNA5 generated simultaneously KLF1/TAL1 BSs, albeit at a low frequency (even when using PE5) and with significant InDel generation (that can occur using PEs15,25; Figure 1D-E). These results suggest that the low RT processivity limits the installation of DEs located far from the nick (ie, TAL1 BS) using pegRNA with long RTTs (ie, ≥30 nt). Therefore, we designed pegRNAs with shorter RTTs (ie, 11-14 nt) to insert HPFH mutations, which are both close to the nick, in the –115 region of the HBG1/2 promoters. We simultaneously inserted GATA1 (–113A>G) and KLF1 (–123/–124T>C) BSs and deleted the BCL11A BS (5-nt deletion that also disrupts the PAM: Δ5B, ΔTGACC) (Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). We selected pegRNA10 (13 nt-long RTT), ngRNA10.3, and ngRNA10.5 that showed the highest InDel frequency and added tevopreQ1 to generate epegRNA10.1 (Figure 1A,F-G; supplemental Table 1). In K562, we observed a low DE frequency and DEs with additional mutations (Figure 1H). This finding could be due to the Δ5B that reduces the complementarity of the edited 3′-flap to the opposite strand, facilitating the annealing of the GCC trinucleotide of the 3′-flap to the closest complementary motif. Moreover, some of these unintended mutations contain a partial incorporation of the scaffold that is reverse-transcribed by the RT. ngRNA10.3 caused higher InDel frequencies than ngRNA10.5 (Figure 1H). To increase 3′-flap complementarity, we designed epegRNA10.2 and epegRNA10.3 containing the epegRNA10.1 spacer and primer binding site, as well as a 16- or 18-nt-long RTT inserting the GATA1/KLF1 BSs and deleting or not the BCL11A BS 2-nt core4 (Δ2B:ΔCC; Figure 1A; supplemental Table 1). This modification favored DEs over unintended flap annealing (Figure 1I-J). Scaffold incorporation, which should not affect promoter activity, still occurred with the epegRNA10.2, but always in combination with DEs (Figure 1I). The epegRNA10.2/ngRNA10.5 combination was the most efficient, reaching 34% of total prime editing events (using PE5), with the lowest InDel frequency (Figure 1J). epegRNA10.2 and epegRNA10.3 generated partial edits, suggesting low processivity of the PEmax leading to incomplete reverse transcription of the ≥16-nt-long RTT or exonuclease-mediated 3′-flap resection (Figure 1I-J).

Therefore, we elongated the epegRNA10.2 RTT (+7 nt, epegRNA10.4) to prevent 3′-flap resection and further favor the correct annealing of the edited 3′ flap and increase DE installation (Figure 1K). In K562, epegRNA10.4 led to a 6.4-fold higher editing efficiency than that with epegRNA10.2 (Figure 1K). We also observed the HBG1-HBG2 4.9-kb deletion, likely due to double-strand break generation23 or strand displacement because of the generation of 2 nicks in cis6,15,26 (Figure 1K). Noteworthy, for epegRNA10.4/ngRNA10.5, GUIDE-seq analysis6 revealed few off-targets with ≥3 mismatches, which mapped to nonexonic regions, suggesting that off-target activity, if any, will not dramatically impact gene/protein expression (Figure 1L-M).

Given that MMR genes are poorly expressed in HSPCs12,27 (Figure 2A), we tested epegRNA10.4/ngRNA10.5 in SCD HSPCs using PE3max or Cas9 nuclease-PEmax (PEnmax) that can increase prime editing efficiency28 (Figure 2B). Both PEs inserted DEs in HSPCs with variable efficiencies, as previously reported.27 However, PEnmax outperformed PE3max reaching 7% of DEs/partial edits (Figure 2C). Both systems also generated InDels and 4.9-kb deletions, with a higher frequency for the Cas9 nuclease-based PEnmax (Figure 2C-E). InDels included deletions disrupting the BCL11A BS or RTT insertions, both potentially reactivating HbF (Figure 2F).

We then evaluated whether multiple HPFH/HPFH-like mutations induce high HbF. HSPCs were plated in a medium promoting the growth of erythroid clones (burst-forming unit-erythroid [BFU-E]). PEs did not affect progenitor growth and differentiation (Figure 2G). Editing (including 4.9-kb deletion frequency) was similar between BFU-E and HSPCs, demonstrating no counterselection of edited erythroid cells (Figure 2C-I). PE3max/PEnmax treatment led to HbF reactivation (Figure 2J). Importantly, a clonal analysis showed that the BFU-Es carrying DE and InDels express significantly higher γ-globin levels than colonies carrying only InDels or individual mutations (Figure 2K).

Finally, we compared prime editing with multiplex base editing to insert HPFH mutations using published BEs/gRNAs6,13,17-21 (Figure 3A-B). Editing was substantially lower in PE- than in BE-edited samples (Figure 3C-D). In BE-treated samples, the introduction of individual KLF1 and GATA1 BSs in the –115 region was effective, but their combination led to low dual- and single-editing frequencies and frequent InDels (mainly deletions between the gRNA nicks; Figure 3A-E). In the –200 region, we efficiently generated the KLF1 BS but not the TAL1 BS (even if we tested 2 editors/gRNAs); consequently, dual edits and InDels were rare upon multiplex editing (Figure 3A-E). Furthermore, bystander edits in the –115 site (–110, –112) and –200 (–199) motifs might influence the generation of canonical activator BSs (Figure 3A-E). In addition, 4.9-kb deletions were not detected, even when using PEn, likely because of the low editing (Figure 3F-G).

To evaluate HbF reactivation, we differentiated HSPCs showing relevant base editing efficiencies (ie, harboring the gBCL113 and the gKLF123/124 mutations alone or combined and the gKLF198 mutation) and samples treated with the PEn. Erythroid differentiation was not impacted by the procedure (Figure 3H). Pen led to modest HBG reactivation compared to that with BEs. However, multiplex base editing failed to further increase HBG and HbF expression or correct the sickling phenotype compared to that through individual mutations (Figure 3I-K). Interestingly, prime-edited BFU-E expressed higher or similar HBG levels than dual or single base-edited colonies, even though PE efficiency was substantially lower (Figure 3L).

In conclusion, we provided proof of concept for combining multiple HPFH/HPFH-like mutations to boost HbF expression. Considering that normal erythroid cells have a survival advantage,29 we hypothesized that increasing HbF levels per red blood cell (RBC) could reduce the frequency of edited HSPCs required to achieve therapeutic benefits. Minimizing chimerism requirements for therapeutic action of gene editing by maximizing HbF induction per corrected cell will be critical for in vivo strategies for which editing efficiency is still a limiting factor.30 However, we highlighted the limited efficiency of the prime editing systems for long pegRNAs and hard-to-edit loci.31 The use of PEnmax increased the occurrence of DEs, but further reduction of unwanted events (such as InDels) impairing safety and efficacy of HbF induction is still required (eg, by using DNA-PK inhibitors32). Recent insights also suggest further means of optimizing prime editing efficiency.33,34 Finally, multiplex base editing did not overcome PE limitations, such as InDel generation and the low dual editing efficiency. Overall, these results advance the understanding of the repair mechanisms involved in prime editing and could lead to effective and safe curative treatments for β-hemoglobinopathies across all HBB genotypes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sandra Manceau for collection of the blood samples and the technological core facilities of the Structure Fédérative de Recherche Necker (Inserm Unité de Service 24/CNRS Unité d'Appui et de Recherche 3633) including the flow cytometry platform, Mélanie Parisot for the genomics facility, and Cécile Masson and Mélodie Perrin for the bioinformatics facility.

This work was supported by state funding from the French National Research Agency (Agence Nationale de la Recherche [ANR]; ANR-10-IAHU-01 and ANR-22-CE17-0028 PEMGeT), the European Commission (HORIZON-PathFinder EdiGenT grant 101070903), the AFM-Telethon (PhD fellowship grant 23879; research grants 24331 and 25179), and the European Cooperation in Science and Technology Action Gene Editing for the Treatment of Human Diseases grant CA21113). This study was also supported by the Ecole Universitaire de Recherche Génétique et Epigénétique, reference number ANR-17-EURE-0013 and is part of the Université Paris Cité IdEx number ANR-18-IDEX-0001 funded by the French Government through its “Investments for the Future” program.

Authorship

Contribution: A.C. and M.B.D. designed and conducted experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; L.F. and S.A. conducted experiments and analyzed the data; P.L. conducted experiments and analyzed data; M. Mombled, G.C., and M.A. designed, conducted, and analyzed the GUIDE-seq experiment; C.G. analyzed NGS data and contributed to the design of the experimental strategy; P.A., M.P., and M. Maresca conducted NGS experiments and contributed to the design of the experimental strategy; and A.M. and M.B. conceived the study, designed experiments, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C., A.M., and M.B. are named as inventors on 2 patents describing prime editing approaches for β-hemoglobinopathies (PCT/EP2024/070167 and PCT/EP2024/070163). P.A., M.P., and M. Maresca are employees of AstraZeneca and may be AstraZeneca shareholders. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mégane Brusson, Université Paris Cité, Imagine Institute, Laboratory of Chromatin and Gene Regulation during Development, INSERM UMR1163, 24, Blvd du Montparnasse, 75015 Paris, France; email: megane.brusson@institutimagine.org; and Annarita Miccio, Université Paris Cité, Imagine Institute, Laboratory of Chromatin and Gene Regulation during Development, INSERM UMR1163, 24, Blvd du Montparnasse, 75015 Paris, France; email: annarita.miccio@institutimagine.org.

References

Author notes

A.C. and M.B.D. contributed equally to this work.

L.F. and S.A. contributed equally to this work.

C.G. and M. Maresca contributed equally to this work.

GUIDE-seq data are available in the BioProject repository under the BioProject ID: PRJNA1200278 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1200278).

Data are available from the corresponding authors, Mégane Brusson (megane.brusson@institutimagine.org) and Annarita Miccio (annarita.miccio@institutimagine.org), on request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![Screening of epegRNAs and ngRNAs targeting the HBG1/2 promoters in K562 cells. (A) Schematic representation of the β-globin locus on chromosome (chr) 11, including the HBG1 and HBG2 genes and their promoters (prom) (top). HPFH or HPFH-like mutations (bold) disrupt LRF or BCL11A repressor BSs (red boxes) or generate KLF1, TAL1, or GATA1 activator (yellow boxes) BSs. PAM-disrupting mutation (PAMm) and BCL11A BS-deletion (Δ2B: ΔCC, Δ5B: ΔTGACC) present in pegRNA1/epegRNA1 and pegRNA10/epegRNA10.1/epegRNA10.2 are displayed below the promoter sequence. Schematic representation of epegRNA5 (bottom left) and epegRNA10.1 (bottom right) targeting the HBG1/2 promoter region. The epegRNA is composed (5′-3′) of a spacer, a scaffold, a primer binding site (PBS), a reverse transcription template (RTT) containing the edits (ie, base substitutions and deletion indicated in colors and black), and the tevopreQ1 motif. Upon annealing of the spacer to the target DNA, the Cas9n induces a DNA single-strand break (ie, nick, arrowhead) liberating the opposite strand (3′ flap), which anneals to the PBS of the epegRNA and primes the reverse transcription of the RTT. The interconversion of the original 5′ flap by the newly synthesized, edited 3′ flap and the degradation of the 5′ flap are essential steps to install the DEs into the target region. (B-C) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (B) pegRNAs or (C) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA1 and ngRNA1.1) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA2 to pegRNA9 and ngRNA5.1 to ngRNA5.9) nucleases. Although pegRNA1 was designed to install KLF1, TAL1, and PAMm mutations (to avoid retargeting of the region), pegRNA2 to pegRNA5 have a shorter RTT to install only the KLF1 BS. (D) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 mutations: PAMm, KLF1, and TAL1 BSs; PAMm_K_T), the partial edits (1 or 2 mutations; K or PAMm_K), or InDels generated using epegRNA1, ngRNA1.1, and PE3max or PE5max in the top 30% green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) cells. (E) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 mutations: KLF1 and TAL1; K_T), the partial edit (1 mutation; K), or InDels generated using epegRNA5, with ngRNA5.5 (left) or ngRNA5.6 (right) and PE3max or PE5max (in their PAM-less SpRY version) in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (F-G) Frequency (%) of InDels generated by transfecting plasmids coding for (F) pegRNAs or (G) ngRNAs and Cas9 (pegRNA10 and ngRNA10.1 to ngRNA10.5) or Cas9-SpRY (pegRNA11 to pegRNA14) nucleases. (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-5-nt BS deletion [ΔTGACC from –114 to –118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ5B_K), DE with mutations, or InDels induced by epegRNA10.1 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.1 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case. The 5 base-pair (5-bp) deletion of the edited 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the closest complementary motif (red square) leading to DE with mutations (pink) with or without scaffold incorporation (pink and bold) (right). (I) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-nt deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), DE with mutations, the partial edit (G_Δ2B) or InDels induced by epegRNA10.2 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.2 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions are in lower case (right). (J) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DE (2 modifications: GATA1 and KLF1 BSs; G_K), the partial edits (GATA1 or KLF1 BSs), or InDels induced by epegRNA10.3 with ngRNA10.3 or ngRNA10.5 in the top 30% GFP+ cells (left). The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.3 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1 and GATA1 BSs are indicated in gray and bold, respectively, and the desired base conversions in lower case (right). The long 3′-flap facilitates the annealing of its GCC trinucleotide (underlined) to the expected complementary motif, preventing the formation of the DE with unintended mutations. (K) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs, the partial edits, or InDels and frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) generated using epegRNA10.2 or epegRNA10.4 with ngRNA10.5 into the HBG1/2 promoters in the top 30% GFP+ cells. (L-M) Top 5 (L) epegRNA10.4- and (M) ngRNA10.5-dependent off-target DNA sites, as identified by GUIDE-seq6 in K562 cells. epegRNA and ngRNA were coupled with a Cas9 nuclease equivalent to the Cas9n included in the PE except for carrying the WT amino acid allowing nuclease activity. The protospacer targeted by each epegRNA or ngRNA and the PAM are reported in the first line, followed by the on- and off-target sites and their mismatches with the on-target (highlighted in color). For each target, the abundance (ie, the total number of unique alignments associated with the target site), chromosomal coordinates (Human GRCh38/hg38), type of region, gene and targeted strand, and number of mismatches with the epegRNA or ngRNA protospacer are reported. In total, we identified 14 off-targets for epegRNA10.4 including only 5 with an abundance >3, and 44 off-targets for ngRNA10.5 including 27 with an abundance >3. Most of them have a high number of mismatches (≥5) and map to nonexonic regions. (B-C,F-G) Samples mock-transfected with Tris-EDTA buffer were used as controls. PCR products were subjected to Sanger sequencing (as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2), and InDels were measured using the TIDE software.7 Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between mock and treated samples (comparison between mock and each of the treated condition) using an unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s Correction) and displayed for ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (D-E,H-K) NGS analysis was performed as previously described6 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2. A customized Python pipeline was used to align NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and count desired and partial edits, and other InDels. The “Desired edit” and “Partial edits” categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or the ngRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 for the panels D,E,H-J or n = 3 to 4 for the panels K-L biologically independent replicates. Statistical significance was assessed between the different groups using unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction): data are not significantly different. WT, wild-type.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/146/22/10.1182_blood.2024028166/1/m_blood_bld-2024-028166-gr1km.jpeg?Expires=1767339631&Signature=1vfNl1M1k~ZwJlsCku~vXAB6O9mESf3OsjleST5mtqZSvYDPdRuBNFU9g-CptliNg3bQ47T3WJiQ0jc8J06TNb6K-5M-VC58yH6rhq8LXvLDZx5xMYsXzGFPl8q46~u55I9NFAXua0UKghwQ2OEuozfUiTEvLpksYYQyt7c7jlriZpEcfp4TxoUg1odnwg0OPMv80WbBUAc7pLJQ1yzshhWG3t0Yxqa6PK1D11RQ7f3wYQVZkO4mV9Hud9keWhPeWok0SG79xW1QZX9UmD9JblwHEEGKaRB-Wr3tuVSLiWeXcKHWv~1XMGoHo3tuoHGzSk6V0iY4w0wyorC7MJ9eNw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![BCL11A BS disruption combined with generation of GATA1 and KLF1 BSs in the HBG1/2 promoters reactivates HbF in erythroid cells differentiated from SCD HSPCs. (A) Relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of genes encoding the main factors involved in MMR in K562 cells and peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD, as measured by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR as previously described.12MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PSM2 mRNA expression was normalized to the expression of ACTB mRNA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 3 biologically independent replicates for K562 cells and n = 3 donors for SCD HSPCs. Statistical significance was assessed between K562 and HSPCs for each gene using an unpaired Mann-Whitney test with single comparisons (ie, each comparison stands alone): data are not significantly different. (B) Experimental protocol used for prime editing experiments in peripheral blood CD34+ HSPCs from donors with SCD. The PEmax or PEnmax mRNA (6.4 μg of mRNA in vitro transcribed as previously described,6 using the AM1334 or AM1345 kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific), epegRNA (200 pmol, Integrated DNA Technologies), with or without the ngRNA (200 pmol, Synthego), and GFP mRNA (0.5 μg, Tebubio), used here as an experimental control for transfection, were cotransfected (P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit [Lonza] and the CA137 program [Nucleofector 4D]) in SCD HSPCs 24 hours after cell thawing and culture in preactivation medium (StemSpan [STEMCELL Technologies] supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin [Thermo Fisher Scientific] and L-glutamine [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 750 μM of StemRegenin1 [STEMCELL Technologies], and the recombinant human cytokines (PeproTech), human stem cell factor (300 ng/mL), Flt-3L [300 ng/mL], thrombopoietin [100 ng/mL], and interleukin-3 [60 ng/mL]). After transfection, bulk HSPCs (ie, without any selection) were either cultured in the preactivation medium or plated in a semisolid medium to induce erythroid differentiation (colony-forming assay). Prime editing efficiency was evaluated in bulk HSPCs 6 days posttransfection and in BFU-Es (pools of 25 colonies and single colonies) by NGS (Illumina, as previously described15 using the primers and probes described in supplemental Table 2) and a customized Python pipeline that aligns NGS reads to a reference amplicon sequence and counts precise and partial edits and InDels (at the pegRNA or ngRNA nick sites). The presence of the 4.9-kb deletion was evaluated by ddPCR and PCR. Globin mRNA expression was quantified in single BFU-E by qRT-PCR and Hb expression in BFU-E pools (25 colonies) by high-performance liquid chromatography, as previously described.14 (C) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [ΔCC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. (D) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR generated using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 in HSPCs from 3 donors with SCD. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (E) Agarose gel images showing a band corresponding to the PCR product (HBG1/2 junction) obtained as described previously6 using the primers described in supplemental Table 2 surrounding the HBG1/2 junction (generated upon the deletion of the 4.9-kb region) in control (ctrl) SCD HSPCs or SCD HSPCs treated with PEmax or PEnmax (n = 3 donors). For the positive control, we used DNA from K562 cells with 60% of 4.9-kb deletion (ctrl+). For the negative control, we performed the PCR reaction in the absence of DNA (ctrl–). (F) The sequences of the PBS and RTT of epegRNA10.4 are aligned on the most frequent NGS reads. The KLF1, GATA1, and BCL11A BSs are indicated in gray, bold, and purple, respectively; the desired base conversions in lower case; and the unexpected deletions with hyphens. Micro-homology motifs involved in deletions are also indicated. InDels included deletions disrupting the BCL11A BS or RTT insertions, both potentially reactivating HbF. (G) Frequency (%) of BFU-E and CFU-GM derived from ctrl– and PE-transfected HSPCs. Results are represented as frequency of colonies obtained from 500 plated HSPCs and shown as mean ± SD. ns, not significant, unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test with multiple comparisons (Dunn’s correction). (H) Percentage of NGS reads containing the DEs (3 modifications: GATA1 BS, BCL11A-BS 2-bp deletion [CC –117/–118 upstream of HBG1/2 TSS], and KLF1 BS; G_Δ2B_K), partial edit (G_Δ2B), or InDels in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax. Pools of 25 BFU-E colonies were analyzed for each condition. (I) Frequency (%) of 4.9-kb deletion measured by ddPCR in SCD bulk BFU-Es using epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. The gray area indicates background 4.9-kb deletion levels (ie, observed in the control-treated samples). (J) HbF and sickle Hb expression measured by high-performance liquid chromatography14 in SCD BFU-E pools treated with epegRNA10.4 with or without ngRNA10.5 and PE3max or PEnmax for colonies shown in panel H. (K) γ-Globin mRNA expression (qRT-PCR, normalized on α-globin mRNA as previously described14) in individual BFU-Es derived from SCD HSPCs (1 donor). HSPCs were mock-transfected or transfected with PEn and epegRNA10.4 or BE and gRNAs and cultured in a colony forming cell assay. Each single BFU-E was classified depending on its genotype (determined by NGS). Of note, deviation from expected 25% editing intervals (from 1-4 promoters) indicate that editing occurred over multiple progenitor divisions, as previously reported.6,16 BFU-Es treated with PEn/epgRNA10.4 (n = 53 colonies) carry both DE (G_Δ2B_K) and InDels in variable proportions. For these colonies, we reported on the x-axis either the % of total edits (DE + InDels; red) or only the % of DEs (blue) as a function of γ-globin level for each BFU-E. In the blue group, some colonies have low editing frequency and a high variability of γ-globin level, which can be explained by the presence of InDels that leads to variable, unpredictable γ-globin expression (see InDel group, black line) and by some variability typical of the assay.6,16,17 We also identified a single colony (black arrow) containing 24% of DEs with minimal InDels. This BFU-E expressed the highest γ-globin level, confirming the efficacy of our approach in reactivating γ-globin. In the case of control BFU-Es, we reported mock-transfected colonies (displaying minimal editing due to background NGS errors), colonies containing only InDels obtained from the PEn/epgRNA10.4-treated samples (“InDels”; n = 46 colonies; black; InDels’ frequency were indicated), and colonies containing the GATA1 BS and a disrupted BCL11A BS (A>G at positions –113 and –116 of the HBG promoter, respectively; n = 15 colonies; “+G/–B”; burgundy) or the KLF1 BS (T>C at position –198 of the HBG promoter; n = 16 colonies; “+K”; green), generated using the ABE8-13m18 and published gRNAs.13,17 For BE-treated colonies, we reported the frequency of base conversion (conv.). InDels’ BFU-Es enable to evaluate whether DE in addition to InDels further boost γ-globin expression, whereas +G/–B and +K colonies allow us to compare whether multiple HPFH/HPFH-like mutations (ie, presence of the DE) enhanced γ-globin expression compared to individual mutations. The gray area indicates basal γ-globin expression level (ie, observed in the mock-treated sample). Linear regressions were determined for each category, except the mock. Lines were extended to start at x = 0, and they end exactly at the last data point. The R2 of each linear regression is indicated on the graph. Statistical significance between 2 curves was assessed using linear regression: ∗∗P < .01, ∗P < .05, or not significant. (C-D,G-J) Bars represent the mean ± SD of n = 1 to 3 technical replicates per donor (3 donors for C-D and 2 donors for G-J). Tris-EDTA buffer-transfected samples and cells transfected with PEmax or PEnmax and no pegRNA/ngRNA were used as controls (ctrls). (C,H) The DE and partial edit categories do not contain InDels and are stacked. InDels are located at the nick induced by the epegRNA or ngRNA.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/146/22/10.1182_blood.2024028166/1/m_blood_bld-2024-028166-gr2k.jpeg?Expires=1767339631&Signature=DG1ncg4Q8Mlvav1iyMkmYtdNZDk~bt6VuItFKZWG4AQP1tdmk7-GOJpVwyvCQMlgjIX0Q6fNF5DTe1tEsvvudtcZ8NTOS33H03bjlVCgBMrxRrMEL5nT1Hq54VRIfJC61jaWkqb-kN4wK783GHmSm1KkRgzWwUf5HrXeDyPAFmpKtjCcxSOONOCefFQRxgU8-NNlaBfL9rA180DU8rVyLavW4E0SDpPxAYZ9Jq4WTjiv~yem~EbJHA7hpV1fuVb7rhNZFIUhFnZRQ1y1mjDhPutP~pWJPUeDl58VdDZdR72tBqe2etPC~YVVw~rbiBrApZ2JiZGxmkQOorPzpA0q2g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal